Category: War

Medal of Honor Recipient, Navy Pilot Buried With Full Honors at Arlington National Cemetery

BY:

Medal of Honor awardee Capt. Thomas J. Hudner, Jr., was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery on Wednesday.

Hudner, a Navy pilot, was awarded the nation’s highest military honor for his actions on Dec. 4, 1950, the U.S. Navy said in a statement.

Hudner received the Medal of Honor from President Harry S. Truman for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty” during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War. During a mission, one of his fellow pilots, the Navy’s first African American naval aviator to fly in combat, Ensign Jesse L. Brown, was hit by anti-aircraft fire damaging a fuel line and causing him to crash. After it became clear Brown was seriously injured and unable to free himself, Hudner proceeded to purposefully crash his own aircraft to join Brown and provide aid. Hudner injured his own back during his crash landing, but stayed with Brown until a rescue helicopter arrived. Hudner and the rescue pilot worked in the sub-zero, snow-laden area in an unsuccessful attempt to free Brown from the smoking wreckage. Although the effort to save Brown was not successful, Hudner was recognized for the heroic attempt.

President Harry S. Truman awarded Hudner the Medal of Honor on April 13, 1951, with Brown’s widow, Daisy, present. Hudner and Daisy remained friends for the 50 years following.

Now I know that when most folks here in merica think of Winchester. They think a lot mostly about the Gun that won the West Etc etc.

Strangely enough Winchesters were used in Eastern Europe between The Turks and the Russians under the Czar. Here is what I could find out about the little known episode of the 1866 Winchester.

Now the Russians & the Turks have had a very long and bitter relationship with each other over the years.

Both being of fine fighting stock with some very aggressive leadership. It also helps that both are very religious folks of opposing views , Orthodox Christian versus Islam.)

Then throw in that the Russians have almost always wanted access to the Mediterranean Sea from the Black Sea. Which the Turks own.

So I hope that you can forgive me. As I have lost count of how many times they have had it over the centuries.

Bottom line- The Winchester 1866 was a huge surprise to the Russians in this war. As the amount of lead that it could spit out was a devastating to the attacking Russians.

Here is some more information about this fight.

Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 (Turkish: 93 Harbi (’93 War)) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and the Eastern Orthodox coalition led by the Russian Empire and composed of Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro. Fought in the Balkansand in the Caucasus, it originated in emerging 19th-century Balkan nationalism. Additional factors included Russian hopes of recovering territorial losses suffered during the Crimean War, re-establishing itself in the Black Sea and supporting the political movement attempting to free Balkan nations from the Ottoman Empire.

The Russian-led coalition won the war. As a result, Russia succeeded in claiming several provinces in the Caucasus, namely Kars and Batum, and also annexed the Budjak region. The principalities of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro, each of whom had had de facto sovereignty for some time, formally proclaimed independence from the Ottoman Empire. After almost five centuries of Ottoman domination (1396–1878), the Bulgarian state was re-established as the Principality of Bulgaria, covering the land between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains (except Northern Dobrudja which was given to Romania), as well as the region of Sofia, which became the new state’s capital. The Congress of Berlin in 1878 also allowed Austria-Hungary to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina and Great Britain to take over Cyprus.

Contents

[hide]

Conflict pre-history[edit]

Treatment of Christians in the Ottoman Empire[edit]

Article 9 of the 1856 Paris Peace Treaty, concluded at the end of the Crimean War, obliged the Ottoman Empire to grant Christians equal rights with Muslims. Before the treaty was signed, the Ottoman government issued an edict, the Edict of Gülhane, which proclaimed the principle of the equality of Muslims and non-Muslims,[7] and produced some specific reforms to this end. For example, the jizya tax was abolished and non-Muslims were allowed to join the army.[8]

However, some key aspects of dhimmi status were retained, including that the testimony of Christians against Muslims was not accepted in courts, which granted Muslims effective immunity for offenses conducted against Christians. Although local level relations between communities were often good, this practice encouraged exploitation. Abuses were at their worst in regions with a predominantly Christian population, where local authorities often openly supported abuse as a means to keep Christians subjugated.[9][page needed]

Crisis in Lebanon, 1860[edit]

In 1858, the Maronite peasants, stirred by the clergy, revolted against their Druze feudal overlords and established a peasant republic. In southern Lebanon, where Maronite peasants worked for Druze overlords, Druze peasants sided with their overlords against the Maronites, transforming the conflict into a civil war. Although both sides suffered, about 10,000 Maronites were massacred at the hands of the Druze.[10][11]

Under the threat of European intervention, Ottoman authorities restored order. Nevertheless, French and British intervention followed.[12] Under further European pressure, the Sultan agreed to appoint a Christian governor in Lebanon, whose candidacy was to be submitted by the Sultan and approved by the European powers.[10]

On May 27, 1860 a group of Maronites raided a Druze village.[citation needed] Massacres and reprisal massacres followed, not only in the Lebanon but also in Syria. In the end, between 7,000 and 12,000 people of all religions[citation needed] had been killed, and over 300 villages, 500 churches, 40 monasteries, and 30 schools were destroyed. Christian attacks on Muslims in Beirut stirred the Muslim population of Damascus to attack the Christian minority with between 5,000 and 25,000 of the latter being killed,[citation needed] including the American and Dutch consuls, giving the event an international dimension.

Ottoman foreign minister Mehmed Fuad Pasha came to Syria and solved the problems by seeking out and executing the culprits, including the governor and other officials. Order was restored, and preparations made to give Lebanon new autonomy to avoid European intervention. Nevertheless, in September 1860 France sent a fleet, and Britain joined to prevent a unilateral intervention that could help increase French influence in the area at Britain’s expense.[12]

The revolt in Crete, 1866–1869[edit]

The Moni Arkadiou monastery

The Cretan Revolt, which began in 1866, resulted from the failure of the Ottoman Empire to apply reforms for improving the life of the population and the Cretans’ desire for enosis — union with Greece.[13] The insurgents gained control over the whole island, except for five cities where the Muslims were fortified. The Greek press claimed that Muslims had massacred Greeks and the word was spread throughout Europe. Thousands of Greek volunteers were mobilized and sent to the island.

The siege of Moni Arkadiou monastery became particularly well known. In November 1866, about 250 Cretan Greek combatants and around 600 women and children were besieged by about 23,000 mainly Cretan Muslims aided by Ottoman troops, and this became widely known in Europe. After a bloody battle with a large number of casualties on both sides, the Cretan Greeks finally surrendered when their ammunition ran out but were killed upon surrender.[14]

By early 1869, the insurrection was suppressed, but the Porte offered some concessions, introducing island self-rule and increasing Christian rights on the island. Although the Cretan crisis ended better for the Ottomans than almost any other diplomatic confrontation of the century, the insurrection, and especially the brutality with which it was suppressed, led to greater public attention in Europe to the oppression of Christians in the Ottoman Empire.

Small as the amount of attention is which can be given by the people of England to the affairs of Turkey … enough was transpiring from time to time to produce a vague but a settled and general impression that the Sultans were not fulfilling the “solemn promises” they had made to Europe; that the vices of the Turkish government were ineradicable; and that whenever another crisis might arise affecting the “independence” of the Ottoman Empire, it would be wholly impossible to afford to it again the support we had afforded in the Crimean war.[15]

Changing balance of power in Europe[edit]

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Although on the winning side in the Crimean War, the Ottoman Empire continued to decline in power and prestige. The financial strain on the treasury forced the Ottoman government to take a series of foreign loans at such steep interest rates that, despite all the fiscal reforms that followed, pushed it into unpayable debts and economic difficulties. This was further aggravated by the need to accommodate more than 600,000 Muslim Circassians, expelled by the Russians from the Caucasus, to the Black Sea ports of north Anatolia and the Balkan ports of Constanţa and Varna, which cost a great deal in money and in civil disorder to the Ottoman authorities.[16]

The New European Concert[edit]

The Concert of Europe established in 1814 was shaken in 1859 when France and Austria fought over Italy. It came apart completely as a result of the wars of German Unification, when the Kingdom of Prussia, led by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, defeated Austria in 1866 and France in 1870, replacing Austria-Hungary as the dominant power in Central Europe. Britain, worn out by its participation in the Crimean War and diverted by the Irish question and the social problems created by the Industrial Revolution, chose not to intervene again to restore the European balance. Bismarck did not wish the breakup of the Ottoman Empire to create rivalries that might lead to war, so he took up the Tsar’s earlier suggestion that arrangements be made in case the Ottoman Empire fell apart, creating the Three Emperors’ League with Austria and Russia to keep France isolated on the continent.

France responded by supporting self-determination movements, particularly if they concerned the three emperors and the Sultan. Thus revolts in Poland against Russia and national aspirations in the Balkans were encouraged by France. Russia worked to regain its right to maintain a fleet on the Black Sea and vied with the French in gaining influence in the Balkans by using the new Pan-Slavic idea that all Slavs should be united under Russian leadership. This could be done only by destroying the two empires where most non-Russian Slavs lived, the Habsburg and the Ottoman Empires. The ambitions and the rivalries of the Russians and French in the Balkans surfaced in Serbia, which was experiencing its own national revival and had ambitions that partly conflicted with those of the great powers.[17]

Russia after the Crimean War[edit]

Russia ended the Crimean War with minimal territorial losses, but was forced to destroy its Black Sea Fleet and Sevastopol fortifications. Russian international prestige was damaged, and for many years revenge for the Crimean War became the main goal of Russian foreign policy.

This was not easy however—the Paris Peace Treaty included guarantees of Ottoman territorial integrity by Great Britain, France and Austria; only Prussia remained friendly to Russia.

It was on alliance with Prussia and its chancellor Bismarck that the newly appointed Russian chancellor, Alexander Gorchakov, depended. Russia consistently supported Prussia in her wars with Denmark (1864), Austria (1866)and France (1870). In March 1871, using the crushing French defeat and the support of a grateful Germany, Russia achieved international recognition of its earlier denouncement of Article 11 of the Paris Peace Treaty, thus enabling it to revive the Black Sea Fleet.

Other clauses of the Paris Peace Treaty, however, remained in force, specifically Article 8 with guarantees of Ottoman territorial integrity by Great Britain, France and Austria. Therefore, Russia was extremely cautious in its relations with the Ottoman Empire, coordinating all its actions with other European powers. A Russian war with Turkey would require at least the tacit support of all other Great Powers and Russian diplomacy was waiting for a convenient moment.

Balkan crisis of 1875–1876[edit]

The state of Ottoman administration in the Balkans continued to deteriorate throughout the 19th century, with the central government occasionally losing control over whole provinces. Reforms imposed by European powers did little to improve the conditions of the Christian population, while managing to dissatisfy a sizable portion of the Muslim population. Bosnia and Herzegovina suffered at least two waves of rebellion by the local Muslim population, the most recent in 1850.

Austria consolidated after the turmoil of the first half of the century and sought to reinvigorate its longstanding policy of expansion at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, the nominally autonomous, de facto independent principalities of Serbia and Montenegro also sought to expand into regions inhabited by their compatriots. Nationalist and irredentist sentiments were strong and were encouraged by Russia and her agents. At the same time, a severe drought in Anatolia in 1873 and flooding in 1874 caused famine and widespread discontent in the heart of the Empire. The agricultural shortages precluded the collection of necessary taxes, which forced the Ottoman government to declare bankruptcy in October, 1875 and increase taxes on outlying provinces including the Balkans.

Balkan uprisings[edit]

Herzegovina Uprising[edit]

An uprising against Ottoman rule began in Herzegovina in July 1875. By August almost all of Herzegovina had been seized and the revolt had spread into Bosnia. Supported by nationalist volunteers from Serbia and Montenegro, the uprising continued as the Ottomans committed more and more troops to suppress it.

Bulgarian Uprising[edit]

Bashi-bazouks’ atrocities in Macedonia

The revolt of Bosnia and Herzegovina spurred Bucharest-based Bulgarian revolutionaries into action. In 1875, a Bulgarian uprising was hastily prepared to take advantage of Ottoman preoccupation, but it fizzled before it started. In the spring of 1876, another uprising erupted in the south-central Bulgarian lands despite the fact that there were numerous regular Turkish troops in those areas.

A special Turkish military committee was established to quell the uprising. Regular troops (Nisam) and irregular ones (Redif or Bashi-bazouk) were directed to fight the Bulgarians (May 11 – June 9, 1876). The irregulars were mostly drawn from the Muslim inhabitants of the Bulgarian regions, many of whom were Circassian Islamic population which migrated from the Caucasus or Crimean Tatars who were expelled during the Crimean War and even Islamized Bulgarians. The Turkish army suppressed the revolt, massacring up to 30,000[18][19] people in the process.[20][21] Five thousand out of the seven thousand villagers of Batak were put to death.[22] Both Batak and Perushtitsa, where the majority of the population was also massacred, participated in the rebellion.[19] Many of the perpetrators of those massacres were later decorated by the Ottoman high command.[19]Modern historians have estimated the number of killed Bulgarian population is between 30,000 and 100,000. The Turkish military carried on horribly unjust acts upon the vast Bulgarian populations. [23]

-

Konstantin Makovsky, The martyresses, a painting depicting the atrocities of bashibazouks in Macedonia.

-

Bashibazouks held captive by the Bulgarian and Russian army.

-

Bashi-Bazouks, returning with the spoils from the Romanian shore of the Danube.

International reaction to atrocities in Bulgaria[edit]

Word of the bashi-bazouks’ atrocities filtered to the outside world by way of American-run Robert College located in Constantinople. The majority of the students were Bulgarian, and many received news of the events from their families back home. Soon the Western diplomatic community in Constantinople was abuzz with rumours, which eventually found their way into newspapers in the West. While in Constantinople in 1879, protestant missionary George Warren Woodreported Turkish authorities in Amasia brutally persecuting Christian Armenian refugees from Soukoum Kaleh. He was able to coordinate with British diplomat Edward Malet to bring the matter to the attention of the Sublime Porte, and then to the British foreign secretary Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (the Marquess of Salisbury).[24] In Britain, where Disraeli‘s government was committed to supporting the Ottomans in the ongoing Balkan crisis, the Liberal opposition newspaper Daily News hired American journalist Januarius A. MacGahan to report on the massacre stories firsthand.

MacGahan toured the stricken regions of the Bulgarian uprising, and his report, splashed across the Daily News’s front pages, galvanized British public opinion against Disraeli’s pro-Ottoman policy.[25] In September, opposition leader William Gladstone published his Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East[26] calling upon Britain to withdraw its support for Turkey and proposing that Europe demand independence for Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[27] As the details became known across Europe, many dignitaries, including Charles Darwin, Oscar Wilde, Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi, publicly condemned the Ottoman abuses in Bulgaria.[28]

The strongest reaction came from Russia. Widespread sympathy for the Bulgarian cause led to a nationwide surge in patriotism on a scale comparable with the one during the Patriotic War of 1812. From autumn 1875, the movement to support the Bulgarian uprising involved all classes of Russian society. This was accompanied by sharp public discussions about Russian goals in this conflict: Slavophiles, including Dostoevsky, saw in the impending war the chance to unite all Orthodox nations under Russia’s helm, thus fulfilling what they believed was the historic mission of Russia, while their opponents, westernizers, inspired by Turgenev, denied the importance of religion and believed that Russian goals should not be defense of Orthodoxy but liberation of Bulgaria.[29]

Serbo-Turkish War and diplomatic manoeuvering[edit]

Russia preparing to release the Balkan dogs of war, while Britain warns him to take care. Punch cartoon from June 17, 1876

On June 30, 1876, Serbia, followed by Montenegro, declared war on the Ottoman Empire. In July and August, the ill-prepared and poorly equipped Serbian army helped by Russian volunteers failed to achieve offensive objectives but did manage to repulse the Ottoman offensive into Serbia. Meanwhile, Russia’s Alexander II and Prince Gorchakovmet Austria-Hungary‘s Franz Joseph I and Count Andrássy in the Reichstadt castle in Bohemia. No written agreement was made, but during the discussions, Russia agreed to support Austrian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Austria-Hungary, in exchange, agreed to support the return of Southern Bessarabia—lost by Russia during the Crimean War—and Russian annexation of the port of Batum on the east coast of the Black Sea. Bulgaria was to become autonomous (independent, according to the Russian records).[30]

As the fighting in Bosnia and Herzegovina continued, Serbia suffered a string of setbacks and asked the European powers to mediate an end to the war. A joint ultimatum by the European powers forced the Porte to give Serbia a one-month truce and start peace negotiations. Turkish peace conditions however were refused by European powers as too harsh. In early October, after the truce expired, the Turkish army resumed its offensive and the Serbian position quickly became desperate. On October 31, Russia issued an ultimatum requiring the Ottoman Empire to stop the hostilities and sign a new truce with Serbia within 48 hours. This was supported by the partial mobilization of the Russian army (up to 20 divisions). The Sultan accepted the conditions of the ultimatum.

To resolve the crisis, on December 11, 1876, the Constantinople Conference of the Great Powers was opened in Constantinople (to which the Turks were not invited). A compromise solution was negotiated, granting autonomy to Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina under the joint control of European powers. The Ottomans, however, refused to sacrifice their independence by allowing international representatives to oversee the institution of reforms and sought to discredit the conference by announcing on December 23, the day the conference was closed, that a constitution was adopted that declared equal rights for religious minorities within the Empire. The Ottomans attempted to use this manoeuver to get their objections and amendments to the agreement heard. When they were rejected by the Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire announced its decision to disregard the results of the conference.

On January 15, 1877, Russia and Austria-Hungary signed a written agreement confirming the results of an earlier Reichstadt Agreement in July 1876. This assured Russia of the benevolent neutrality of Austria-Hungary in the impending war. These terms meant that in case of war Russia would do the fighting and Austria would derive most of the advantage. Russia therefore made a final effort for a peaceful settlement. After reaching an agreement with its main Balkan rival and with anti-Ottoman sympathies running high throughout Europe due to the Bulgarian atrocities and the rejection of the Constantinople agreements, Russia finally felt free to declare war.

Course of the war[edit]

Opening manoeuvres[edit]

Dragoons of Nizhny Novgorod pursuing the Turks near Kars, 1877.

Painting by Aleksey Kivshenko.

Russia declared war on the Ottomans on 24 April 1877 and its troops entered Romania through the newly built Eiffel Bridge near Ungheni, on the Prut river.

On April 12, 1877, Romania gave permission to the Russian troops to pass through its territory to attack the Turks, resulting in Turkish bombardments of Romanian towns on the Danube. On May 10, 1877, the Principality of Romania, which was under formal Turkish rule, declared its independence.[31]

At the beginning of the war, the outcome was far from obvious. The Russians could send a larger army into the Balkans: about 300,000 troops were within reach. The Ottomans had about 200,000 troops on the Balkan peninsula, of which about 100,000 were assigned to fortified garrisons, leaving about 100,000 for the army of operation. The Ottomans had the advantage of being fortified, complete command of the Black Sea, and patrol boats along the Danube river.[32] They also possessed superior arms, including new British and American-made rifles and German-made artillery.

Russian crossing of the Danube, June 1877. (Painting by Nikolai Dmitriev-Orenburgsky, 1883.)

In the event, however, the Ottomans usually resorted to passive defense, leaving the strategic initiative to the Russians who, after making some mistakes, found a winning strategy for the war.

The Ottoman military command in Constantinople made poor assumptions of Russian intentions. They decided that Russians would be too lazy to march along the Danube and cross it away from the delta, and would prefer the short way along the Black Sea coast. This would be ignoring the fact that the coast had the strongest, best supplied and garrisoned Turkish fortresses. There was only one well manned fortress along the inner part of the river Danube, Vidin. It was garrisoned only because the troops, led by Osman Pasha, had just taken part in defeating the Serbs in their recent war against the Ottoman Empire.

The Russian campaign was better planned, but it relied heavily on Turkish passivity. A crucial Russian mistake was sending too few troops initially; the Danube was crossed in June by an expeditionary force of about 185,000, which was slightly less than the combined Turkish forces in the Balkans (about 200,000). After setbacks in July (at Pleven and Stara Zagora), the Russian military command realized it did not have the reserves to keep the offensive going and switched to a defensive posture. The Russians did not even have enough forces to blockade Pleven properly until late August, which effectively delayed the whole campaign for about two months.

Balkan theatre[edit]

Russian, Romanian and Ottoman troop movements at Plevna.

At the start of the war, Russia and Romania destroyed all vessels along the Danube and mined the river, thus ensuring that Russian forces could cross the Danube at any point without resistance from the Ottoman navy. The Ottoman command did not appreciate the significance of the Russians’ actions. In June, a small Russian unit crossed the Danube close to the delta, at Galați, and marched towards Ruschuk (today Ruse). This made the Ottomans even more confident that the big Russian force would come right through the middle of the Ottoman stronghold.

Under the direct command of Major-General Mikhail Ivanovich Dragomirov, on the night of 27/28 June 1877 (NS) the Russians constructed a pontoon bridge across the Danube at Svishtov. After a short battle in which the Russians suffered 812 killed and wounded,[33] the Russian secured the opposing bank and drove off the Ottoman infantry brigade defending Svishtov. At this point the Russian force was divided into three parts: the Eastern Detachment under the command of Tsarevich Alexander Alexandrovich, the future Tsar Alexander III of Russia, assigned to capture the fortress of Ruschuk and cover the army’s eastern flank; the Western Detachment, to capture the fortress of Nikopol, Bulgaria and cover the army’s western flank; and the Advance Detachment under Count Joseph Vladimirovich Gourko, which was assigned to quickly move via Veliko Tarnovo and penetrate the Balkan Mountains, the most significant barrier between the Danube and Constantinople.

Responding to the Russian crossing of the Danube, the Ottoman high command in Constantinople ordered Osman Nuri Paşa to advance east from Vidin occupy the fortress of Nikopol, just west of the Russian crossing. On his way to Nikopol, Osman Pasha learned that the Russians had already captured the fortress and so moved to the crossroads town of Plevna (now known as Pleven), which he occupied with a force of approximately 15,000 on 19 July (NS).[34] The Russians, approximately 9,000 under the command of General Schilder-Schuldner, reached Plevna early in the morning. Thus began the Siege of Plevna.

Osman Pasha organized a defense and repelled two Russian attacks with colossal casualties on the Russian side. At that point, the sides were almost equal in numbers and the Russian army was very discouraged.[35] Most analysts agree that a counter-attack would have allowed the Ottomans to gain control of, and destroy, the Russians’ bridge.[who?] However, Osman Pasha had orders to stay fortified in Plevna, and so he did not leave that fortress.

The Ottoman capitulation at Niğbolu (Nicopolis, modern Nikopol) in 1877 was significant, as it was the site of an important Ottoman victory in 1396which marked the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into the Balkans.

Russia had no more troops to throw against Plevna, so the Russians besieged it, and subsequently asked[36]the Romanians to provide extra troops. On August 9, Suleiman Pasha made an attempt to help Osman Pasha with 30,000 troops, but he was stopped by Bulgarians at the Battle of Shipka Pass. After three days of fighting, the volunteers were relieved by a Russian force led by General Radezky, and the Turkish forces withdrew. Soon afterwards, Romanian forces crossed the Danube and joined the siege. On August 16, at Gorni-Studen, the armies (West Army group) around Plevna were placed under the command of the Romanian Prince Carol I, aided by the Russian general Pavel Dmitrievich Zotov and the Romanian general Alexandru Cernat.

The Turks maintained several fortresses around Pleven which the Russian and Romanian forces gradually reduced.[37][38][page needed] The Romanian 4th Division led by General Gheorghe Manutook the Grivitsa redoubt after four bloody assaults and managed to keep it until the very end of the siege. The siege of Plevna (July–December 1877) turned to victory only after Russian and Romanian forces cut off all supply routes to the fortified Ottomans. With supplies running low, Osman Pasha made an attempt to break the Russian siege in the direction of Opanets. On December 9, in the middle of the night the Ottomans threw bridges over the Vit River and crossed it, attacked on a 2-mile (3.2 km) front and broke through the first line of Russian trenches. Here they fought hand to hand and bayonet to bayonet, with little advantage to either side. Outnumbering the Ottomans almost 5 to 1, the Russians drove the Ottomans back across the Vit. Osman Pasha was wounded in the leg by a stray bullet, which killed his horse beneath him. Making a brief stand, the Ottomans eventually found themselves driven back into the city, losing 5,000 men to the Russians’ 2,000. The next day, Osman surrendered the city, the garrison, and his sword to the Romanian colonel, Mihail Cerchez. He was treated honorably, but his troops perished in the snows by the thousand as they straggled off into captivity. The more seriously wounded were left behind in their camp hospitals, only to be murdered by the Bulgarians.[39][dubious ]

At this point Serbia, having finally secured monetary aid from Russia, declared war on the Ottoman Empire again. This time there were far fewer Russian officers in the Serbian army but this was more than offset by the experience gained from the 1876–77 war. Under nominal command of prince Milan Obrenović (effective command was in hands of general Kosta Protić, the army chief of staff), the Serbian Army went on offensive in what is now eastern south Serbia. A planned offensive into the Ottoman Sanjak of Novi Pazar was called off due to strong diplomatic pressure from Austria-Hungary, which wanted to prevent Serbia and Montenegro from coming into contact, and which had designs to spread Austria-Hungary’s influence through the area. The Ottomans, outnumbered unlike two years before, mostly confined themselves to passive defence of fortified positions. By the end of hostilities the Serbs had captured Ak-Palanka (today Bela Palanka), Pirot, Niš and Vranje.

Russians under Field Marshal Joseph Vladimirovich Gourko succeeded in capturing the passes at the Stara Planina mountain, which were crucial for maneuvering. Next, both sides fought a series of battles for Shipka Pass. Gourko made several attacks on the Pass and eventually secured it. Ottoman troops spent much effort to recapture this important route, to use it to reinforce Osman Pasha in Pleven, but failed. Eventually Gourko led a final offensive that crushed the Ottomans around Shipka Pass. The Ottoman offensive against Shipka Pass is considered one of the major mistakes of the war, as other passes were virtually unguarded. At this time a huge number of Ottoman troops stayed fortified along the Black Sea coast and engaged in very few operations.

A Russian army crossed the Stara Planina by a high snowy pass in winter, guided and helped by local Bulgarians, not expected by the Ottoman army, and defeated the Turks at the Battle of Tashkessen and took Sofia. The way was now open for a quick advance through Plovdiv and Edirne to Constantinople.

Besides the Romanian Army (which mobilized 130,000 men, losing 10,000 of them to this war), a strong Finnishcontingent and more than 12,000 volunteer Bulgarian troops (Opalchenie) from the local Bulgarian population as well as many hajduk detachments fought in the war on the side of the Russians. To express his gratitude to the Finnish battalion, the Tsar elevated the battalion on their return home to the name Old Guard Battalion.

Caucasian theatre[edit]

Lagorio, Lev Feliksovich (1891), Russian troops repulsing a Turkish assault against the fortress of Beyazidon June 8, 1877 (oil painting).

Stationed in the Caucasus in Georgia and Armenia was the Russian Caucasus Corps, composed of approximately 50,000 men and 202 guns under the overall command of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, Governor General of the Caucasus.[40] The Russian force stood opposed by an Ottoman Army of 100,000 men led by General Ahmed Muhtar Pasha. While the Russian army was better prepared for the fighting in the region, it lagged behind technologically in certain areas such as heavy artillery and was outgunned, for example, by the superior long-range Krupp artillery that Germany had supplied to the Ottomans.[41]

The Caucasus Corps was led by a quartet of Armenian commanders: Generals Mikhail Loris-Melikov, Arshak Ter-Gukasov (Ter-Ghukasov/Ter-Ghukasyan), Ivan Lazarev and Beybut Shelkovnikov.[42] It was the forces under Lieutenant-General Ter-Gukasov, stationed near Yerevan, that commenced the first assault into Ottoman territory by capturing the town of Bayazid on April 27, 1877.[43]Capitalizing on Ter-Gukasov’s victory there, Russian forces advanced, taking the region of Ardahan on May 17; Russian units also besieged the city of Kars in the final week of May, although Ottoman reinforcements lifted the siege and drove them back. Bolstered by reinforcements, in November 1877 General Lazarev launched a new attack on Kars, suppressing the southern forts leading to the city and capturing Kars itself on November 18.[44] On February 19, 1878 the strategic fortress town of Erzerum was taken by the Russians after a lengthy siege. Although they relinquished control of Erzerum to the Ottomans at the end the war, the Russians acquired the regions of Batum, Ardahan, Kars, Olti, and Sarikamish and reconstituted them into the Kars Oblast.[45]

Civilian government in Bulgaria during the war[edit]

Plevna Chapel near the walls of Kitay-gorod

Liberated by the Imperial Russian Army during the war, Bulgarian territories since April 1877 were under temporary ruling of a provisional Russian administration, which was established at the beginning of the war. The Treaty of Berlin (1878) provided for its termination since the establishment of the Principality of Bulgariaand Eastern Rumelia, in connection with which the provisional Russian administration was abolished in May 1879.[46] The main objectives of the temporary Russian administration was to establish peaceful life and preparation for a revival of the Bulgarian state.

Aftermath[edit]

Intervention by the Great Powers[edit]

Under pressure from the British, Russia accepted the truce offered by the Ottoman Empire on January 31, 1878, but continued to move towards Constantinople.

The British sent a fleet of battleships to intimidate Russia from entering the city, and Russian forces stopped at San Stefano. Eventually Russia entered into a settlement under the Treaty of San Stefano on March 3, by which the Ottoman Empire would recognize the independence of Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, and the autonomy of Bulgaria.

Alarmed by the extension of Russian power into the Balkans, the Great Powers later forced modifications of the treaty in the Congress of Berlin. The main change here was that Bulgaria would be split, according to earlier agreements among the Great Powers that precluded the creation of a large new Slavic state: the northern and eastern parts to become principalities as before (Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia), though with different governors; and the Macedonian region, originally part of Bulgaria under San Stefano, would return to direct Ottoman administration.[47] At the Congress of Berlin, Bismarck said that he was fighting for peace in Europe.

Effects on Bulgaria’s Muslim and Christian population[edit]

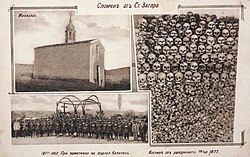

Bones of massacred Bulgarians at Stara Zagora

The estimates of Muslim civilian casualties during the war are often estimated in the tens of thousands.[48] The perpetrators of those massacres are also disputed, with American historian Justin McCarthy, claiming that they were carried out by Russian soldiers, Cossacks as well as Bulgarian volunteers and villagers, though there were few civilian casualties in battle.[49] while James J. Reid claims that Circassians were significantly responsible for the refugee flow, that there were civilian casualties from battle and even that the Ottoman army was responsible for casualties among the Muslim population.[50] According to John Joseph the Russian troops made frequent massacres of Muslim peasants to prevent them from disrupting their supply and troop movements. During the Battle of Harmanliand the accompanying massacre of Muslim civilians, it was reported that a huge group of Muslim refugees were attacked by the Russian army, as a result that thousands of Muslim refugees died and their goods plundered.[51][52] The correspondent of the Daily News describes as an eyewitness the burning of 4 or 5 Turkish villages by the Russian troops in response to the Turks firing at the Russians from the villages, instead of behind rocks or trees.[53]

The number of Muslim refugees is estimated by RJ Crampton as 130,000.[54] Richard C. Frucht estimates that only half (700,000) of the prewar Muslim population remained after the war, 216,000 had died and the rest emigrated.[55] Douglas Arthur Howard estimates that half the 1.5 million Muslims, for the most part Turks, in prewar Bulgaria had disappeared by 1879. 200,000 had died, the rest became permanently refugees in Ottoman territories.[56] However, it should be noted that according to one estimate, the total population of Bulgaria in its postwar borders was about 2.8 million in 1871,[57] while according to official censuses, the total population was 2.823 million in 1880/81.[58]

During the conflict a number of Muslim buildings and cultural centres were destroyed. A large library of old Turkish books was destroyed when a mosque in Turnovo was burned in 1877.[59] Most mosques in Sofia perished, seven of them destroyed in one night in December 1878 when a thunderstorm masked the noise of the explosions arranged by Russian military engineers.”[60]

The Christian population, especially in the initial stages of the war, that found itself in the path of the Ottoman armies also suffered greatly.

The most notable massacre of Bulgarian civilians took part after the July battle of Stara Zagora when Gurko’s forces had to retreat back to the Shipka pass. In the aftermath of the battle Suleiman Pasha‘s forces burned down and plundered the town of Stara Zagora which by that time was one of the largest towns in the Bulgarian lands. The number of massacred Christian civilians during the battle is estimated at 15,000. Suleiman Pasha’s forces also established in the whole valley of the Maritsa river a system of terror taking form in the hanging at the street corners of every Bulgarian who had in any way assisted the Russians, but even villages that had not assisted the Russians were destroyed and their inhabitants massacred.[61] As a result, as many as 100,000 civilian Bulgarians fled north to the Russian occupied territories.[62] Later on in the campaign the Ottoman forces planned to burn the town of Sofia after Gurko had managed to overcome their resistance in the passes of Western part of the Balkan Mountains. Only the refusal of the Italian Consul Vito Positano, the French Vice Consul Léandre François René le Gay and the Austro–Hungarian Vice Consul to leave Sofia prevented that from happening. After the Ottoman retreat, Positano even organized armed detachments to protect the population from marauders (regular Ottoman Army deserters, bashi-bazouks and Circassians).[63]

Bulgarian historians claim that 30,000 civilian Bulgarians were killed during the war, of which two thirds in the Stara Zagora area.[64]

Effects on Bulgaria’s Jewish population[edit]

Many Jewish communities in their entirety were forced to flee with the retreating Turks as their protectors. The Bulletins de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle reported that thousands of Bulgarian Jews found refuge at the Ottoman capital of Constantinople.[65]

Internationalization of the Armenian Question[edit]

The conclusion of the Russo-Turkish war also led to the internationalization of the Armenian Question. Many Armenians in the eastern provinces (Turkish Armenia) of the Ottoman Empire greeted the advancing Russians as liberators. Violence and instability directed at Armenians during the war by Kurd and Circassian bands had left many Armenians looking toward the invading Russians as the ultimate guarantors of their security. In January 1878, Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople Nerses II Varzhapetian approached the Russian leadership with the view of receiving assurances that the Russians would introduce provisions in the prospective peace treaty for self-administration in the Armenian provinces. Though not as explicit, Article 16 of the Treaty of San Stefano read:

As the evacuation of the Russian troops of the territory they occupy in Armenia, and which is to be restored to Turkey, might give rise to conflicts and complications detrimental to the maintenance of good relations between the two countries, the Sublime Porte engaged to carry into effect, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by Armenians and to guarantee their security from Kurds and Circassians.[66]

Great Britain, however, took objection to Russia holding on to so much Ottoman territory and forced it to enter into new negotiations by convening the Congress of Berlin in June 1878. An Armenian delegation led by prelate Mkrtich Khrimiantraveled to Berlin to present the case of the Armenians but, much to its chagrin, was left out of the negotiations. Article 16 was modified and watered down, and all mention of the Russian forces remaining in the provinces was removed. In the final text of the Treaty of Berlin, it was transformed into Article 61, which read:

The Sublime Porte undertakes to carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by Armenians, and to guarantee their security against the Circassians and Kurds. It will periodically make known the steps taken to this effect to the powers, who will superintend their application.[67]

As it turned out, the reforms were not forthcoming. Khrimian returned to Constantinople and delivered a famous speech in which he likened the peace conference to a “‘big cauldron of Liberty Stew’ into which the big nations dipped their ‘iron ladles’ for real results, while the Armenian delegation had only a ‘Paper Ladle’. ‘Ah dear Armenian people,’ Khrimian said, ‘could I have dipped my Paper Ladle in the cauldron it would sog and remain there! Where guns talk and sabers shine, what significance do appeals and petitions have?'”[68] Given the absence of tangible improvements in the plight of the Armenian community, a number of Armenian intellectuals living in Europe and Russia in the 1880s and 1890s formed political parties and revolutionary societies to secure better conditions for their compatriots in Anatolia and other parts of the Ottoman Empire.[69]

Lasting effects[edit]

International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement[edit]

The Red Cross and the Red Crescent emblems

This war caused a division in the emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement which continues to this day. Both Russia and the Ottoman Empire had signed the First Geneva Convention (1864), which made the Red Cross, a color reversal of the flag of neutral Switzerland, the sole emblem of protection for military medical personnel and facilities. However, during this war the cross instead reminded the Ottomans of the Crusades; so they elected to replace the cross with the Red Crescent instead. This ultimately became the symbol of the Movement’s national societies in most Muslimcountries, and was ratified as an emblem of protection by later Geneva Conventions in 1929 and again in 1949 (the current version).

Iran, which neighbored both the Russian Empire and Ottoman Empire, considered them to be rivals, and probably considered the Red Crescent in particular to be an Ottoman symbol; except for the Red Crescent being centered and without a star, it is a color reversal of the Ottoman flag (and the modern Turkish flag). This appears to have led to their national society in the Movement being initially known as the Red Lion and Sun Society, using a red version of the Lion and Sun, a traditional Iranian symbol. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Iran switched to the Red Crescent, but the Geneva Conventions continue to recognize the Red Lion and Sun as an emblem of protection.

In popular culture[edit]

The novel The Doll (Polish title: Lalka), written in 1887–1889 by Bolesław Prus, describes consequences of the Russo-Turkish war for merchants living in Russia and partitioned Poland. The main protagonist helped his Russian friend, a multi-millionaire, and made a fortune supplying the Russian Army in 1877–1878. The novel describes trading during political instability, and its ambiguous results for Russian and Polish societies.

See also[edit]

- Battles of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78)

- Ottoman fleet organisation during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78)

- Batak massacre

- Romanian War of Independence

- Harmanli massacre

- History of the Balkans

- Provisional Russian Administration in Bulgaria

- The Turkish Gambit

- Marche slave

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Timothy C. Dowling. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. 2 Volumes. ABC-CLIO, 2014. P. 748

- Jump up^ Мерников, АГ (2005. – c. 376), Спектор А. А. Всемирная история войн (in Russian), Минск Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Jump up^ Урланис Б. Ц. (1960). “Войны в период домонополистического капитализма (Ч. 2)”. Войны и народонаселение Европы. Людские потери вооруженных сил европейских стран в войнах XVII—XX вв. (Историко-статистическое исследование). М.: Соцэкгиз. pp. 104–105, 129 § 4.

- Jump up^ Scafes, Cornel, et. al., Armata Romania in Razvoiul de Independenta 1877–1878 (The Romanian Army in the War of Independence 1877–1878). Bucuresti, Editura Sigma, 2002, p. 149 (Romence)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Борис Урланис, Войны и народонаселение Европы, Часть II, Глава II http://scepsis.net/library/id_2140.html

- ^ Jump up to:a b Мерников А. Г.; Спектор А. А. (2005). Всемирная история войн. Мн.: Харвест. ISBN 985-13-2607-0.

- Jump up^ Hatt-ı Hümayun (full text), Turkey: Anayasa.

- Jump up^ Vatikiotis, PJ (1997), The Middle East, London: Routledge, p. 217, ISBN 0-415-15849-4.

- Jump up^ Argyll 1879.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Lebanon”, Country Studies, US: Library of Congress, 1994.

- Jump up^ Churchill, C (1862), The Druzes and the Maronites under the Turkish rule from 1840 to 1860, London: B Quaritch, p. 219.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 142–43.

- Jump up^ The Historical Journal, 3 (1): 38–55, 1960 Missing or empty

|title=(help). - Jump up^ Stillman, William James (March 15, 2004), The Autobiography of a Journalist (ebook), II, The Project Gutenberg, eBook#11594.

- Jump up^ Argyll 1879, p. 122.

- Jump up^ Finkel, Caroline (2005), The History of the Ottoman Empire, New York: Basic Books, p. 467.

- Jump up^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 146.

- Jump up^ Hupchick 2002, p. 264.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jonassohn 1999, pp. 209–10.

- Jump up^ Eversley, Baron George Shaw-Lefevre (1924), The Turkish empire from 1288 to 1914, p. 319.

- Jump up^ Jonassohn 1999, p. 210.

- Jump up^ New Statesman, 6: 202 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Jump up^ Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1986), The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804–1920, p. 139.

- Jump up^ Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons and Command, Volume 80. Constantinople: Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. 1880. pp. 70–72. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Jump up^ MacGahan, Januarius A. (1876). Turkish Atrocities in Bulgaria, Letters of the Special Commissioner of the ‘Daily News,’ J.A. MacGahan, Esq., with An Introduction & Mr. Schuyler’s Preliminary Report. London: Bradbury Agnew and Co. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Jump up^ Gladstone 1876.

- Jump up^ Gladstone 1876, p. 64.

- Jump up^ “The liberation of Bulgaria”, History of Bulgaria, US: Bulgarian embassy.

- Jump up^ Хевролина, ВМ, Россия и Болгария: “Вопрос Славянский — Русский Вопрос” (in Russian), RU: Lib FL, archived from the original on October 28, 2007.

- Jump up^ Potemkin, VP, History of world diplomacy 15th century BC – 1940 AD, RU: Diphis.

- Jump up^ Chronology of events from 1856 to 1997 period relating to the Romanian monarchy, Ohio: Kent State University

- Jump up^ Schem, Alexander Jacob (1878), The War in the East: An illustrated history of the Conflict between Russia and Turkey with a Review of the Eastern Question.

- Jump up^ Menning, Bruce (2000), Bayonets before Bullets: The Imperial Russian Army, 1861–1914, Indiana University Press, p. 57.

- Jump up^ von Herbert 1895, p. 131.

- Jump up^ Reminiscences of the King of Roumania, Harper & Brothers, 1899, pp. 274–75.

- Jump up^ Reminiscences of the King of Roumania, Harper & Brothers, 1899, p. 275.

- Jump up^ Furneaux, Rupert (1958), The Siege of Pleven.

- Jump up^ von Herbert 1895.

- Jump up^ Lord Kinross (1977), The Ottoman Centuries, Morrow Quill, p. 522.

- Jump up^ Menning. Bayonets before Bullets, p. 78.

- Jump up^ Allen & Muratoff 1953, pp. 113–14.

- Jump up^ Allen & Muratoff 1953, p. 546.

- Jump up^ “Ռուս-Թուրքական Պատերազմ, 1877–1878”, Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia [The Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878] (in Armenian), 10, Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1984, pp. 93–94.

- Jump up^ Walker, Christopher J (2011), “Kars in the Russo-Turkish Wars of the Nineteenth Century”, in Hovannisian, Richard G, Armenian Kars and Ani, UCLA Armenian History and Culture, Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 10, Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, pp. 217–20.

- ‘Jump up^ Melkonyan, Ashot, “The Kars Oblast, 1878–1918″, Armenian Kars and Ani, pp. 223–44.

- Jump up^ Българските държавни институции 1879–1986. София: ДИ „Д-р Петър Берон“. 1987. pp. 54–55.

- Jump up^ Stavrianos, “Constantinople conference”, The Balkans Since 1453.

- Jump up^ Levene, Mark (2005), Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: The rise of the West and the coming of genocide, p. 225.

- Jump up^ McCarthy, J (2001), The Ottoman Peoples and the end of Empire, Oxford University Press, p. 48.

- Jump up^ Reid 2000, pp. 42–43.

- Jump up^ Medlicott, William Norton, The Congress of Berlin and after, p. 157

- Jump up^ Joseph, John (1983), Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East, p. 84.

- Jump up^ Reid 2000, p. 324.

- Jump up^ Crampton, RJ (1997), A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge University Press, p. 426, ISBN 0-521-56719-X.

- Jump up^ Frucht, Richard C (2005), Eastern Europe, p. 641.

- Jump up^ Howard, Douglas Arthur (2001), The history of Turkey, p. 67

- Jump up^ “Bulgaric”, Europe, Popul stat.

- Jump up^ Crampton, RJ (2007), Bulgaria, p. 424.

- Jump up^ Crampton 2006, p. 111.

- Jump up^ Crampton 2006, p. 114.

- Jump up^ Argyll 1879, p. 49.

- Jump up^ Greene, Francis Vinton (1879). Report on the Russian Army and its Campaigns in Turkey in 1877–1878. D Appleton & Co. p. 204.

- Jump up^ Ivanov, Dmitri (2005-11-08). “Позитано. “Души в окови”” (in Bulgarian). Sega. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Jump up^ Dimitrov, Bozhidar (2002), Russian-Turkish war 1877–1878 (in Bulgarian), p. 75.

- Jump up^ Tamir, V., Bulgaria and Her Jews: A dubious symbiosis, 1979, p. 94–95, Yeshiva University Press

- Jump up^ Hertslet, Edward (1891), The Map of Europe by Treaty, 4, London: Butterworths, p. 2686.

- Jump up^ Hurewitz, Jacob C (1956), Diplomacy in the Near and Middle East: A Documentary Record 1535–1956, I, Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, p. 190.

- Jump up^ Balkian, Peter. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response. New York: HarperCollins, 2003, p. 44.

- Jump up^ Hovannisian, Richard G (1997), “The Armenian Question in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1914”, in Hovannisian, Richard G, The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, New York: St Martin’s Press, pp. 206–12, ISBN 0-312-10168-6.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, William ED; Muratoff, Paul (1953), Caucasian Battlefields, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Argyll, George Douglas Campbell (1879), The Eastern question from the Treaty of Paris 1836 to the Treaty of Berlin 1878 and to the Second Afghan War, 2, London: Strahan.

- Crampton, RJ (2006) [1997], A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-85085-1.

- Gladstone, William Ewart (1876), Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, London: William Clowes & Sons.

- von Herbert, Frederick William (1895), The Defence of Plevna 1877, London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Jonassohn, Kurt (1999), Genocide and gross human rights violations: in comparative perspective.

- Reid, James J (2000), Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839–1878, Stuttgart: Steiner.

- Shaw, Stanford J; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29166-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Acar, Keziban (March 2004). “An examination of Russian Imperialism: Russian Military and intellectual descriptions of the Caucasians during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878”. Nationalities Papers. 32 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1080/0090599042000186151.

- Drury, Ian. The Russo-Turkish War 1877 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012).

- Glenny, Misha (2012), The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–2011, New York: Penguin.

- (in Russian) Kishmishev, Stepan I. (1884), Войнa вь Tурецкой Арменіи, Saint Petersburg: Voen Publication.

- Norman, Charles B. (1878), Armenia, and the Campaign of 1877, London: Cassell Petter & Galpin.

- Yavuz, M Hakan; Sluglett, Peter, eds. (2012), War and Diplomacy: The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and the Treaty of Berlin, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Russo-Turkish War (1877–78). |

- Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, SUC, archived from the original on April 22, 2006.

- Seegel, Steven J, Virtual War, Virtual Journalism?: Russian Media Responses to ‘Balkan’ Entanglements in Historical Perspective, 1877–2001 (PDF), USA: Brown University.

- Military History: Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Digital book index.

- Sowards, Steven W, Twenty Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History, MSU, archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- “Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and the Exploits of Liberators”, Grand war (in Russian), Kulichki.

- The Romanian Army of the Russo-Turkish War 1877–1878, AOL.

- Erastimes (image gallery) (in Bulgarian), 8M, archived from the original on October 13, 2006

- Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). Historical photos.

Video links[edit]

130 years Liberation of Pleven (Plevna)

- Zelenogorsky, Najden (3 March 2007), Mayor of Pleven (video) (speech), Google.

- Stanishev, Sergej (3 March 2007), Bulgarian Prime Minister (video) (speech), Google.

- Potapov (3 March 2007), Ambassador of Russia in Bulgaria (video) (speech), Google.

- Russo-Turkish War (1877–78)

- Conflicts in 1877

- Conflicts in 1878

- Modern history of Bulgaria

- Wars involving Romania

- Wars involving Serbia

- Wars involving Montenegro

- Wars involving Bulgaria

- Russo-Turkish Wars

- 1877 in Bulgaria

- 1878 in Bulgaria

- 1870s in the Ottoman Empire

- Modern history of Armenia

- Modern history of Georgia (country)

Citing a disturbing trend of new soldiers lacking both proper discipline and physical fitness, senior U.S. Army leaders are calling for a tougher and longer basic training program to prepare troops for combat over the next decade.

“We have every reason to get this right, and far fewer reasons not to,” Secretary of the Army Mark Esper said at the Association of the United States Army’s Global Force Symposium in Alabama on Monday. “That’s why we are considering several initiatives — from a new physical fitness regime to reforming and extending basic training — in order to ensure our young men and women are prepared for the rigors of high-intensity combat.”

While Esper didn’t divulge any details of what an extended Basic Combat Training (BCT) might look like, the Army has already floated the idea of adding two weeks to its 10-week program. A redesigned BCT is expected to be implemented by early summer.

The current BCT involves a three-stage process, the first of which is the “Red Phase.” Comprising the first three weeks of training, it’s where recruits begin to learn drills and ceremonies, the seven “Army Core Values, unarmed combat and first aid. Recruits are also introduced to standard-issue weapons like the M-16 assault rifle and M-4 carbine.

In Phase 2, known as the “White Phase,” soldiers begin target practice with their rifles, and become acquainted with other weapons like grenade launchers and machine guns. The recruits also complete a timed obstacle course and learn to work alongside other soldiers.

The final phase, or “Blue Phase,” sees the soldiers complete the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT), learn nighttime combat operations and go on 10- and 15-kilometer field marches. After passing all their tests, the recruits graduate from basic training and move on to Advanced Individual Training, where they focus on specific skills in their field.

“The ultimate goal of the military is to strip a civilian of civilian status and to put them in a military mindset,” Mike Volkin, an Iraq war veteran and author of “The Ultimate Basic Training Guidebook,” told Fox News. “So if you were to boil down the goal of basic training to its essence it would be to conform.”

The new BCT will place an added focus on strict discipline and esprit de corps through a greater emphasis on drills and ceremony, inspections and military history. It will also concentrate heavily on crucial battlefield skills such as marksmanship, physical fitness, first aid and communications.

Along with the new BCT regimen, U.S. Army brass is considering a tougher Combat Readiness Test, which would replace the current three-event APFT with a six-event test Army leaders believe better prepares recruits for the physical challenges of the service’s Warrior Tasks and Battle Drills – the key skills soldiers use to help them survive in combat.

“There’s going to be a much greater emphasis on fitness,” Volkin said. “Throughout the history of basic training, it’s always been about push-ups, sit-ups and the two-mile run, and that’s not a true test of fitness. This six-point test focuses more on core strength and cardio.”

Speaking at the AUSA meeting this week, Esper said that to meet the challenges the U.S. military faces in the next decade – both in combating terrorism and potentially facing off against other large and highly trained militaries – the Army must also reverse its 2017 drawdown. The Army requested 4,000 additional soldiers be added to active forces as part of the 2019 fiscal budget – a move that would swell the ranks to 487,000 active-duty soldiers – with the aim of having half a million active-duty soldiers battle-ready by 2028.

“To meet the challenges of 2028 and beyond, the total Army must grow,” Esper said. “A decade from now, we need an active component above 500,000 soldiers with associated growth in the Guard and Reserve.”

But as the Army looks to expand its ranks, it will also become more selective in who becomes a solider.

Gen. James McConville, the Army’s vice chief of staff, told Military.com that the service is considering revising its screening process to better prepare recruits for basic training and beyond.

Besides screening candidates’ physical fitness before they begin BCT, the Army would screen them again at the start of training to make sure they can meet the physical demands, and is even testing the idea of assigning fitness experts to two divisions.

“We are putting physical therapists, we are putting strength coaches, we are putting dietitians into each of the units, so when the [new] soldiers get there, we continue to keep them in shape as they go forward,” McConville said. “We are going to have to take what we have, we are going to have to develop that talent and we are going to bring them in and make them better.”

Heckler & Koch HK416

| HK416 | |

|---|---|

Norwegian Army Heckler & Koch HK416N with 419 mm (16.5 in) long barrel, an Aimpoint CompM4 red dot sight and a vertical foregrip

|

|

| Type | Assault rifle Carbine Squad automatic weapon(M27 IAR) AR-15 style rifle |

| Place of origin | Germany |

| Service history | |

| In service | 2004–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | War in Afghanistan Iraq War Northern Mali conflict[1] 2013 Lahad Datu standoff[2] |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Heckler & Koch |

| Produced | 2004–present |

| Variants | HK417, M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle, and others |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 2.950 kg (6.50 lb) to 3.855 kg (8.50 lb) |

| Length | 690 mm (27.2 in) to 1,037 mm (40.8 in) (stock extended) |

| Barrel length | 228 mm (9.0 in) to 505 mm (19.9 in) |

| Width | 78 mm (3.1 in) |

| Height | 236 mm (9.3 in) to 240 mm (9.4 in) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | 5.56×45mm NATO |

| Action | Short-stroke piston, rotating bolt |

| Rate of fire | 700–900 rounds/min (cyclic) HK416 850 rounds/min (cyclic) HK416A5[3] |

| Muzzle velocity | Varies according to barrel length: 788 m/s (10.4 in) 882 m/s (14.5 in) 890 m/s (16.5 in) 917 m/s (19.9 in) |

| Effective firing range | 300 m (11″ model) point targets |

| Maximum firing range | 400 m (11″ model) area targets |

| Feed system | 20, 30-round detachable STANAG magazine, 100-round detachable Beta C-Mag |

| Sights | Rear rotary diopter sight and front post, Picatinny rail |

The Heckler & Koch HK416 is an assault rifle/carbine designed and manufactured by Heckler & Koch. Although its design is in large part based on the ArmaLite AR-15 class of weapons, specifically the Colt M4 carbine family issued to the U.S. military, it uses an HK-proprietary short-stroke gas piston systemoriginally derived from the ArmaLiteAR-18 (the same system was also used in Heckler & Koch’s earlier G36family of rifles). The HK416 gained fame as the weapon that United States Navy SEALs from DEVGRU Red Squadron used to kill Osama Bin Laden in 2011.[4][5]

History[edit]

The United States Army‘s Delta Force, at the request of R&D NCO Larry Vickers, collaborated with the German arms maker Heckler & Koch to develop the new carbine in the early 1990s.[when?] During development, Heckler & Koch capitalized on experience gained developing the Bundeswehr‘s Heckler & Koch G36assault rifle, the U.S. Army’s XM8 rifleproject (cancelled in 2005) and the modernization of the British Armed Forces SA80 small arms family.[citation needed] The project was originally called the Heckler & Koch M4, but this was changed in response to a trademark infringement suit filed by Colt Defense.

Delta Force replaced its M4s with the HK416 in 2004, after tests revealed that the piston operating system significantly reduces malfunctions while increasing the life of parts.[6] The HK416 has been tested by the United States military and is in use with some law enforcement agencies and special operations units. It has also been adopted as the standard rifle of the Norwegian Armed Forces and the French Armed Forces.

A modified variant underwent testing by the United States Marine Corps as the M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle. After the Marine Corps Operational Test & Evaluation Activity supervised a round of testing at MCAGCC Twentynine Palms, Fort McCoy, and Camp Shelby (for dust, cold-weather, and hot-weather conditions, respectively). As of March 2012, fielding of 452 IARs has been completed of 4,748 ordered. Five infantry battalions: 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion and 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, out of Camp Pendleton, CA; First Battalion, 3rd Marines, out of Marine Corps Base HI; 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, out of Camp Lejeune, NC; and 1st Battalion, 25th Marines, out of Fort Devens, MA have deployed the weapon.[7][8] In December 2017, the Marine Corps revealed a decision to equip every Marine in an infantry squad with the M27.[9]

Design[edit]

A Norwegian soldier in Afghanistan, armed with the HK416N

The HK416 uses a HK-proprietary short-stroke gas piston system that derives from the HK G36, forgoing the direct impingement gas system standard in AR-15 rifles.[10][11]The HK G36 gas system was in turn partially derived from the AR-18 assault rifle designed in 1963.[12] The HK system uses a short-stroke piston driving an operating rod to force the bolt carrier to the rear. This design prevents combustion gases from entering the weapon’s interior—a shortcoming with direct impingement systems.[13] The reduction in heat and fouling of the bolt carrier group increases the reliability of the weapon and extends the interval between stoppages. During factory tests the HK416 fired 10,000 rounds in full-auto without malfunctioning.[14] It also reduces operator cleaning time and stress on critical components. According to H&K, “experience that Heckler & Koch gained during its highly successful ‘midlife improvement programme’ for the British Army SA80 assault rifle, have now borne fruit in the HK416.”[11]

The HK416 is equipped with a proprietary accessory rail forearm with MIL-STD-1913 rails on all four sides. This lets most current accessories for M4/M16-type weapons fit the HK416. The HK416 rail forearm can be installed and removed without tools by using the bolt locking lug as the screwdriver. The rail forearm is “free-floating” and does not contact the barrel, improving accuracy.

The HK416 has an adjustable multi-position telescopic butt stock, offering six different lengths of pull. The shoulder pad can be either convex or concave and the stock features a storage space for maintenance accessories, spare electrical batteries or other small kit items. It can also be switched out for other variations like Magpul stocks.

The trigger pull is 34 N (7.6 lbf). The empty weight of a HK416 box magazine is 250 g (8.8 oz).

The HK416’s barrel is cold hammer-forged with a 20,000-round service life and features a 6 grooves 178 mm (7 in) right hand twist. The cold hammer-forging process provides a stronger barrel for greater safety in case of an obstructed bore or for extended firing sessions. Modifications for an over-the-beach (OTB) capability such as drainage holes in the bolt carrier and buffer system are available to let the HK416 fire safely after being submerged in water.

Differences from the M4[edit]

The HK416’s outer appearance resembles the M4. It includes international symbols for safe, semi-automatic, and fully automatic. It has a redesigned retractable stock that lets the user rotate the butt plate, and a new pistol grip designed by H&K to more ergonomically fit the hand. A new single-piece hand guard attaches to the rifle with a free floating rail interface system for mounting accessories. The most notable internal difference is the short stroke gas piston system, which is derived from the HK G36.

Furthermore, an adjustable gas block with piston allows reliable operation on short-barrelled models, with or without a suppressor attached. Finally, the HK416 includes a folding front sight, and a rear sight similar to the G3. The HK416 system is offered as an upper receiver, separate from the rest of the rifle, as a replacement to the standard issue M4 upper receiver. It can attach to existing AR-15 family rifles, giving them the new gas system, the new hand guard, and sights, while retaining the original lower receiver. The Heckler & Koch 416 can also be purchased as a fully assembled, stand alone carbine.

Evaluation[edit]

In July 2007, the U.S. Army announced a limited competition between the M4 carbine, FN SCAR, HK416, XCR, and the previously-shelved HK XM8. Ten examples of each of the four competitors were involved. Each weapon fired 6,000 rounds in an extreme dust environment. The shoot-off was for assessing future needs, not to select a replacement for the M4.[15][16] The XM8 scored the best, with only 127 stoppages in 60,000 total rounds, the FN SCAR Light had 226 stoppages, while the HK416 had 233 stoppages. The M4 carbine scored “significantly worse” than the rest of the field with 882 stoppages.[6] However, magazine failures caused 239 of the M4’s 882 failures. Army officials said, in December 2007, that the new magazines could be combat-ready by spring if testing went well.[17][timeframe?]

In December 2009, a modified version of the HK416 was selected for the final testing in the Infantry Automatic Rifle program, designed to partially replace the M249 light machine gunat the squad level for the United States Marine Corps.[18] It beat the three other finalists by FN Herstal and Colt Defense. In July 2010, the HK416 IAR was designated as the M27, and 450 were procured for additional testing.[19]

The Turkish company Makina ve Kimya Endustrisi Kurumu (“Mechanical and Chemical Industry Corporation”) has considered manufacturing a copy of the HK416 as the MKEK Mehmetçik-1 for the Turkish Armed Forces.[20] Instead, the new MPT-76 rifle has been developed by KALEKALIP with MKEK as the producer, with the Mehmetçik-1 dropped from adoption into the Turkish military.[21][22]

The French armed forces conducted a rifle evaluation and trial to replace the FAMAS, and selected the HK416F as its primary firearm in 2016.[23][24] Of the 93,080 rifles, 54,575 will be a “short” version with an 280 mm (11 in) barrel weighing 3.7 kg (8.2 lb) without the ability to use a grenade launcher, and 38,505 will be a “standard” version with a 368 mm (14.5 in) barrel weighing 4 kg (8.8 lb), of which 14,915 will take FÉLIN attachments; standard rifles will be supplied with 10,767 HK269F grenade launchers. 5,000 units are supposed to be delivered in 2017, half of the order delivered by 2022, and the order fulfilled by 2028.[25]The first batch of 400 rifles was delivered on 3 May 2017.[26]

HK416A5[edit]

The HK416 was one of the weapons displayed to U.S. Army officials during an invitation-only Industry Day on November 13, 2008. The goal of the Industry Day was to review current carbine technology prior to writing formal requirements for a future replacement for the M4 carbine.[27][28] The HK416 was then an entry in the Individual Carbine competition to replace the M4. The weapon submitted was known as the HK416A5.[29] It features a stock similar to that of the G28 designated marksman rifle, except slimmer and non-adjustable. The rifle features an improved tool-less adjustable gas regulator for suppressor use, which can accommodate barrel lengths down to 267 mm (10.5 in) without modifications. It also features a redesigned lower receiver with ambidextrous fire controls, optimized magazine and ammunition compatibility, a repair kit housed inside the pistol grip, and a Flat Dark Earth color-scheme.[30] The stock has a fixed buttplate and no longer has a storage space, as well as the sling loops removed from it. The V2 HK Battle grip is incorporated, which has the V2 grip profile with the storage compartment of the V1 grip for tools. The handguard uses a new hexagonal-shaped cross bolt that cannot be removed by the bolt locking lugs, but instead by the takedown tool housed inside the grip.[31] It has a “heavy duty castle nut”, which is more robust than the previous version, therefore making that weak spot more resistant to impact. The Individual Carbine competition was cancelled before a winning weapon was chosen.[32] The HK416A5 offers several additional features compared to the preceding HK416 models and has become the standard military and law enforcement model line.[33]

Variants[edit]

A suppressed D10RS in service with Polish GROM commandos at a media demonstration in May 2011

HKM4[edit]

|

This section does not citeany sources. (March 2017)(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The Heckler & Koch HKM4D was a prototype of the HK416 that bore heavy resemblance to a standard M4 Carbine. The weapon featured the short stroke proprietary piston system later found in the HK416. The rifle came fitted with a polymer two piece handguard, and could also fit the standard M4 Rail Integration System handguard. Two variants, one with a fixed stock and one with a collapsible stock were on display at SHOT Show 2004. These early prototypes lacked the dust cover door found on most rifles of the type.

HK416 based derivates[edit]

- HK416C: The ultra-compact variant, with “C” for Commando. The HK416C has a 228 mm (9.0 in) barrel and is expected to produce muzzle velocities of approximately 730 m/s (2,395 ft/s).[34] The firearm’s precision is specified as ≈ 4 MOA (12 cm at 100 m) by Heckler & Koch.[34][35][36] The HK416C has a high degree of component commonality with the HK416 family, but uses a shortened buffer tube and a collapsible butt-stock similar to variants of H&K’s MP5 sub-machine gun and the HK53 carbine.

- M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle: A squad automatic weapon variant developed from the D16.5RS for the United States Marine Corps.

- HK416A5: Improved carbine entered in the Individual Carbine competition.[30] The competition was cancelled without a weapon chosen.[32]

- HK417: larger caliber variant chambered for 7.62×51mm NATO

Civilian[edit]

Civilian variants of the HK416 and HK417 introduced in 2007 were known as MR223 and MR308 (as they remain known in Europe). Both are semi-automatic rifles with several “sporterized” features. At the 2009 SHOT Show, these two firearms were introduced to the American civilian market renamed respectively MR556 and MR762.[37] There is another variant of the MR556 called the MR556A1, which is an improved version of the former.[38] It was created with input from American special forces units.[39] The MR556A1 lets the upper receiver attach to any M16/M4/AR-15 family lower receiver, as the receiver take-down pins are in the same standard location. The original concept for the MR556 did not allow for this, as the take-down pins were located in a “non-standard” location. The MR223 maintains the “non-standard” location of the pins, disallowing attachment of the upper receiver to the lower receivers of any other M16/M4/AR-15 family of rifles. As of 2012, the MR556A1 upper receiver group fits standard AR-15 lower receivers without modification, and functions reliably with standard STANAG magazines. HK-USA sells a variant under the MR556A1 Competition Model nomenclature; it comes with a 14.5″ free-float Modular Rail System (MRS), 16.5″ barrel, OSS compensator and Magpul CTR buttstock. The firearm’s precision is specified as 1 MOA by Heckler & Koch. In Europe, the MR223A3 variant is sold with the same cosmetic and ergonomical improvements of the HK416A5. The French importer of Heckler & Koch in France, RUAG Defence, have announced that they are going to sell two civilian versions of the HK416F, named the MR223 F-S (14.5″ Standard version) and MR223 F-C (11″ Short version).[40]

Users[edit]

West Point admits Parkland student Peter Wang who died saving classmates

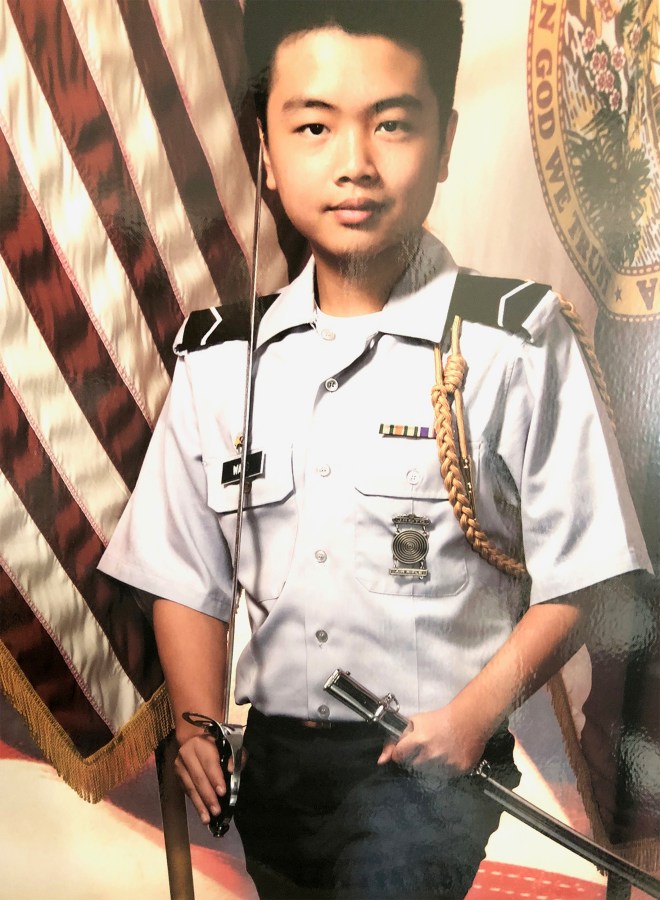

Fifteen-year-old Peter Wang, who was killed while trying to help classmates escape from a gunman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, was posthumously accepted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on Tuesday “for his heroic actions on Feb. 14, 2018” and then buried in his Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC) uniform.

Wang, the U.S. Military Academy said in a statement, “had a lifetime goal to attend USMA.”

Related: These are the 17 victims of the Parkland school shooting

“It was an appropriate way for USMA to honor this brave young man,” it read. “West Point has given posthumous offers of admission in very rare instances for those candidates or potential candidate’s (sic) whose actions exemplified the tenets of Duty, Honor and Country.”

Wang would have been in the Class of 2025, a West Point spokesman said.

The letter was hand-delivered to Wang’s parents by a uniformed Army officer at the funeral home in Coral Springs, Florida, where a gut-wrenching funeral was held as grieving relatives wept beside the slain teenager’s open casket.

When the shooting started at the high school in Parkland, the Brooklyn, N.Y.-born cadet yanked open a door that allowed dozens of classmates, teachers and staffers to escape, officials said.

But as he stood at his post in his JROTC uniform and held the door open, Wang was shot and killed — one of the 17 students and staffers who died in the school that day.

“For as long as we remember him, he is a hero,” classmate Jared Burns told NBC Miami.

“He was like a brother to me and possibly one of the kindest people I ever met,” longtime friend Xi Chen added.

Gov. Rick Scott has directed the Florida National Guard to honor Wang, who was a freshman, and two other JROTC members who were killed — Alaina Petty, 14, and Martin Duque, 14.