Test firing Colt Digger

The Green Machine at work

Today the Model 1917 rifle is widely recognized as a robust and reliable weapon that helped the Allies win World War I. But initially, it faced great prejudice and caused no little scandal when the public found out that an “inferior” British weapon would be arming our boys over there. As word trickled out that American “Doughboys” were going to be armed with English rifles, letters of inquiry, advice, and condemnation soon came winging their way to the War and Ordnance Departments.

Then Col. (retired) John Thompson and Brig. Gen. William Crozier (the Chief of Ordnance) seem to have spent a fair amount of their time responding to members of Congress and prominent citizens across the country who wrote to express their concerns.

Even more alarming was a half-page (and half-baked) article in New York’s The Sun published on June 17, 1917. The headline blared, “WHY OUR FORCES IN FRANCE MUST USE INFERIOR RIFLE,” followed by the subheading “Our Expeditionary Troops to Be Armed With Lee-Enfields Because Our Own Springfields Can’t Be Turned Out Fast Enough” – showing that the “Enfield” designation, erroneously given to the Pattern 14, caused quite a stir when it was let slip that U.S. forces would be armed with a modified Pattern 14.

Drawn primarily from the Ordnance Reserve Corps and National Guard, the officers assigned as rifle demonstrators were responsible for training the men of the rapidly growing American Expeditionary Force on the M1917 rifle.

Drawn primarily from the Ordnance Reserve Corps and National Guard, the officers assigned as rifle demonstrators were responsible for training the men of the rapidly growing American Expeditionary Force on the M1917 rifle.

Such troubles had been clearly anticipated by Lt. Col. Webley Hope, a British officer responsible for inspecting Pattern 14 rifles in America, who had implored Brig. Gen. Crozier a month earlier to shun the word “Enfield” for three reasons. First, it was not the official British nomenclature for the Pattern 14, and the attachment of the term “Enfield” was an error made in the early days of the war. Second, he felt “it would be anomalous to give this name to a rifle which requires modification in so many ways in order to take [the U.S.] cartridge”. And third, was “the importance of the new rifle not being confused with the British Lee-Enfield rifle…”

In part due to this timely intervention, the modified rifles were officially named “U.S. Rifle, Model of 1917,” and were to be stamped accordingly when production got underway later that spring.

Despite a rocky start and vocal public concern, by September 1917 enough M1917 rifles were available for limited issue. Towards that end Brig. Gen. Crozier requested of the Army’s Adjutant General that “several companies of regular troops and several companies of National Guard, distributed among several stations and cantonments, be equipped with the first lot of these rifles and that a careful record be kept of the criticisms, experience and of whatever tests they make of the rifles.”

This was followed by a more detailed proposition on Nov. 24, 1917, which formally requested the authorization of “Demonstrators of the U.S. Rifle, Model of 1917.” These select officers of the Ordnance Reserve Corps and the Ordnance Departments of the National Guard, touted as having national reputations as rifle and revolver shots, were to be “given a course of instruction with the new rifle, so that they will be thoroughly familiar with it.” While their fellow soldiers and officers look on, soldiers take aim on the Camp Funston, Kan., rifle range.

While their fellow soldiers and officers look on, soldiers take aim on the Camp Funston, Kan., rifle range.

The recently promoted Maj. Gen. Crozier fleshed out the plan by stating that these officers be sent to “the various National Army Camps for short periods, for the purpose of demonstrating the U.S. Rifles, Model of 1917, [and] giving such assistance and advice in regard to small arms target practice…” He went on to give the rationale for this action by making the case that “The reports of these officers on the behavior of the new rifle and cartridge will be of considerable use to [the Ordnance Department], particularly at this time when the manufacture of the rifle in large quantities per day has just begun.”

While it was perhaps unsaid, or maybe developed over time, these rifle demonstrators would also become the evangelists for this new, strange, foreign designed rifle – seeking converts amongst both seasoned soldiers and newly inducted trainees.

The instruction they would give not only covered rifle basics, general marksmanship and weapons care, but also addressed the “why?” in the form of telling the tale of both the history and purpose of the M1917.

Additionally, since their number was quite small (seemingly no more than 40 men), the rifle demonstrators needed to “train the trainers” by preparing both the commissioned and non-commissioned officers of the various divisions to provide competent instruction to their own formations.

Beyond the above tasks, rifle demonstrators would also be pulled in other directions, often at either their own whims, or the whims of the officers commanding the divisions they were training or training camps on which they were located. In the end, their job would be as much for building morale as it was for technical weapons training.

The Men of the Rifle Demonstrator Program

The man chosen for the job of managing the rifle demonstrators was one already well respected in military munitions circles, but who had yet to achieve the legendary status he would eventually gain post-war. Col. (retired) John T. Thompson was working as the Chief Engineer at Remington Arms when the U.S. entered the war, and had been instrumental in building the Eddystone rifle factory.

As probably the single most knowledgeable American citizen regarding Pattern 14 production, he was a natural choice to take on the additional title of “Advisory Engineer, In Charge of Rifle Demonstrators.”

In that position he was responsible for taking reports from the rifle demonstrators, who would write him with their impressions, activities, issues, complaints and successes.

Fortunately, a number of these reports have been preserved in the National Archives and digitized by the Archival Research Group, providing some incredible insight into the efforts undertaken by the men responsible for fielding the M1917 rifle.

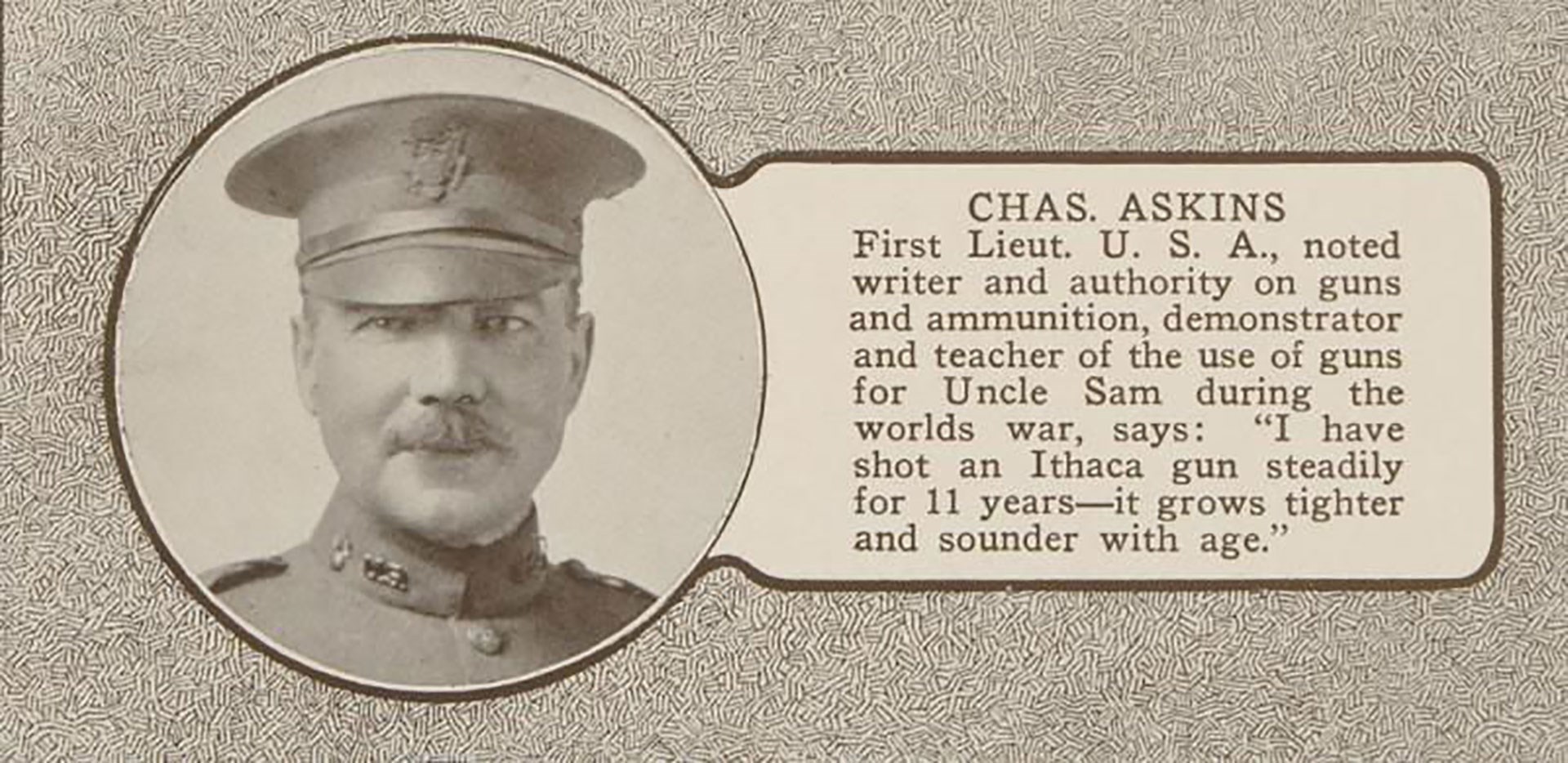

Charles Askins Sr., already a well respected shotgunner and gun writer, brought his knowledge and skills to his role as a rifle demonstrator.

Charles Askins Sr., already a well respected shotgunner and gun writer, brought his knowledge and skills to his role as a rifle demonstrator.

Those chosen to be demonstrators included men of note as well. Then 1st Lt. Charles Askins Sr. (more commonly known by his later rank of Major) was already an accomplished gun writer, having published The American Shotgun, and would later go on to publish numerous other titles such as Shotgun-ology, Modern Shotguns and Loads and Game Bird Shooting.

He also was the father to Charles Askins Jr., who eclipsed the fame of his father by being a renowned gunfighter, lawman, Army officer, handgunner and gun writer responsible for nearly countless articles and books.

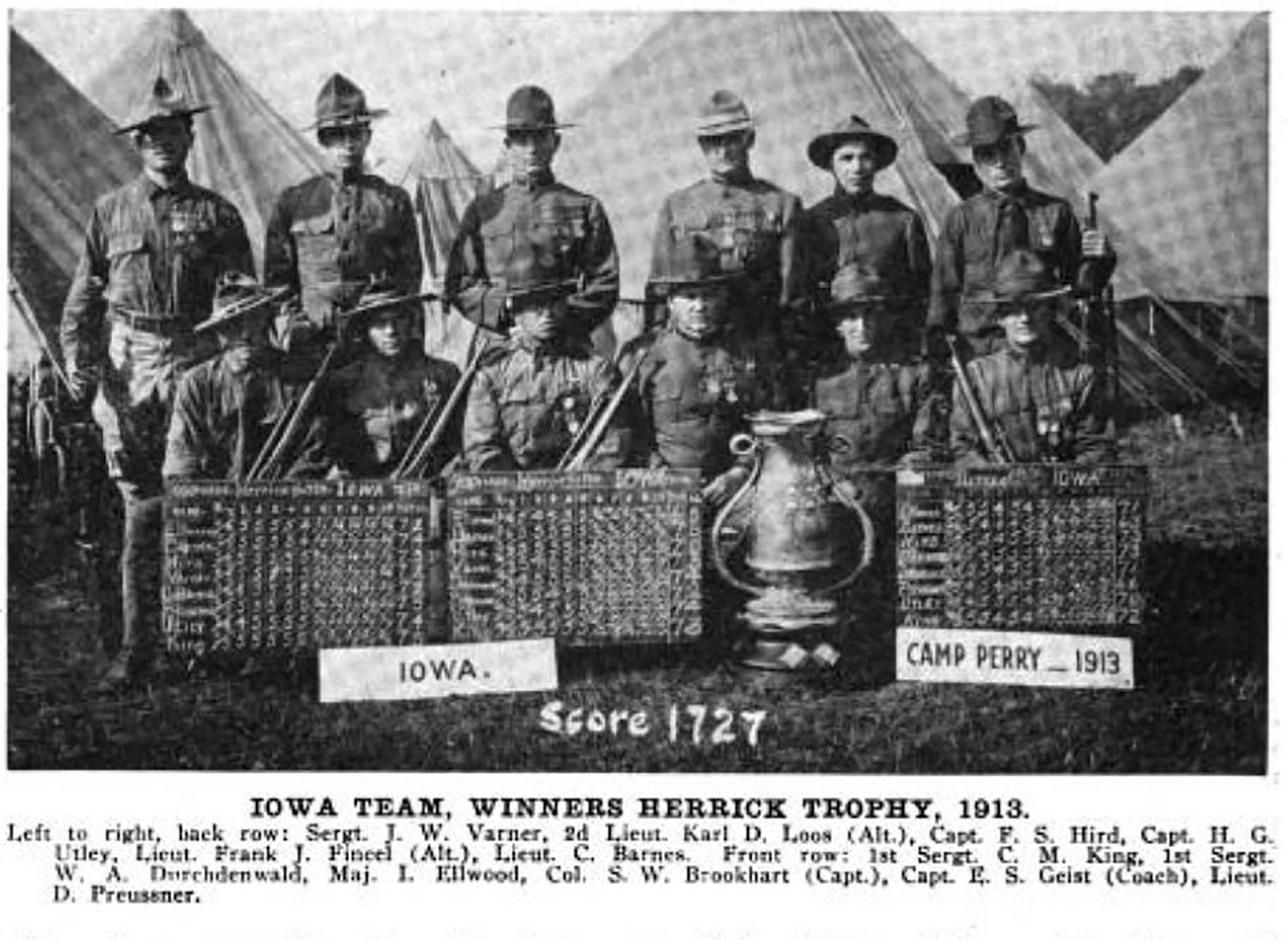

Others, like Capt. Don Preussner and 1st Lt. Karl Loos were already accomplished military rifleman, having participated in rifle competitions leading up to the World War I. In fact, both men had been at Camp Perry in 1913 as part of the Iowa National Guard team that won the Herrick Trophy at the National Matches, with their victory being highlighted in American Rifleman predecessor Arms and the Man.

The course of fire required the eight-man firing team, while prone, to fire 15 shots each at targets at 800, 900 and 1,000 yards.

Only six months before the U.S. entered the war, Capt. Preussner, again shooting for Iowa, captured the Marine Corps Cup at the National Matches by shooting an impressive 196 out of 200 while engaging targets at 600 and 1,000 yards with a Model 1903. Capt. Preussner would remain a member of the Iowa National Guard throughout the war, while Lt. Loos accepted a commission in the Ordnance Reserve Corps.

Clustered around the impressive Herrick Trophy they just won, two future rifle demonstrators stare at the camera. Lt. Loos stands second from the left, and then Lt. Preussner is seated at far right.

Clustered around the impressive Herrick Trophy they just won, two future rifle demonstrators stare at the camera. Lt. Loos stands second from the left, and then Lt. Preussner is seated at far right.

Many, like Capt. Mortimer Munn, had long military service with state forces prior to the outbreak of war. Munn first enlisted with the State of New Jersey in 1891, serving through the ranks as a Private, Corporal, Sergeant, First Sergeant, Sergeant Major, Lieutenant and Captain, before accepting the rank of First Sergeant with 1st New Jersey Volunteer Infantry during the Spanish-American War.

After that war, Munn seems to have reverted back into the New Jersey National Guard as an officer, until accepting a commission as a Captain in the Ordnance Reserves Corps in January 1918.

“Compared to the Springfield Rifle, a Certain Amount of Prejudice Prevails”

The job of actually “selling” the M1917 to the troops would not be an entirely easy one for the newly assigned rifle demonstrators, especially since it was supplanting a well-liked and well-respected rifle in the M1903. Capt. Fred Morris, reporting from Camp Sevier in South Carolina, stated that “Compared to the Springfield Rifle, [M]odel 1903 a certain amount of prejudice prevails against the U.S. Rifle, [M]odel 1917, which most likely will be overcome with a demonstration of its superiority…” Among other things he noted a “Difficult bolt action, especially in rapid fire, the application of the additional power necessary to fully cock the piece.”

Three of the most readily identifiable features of the M1917 rifle are the pistol grip stock, crooked bolt, and rear sight protector wings.

Three of the most readily identifiable features of the M1917 rifle are the pistol grip stock, crooked bolt, and rear sight protector wings.

The cock-on-close bolt was certainly a point of consternation for shooters familiar and comfortable with the “more American” cock-on-opening. Capt. Preussner, writing from Camp Funston, Kan., chose to explain that the M1917 bolt “is designed to perform just one function at a time,” compared to the M1903 “which has to perform two important functions at the same time while the bolt handle is being raised.” To men familiar with the M1903, he chose to concede that the Springfield was easier to manipulate in rapid fire, but that the same effect could be achieved with “persistent and extensive practice.”

Capt. Munn, operating out of Camp Lee, Va., adopted a more positive strategy regarding the M1917 bolt by hailing it (and the whole rifle) as having been designed especially for modern warfare and instructed his students that, “Even the crook in the Bolt Handle, means valuable seconds, for as an improvement over other models, it brings the index finger naturally into position, for pulling the trigger without lost motion. We must get in two shots to the ‘Boche’s’ one, when he sticks his head ‘Over the Top.’”

The rear sight features a pair of generously sized apertures — one on the battle sight, and the other on the slider which is adjustable for ranges out to 1,600 yards.

The rear sight features a pair of generously sized apertures — one on the battle sight, and the other on the slider which is adjustable for ranges out to 1,600 yards.

The peep-style aperture sights were also a marked departure from the M1903. While the M1903 does have a tiny aperture sight on the ladder, suitable for precision use at long range, the battle sight remained a standard open U-notch affair.

The M1917 by comparison has a generously sized opening that allows for quick target acquisition, even in situations of low light. Like anything new, this caused some controversy amongst both the troops of the American Expeditionary Force and the rifle demonstrators themselves. Besides the nature of the bolt, Capt. Morris noted that two of the most frequent complaints he heard were the lack of a windage gauge, and “the open field around the aperture in the rear sight.”

For the men under his instruction, Capt. Munn had a ready answer for the former complaint and stated that “It was readily realized that windage adjustment would be useless [and] small peep sights a hindrance. The ‘Hun’ will not wait for the Yankee to prepare for his execution,” and that “Expert riflemen who have been engaged by the Government to test the accuracy and rapidity of the 1903 and 1917 rifles, have become equally proficient in the latter model.”

The long-range champion Capt. Preussner likewise included in his instruction that, “The advantages of an aperture sight over an open sight is no longer questioned by the best marksmen” – an insight he was uniquely qualified to give.

The sling and stacking swivels are offset to the right — a vestigial holdover from the Pattern 14, which featured a left side volley sight.

The sling and stacking swivels are offset to the right — a vestigial holdover from the Pattern 14, which featured a left side volley sight.

Others received questions regarding smaller components. Capt. W.B. Porter, working out of Camp Dix, N.J., inquired as to “why the hinge of these [sling] swivels was not centered… as its present one-sided shape naturally produces a cant in the position of the rifle.” The offset sling and stacking swivels on the M1917 do seem particularly strange, until one realizes that they are a vestige of the Pattern 14 design, which featured a left-side mounted volley sight that necessitated the sling be kept well out of the way.

While Capt. Porter likely knew the original reason for the offset, he failed to see why during the re-design this wasn’t “corrected.” One can guess that it was easier and cheaper to just keep producing the now unnecessarily offset swivels, so it was retained to the great puzzlement of the troops and later collectors alike.

Another gripe encountered was the lack of a magazine cutoff like the one found on the M1903. While of dubious combat effectiveness, cutoffs have the pleasant effect of making the rifle much easier to use during the manual of arms, inspections and other training, as the bolt can be run freely back and forth without being stopped by the follower.

Capt. Preussner instructed his students that they were absent for a reason, “in that a man can not become confused and forget he has a magazine full of cartridges.”

To ease the manual of arms, soldiers were to be issued with follower depressors, although these often seemed to be in short supply. The same effect can be achieved with a strategically placed coin, a trick that many a Doughboys surely made use of.

At least one soldier got lucky, however, as Capt. Preussner “found a follower of the British model assembled in Eddystone rifle No. 111397 and it was a source of gratification to the owner for it did not lock his bolt open when it was opened for “inspection arms”.

Without a magazine cutoff, the follower always prevents the bolt from going forward on an empty magazine. Special follower depressors were issued but seemed too often be in short supply.

Without a magazine cutoff, the follower always prevents the bolt from going forward on an empty magazine. Special follower depressors were issued but seemed too often be in short supply.

Raw Industrial Might

Another question that the rifle demonstrators had to answer was “why?”. Why were troops being primarily armed with foreign designed rifles, when there was a perfectly good all-American rifle in the M1903? Lt. Askins sent word from Camp Humphreys, Va., that “… the query constantly meets me as to why the Model 17 was substituted for the Springfield.” While he found that newly enlisted soldiers were typically satisfied when told that they were receiving the best rifle obtainable, the more veteran soldiers were not so easily pacified.

He wrote Thompson, asking “What was the capacity of the Springfield factory at the beginning of the War? What is its capacity today? How many rifles can be turned out daily or weekly by the various Model 17 plants?”

Whether Lt. Askins ever received the exact data he requested, the numbers certainly supported the rifle demonstrators’ assertion that M1917 production far outstripped that of the M1903.

At the start of the war, according to Gen. Crozier, Springfield was actually not producing any rifles – instead the output was put completely over to spare parts (although 587,468 rifles were on hand at the start of hostilities). Between April and December 1917, Gen. Crozier estimated that Springfield would be able to produce 800 rifles per day, in addition to necessary spare parts. Rock Island Arsenal, the other producer of M1903s, was trickling out 25 rifles per day in April of 1917, with an estimated 400 per day by December.

In comparison, during the first week of April 1918, the Eddystone factory produced between 1,500 and 3,700 M1917s a day, and all three manufacturers combined to produce 32,213 rifles in that single week.

A June 1919 report from the Ordnance office indicates that while 327,157 M1903s were produced between April 1917 and November 1918, a staggering 2,295,390 M1917s were manufactured during the same period – outpacing the M1903 rate of production to a tune of 7:1, and leading to fully two-thirds of the American Expeditionary Force being armed with the M1917 on the armistice.

Developing a Course of Instruction

While the rifle demonstrators seem to be given fairly wide latitude to design their course of instruction, a number seem to have developed fairly similar classes that addressed most of the burning questions that the men training to fill out the American Expeditionary Force had about the new rifle, as well as provide them the knowledge to properly use and care for it.

Capt. A.E. Clark of the National Guard submitted a 17-page summary of his lecture and demonstration he gave to the officers of the 341st Infantry at Camp Grant, Ill., on Feb. 8, 1918. After declaring the new rifle the “Soldier’s Best Friend,” he delved into the history of its development, a comparison to the M1903 and the importance of proper care being given to the rifle.

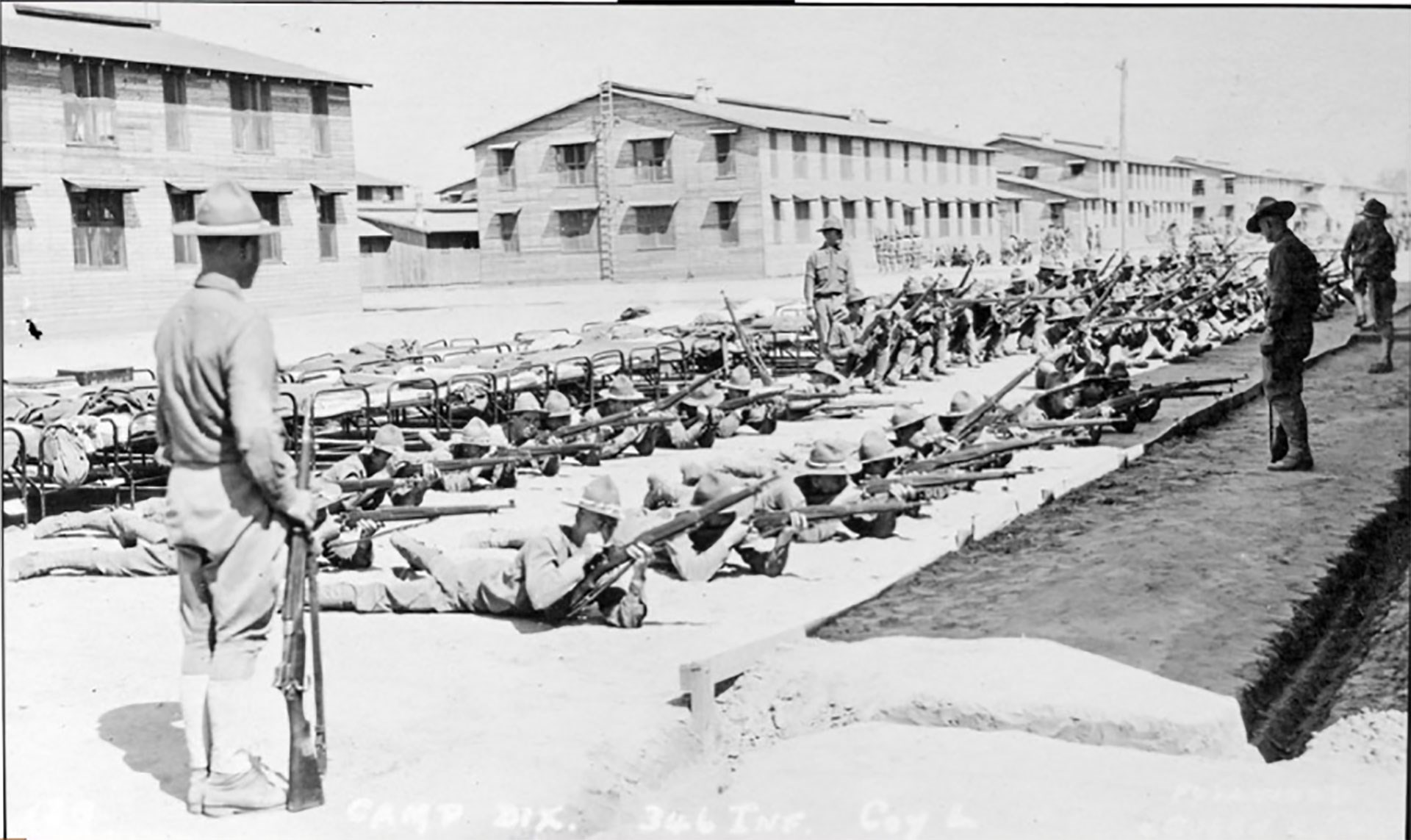

Soldiers undergo basic rifle training with the M1917 outside their barracks at Camp Dix, N.J.

Soldiers undergo basic rifle training with the M1917 outside their barracks at Camp Dix, N.J.

In the spring of 1918 both Capt. Preussner and Lieutenant Loos filed outlines of their standard classes, the contents of which shows these men took their duties seriously, and were doing their very best to ensure the men they instructed were going into battle with as much practical knowledge about the M1917 as possible.

The men assigned as rifle demonstrators were not ivory tower officers, ensconced in offices or their private billets. Instead, their duties were “naturally dirty and greasy” as described by Capt. Munn, and they frequently found themselves elbow deep in heavily greased rifle parts, or lying in the mud on the rifle range, in addition to their more standard classroom instruction.

Unexpected Issues

Unfortunately for the rifle demonstrators, they had to address some things beyond just the unique features of the new rifle.

One such problem, discovered upon uncrating brand-new rifles direct from the factory, were that some were arriving in a rusted state. Capt. Munn wrote that “A large number of […] ‘Eddystone’ rifles, January and February 1918 as issued to this Division, have been received in a frightfully rusted condition within the bore and receiver, likewise on the leaf sights.” He also noted that the rust actually appeared under the applied shipping grease, and that there was “considerable difficulty” in removing the rust on the rifles. Capt. W.B. Porter also reported similar issues with Eddystone rifles in March of 1918, although the problem does not appear to have been as severe as that experienced by Captain Munn.

Other rifles also arrived at Camp Travis, Texas, either not cosmolined or improperly cosmolined, and resulted in 346 Eddystone rifles of the 165th Depot Brigade to be classified as either “Rusty” or “Very Rusty”. Fortunately, identifying and tackling such issues was one of the stated aims of the rifle demonstrator program, and by April 1918 the Assistant Chief Inspector of the Eddystone Rifle Plant was assuring the Ordnance Department the greasing process was sufficiently modified and refined to ensure that “absolutely no difficulty will be encountered in the future from rust accumulation.”

The receiver on this March-April produced Eddystone made M1917 features a mottled finish loss to the original bluing. Perhaps due to the rust issues that plagued Eddystone rifles made during this time period.

The receiver on this March-April produced Eddystone made M1917 features a mottled finish loss to the original bluing. Perhaps due to the rust issues that plagued Eddystone rifles made during this time period.

As an aside, if you want to read a fascinating memorandum on the comparative approaches of brush vs. dipping grease application, and the appropriate consistency and heat of the grease in said dipping tanks, I encourage you to check out Archival Research Group, which has made these admittedly somewhat obscure documents available to people all over the world.

Other issues, duly reported on by various demonstrators, included a critical shortage of instruction manuals, parts interchangeability concerns, parts breakage (especially extractors), some parts needing re-fitting by troops, screws being center-punched (causing difficulty in disassembly, which was necessary to clear the grease), a shortage of spare parts, spare parts being provided with British nomenclatures, a lack of proper maintenance tool kits, lack of front sights, lack of front sight adjustment tools and lack of magazine-follower depressors.

One comical, although surely frustrating error, was reported by Capt. Munn who stated, “I received 100 #1917 pamphlets on U.S. Model 30 cal 1917 rifle this week […] Upon opening the package this morning I find they are imperfect. On page 51, there is an illustration and description of a radiator instead of description of repair parts of the 1917 rifle.”

They Too Become Enthusiastic About Them

With persistent effort however, demonstrators began to find success in convincing many men of the quality and effectiveness of the M1917. Lt. Loos, writing from Camp Custer, Mich., indicated in April 1918 that “Practically all the comments I hear now from officers of the Division are very favorable to the new rifle. Col. Allen, one of the famous shots of the country, in the course of a lecture to the School of Musketry commended the new rifle very highly, stating that in some respects it was better than Springfield and in other respect not quite as good and that the Springfield and the Model 1917 were the two best military rifles in the world. Maj. Harris, another rifleman of long experience and a member of the Infantry teams, speaks highly of the shooting qualities of the new rifle.”

In March 1918, 1st Lt. James Wallace, reporting from Camp Upton, N.Y., stated that while the men of the 77th Division were initially skeptical upon be re-equipped with M1917s, he found that “as soon as the Officers and men are shown the care of manufacture, and inspection methods, and the really excellent arm they have, they too become enthusiastic about it.” The men of the 77th Division would put their M1917s to hard use at the Battle of Château-Thierry just a few months later, as well as throughout the rest of the war.

The 77th Infantry Division on parade with their M1917s at Camp Upton, N.Y.

The 77th Infantry Division on parade with their M1917s at Camp Upton, N.Y.

After training with the men of the 367th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division, one of their experienced regular service field-grade officers reported to Lt. Wallace that “in his judgement the [M1917] met every requirement” and “spoke of the splendid success the regiment had had in training green troops to shoot with it.”

In addition, while he felt it not as well-balanced as the M1903, the M1917 “compared favorably with [the M1903] in every respect and in the matter of the location of rear sight and size of aperture, and battle sight that it was much to be preferred to the Springfield”.

While it would have been an impossible task to convince every man that was handed a M1917 of its superiority to all other rifles on the battlefield, it is evident that the rifle demonstrators truly believed in the quality of the rifle, and endeavored to instill a sense of confidence in the men to whom the M1917 was issued.

Overall, the rifle demonstrator program should be considered a success since a small number of Army officers were able to influence the training, competence and confidence of an enormous number of Doughboys newly equipped with the M1917.

On top of this, they were able to serve as the eyes and ears of the Ordnance Department and M1917 factories, reporting back issues and concerns so that they could be addressed as quickly as possible. While much attention is rightly paid to the battlefield heroics that took place overseas, great credit should also be given to the dedicated – and often highly experienced – men who remained stateside with the duty to arm, equip, educate and train the largest military force that North America had ever seen.

There they are !!!! N.S.F.W.