Category: Real men

When I first became involved with the U.S. Army’s High Altitude Rescue Team (HART) back in the 1990s, there was a steep learning curve. The mission was to retrieve injured climbers from Mount McKinley and support the National Park Service (NPS) in their mountain operations. At 20,310 feet, Mt. McKinley is the highest point in North America. They call it Denali now. This was quite an unnatural space for a helicopter.

The National Park Service owned the mountain, and they had a contracted civilian helicopter that was based in Talkeetna, Alaska, during the climbing season. This single-engine French Aerospatiale Lama was stripped down to its bare essentials to give it maximum performance at extreme altitudes. When first I crawled aboard this aircraft, I noticed that the copilot’s seat and flight controls had been removed. Needless to say, I was impressed by the bravery required to be a pilot of this helicopter.

For routine trips up the mountain, if ever that was a real thing, the NPS used the Lama. For those times when the Lama was broken, or a bit more horsepower was required, they called us. I can honestly say that flying a helicopter over the top of Mount McKinley was the most extraordinary thing I did as a U.S. Army Aviator.

The Aircraft

For the HART mission, we utilized otherwise unremarkable Boeing CH-47D heavy-lift helicopters. We gutted our Chinooks of any unnecessary kit and fitted them with auxiliary internal fuel tanks and an onboard oxygen system for the crew due to the altitudes in which we would be flying. This labyrinthine thing included plumbing that ran oxygen lines to each crew station to support the flight crew while operating these unpressurized aircraft at extreme altitudes. Our crewmembers also had walkaround bottles that would keep them conscious while moving about the cargo compartment.

The max gross weight for a CH-47D is 50,000 pounds. Its twin Lycoming turboshaft engines put out an aggregate 9,000 shaft horsepower. It is an immensely powerful machine. However, at 21,000 feet the Chinook becomes a big fat pig. Great care had to be taken to plan maneuvers well in advance when the air was that thin. Those sorts of altitudes are terribly unforgiving. However, thusly configured the big Chinook would reliably get us there and back.

The Mission

Denali is actually the tallest mountain on earth, as measured from the base to the summit, even taller than Everest. While the peak of Everest is higher, you don’t have to climb as far to get there. Each year about 1,200 climbers attempt the ascent. Roughly half of them make it. Folks die on that rock all the time. There have been 96 fatalities on the mountain since the first successful ascent in 1913.

The NPS maintains a presence at both the high and low base camps on Denali throughout the approximate three-month climbing season. The low base camp is at 7,200 feet on the Kahiltna glacier. The high base camp is at 14,200 feet.

At the beginning of the climbing season, the HART team is responsible for emplacing the equipment to support these base camps. This consists of tents, food, fuel, radios and the sundry stuff required to keep people alive in such an austere environment. The HART team also retrieves everything at the end. These Army Chinooks also cover the gaps that the small civilian helicopter cannot.

Denali makes its own weather. As many a tourist has discovered to their disappointment, oftentimes the mountain is socked in while the rest of the surrounding area is clear and pretty. As the CH-47 is fully instrument capable, it can sometimes reach the mountain when the Lama cannot. The Chinook is also equipped with a rescue hoist that offers capabilities not available to the smaller machine. In 1988, the HART team set the world record for a helicopter hoist rescue at 18,200 feet. In 1995, the HART team performed a live rescue at 19,600 feet, setting a record for the CH-47 airframe.

War Story

On 3 June 1996, we were on a training mission to get our aircrews qualified for the climbing season. We always ascended the mountain in pairs. The weather had been sketchy and getting to high altitudes had been a challenge.

Two days before, a Spanish climber named Juanjo Garra lost a crampon and fell at the 18,000-foot level at Denali Pass, breaking his leg. At these sorts of altitudes, this is a catastrophic injury. NPS rescue personnel laboriously carried the man to the 14,000-foot base camp, but by then, he was in dire straits.

As we shot a careful approach into the high base camp, we knew nothing of Mr. Garra or his injury. Once we touched down, an Air Force pararescueman who was climbing the mountain as part of a training exercise flashed us with a signal mirror. He explained that Garra had to be removed from the mountain or he could die.

The formal approval process for rescue support was laborious. Each live mission had to be approved by the first General Officer in the chain of command. However, they claimed we Army officers were supposed to show initiative. Mr. Garra was soon strapped in alongside his climbing partner, a Spanish cardiologist. Incidentally, I think that was the closest I have ever come to being kissed by a man. That guy was pretty stoked to be getting off that mountain.

We flew the two Spaniards to the low base camp where they were loaded onboard a ski-equipped airplane for the trip to the Anchorage hospital. I flew home that afternoon assuming I had done a good thing. My boss felt otherwise.

Once we got the aircraft shut down I was dragged into my commander’s office for a proper butt chewing. My on-the-spot decision had completely circumvented the chain of command. I had allowed two foreign nationals onboard a U.S. Army aircraft without proper authorization. The liability had been astronomical. What if the aircraft had crashed? What if there had been an in-flight emergency? What if, what if, what if…

While I was getting reamed out, the phone rang. It was the U.S. Coast Guard congratulating us for the rescue. They wanted the names of the crew for the press release. My boss hung up the phone and sighed. He reluctantly congratulated me for saving a man’s life but then directed me never to do it again.

It has been 27 years since that weird afternoon on Mt. McKinley. I left the Army soon thereafter and went to medical school. Along the way I bought a laptop and tried my hand at writing. Until I was researching this article I had never known Juanjo Garra’s name. I sincerely hope he is well.

——————————————————

A side note from Grumpy

MAY 2013 Spanish mountaineer Juanjo Garra has died on Dhaulagiri (8167m).

This list offers an introduction to the great gun gurus throughout American history. After all, “There’s no nut like a gun nut.”

If you join a gathering of firearm enthusiasts at a hunting camp, shooting range or gun club, rest assured that, if the topic turns to great gun writers, you’ll find opinions as plentiful as scratches in a briar thicket. Everyone has a favorite and will defend that individual with breathless passion and persuasiveness against all comers. You’ll not need to listen long to realize the truth inherent in what a good friend of mine who writes about guns and ammunition once said: “There’s no nut like a gun nut.”

Consider that an acknowledgment that I’m fully aware this list won’t be met with universal approval. All I can offer is that, while I’m no expert on firearms, I’ve done a great deal of reading and study on the subject. That exposure has, over time, given me considerable familiarity with the literature of the field. So, if nothing else, this list offers an introduction to the great gun gurus. However, note that I’ve included only deceased writers, as I don’t need a verbal shooting match with any living expert, self-ordained or otherwise (there are plenty of both). Likewise, for no reason other than the United States has produced most of the finest gun writers, all those listed are Americans.

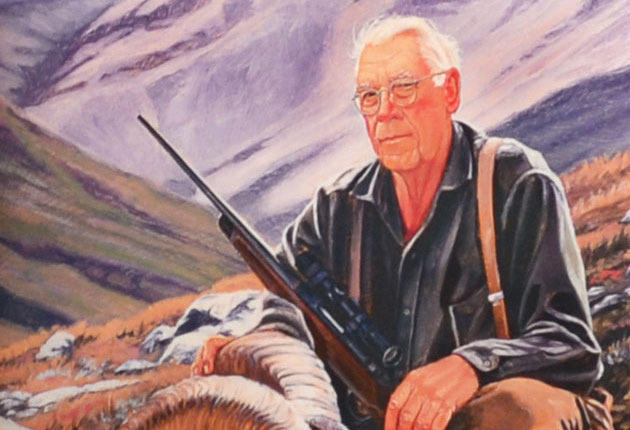

Jack O’Connor

Other writers have had greater technical knowledge, hunted more, and helped develop new calibers and loads, but, when it comes to writing for the average shooter, O’Connor ranks first. Literate, a masterful storyteller, and unabashedly independent (he never sold his soul to any gunmaker or ammunition company, though he had his favorites), he remains immensely enjoyable. The Rifle Book is the place to start, followed by The Shotgun Book. You can find a full bibliography of his writings in The Lost Classics of Jack O’Connor, which I edited.

Other writers have had greater technical knowledge, hunted more, and helped develop new calibers and loads, but, when it comes to writing for the average shooter, O’Connor ranks first. Literate, a masterful storyteller, and unabashedly independent (he never sold his soul to any gunmaker or ammunition company, though he had his favorites), he remains immensely enjoyable. The Rifle Book is the place to start, followed by The Shotgun Book. You can find a full bibliography of his writings in The Lost Classics of Jack O’Connor, which I edited.

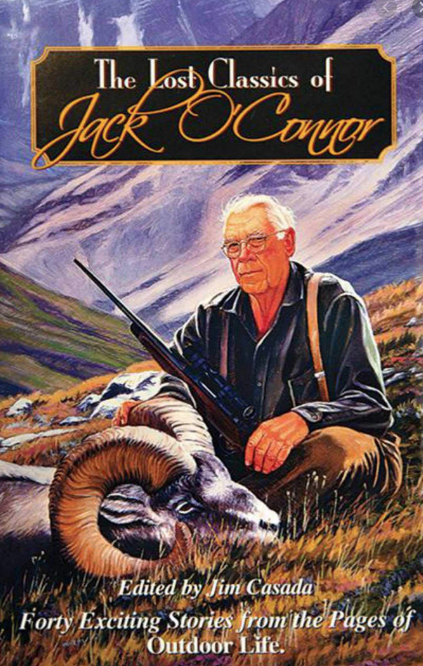

Elmer Keith

Keith both despised and was the antithesis of O’Connor. He liked guns that had punch and produced lots of noise and recoil. While only marginally literate, he told gripping tales; shot a lot; and, with the help of excellent editors, garnered a huge following. The title of his autobiography, Hell, I Was There!, offers a window into his personality, while Sixguns and Big Game Rifles and Cartridges also merit attention. The little man in the big cowboy hat could be obstinate and ornery, but there’s no denying that he could entertain.

Keith both despised and was the antithesis of O’Connor. He liked guns that had punch and produced lots of noise and recoil. While only marginally literate, he told gripping tales; shot a lot; and, with the help of excellent editors, garnered a huge following. The title of his autobiography, Hell, I Was There!, offers a window into his personality, while Sixguns and Big Game Rifles and Cartridges also merit attention. The little man in the big cowboy hat could be obstinate and ornery, but there’s no denying that he could entertain.

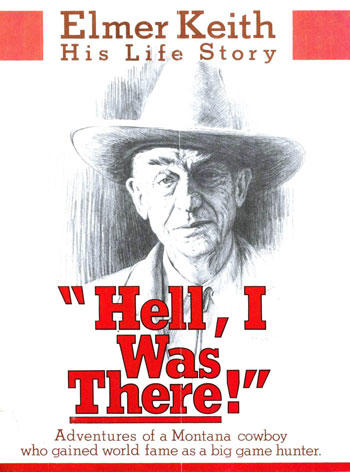

Warren Page

Likeable in print and the ultimate curmudgeon in person (the latter is by no means unique to Page among gun writers), he served as the shooting editor for Field & Stream for a quarter of a century, beginning in 1947, and helped develop the .243 Winchester. His two key books, One Man’s Wilderness and The Accurate Rifle, should be more widely read than they are today.

Likeable in print and the ultimate curmudgeon in person (the latter is by no means unique to Page among gun writers), he served as the shooting editor for Field & Stream for a quarter of a century, beginning in 1947, and helped develop the .243 Winchester. His two key books, One Man’s Wilderness and The Accurate Rifle, should be more widely read than they are today.

Townsend Whelen

If you asked me which of the old-time gun writers I’d most like to have spent time with, “Townie” Whelen would win, hands down. He was the master of practicality, and every avid outdoorsman should read his On Your Own in The Wilderness (with Bradford Angier) and Mister Rifleman, an autobiographical work that Angier also helped complete. Whelen’s other books of note include The American Rifle, Big Game Hunting, Why Not Load Your Own!, The Best of Colonel Townsend Whelen, The Ultimate in Rifle Precision, and Amateur Gunsmithing. Perhaps no quotation by a gun writer has been repeated more frequently than his suggestion that “only accurate rifles are interesting.”

If you asked me which of the old-time gun writers I’d most like to have spent time with, “Townie” Whelen would win, hands down. He was the master of practicality, and every avid outdoorsman should read his On Your Own in The Wilderness (with Bradford Angier) and Mister Rifleman, an autobiographical work that Angier also helped complete. Whelen’s other books of note include The American Rifle, Big Game Hunting, Why Not Load Your Own!, The Best of Colonel Townsend Whelen, The Ultimate in Rifle Precision, and Amateur Gunsmithing. Perhaps no quotation by a gun writer has been repeated more frequently than his suggestion that “only accurate rifles are interesting.”

Paul Curtis

This name will likely be unfamiliar to many sportsmen, but, in the golden era of gun and hunting writers, Curtis was one of the best. For two decades, from the end of World War I until he committed suicide (an all-too-common occurrence among gun writers), Curtis was a major presence in national magazines. He wrote five books, but Guns and Gunning and Sporting Firearms of Today in Use are of the greatest interest.

This name will likely be unfamiliar to many sportsmen, but, in the golden era of gun and hunting writers, Curtis was one of the best. For two decades, from the end of World War I until he committed suicide (an all-too-common occurrence among gun writers), Curtis was a major presence in national magazines. He wrote five books, but Guns and Gunning and Sporting Firearms of Today in Use are of the greatest interest.

Charles Askins, Jr.

Since Charles Askins, Sr. was a gun writer, as well, the two Askins are easily and often confused. However, the younger was more prolific than his father, though the latter wrote a first-rate book about shotguns. The best place to start with Askins, Jr. is Unrepentant Sinner, his autobiography. By all accounts he was a highly temperamental man, involved in shenanigans that would result in hard time today, but there’s no doubting his expertise in works such as The Art of Handgun Shooting, The Gunfighters, and The African Hunt.

Since Charles Askins, Sr. was a gun writer, as well, the two Askins are easily and often confused. However, the younger was more prolific than his father, though the latter wrote a first-rate book about shotguns. The best place to start with Askins, Jr. is Unrepentant Sinner, his autobiography. By all accounts he was a highly temperamental man, involved in shenanigans that would result in hard time today, but there’s no doubting his expertise in works such as The Art of Handgun Shooting, The Gunfighters, and The African Hunt.

William H. “Bill” Jordan

Jordan was nowhere as prolific as the other writers on this list, but his first-hand experiences were in a class of their own; there may never have been a man faster with a handgun. His book, No Second Place Winner, has become a must-read for police-handgun enthusiasts, but you’ll need to dig up his magazine writings to really gain an appreciation for him. Someone could do his legacy and the shooting world a favor by anthologizing these pieces.

Jordan was nowhere as prolific as the other writers on this list, but his first-hand experiences were in a class of their own; there may never have been a man faster with a handgun. His book, No Second Place Winner, has become a must-read for police-handgun enthusiasts, but you’ll need to dig up his magazine writings to really gain an appreciation for him. Someone could do his legacy and the shooting world a favor by anthologizing these pieces.

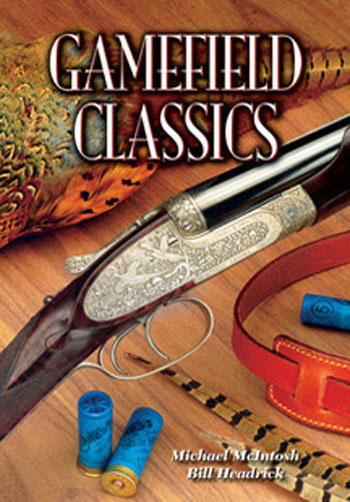

Michael McIntosh

McIntosh is the only writer listed here whom I knew personally, as we were both longtime columnists for Sporting Classics. McIntosh wrote with grace and a distinctive style, and he really knew shotguns. Mind you, his interests and knowledge ranged widely, but posterity will likely remember him, first and foremost, as a shotgun writer. His major works include Best Guns, Shotguns & Shooting, Shotgun Technicana, A. H. Fox: The Finest Gun in the World, The Big-Bore Rifle, and Gamefield Classics.

McIntosh is the only writer listed here whom I knew personally, as we were both longtime columnists for Sporting Classics. McIntosh wrote with grace and a distinctive style, and he really knew shotguns. Mind you, his interests and knowledge ranged widely, but posterity will likely remember him, first and foremost, as a shotgun writer. His major works include Best Guns, Shotguns & Shooting, Shotgun Technicana, A. H. Fox: The Finest Gun in the World, The Big-Bore Rifle, and Gamefield Classics.

I can already hear readers muttering, Where are George Nonte, Skeeter Skelton, Jim Carmichael, David Petzal, Sam Fadala, Bryce Towsley, “Pondoro” Taylor, Jeff Cooper, Terry Wieland, Wayne Van Zwoll and countless others? These writers are all of note but many are still living, while others are just not at the top of my preferences.

And then the Brigade Commander showed up!

And then the Brigade Commander showed up!

The American Airborne concept first suggested in World War I, became a need heading into World War II. The war started years before direct American involvement. The Airborne concept had to quickly yield results to support the allied cause, which at the time of its creation, was losing in both the Pacific and European theaters.

While there were no Airborne units in the American military, the airborne concept was nothing new to the Army. In 1918, it was Brigadier General William P. “Billy” Mitchell of the Army Air Corps, General John J. Pershing’s air service advisor in WWI, who first suggested the United States Army should utilize airborne troops.[1] Although “Black Jack” Pershing approved the idea, the concept never became reality due to the war ending of the war.

It would take another twenty-one years for the American Army to realize the paratroopers would be an important asset for future military operations. In 1939, when General George C. Marshall became the Army’s Chief of Staff, he made the recommendation to Major General George A. Lynch, Chief of the Infantry at the time, to “make a study for the purpose of determining the desirability of organizing, training and conducting tests of a small detachment of air infantry with a view to determine whether or not our Army should contain a unit or units of this nature.”[2]

Marshall recognized the potential and importance of possessing an Airborne asset. Even though some argued the Airborne concept was not a necessity for the Americans in WWII, General Marshall gave his approval on 25 July 1940. He authorized the War Department to immediately establish a Parachute Test Platoon to experiment with the development of airborne troops.[3]

Lieutenant General (Retired) Edward M. Flanagan defends the creation of the Airborne by pointing out in his book, Corregidor: The Rock Force Assault, the paratroopers served as a strategic asset with the ability to occupy the enemy commander’s mind for three reasons. First, while the enemy knows the airborne units exist, he does not know where they will strike.

Next, once they jump, the enemy must commit forces to engage the paratroopers, typically dropped over enemy vulnerabilities, such as their rear or flanks. Finally, the enemy never knows when the airborne attack might occur, leaving him in a constant state of high alert.[4]

Flanagan also highlighted that even when the drops were not a complete success and the paratroopers end up scattered, the enemy remained confused due to not knowing the size of the force, nor did he know where to concentrate his own force.

Because of how their drops disperse over a large area, paratroopers had the ability to deceive the enemy into thinking that their numbers were greater than what they actually were.[5] Flanagan cited Sicily as an example of the Airborne accomplishing this feat.

In Normandy, while the Airborne may not have succeeded in all of its D-Day objectives, it left the Germans in a constant state of confusion. The Airborne successfully defended the flanks and perimeter of the Normandy beachheads by freezing the German forces in place. The enemy’s confusion over an airborne drop easily became part of the element of surprise.

In the days following June 6th, 1944, the German Seventh Army chief of staff reported that “the ‘new weapon,’ the airborne troops, behind the coastal fortifications on the one hand, and their massive attack on our own counterattacking troops, on the other hand, have contributed significantly to the initial success of the enemy.”[6] From their appearance in the theater of war to the drops to the aftermath of the assault, paratroopers left their enemy in a disoriented and bewildered state. But before the Airborne would prove themselves on the battlefields of Europe, they had to start at the beginning, from scratch.

In late July 1940, the 48 original paratroopers, 2 officers, and 46 enlisted men began testing for the development of equipment, training, and techniques that would later be used in units dropped into harm’s way. Many of the developments created by this small group are still used to this day. This innovative group of young men performed testing that would claim two lives from their ranks. The platoon took courageous risks required to develop airborne capabilities for the entire American Army.

Among those in the Army, there were not many who knew much about parachutes or paratroopers at the start of WWII. However, at the start of the war, the Germans utilized their fallshirmjager, or paratroopers, in a few operations, stirring some interest in a few officers of the United States Army.

One was Lieutenant William T. Ryder, a 1936 graduate of West Point, who expressed interest in airborne operations long before the Army approved the formation of the Parachute Test Platoon. He studied Soviet and German tactics and training conducted in the late 1930s.

Prior to Ryder’s knowledge of the development of an airborne unit in the U.S. Army, Ryder submitted a number of papers to the Infantry Board covering the use of airborne units in combat.[7]

Ironically, when Lieutenant Ryder showed up with fifteen other officers who volunteered for the opportunity to lead the test platoon for a written exam, he was relieved to find the majority of the test covered articles he personally submitted to the Infantry Board in the past. In forty-five minutes, Ryder completed the two-hour examination and was quickly selected to command the test platoon.[8]

Five of the best Army Air Corps’ parachutists and riggers, led by Warrant Officer Harry “Tug” Wilson, conducted the training for the Parachute Test Platoon. [10] In the first two weeks, their training consisted of tough physical training combined with classes on the basics of the history of the parachute and its theories. Actual jumps were not performed because the platoon did not even have enough parachutes to conduct airborne training.[11] This was truly an outfit that evolved and developed its tactics with each jump.

By the third week, Major William H. Lee, the officer in charge of overseeing the development of the airborne units, sent the platoon to Hightstown, New Jersey. Major Lee discovered that due to the New York City World’s Fair in 1939, there were two 150-foot parachute jump towers his platoon could utilize for training. Later, 250-foot towers were built at Fort Benning to facilitate other paratroopers’ training. The platoon trained in New Jersey for ten days before returning to Georgia to finish their final two weeks of training.[12]

The platoon made great strides, and after its time in New Jersey, the men were in outstanding physical condition and could all pack their own chutes. On the last day of week seven, Lieutenant Ryder announced the completion of the ground phase of their training and the unit would make five jumps the following week.

After his announcement, “Tug” Wilson explained there would be a demonstration where a dummy would be dropped out of an airplane and parachute to the ground.[13] To the horror of every man at the demonstration, the dummy, nicknamed “Oscar,” was “pushed from the aircraft door, and plummeted to its destruction a mere 50 yards distance from the spectating volunteers.”[14] Fortunately for the men, it was only a test dummy.

Lieutenant Ryder, the leader of the platoon, was the first one out of the lead airplane for the inaugural jump, earning him the title of the “First American Paratrooper.”[15] Three more jumps followed the initial test, each one prompted rules and changes to be made to their equipment and techniques. One of these rules included the requirement that every jumper look off into the horizon when standing in the door, rather than looking down. This prevented the soldier from freezing in the doorway, keeping him from slowing down the entire stick’s progress during exit.[16]

The fifth jump the platoon conducted was to be a mass jump for a group of individuals requesting a demonstration of the accomplished work. The audience consisted of General Lynch, Major Lee, General Marshall, and, unannounced, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The performance of the jump greatly impressed those in attendance.

The audience witnessed the Parachute Test Platoon conduct the army’s “first airborne tactical operation with well-drilled precision.”[17] As a result of the platoon’s successes, the U.S. Army formed the first parachute battalion. By order of the War Department, on October 1st, 1940, the 501stParachute Infantry Battalion officially activated at Fort Benning.[18]

It took guts to volunteer to be a member of an Airborne unit, not just in combat, but in training as well. The Parachute Test Platoon represented some of the finest America had to offer. They were courageous individuals willing to pay the ultimate price for a military experiment that, at the time, did not even involve combat. They volunteered to help create an asset the Army deemed necessary to fight and win our nation’s wars.

Two short years later, rapidly promoted Major General William C. Lee, dubbed the “Father of American Airborne,” described these pioneers as “the fountainhead of the mighty airborne forces that wrote such glorious pages in the history of World War II.”[19] The Parachute Test Platoon paved the way for many others. Like those original, brave forty-eight, they volunteered to assume additional risk by joining the Airborne Paratroopers and jump out of an airplane, in training and eventually combat.

_____

[1] Edward M.Flanagan, AIRBORNE: A Combat History of American Airborne Forces, Presidio Press, 2002), 5.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Bennett M. Guthrie, Three Winds of Death, (Stillwater: New Forums Press, 2000), 3.

[4] Edward M.Flanagan, Corregidor: The Rock Force Assault, (Novato, Presidio Press, 1997), 101.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 201.

[7] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 10.

[8] Gerard M. Devlin, PARATROOPER!: The Saga Of U.S. Army And Marine Parachute And Glider Combat Troops During World War II, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979), 51.

[9] US Airborne[database online], (accessed 12 April 2005); available from

http://homeusers.brutele.be/sgteagle/welcometothealliedairborneheadquarters_usairborne.htm.

[10] Devlin, 53.

[11] John C. Andrews, Airborne Album: Volume One: Parachute Test Platoon To Normandy, (Williamstown: Phillips Publications, 1982), 4.

[12] Flanagan, 12.

[13] Devlin, 60.

[14] Andrews, 4.

[15] Andrews, 5.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Flanagan, AIRBORNE, 12.

[18] Ibid., 13.

[19] James M. Gavin, Airborne Warfare, (Washington: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), viii.

___________________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on June 2, 2019.

Mike Kelvington grew up in Akron, Ohio. He is an Infantry Officer in the U.S. Army with experience in special operations, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations over twelve deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, including with the 75th Ranger Regiment. He’s been awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Valor and two Purple Hearts for wounds sustained in combat. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, a Downing Scholar, and holds master’s degrees from both Princeton and Liberty Universities. The views expressed on this website are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or DoD.

This image of a smiling Mike Venturino has gotten lots of

attention in the wake of his passing. It’s how I hope we

all remember him.

The passing of American Handgunner and GUNS Magazine’s Mike “Duke” Venturino hit us, his colleagues and admirers, hard.

I cannot claim to have known him as well as I would have liked, but I knew him well enough to recognize a genuinely nice guy. We first met face-to-face on an airplane heading to a SHOT Show many years ago.

My flight stopped somewhere, and he came aboard, taking the seat next to me. There were the usual introductions, and for the next couple of hours, we talked about guns, gear and some of the folks we mutually knew.

There were plenty of chuckles a few shakes of heads, and maybe even an eye roll. It is surprising how fast about three hours can pass when the conversation is fun, and you’re talking to a new friend.

Duke was a writer’s writer; a fellow dedicated to detail and entertaining his readers as well as educating them. He attended Marshall University, where he studied journalism, which one could tell in an instant by the way he wrote, especially if you also studied journalism (University of Washington) some decades back in the 20th Century.

I learned of his passing at about 3 a.m. on a Monday morning and spent the next several hours finding out all I could before writing about it at TheGunMag.com, where being editor-in-chief sometimes includes the unpleasant job of writing about someone who has, as they say, “left the range.”

In all the years I’ve been writing about firearms and reading what others wrote — and the reactions from readers — I cannot recall a single person ever disparaging Mike Venturino.

More than 35 years ago, one of my long-gone shooting/hunting buddies remarked about having read something he wrote with a connection to the gun-related thing we were discussing. “Well, Venturino said …” This seems to have been stated over the years by more people than I can count. Translation: Mike’s observations were the gold standard.

Safe in Seattle?

Back in 2020, I was working on a column about the events of the Old West in 1876, which included a mention of the Custer debacle at Little Bighorn. I was interested in the ammunition 7th Cavalry troopers used in their Colt SAA revolvers, so I reached out to Venturino, who was the only guy on the planet I figured would have the information. We were Facebook “friends” by then, so I fired off a message.

Two hours later, I got a reply. Duke was matter-of-fact, explaining they used “standard .45 Colt rounds. They were loaded with 30 grains (of) black powder and 250-grain bullets,” to which he added, “I have a photo of an original box that belongs to a friend. It is dated January 1874 and has those specs on the label.” Why didn’t that surprise me? He was a living encyclopedia of gun stuff.

And then he added a comment, mindful of the insanity of the protests going on at the time in Seattle where what the ex-mayor flippantly — and ignorantly — described as the “summer of love” was unfolding in broken glass, vandalized police vehicles, some looting, property damage and a couple of murders following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

“I hope you are surviving all the crap over your way,” he wrote, and I knew he meant it. I still consider it a very thoughtful thing to say.

A couple of years later, I was researching another piece, doing some background, when something triggered my recollection of a teacher in junior high school telling me about how he and some buddies had allegedly once drilled out a .44-caliber bullet and inserted an inverted .22 Short case, presumably with the powder intact, to make an “exploding” projectile. I have no idea whether he was telling a tale, but I remembered it more than 50 years later. It was and remains one of the all-time stupidest things I’ve ever heard of. Ultimately, this moronic stunt had nothing to do with the story I was working on, but I sent Duke a note anyway, asking if he’d ever heard of such a harebrained stunt.

Kids … and adults … do NOT try this at home or anywhere else. Run, don’t walk, away from anybody who suggests giving this a try.

“I have heard of that,” Mike replied about four hours later, “but I’m like you. It’s harebrained!”

About 18 months ago, I inquired about what kind of computer he used, as I was prepping to replace my aging desktop. I still get a chuckle from his reply: “I have no idea what it actually is except it uses Apple stuff. I just told a local guy that I needed a new computer, and he came and set it up.”

Mike and I obviously had more in common than just guns!

Still, our exchanges stuck mainly to guns. Last July, I sent a message to tell him how much I enjoyed a story he did on snake loads. At the time, I had a 25-pound bag of tiny lead shot I planned to bring over last summer if I had a chance to get to Montana. I never got to make that trip, and now it is too late. The moral: If you want to do something for a pal, do it. Next year may be too late.

‘They Don’t Make ‘Em…’

People like Mike Venturino happen once in a great while, possibly once in anyone’s lifetime — if even that frequently. Guys like him are very rare indeed and the best thing one journalist can say about another is this: “I shall miss his byline.”

He authored books and a few thousand stories during his career of about 50 years. That was one heck of a lifetime. I will think good thoughts about Duke at the campfire.

Operations in the Dominican Republic, Part III

The caliber of enlisted Marines serving in the DomRep also changed over time. Initially, the NCOs were old salts; men who had served in the Spanish-American or Philippine Insurrection. These were often tough old bastards who liked to drink but were always able to carry out their duties with courage and intellect.

After the commencement of a military draft in 1917, not all enlisted men had the temperament needed for independent duty. In fact, some of these Marines were so poorly trained that they were dangerous to themselves and their fellow Marines. Serving in the 15th Regiment was a First Lieutenant (temporary captain) named Edward A. Craig [5]. When Craig joined his company in 1919, he found his men lacking in certain areas of fieldcraft, in marksmanship, in discipline, and in ability. To correct this deficiency, Captain Craig gathered together two experienced NCOs and told them to “fix the damn problem with these Marines.” They did, and Craig’s company later distinguished itself in the Dominican country side. There is no substitute for good NCO leadership.

And then there were the Marines who volunteered for service in World War I only to find themselves assigned to a Dominican backwater. They were a disgruntled lot and didn’t care who knew it. All of these Marines lived in the field —very few of them getting to pull liberty in Santo Domingo City. Their homes were the villages and small towns. They lived in primitive tent camps or in insect-infested native huts. Their rations were meager, consisting mostly of canned meat, vegetables, bacon, flour, and other nonperishables. Typical of Marines even today, they often traded their government rations with natives for fresh eggs and chickens, if the poor natives had any to spare. Occasionally an enterprising Marine encountered a cow being held against its will and liberated it.

Food and water became a serious problem during extended patrols. Marines took with them food and water rations, of course, but if these ran out the Marines were forced to forage for food on their own. Even with hunger pangs, the Marines were always mindful of not taking food from the mouths of local native —but one does have to survive. And, despite Colonel Pendleton’s stern letter about what he expected of his Marines, those who served in the countryside sometimes engaged in illegal activities —the things Pendleton expressly forbade. A few Marines extorted money and goods from the natives, made arbitrary arrests, fought with civilians or among themselves, and stealing government property sold it to the natives. Whenever Marines were caught doing such things, they were court-martialed and severely punished.

Captain Charles F. Merkel was accused of severely beating and disfiguring a native prisoner, and for ordering four other Dominicans shot near Hato Mayor in the Eastern district. Major Robert S. Kingsbury conducted an investigation and based on his findings of fact, arrested Merkel and confined him to quarters awaiting trial. Merkel took his own life before trial.

Clearly, however, most Marines acquitted themselves with honor and distinction during the occupation of the Dominican Republic. They were well-disciplined, law-abiding, and they discharged their duties at levels at or above their pay grade under the most difficult of conditions. They exhibited skill, patience, and esprit-de-corps in the fulfillment of suppressing banditry, training native constabulary, and civil administration.

Throughout the Marine Corps experience in the Dominican Republic, hardly a month went by when there wasn’t a clash between Marines and “bandits.” Back then, “bandit” was a label attached to anyone suspected of being an enemy —much in the same way Marines applied the label “VC” to Vietnamese civilians (whether or not true), if they looked at a Marine with hateful or suspicious looks. A civilian may think that suspicion is a horrible way to live your life —and this may be true— but Marines aren’t paranoid when people really are trying to kill them.

In the DomRep, bandits were not homogeneous. Some were highway men (gavilleros), others were politicians who used natives to advance their own ambitions. Some were unemployed laborers whose level of poverty drove them into a bandit camp. Some were common peasants pressed into service. And then there were the professional criminals: murderers, kidnappers, and thieves. Most of the Dominican people were none of these.

Bandit bands seldom ever exceeded around 200 in number; most around 50 in number. They robbed and terrorized rural communities, extorted money, confiscated ammunition, stole supplies from the sugar plantations, and some even had the courage (or stupidity) to attack a Marine patrol. For the Marines, the bandits seemed ever present. It was stressful duty. And while many of the bandits were little more than hoodlums, there were also quite dangerous warlords. When bandit groups of any size believed that they had an advantage over the Marines, they would fall upon them with machetes and knives. Marine rifle and machine gun fire usually worked to discourage such attacks, but not always.

In addition to courageous skill in the combat arms, the Marines had another advantage: Marine Aviation. The 1st Air Squadron joined the occupation force early in 1919. The squadron commander was Captain Walter E. McCaughtry, a pilot of some skill who had risen from the warrant officer ranks. Initially, the squadron was equipped with six JN-6 (Jenny) bi-planes. Air operations began from an airstrip hacked out of the dense jungle near Consuelo, 12-miles from San Pedro de Macoris. When the squadron was moved to a field outside Santo Domingo City, it was re-equipped with DeHaviland (DH)-4Bs. The DH-4B was a single engine, two-seat bi-plane improved from World War I day bombers. It was sturdy, maneuverable, and versatile.

In addition to courageous skill in the combat arms, the Marines had another advantage: Marine Aviation. The 1st Air Squadron joined the occupation force early in 1919. The squadron commander was Captain Walter E. McCaughtry, a pilot of some skill who had risen from the warrant officer ranks. Initially, the squadron was equipped with six JN-6 (Jenny) bi-planes. Air operations began from an airstrip hacked out of the dense jungle near Consuelo, 12-miles from San Pedro de Macoris. When the squadron was moved to a field outside Santo Domingo City, it was re-equipped with DeHaviland (DH)-4Bs. The DH-4B was a single engine, two-seat bi-plane improved from World War I day bombers. It was sturdy, maneuverable, and versatile.

In December 1920, 1st Air Squadron received a new commanding officer, Major Alfred A. Cunningham —the Marine Corps’ first aviator. Cunningham had organized and led the 1st Marine Aviation Force in France during World War I. He was transferred to the DomRep after serving as Director of Marine Corps aviation. Cunningham was later replaced by Major Edwin A. Brainard, who remained with the squadron until the end of occupation duty. 1st Air Squadron had an average strength of 10 officers and 130 enlisted men. It took a lot of men to keep six aircraft operational.

Flying combat missions in the Dominican Republic was no piece of cake. Mountainous terrain made flying conditions difficult and dangerous. With a lack of airfields, an in-flight emergency could produce disastrous results. At this time, there were no navigational aids and the difficulties of aircraft maintenance were complicated by the logistics train.

On 22 July 1919, Second Lieutenant Manson C. Carpenter and his observer/rear gunner, Second Lieutenant Nathan S. Noble undertook a mission communicated to them by telephone of a skirmish near Guaybo Dulce. A Marine patrol reported 30 mounted bandits fleeing across an open meadow. Carpenter conducted a strafing attack, diving from an altitude of about 100 feet and then maneuvering in such a way that brought both his front and rear cockpit guns to bear. As Carpenter climbed to regain altitude before beginning another run, the bandits scattered into the tree-line. During his second pass, Carpenter counted six bodies. It was a successful mission —but the truth is that these kinds of engagements were rare. There were no sophisticated air-to-air/air-to-ground communications —and this meant there was also no transmission of timely intelligence, no coordination of field operations. But this was in the early stages of Marine Aviation and all of this would change in the not-too-distant future.

Marine Aviation’s greatest value lay in its support role. 1st Air Squadron carried mail and passengers from major cities to outlying districts and towns. They also delivered much-needed supplies to remote units and evacuated wounded Marines —the first application of aeromedical evacuation. By 1922, Marine aviators were helping ground commanders control operations in widely dispersed areas by dropping messages to them from the air and keeping the regimental headquarters informed of the whereabouts of ground elements. Marine pilots also conducted aerial surveys of the Dominican coastline, mapping important rivers, and developing photographic maps. The regiments also sent newly arrived company officers up in planes to orient them to the areas they would later patrol on foot. Dominican operations were significant, too, in another respect: they enabled the Marine aviators to demonstrate their value to Marine ground forces. DomRep was the birthplace of the Marine Corps Air-Ground team.

In mid-1922, the 2nd Brigade commander summarized operations since 1916. His report concluded that the Marines had engaged with bandits on 467 occasions. Bandit losses exceeded 1,100 killed or wounded, with Marine loses of 20 killed and 67 wounded. Most of these contacts transpired from within the Eastern District. With the passage of time, bandits became more difficult to engage because they rarely attacked Marine security patrols. It was easier (and safer) for bandits to focus their attentions on unarmed peasants. The problem for Marines were three: (1) a paucity of accurate and timely intelligence; (2) a lack of communications with and among scattered units —noting that field radios were sent to the Marines in late 1921; (3) the absence of effective planning and coordination of security patrols. Normally, regimental headquarters had no clear idea where their Marines were located. Frequently, patrols from two or three commands were discovered operating in the same area, each of these unaware of the other’s presence.

By 1921, senior Marine commanders realized that time was running out and they still had not solved the bandit problem. Brigadier General Harry Lee wanted to step up ground operations. Colonel William C. Harllee [6], then commanding the 15th Regiment, launched a systematic drive to finish off the bandits operating in the Eastern District. Between October 1921 and March 1922, Harllee employed his entire regiment, reinforced by the newly created Policia Nacional, in a series of large-scale cordon operations in Seibo and Macoris. Harllee’s scheme involved a series of encirclements that were coordinated through the use of newly received field radios and air-dropped messages.

Harllee’s search and destroy maneuvers dispatched more than a few bandits and netted 600 or so “suspected” bandits. General Lee halted the cordon operations, however, because they proved unpopular with the local peasantry. Harllee reverted to security patrols, better coordinated by the introduction of field radios, and these resulted in seven enemy engagements.

In March 1922, General Lee implemented the formation of “home guard” units at Consuelo, Santa Fe, La Paja, Hato Mayor, and Seibo. Home guard units consisted of around 15 men each, accepted for service upon the recommendation of municipal officials. They were generally men who had suffered depredation at the hands of bandits and were therefore eager to serve their communities. Trained, armed, and led by Marines, home guard units patrolled their own localities. Two or three Marines armed with automatic weapons reinforced home guards units. General Lee’s plan was the precursor to Combined Action Platoon (CAP) operations used in the Viet Nam War.

Between 19-30 April 1922, home guard units effectively destroyed six bandit groups. General Lee believed that these home guard units, more than any other single factor, broke up banditry in the Eastern District. In late April, prominent Dominicans acting under the authority of the Military governor negotiated the surrender of one of the more prominent bandit leaders. Subsequently, seven more of these brigands surrendered to the Marines —along with 170 of their followers. In exchange for voluntarily surrendering, they received suspended sentences so long as they maintained good behavior. In June 1922, General Lee reported that all banditry in the Eastern district had ceased. The Dominican Republic was pacified.

With the success of anti-bandit operations, the Marines could then concentrate on the training of an efficient national constabulary. It was a necessary step in safeguarding all the hard work that had been theretofore accomplished. Previously, the Dominican Guardiahad been untrained, prone to loyalty toward charismatic leaders rather than to their duly elected national authority. Most, if not all, Guardia officers were corrupt. Those who shared their booty with their men were most popular of all. More than this, Guardia officers were too easily persuaded to become the useful tools of corrupt politicians. It was President Henriques’ refusal to accept the creation of an American-trained constabulary that led to American occupation to begin with. Corruption was so deeply engrained that the only possible solution was to completely disband the Guardia.

This was accomplished on 7 April 1917, when the military governor created a new national police force, called the Guardia Nacional Dominicana (GND). The GND replaced the Dominican Army, Navy, Guardia Republicana, and frontier guard. The GND would be staffed with 88 officers and 1,200 enlisted men. Initially, the GND was placed under the command of a Marine officer, who answered to the Commanding General, 2nd Brigade. Over time, the GND created its own headquarters staff and territorial organization, which paralleled the organizational structure of the Marine brigade. One company of GND was assigned to each province. In 1920, half of the GND’s officers were still U. S. Marines, officers and NCOs [7] who accepted Dominican commissions. Developing native officers was a long process of reforming attitudes and teaching them good leadership principles. Culture (corruption) was always an impediment to this process.

The GND enlisted force was entirely composed of natives. They earned $17.00 per month, which was a hefty amount of money considering that they were accustomed to working for twenty-five cents per day, or around $7.50 per month.

Part of the difficulty of training the GND was the frequent reassignment of its senior (Marine) officers. Generally, assignment to the GND involved a seven-month rotation. Added to this, all Marine officers were overloaded with additional duties. Under these circumstances, combined with rapid deployments of GND forces to deal with bandits in outlying areas, effective training was significantly impaired. Budget cuts were another stopgap to effective training. At one point in 1921, the GND was reduced by 346 men simply because there was not enough money to pay them. Arming the GND was another problem —that and providing them with horses and motorized transportation.

Despite so many handicaps, the GND ably assisted US Marines in their campaign against banditry and then taking pacification to the next level: security for all. In 1921, the United States committed itself to an early withdrawal from the Dominican Republic. Marines intensified their efforts to develop the GND into a fully professional force. The GND was renamed Policia Nacional Dominicana (PND) to emphasize the character and mission of the organization. A new recruiting effort began, along with an effort to weed out less desirable veterans. By August 1922, the PND fielded a force of 800 men, its ceiling remaining at 1,200.

No one did more to guarantee the success of the PND than Lieutenant Colonel Presley Marion Rixey [8] who served as its commandant from 1921 to 1923. Rixey was a superb combat commander and administrator who served on the Brigade staff before assuming command of the PND. He transformed the PND into a highly mobile and strategically placed police agency and was responsible for the creation of two police training centers which included a five-month course of instruction for mid-level officers, including administration, tactics, weapons, topography, first aid, hygiene, and agriculture.

Training courses were also designed for enlisted men lasting two months. Training emphasized guard duty, discipline, personal cleanliness, hygiene, and marksmanship. An emphasis on marksmanship gave the PND a distinct advantage over bandits and other criminals. Marines worked hard to inculcate unit pride and esprit de corps with emphasis on winning the confidence of the Dominican people, treating them fairly and consistently, offering them more than protection, but also justice.

Nevertheless, it had come time for the United States to return control of the Dominican Republic to the people. President Warren G. Harding, Wilson’s successor, worked to end the occupation —which was something he promised to do during his campaign for the presidency. In 1924, the Marines packed up and went home, leaving behind them a nation with a stable economy, a countryside free of bandits, and a national police organization capable of maintaining the peace. Would these police officials acquit themselves with honor and integrity?

One of these young police officers was Rafael Leonidas Trujillo, who was in the first class to graduate from the academy at Haina. Trujillo was born near San Cristobal in 1891. Most of his youth was spent drifting in and out of minor jobs and petty crime. In 1916, he obtained a respectable job as a security officer on a sugar plantation. He was attracted to the exciting life, so in 1918, he applied for a commission in the GND. He was sworn in as a second lieutenant in January 1919. Stationed with the 11thGuardia Company at Seibo, Trujillo earned good efficiency reports from his superiors. On one occasion, however, he was placed under arrest for allegedly attempting to extort money from a civilian. These charges were dismissed before trial.

One of these young police officers was Rafael Leonidas Trujillo, who was in the first class to graduate from the academy at Haina. Trujillo was born near San Cristobal in 1891. Most of his youth was spent drifting in and out of minor jobs and petty crime. In 1916, he obtained a respectable job as a security officer on a sugar plantation. He was attracted to the exciting life, so in 1918, he applied for a commission in the GND. He was sworn in as a second lieutenant in January 1919. Stationed with the 11thGuardia Company at Seibo, Trujillo earned good efficiency reports from his superiors. On one occasion, however, he was placed under arrest for allegedly attempting to extort money from a civilian. These charges were dismissed before trial.

After graduation, Trujillo rose rapidly through the ranks of the PND. After the Marines departed the Dominican Republic, Trujillo was advanced from second lieutenant to major. In 1924, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assumed the post of chief of staff of the PND.

In the elections of 1924, the Dominican people elected Horacio Vásquez. Vásquez had cooperated with the American occupation force. He gave the Dominican Republic six years of stable and successful government, one in which political and civil rights were respected and the economy became vibrant in a country with a peaceful atmosphere.

Under Vásquez, Trujillo was advanced again to Colonel Commandant of the PND. In 1930, when Vásquez attempted another term as president, his political opponents made a deal with Colonel Trujillo. The deal was that Trujillo would stand back and do nothing if Rafael Estrella Ureña overthrew the Vásquez government. As promised, Trujillo ordered his men to remain confined to barracks as Ureña marched on the capital. After Ureña was proclaimed acting president, he appointed Trujillo to command the national police and armed forces. In this capacity, Trujillo announced himself as a candidate as Presidency of the Dominican Republic. During the “campaign,” Trujillo unleased his police and army forces to repress all political opponents. He was elected president unopposed, ascending to power in August 1930. Trujillo become the Caribbean’s longest-lived and more feared dictators. He was assassinated on 30 May 1961.

In February 1963, Juan Bosch was elected president of the Dominican Republic. He was overthrown on 24 April 1965. After nineteen months of military rule, the people revolted. US President Lyndon Johnson, concerned that communists may seize power and create a second Cuba, sent the Marines back to the Dominican Republic to restore order. As part of Operation Powerpack, Johnson authorized the US 82nd Airborne to occupy the DomRep. They were soon joined by a small military contingent from the Organization of American States. Foreign military forces remained in the DomRep for well over a year, departing after supervising presidential elections in 1966. President Joaquin Balaguer remained in power for 12 years.

In retrospect, the performance of the United States Military Government (of which the 2nd Marine Brigade was its most conspicuous agent) and the American policy of Caribbean intervention, remains controversial. By improving communications, transportation networks, promoting education and public health, and improving police and other government agencies, the Marines did much to establish an infrastructure for success. There was one failure, however. No matter how much money was expended improving local conditions, the United States Marines could not have created a stable Dominican democracy. This can only be accomplished by a people who most desire it and who have the means and the will to achieve it [9]. It is a lesson unlearned by modern American diplomats and senior military advisors in Washington, D. C.

Today, the Dominican Republic has the ninth largest economy in Latin America and the largest economy in the Caribbean/Central American region, bolstered by construction, manufacturing, tourism, and mining. The Dominican people have achieved what most other Hispanic societies in the Americas never have: a political environment within which a free and independent people may succeed.

Sources:

- Wiarda, H. J. and Michael J. Kryzanek. The Dominican Republic: A Caribbean Crucible. Boulder: Westview Press, 1982

- Diamond, J. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books, 2005

- Fuller, S. M., and Graham A. Cosmas. Marines in the Dominican Republic, 1916-1924. History and Museums Division, U. S. Marine Corps, 1974

Endnotes:

[1] Ben Hebard Fuller (1870-1937) initially joined the US Navy (1889-1891) and then served in the Marine Corps (1891-1934). His final post was Major General Commandant of the Marine Corps from 1930-1934. General Fuller was laid to rest next to his son, Captain Edward C. Fuller of the 6th Marines, who was killed in action during the Battle of Belleau Wood in World War I.

[2] Logan Feland (1869-1936) initially served in the Volunteer Infantry (1898-1899) and served as a US Marine (1899-1933). Among his several duty stations, General Feland served during the Spanish-American War, World War I, and several of the so-called Banana Wars. Feland retired as a Major General commanding the Department of the Pacific. He was a recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross (Army), Distinguished Service Medal (Army), Distinguished Service Medal (Navy), five Silver Star medals, and the French Legion of Honor.

[3] Charles G. Long (1869-1943) served in the USMC from 1891-1921. Major General Long served in the Philippine-American War, Spanish-American War, Boxer Rebellion, World War I, and during the so-called Banana Wars. General Long was the recipient of the Marine Corps Brevet Medal and the Navy Cross.

[4] Harry Lee (1872-1935) served in the Marine Corps from 1898-1933. Lee commanded the 6thMarine Regiment, Marine Barracks, Parris Island, Marine Corps Base, Quantico, and the 2ndProvisional Brigade while serving as Military Governor of the Dominican Republic. He served in the Spanish-American War, World War I, and during the so-called Banana Wars. Retiring as a major general, Lee was the recipient of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star medal, and Legion of Honor.

[5] See also: Edward A. Craig—Marine.

[6] William Curry Harllee (1877-1944), referred to as Bo by his friends, was a large man who stood over 6’2” tall and weighed 200 pounds. His military service began with some difficulty. He was expelled from the Citadel for having accumulated excessive demerits, and later expelled from the U. S. Military Academy (where he ranked second in his class) for being too willful and too independent for military service. In 1899, Corporal Harllee distinguished himself during the Philippine Insurrection of 1899 while serving with the 33rdUS Volunteer Infantry. In 1900, he finished first among applicants for a commission in the U. S. Marine Corps. He was nearly court-martialed in 1917 for repudiating the “dead wood” in charge of the US military. Harllee was advanced to Brigadier General upon his retirement and is remembered as a no-nonsense, tough, and completely politically-incorrect ground officer. Harllee was laid to rest next to John A. Lejeune at Arlington National Cemetery.

[7] The GND officer corps also consisted of US civilians having a law enforcement background in the United States.

[8] Presley Marion Rixey (1879-c.1949) was the nephew of Rear Admiral Presley M. Rixey, USN, Surgeon General of the United States Navy and personal physician to Presidents McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Colonel Rixey served in the Marine Corps from 1900-1936 serving variously as Commanding Officer, 2nd Marines, 1st Marine Brigade, and Commander of the Legation Guard, Peking, China. Colonel Rixey’s son was Brigadier General Presley Morehead Rixey, USMC (1904-1989).

[9] Most Hispanic societies in the Americas continue to struggle —this has been the over-arching legacy of Spanish culture.