Some great Sailors who fought for the wrong side! Grumpy

Category: Soldiering

By Ismail Shakil

OTTAWA (Reuters) – General Jennie Carignan took over as Canada’s chief of the defense staff on Thursday in a ceremony that made her the first woman to command the country’s armed forces.

Trained as a military engineer, Carignan has commanded troops in Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iraq and Syria during her 35 years in the Canadian Army.

“I feel ready, poised and supported to take on this manifold challenge,” Carignan said at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

“Conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East, heightened tensions elsewhere around the world, climate change, increased demands on our personnel at home and abroad, and threats to our democratic values and institutions are but a few of the complex challenges we need to adapt to and counter,” Carignan said.

Carignan takes over from General Wayne Eyre, who served as the top military commander since 2021, at a time when Canada is aiming to increase defense spending and modernize its armed forces.

Last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced his government’s intention to reach NATO’s defense-spending target of 2% of GDP by 2032. Canada’s defense spending is expected to be 1.39% of GDP in the 2024-25 fiscal year, according to government projections.

The armed forces are struggling to meet recruitment goals and have been slow to replace outdated equipment.

Last November, the head of the navy said the service was in “a critical state” and might not be able to carry out its basic duties in 2024.

“We’re facing many internal challenges such as recruitment and retention,” Carignan said. “We know the challenges we face and what we need to do to address them.”

Trudeau, who called Carignan “a role model for all Canadians and for the world”, has pursued policies designed to boost gender equality since taking office in 2015.

In 2018, he appointed Brenda Lucki as the first female head of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The last two governors general, Canada’s official representative of the British monarchy, have been women. Trudeau named them both.

(Reporting by Ismail Shakil in Ottawa; Editing by Rod Nickel)

Navy SEAL Michael Monsoor was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in Iraq in 2006. He is one of seven Navy SEAL Medal of Honor recipients in history. Wikimedia Commons photo.

The United States Congress established the Medal of Honor during the early months of the American Civil War. The award’s first recipients were a group of six Union Army soldiers who earned it for carrying out a daring mission to sabotage a strategic Confederate rail line deep in enemy territory.

As the story goes, the so-called “Great Locomotive Chase” began on April 12, 1862, when a detachment of Union Army soldiers disguised in plain clothes boarded a passenger locomotive in Marietta, Georgia. Accompanied by a pair of civilian spies, including their leader, James Andrews, the men settled themselves at the rear of the train as it moved out of the station and headed north toward Tennessee.

All 20 members of the detachment who boarded the train (there were four others who didn’t make it) were volunteers. Their mission was to destroy as many bridges as possible along the Western and Atlantic Railroad — a vital Confederate supply line connecting Atlanta with Chattanooga.

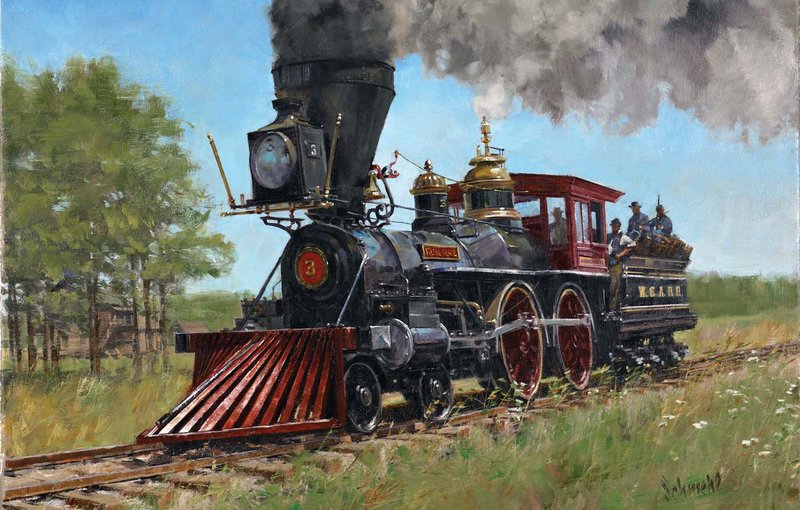

Union spy James Andrews and his handpicked team of saboteurs race toward Chattanooga aboard the stolen engine The General in modern artist Bradley Schmehl’s painting of the Great Locomotive Chase. Photo courtesy of artist Bradley Schmehl (www.bradleyschmehl.com).

Shortly after leaving Marietta, the train, called The General, eased to a stop in the town of Big Shanty. Around dawn, the conductor and most of his crew and passengers disembarked and headed to a nearby hotel for breakfast. Meanwhile, Andrews and his men, having exited on the opposite side of the train, disconnected the cab from the passenger cars and drove it out of the station.

The saboteurs made periodic stops as they chugged along toward Chattanooga, using tools they had stolen from some railroad repairmen to tear up rail lines, cut telegraph wires, and litter the tracks with railroad ties to obstruct the rebel troops pursuing them. Yet they didn’t manage to burn any bridges, as the task proved too time consuming to carry out without risking capture.

The General finally ran out of steam just south of Chattanooga. At that point, Andrews and his men abandoned the train and made a run for it. They were captured by Confederate soldiers several days later and sent before a judge on charges of “unlawful belligerency.”

All the men were convicted. Eight of them, including Andrews, were executed by hanging. The rest either managed to escape or became prisoners of war.

Heroism and Sacrifice

Tech Sgt. John Chapman was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions while serving as an Air Force Combat Controller in Afghanistan on March 4, 2002. Wikimedia Commons photo.

On March 25, 1863, six members of the detachment who had managed to make it back to the North appeared in Washington, DC, to become the first-ever recipients of the Medal of Honor. Years later, 13 of their comrades were also awarded the medal, bringing the total number of “Andrew’s Raiders” to earn the nation’s highest military honor to 19.

Since then, the number of Medal of Honor recipients has grown into the thousands, and yet the award retains its prestige. It is the US military’s highest decoration — intended to recognize “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty” — and the only one that must be personally approved by the president. In fact, living recipients are usually first notified that they will receive the reward in a phone call from the Commander in Chief himself.

In 1990, the United States Congress officially designated March 25 as National Medal of Honor Day. The federal holiday commemorates the “heroism and sacrifice of Medal of Honor recipients.” Congress chose March 25 because it marks the anniversary of the first medals being awarded.

Medal of Honor Recipients by Branch

A painting of US Coast Guard personnel evacuating US Marines from near Point Cruz on Guadalcanal under fire during the Second Battle of the Matanikau on Sept. 27, 1942. Douglas Munro is the only US coast guardsman to be awarded the Medal of Honor. Wikimedia Commons photo.

To date, according to the National Medal of Honor Museum database, approximately 3,516 individuals have earned the medal. 19 have earned it twice. The pantheon of recipients includes members of every US military branch except for Space Force.

The US Army, Navy, and Marine Corps account for the majority of Medal of Honor recipients. The Army boasts more than 2,400; the Navy, 749; and the Marines, 300. Nineteen airmen have received the award since the US Air Force became its own branch in 1947. The Coast Guard, which doesn’t typically participate in combat operations, has produced just one recipient: Signalman 1st Class Douglas Munro, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during World War II.

Fascinating Trivia About the Medal of Honor

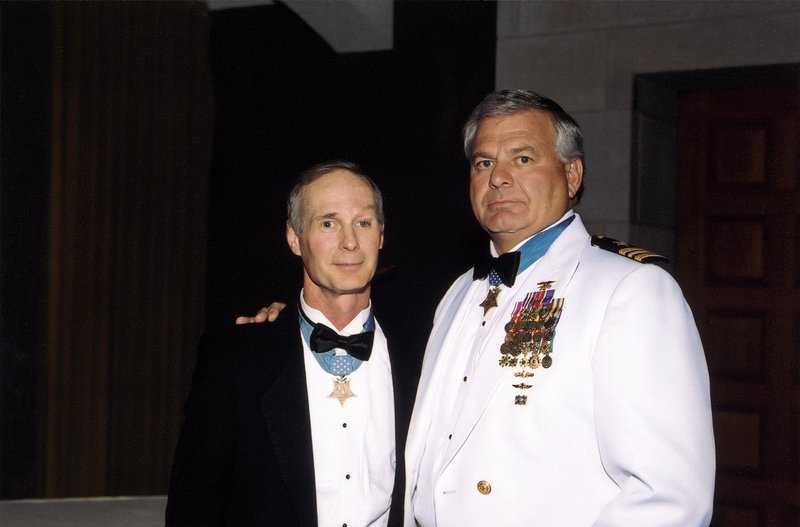

Medal of Honor recipients Navy SEAL Michael Thornton and Navy SEAL Tommy Norris at the American Academy of Achievement’s 2001 Banquet of the Golden Plate ceremonies in San Antonio, Texas. Photo courtesy of the Academy of Achievement.

- Medal of Honor recipient Pvt. Adam Paine was shot and killed by fellow Medal of Honor recipient Capt. Claron Windus. Paine had become an outlaw after the Civil War. Windus, a lawman, killed Paine while trying to arrest him.

- Three Medal of Honor recipients are credited with saving the life of another Medal of Honor recipient. Perhaps the most famous is Navy SEAL Mike Thornton, who earned the medal in Vietnam when he rescued Medal of Honor recipient Tommy Norris while their small commando team was engaged in an intense battle with a much larger enemy force.

- The list of Medal of Honor recipients includes four unidentified American service members. They lay buried at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and its three adjoining crypts at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Together, they are intended to represent “the soul of America and the supreme sacrifice of her heroic dead” in World War I, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.

- The list also includes five unidentified soldiers from France, Belgium, Italy, Romania, and Great Britain who all died fighting for the Allies in World War I and are buried overseas.

- 120 soldiers earned the Medal of Honor in the Civil War Battle of Vicksburg, 96 of them in the same day. It is believed that the battle accounts for the most Medals of Honor earned in a single engagement.

- In 2001, Theodore Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Battle of Kettle Hill during the Spanish-American War. He is the only US president to ever receive the medal.

The Story of the Youngest Medal of Honor Recipient

William “Willie” Johnston is the youngest Medal of Honor recipient in US military history. Wikimedia Commons photo.

The youngest person to earn the Medal of Honor was an 11-year-old drummer boy named William “Willie” Johnston. In 1861, Johnston’s father enlisted in the US Army in Vermont. Johnston followed suit and was assigned to D Company of the 3rd Vermont Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Johnston was issued a uniform and a drum. During the Civil War, drummers, who were typically adolescent boys, provided “drum calls” to signal actional commands. The loud beats of the drum were easier to hear over the sound of cannon and gunfire than the shouts of a commanding officer.

Johnston accompanied his unit to Virginia. He participated in a series of skirmishes fought between June 25 and July 1, 1862, called the Seven Days Battles.

When the Union Army was forced to retreat following its failed attempt to capture Richmond, many of its musicians abandoned their instruments to make a faster escape. But not Willie. In fact, he was the only drummer in his division to return to friendly lines with his instrument.

Upon learning of Johnston’s story, President Abraham Lincoln was so impressed by the drummer boy’s courage that he recommended him for the Medal of Honor. In 1863, at age 13, Willie received the medal.

The Only Female Medal of Honor Recipient

Mary Edwards Walker volunteered to treat Union soldiers wounded on the frontlines of Civil War battles. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

In the 1850s, Mary Edwards Walker was one of just two practicing female physicians in the entire United States. When the Civil War began, she volunteered to put her medical skills to work for the Union Army and was contracted as a field surgeon. She would be the only woman to serve in that role during the war, while as many as 10,000 women served as nurses.

In 1863, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas appointed Walker as the assistant surgeon for the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and she joined the unit in Tennessee. While traveling to Georgia, she was captured by Confederate soldiers and accused of being a spy. She spent four months as a prisoner of war before being released back to her unit.

Since she worked in contract positions during the war, she wasn’t officially a US military member. Still, Major Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and George Thomas deemed her contributions to the war effort worthy of the Medal of Honor and recommended her for the award. She received the medal in 1866.

Viet Cong booby traps were treacherous devices that destroyed and took countless lives. Read up on their history and impact on warfare.

During the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong (VC), a communist guerrilla force in South Vietnam, employed a variety of booby traps to counter the technological superiority of American and South Vietnamese forces.

These traps inflicted maximum damage on unsuspecting soldiers, leaving a lasting impact on the battlefield. In this layman’s history, we will explore the development, types, and impact of Viet Cong booby traps.

THE ORIGIN STORY OF VIET CONG BOOBY TRAPS

The origins of Viet Cong booby traps go back to guerrilla warfare, where a weaker force strategically targets and disrupts a stronger opponent. With limited resources and firepower, the Viet Cong needed alternative means to counter the American and South Vietnamese forces’ advanced technology and overwhelming military strength.

Necessity Breeds Innovation

The Viet Cong’s resourcefulness and adaptability were crucial in developing booby traps. Unable to match the firepower of their adversaries, they relied on inventive and low-cost methods to inflict damage and instill terror.

The need to defend their territory, disrupt enemy movements, and demoralize opposing forces fueled the innovation behind these traps.

A Viet Cong booby trap was about utilizing readily available local materials. Derived from bamboo, wooden stakes, and basic explosives, guerillas had easy access to materials. This approach allowed them to maximize their limited resources and create deadly devices without relying on external support.

Learning From Historical Precedents

The Viet Cong drew inspiration from historical precedents and existing knowledge of warfare, adapting and refining techniques used in previous conflicts. They incorporated elements of traditional booby traps employed in earlier conflicts, such as their war against the French, and from indigenous methods used in the region.

TYPES OF VIET CONG BOOBY TRAPS

Numerous types of Viet Cong booby traps were in circulation during the Vietnam War. While it is difficult to provide an exact count, given the vast range and variations, here are some of the most prominent types:

- Punji Pit Traps: These traps involved camouflaged pits dug into the ground, often with sharpened bamboo stakes or other spikes at the bottom, intended to impale or injure soldiers who fell into them.

- Tripwire Explosives: Tripwire-based traps utilized thin wires connected to explosives hidden nearby. When a soldier unknowingly triggered the wire by tripping over it, it would detonate the explosive, causing severe injuries or death.

- Bouncing Betty Mines: These mines were pressure-activated and launched into the air before detonating. Buried in the ground, they targeted the lower body of soldiers, causing devastating injuries and reducing the chances of survival.

- Toe-Popper Mines: These small, pressure-activated mines were typically buried just below the surface, designed to injure or disable soldiers. Stepping on them would trigger an explosion, inflicting severe damage to the victim’s foot or leg.

- Bamboo Whip Traps: Bamboo stakes, often tipped with poison, were bent and secured under tension. When triggered, the stakes would whip out, causing deep puncture wounds and potential infection due to the poison.

- Snake Traps: Containers or bamboo tubes were the primary tools to hold venomous snakes, each strategically placed to surprise and attack soldiers, causing panic and distraction.

- Grenade Traps: Hand grenades came with tripwires or other triggering mechanisms designed to explode when disturbed, injuring or killing anyone nearby.

- Punji Stick Traps: Similar to Punji pit traps, Punji stick traps involved concealed stakes or spikes, often coated with toxic substances, hidden in foliage or along trails to injure or infect soldiers.

- Rolling Log Traps: Guerillas positioned large logs to roll down hills or slopes upon triggering, aiming to crush or injure soldiers caught in their path.

- Booby-Trapped Ammo and Supplies: Viet Cong forces sometimes rig ammunition or other supplies to explode when picked up or used by enemy forces, causing unexpected casualties.

THE MENACING DAMAGE CAUSED BY VIET CONG BOOBY TRAPS

Soldiers caught in booby traps often suffered severe injuries, including loss of limbs, shrapnel wounds, and internal damage. The injuries inflicted by these traps could be debilitating, sometimes leading to long-term disabilities or even death.

Beyond the physical harm, Viet Cong booby traps had a significant psychological impact on soldiers. The constant fear of hidden dangers, the tension of moving through unfamiliar terrain, and the unpredictability of these traps created a pervasive sense of anxiety and vulnerability among troops.

Viet Cong booby traps profoundly impacted the course of the Vietnam War and left a lasting mark on military history. For one, they forced the American and South Vietnamese forces to adapt their strategies and tactics.

The hidden nature and widespread use of these traps necessitated changes in how troops moved through the terrain, increasing caution and the need for specialized training in identifying and neutralizing booby traps.

Viet Cong Booby Traps and Their Impact on Modern Warfare

Viet Cong booby traps also significantly influenced the evolution of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The lessons learned from the Vietnam War, including the effectiveness of concealed explosive devices, shaped the development of IEDs in subsequent conflicts. It profoundly impacted modern warfare, as IEDs became a significant threat in armed conflicts worldwide.

Ultimately, Viet Cong booby traps changed history by reshaping military strategies, highlighting the importance of psychological warfare, affecting civilian populations, influencing military training, and contributing to the evolution of explosive devices.

These traps left an indelible mark on the Vietnam War and influenced subsequent conflicts, emphasizing the need for adaptive and comprehensive approaches to unconventional warfare.

And then the Brigade Commander showed up!

And then the Brigade Commander showed up!

|

Joe Ronnie Hooper

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | August 8, 1938 Piedmont, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | May 6, 1979 (aged 40) Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1956–1959 (USN) 1960–1978 (USA) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War (WIA) |

| Awards | |

Joe Ronnie Hooper (August 8, 1938 – May 6, 1979) was an American who served in both the United States Navy and United States Army where he finished his career there as a captain. He earned the Medal of Honor while serving as an army staff sergeant on February 21, 1968, during the Vietnam War. He was one of the most decorated U.S. soldiers of the war and was wounded in action eight times.

Early life and education[edit]

Hooper was born on August 8, 1938, in Piedmont, South Carolina. His family moved when he was a child to Moses Lake, Washington where he attended Moses Lake High School.

Career[edit]

Hooper enlisted in the United States Navy in December 1956. After graduation from boot camp at San Diego, California he served as an Airman aboard USS Wasp and USS Hancock. He was honorably discharged in July 1959, shortly after being advanced to petty officer third class.

U.S. Army

Hooper enlisted in the United States Army in May 1960 as a private first class, and attended Basic Training at Fort Ord, California. After graduation, he volunteered for Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, then was assigned to Company C, 1st Airborne Battle Group, 325th Infantry,[1] 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and was promoted to corporal during this assignment.

He served a tour of duty in South Korea with the 20th Infantry in October 1961, and shortly after arriving, he was promoted to sergeant and was made a squad leader. He left Korea in November 1963, and was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas for a year as a squad leader, then became a squad leader with Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 502nd Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

He was promoted to staff sergeant in September 1966, and volunteered for service in South Vietnam. Instead, he was assigned as a platoon sergeant in Panama with the 3rd Battalion (Airborne), 508th Infantry, first with HQ Company and later with Company B.

Hooper could not stay out of trouble, and suffered several Article 15 hearings, then was reduced to the rank of corporal in July 1967. He was promoted once again to sergeant in October 1967, and was assigned to Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, and deployed with the division to South Vietnam in December as a squad leader.

During his tour of duty with Delta Company (Delta Raiders), 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, he was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on February 21, 1968, during the Battle of Huế.[2]

He returned from South Vietnam, and was discharged in June 1968. He re-enlisted in the Army the following September, and served as a public relations specialist. On March 7, 1969, he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon during a ceremony in the White House. From July 1969 to August 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with the 3rd Battalion, 5th Infantry in Panama.

He managed to finagle a second tour in South Vietnam; from April to June 1970, he served as a pathfinder with the 101st Aviation Group, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), and from June to December 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile).

In December 1970, he received a direct commission to second lieutenant and served as a platoon leader with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) until April 1971.

Upon his return to the United States, he attended the Infantry Officer Basic Course at Fort Benning, and was assigned as an instructor at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Despite wanting to serve twenty years in the Army, Hooper was made to retire in February 1974 as a first lieutenant, mainly because he only completed a handful of college courses beyond his GED.

As soon as he was released from active duty, he joined a unit of the Army Reserve’s 12th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in Washington as a Company Executive Officer. In February 1976, he transferred to the 104th Division (Training), also based in Washington. He was promoted to captain in March 1977. He attended drills intermittently, and was separated from the service in September 1978.

For his service in Vietnam, the U.S. Army also awarded Hooper two Silver Stars, six Bronze Stars, eight Purple Hearts, the Presidential Unit Citation, the Vietnam Service Medal with six campaign stars, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

He is credited with 115 enemy killed in ground combat, 22 of which occurred on February 21, 1968. He became one of the most-decorated soldiers in the Vietnam War,[2] and was one of three soldiers wounded in action eight times in the war.

Later life and death

According to rumors, he was distressed by the anti-war politics of the time, and compensated with excessive drinking which contributed to his death.[3] He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Louisville, Kentucky on May 6, 1979, at the age of 40.

Hooper is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 46, adjacent to the Memorial Amphitheater.

Military awards

Hooper’s military decorations and awards include:

|

|||

| Combat Infantryman Badge | |||||||||||

| Medal of Honor | Silver Star w/ 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

||||||||||

| Bronze Star w/ Valor device and 1 silver oak leaf cluster |

Purple Heart w/ 1 silver and 2 bronze oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal w/ 4 bronze oak leaf clusters |

|||||||||

| Army Commendation Medal w/ Valor device and 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

Army Good Conduct Medal w/ 3 bronze Good conduct loops |

Navy Good Conduct Medal | |||||||||

| National Defense Service Medal | Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal | Vietnam Service Medal w/ 1 silver and 1 bronze campaign stars |

|||||||||

| Vietnam Cross of Gallantry w/ Palm |

Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal | Navy Pistol Marksmanship Ribbon w/ “E” Device |

|||||||||

| Army Presidential Unit Citation | ||

| Vietnam Presidential Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Civil Actions Unit Citation |

|

|

|

| Master Parachutist Badge | Expert Marksmanship Badge w/ 1 weapon bar |

Vietnam Parachutist Badge |

Medal of Honor citation

Medal of Honor

{{quote|Rank and organization: Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, Company D, 2d Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. Place and date: Near Huế, Republic of Vietnam, February 21, 1968. Entered service at: Los Angeles, Calif. Born: August 8, 1938, Piedmont, S.C.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Staff Sergeant (then Sgt.) Hooper, U.S. Army, distinguished himself while serving as squad leader with Company D. Company D was assaulting a heavily defended enemy position along a river bank when it encountered a withering hail of fire from rockets, machine guns and automatic weapons. S/Sgt. Hooper rallied several men and stormed across the river, overrunning several bunkers on the opposite shore.

Thus inspired, the rest of the company moved to the attack. With utter disregard for his own safety, he moved out under the intense fire again and pulled back the wounded, moving them to safety. During this act S/Sgt. Hooper was seriously wounded, but he refused medical aid and returned to his men. With the relentless enemy fire disrupting the attack, he single-handedly stormed 3 enemy bunkers, destroying them with hand grenade and rifle fire, and shot 2 enemy soldiers who had attacked and wounded the Chaplain. Leading his men forward in a sweep of the area, S/Sgt. Hooper destroyed 3 buildings housing enemy riflemen.

At this point he was attacked by a North Vietnamese officer whom he fatally wounded with his bayonet. Finding his men under heavy fire from a house to the front, he proceeded alone to the building, killing its occupants with rifle fire and grenades.

By now his initial body wound had been compounded by grenade fragments, yet despite the multiple wounds and loss of blood, he continued to lead his men against the intense enemy fire. As his squad reached the final line of enemy resistance, it received devastating fire from 4 bunkers in line on its left flank. S/Sgt. Hooper gathered several hand grenades and raced down a small trench which ran the length of the bunker line, tossing grenades into each bunker as he passed by, killing all but 2 of the occupants.

With these positions destroyed, he concentrated on the last bunkers facing his men, destroying the first with an incendiary grenade and neutralizing 2 more by rifle fire. He then raced across an open field, still under enemy fire, to rescue a wounded man who was trapped in a trench.

Upon reaching the man, he was faced by an armed enemy soldier whom he killed with a pistol. Moving his comrade to safety and returning to his men, he neutralized the final pocket of enemy resistance by fatally wounding 3 North Vietnamese officers with rifle fire. S/Sgt. Hooper then established a final line and reorganized his men, not accepting treatment until this was accomplished and not consenting to evacuation until the following morning.

His supreme valor, inspiring leadership and heroic self-sacrifice were directly responsible for the company’s success and provided a lasting example in personal courage for every man on the field. S/Sgt. Hooper’s actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Army.

———————————————————————————— What a Stud!!! Grumpy