Category: Leadership of the highest kind

|

Joe Ronnie Hooper

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | August 8, 1938 Piedmont, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | May 6, 1979 (aged 40) Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1956–1959 (USN) 1960–1978 (USA) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War (WIA) |

| Awards | |

Joe Ronnie Hooper (August 8, 1938 – May 6, 1979) was an American who served in both the United States Navy and United States Army where he finished his career there as a captain. He earned the Medal of Honor while serving as an army staff sergeant on February 21, 1968, during the Vietnam War. He was one of the most decorated U.S. soldiers of the war and was wounded in action eight times.

Early life and education[edit]

Hooper was born on August 8, 1938, in Piedmont, South Carolina. His family moved when he was a child to Moses Lake, Washington where he attended Moses Lake High School.

Career[edit]

Hooper enlisted in the United States Navy in December 1956. After graduation from boot camp at San Diego, California he served as an Airman aboard USS Wasp and USS Hancock. He was honorably discharged in July 1959, shortly after being advanced to petty officer third class.

U.S. Army

Hooper enlisted in the United States Army in May 1960 as a private first class, and attended Basic Training at Fort Ord, California. After graduation, he volunteered for Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, then was assigned to Company C, 1st Airborne Battle Group, 325th Infantry,[1] 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and was promoted to corporal during this assignment.

He served a tour of duty in South Korea with the 20th Infantry in October 1961, and shortly after arriving, he was promoted to sergeant and was made a squad leader. He left Korea in November 1963, and was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas for a year as a squad leader, then became a squad leader with Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 502nd Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

He was promoted to staff sergeant in September 1966, and volunteered for service in South Vietnam. Instead, he was assigned as a platoon sergeant in Panama with the 3rd Battalion (Airborne), 508th Infantry, first with HQ Company and later with Company B.

Hooper could not stay out of trouble, and suffered several Article 15 hearings, then was reduced to the rank of corporal in July 1967. He was promoted once again to sergeant in October 1967, and was assigned to Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, and deployed with the division to South Vietnam in December as a squad leader.

During his tour of duty with Delta Company (Delta Raiders), 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Airborne Infantry, he was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on February 21, 1968, during the Battle of Huế.[2]

He returned from South Vietnam, and was discharged in June 1968. He re-enlisted in the Army the following September, and served as a public relations specialist. On March 7, 1969, he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon during a ceremony in the White House. From July 1969 to August 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with the 3rd Battalion, 5th Infantry in Panama.

He managed to finagle a second tour in South Vietnam; from April to June 1970, he served as a pathfinder with the 101st Aviation Group, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), and from June to December 1970, he served as a platoon sergeant with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile).

In December 1970, he received a direct commission to second lieutenant and served as a platoon leader with Company A, 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) until April 1971.

Upon his return to the United States, he attended the Infantry Officer Basic Course at Fort Benning, and was assigned as an instructor at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Despite wanting to serve twenty years in the Army, Hooper was made to retire in February 1974 as a first lieutenant, mainly because he only completed a handful of college courses beyond his GED.

As soon as he was released from active duty, he joined a unit of the Army Reserve’s 12th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in Washington as a Company Executive Officer. In February 1976, he transferred to the 104th Division (Training), also based in Washington. He was promoted to captain in March 1977. He attended drills intermittently, and was separated from the service in September 1978.

For his service in Vietnam, the U.S. Army also awarded Hooper two Silver Stars, six Bronze Stars, eight Purple Hearts, the Presidential Unit Citation, the Vietnam Service Medal with six campaign stars, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

He is credited with 115 enemy killed in ground combat, 22 of which occurred on February 21, 1968. He became one of the most-decorated soldiers in the Vietnam War,[2] and was one of three soldiers wounded in action eight times in the war.

Later life and death

According to rumors, he was distressed by the anti-war politics of the time, and compensated with excessive drinking which contributed to his death.[3] He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Louisville, Kentucky on May 6, 1979, at the age of 40.

Hooper is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 46, adjacent to the Memorial Amphitheater.

Military awards

Hooper’s military decorations and awards include:

|

|||

| Combat Infantryman Badge | |||||||||||

| Medal of Honor | Silver Star w/ 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

||||||||||

| Bronze Star w/ Valor device and 1 silver oak leaf cluster |

Purple Heart w/ 1 silver and 2 bronze oak leaf clusters |

Air Medal w/ 4 bronze oak leaf clusters |

|||||||||

| Army Commendation Medal w/ Valor device and 1 bronze oak leaf cluster |

Army Good Conduct Medal w/ 3 bronze Good conduct loops |

Navy Good Conduct Medal | |||||||||

| National Defense Service Medal | Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal | Vietnam Service Medal w/ 1 silver and 1 bronze campaign stars |

|||||||||

| Vietnam Cross of Gallantry w/ Palm |

Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal | Navy Pistol Marksmanship Ribbon w/ “E” Device |

|||||||||

| Army Presidential Unit Citation | ||

| Vietnam Presidential Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Civil Actions Unit Citation |

|

|

|

| Master Parachutist Badge | Expert Marksmanship Badge w/ 1 weapon bar |

Vietnam Parachutist Badge |

Medal of Honor citation

Medal of Honor

{{quote|Rank and organization: Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, Company D, 2d Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. Place and date: Near Huế, Republic of Vietnam, February 21, 1968. Entered service at: Los Angeles, Calif. Born: August 8, 1938, Piedmont, S.C.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Staff Sergeant (then Sgt.) Hooper, U.S. Army, distinguished himself while serving as squad leader with Company D. Company D was assaulting a heavily defended enemy position along a river bank when it encountered a withering hail of fire from rockets, machine guns and automatic weapons. S/Sgt. Hooper rallied several men and stormed across the river, overrunning several bunkers on the opposite shore.

Thus inspired, the rest of the company moved to the attack. With utter disregard for his own safety, he moved out under the intense fire again and pulled back the wounded, moving them to safety. During this act S/Sgt. Hooper was seriously wounded, but he refused medical aid and returned to his men. With the relentless enemy fire disrupting the attack, he single-handedly stormed 3 enemy bunkers, destroying them with hand grenade and rifle fire, and shot 2 enemy soldiers who had attacked and wounded the Chaplain. Leading his men forward in a sweep of the area, S/Sgt. Hooper destroyed 3 buildings housing enemy riflemen.

At this point he was attacked by a North Vietnamese officer whom he fatally wounded with his bayonet. Finding his men under heavy fire from a house to the front, he proceeded alone to the building, killing its occupants with rifle fire and grenades.

By now his initial body wound had been compounded by grenade fragments, yet despite the multiple wounds and loss of blood, he continued to lead his men against the intense enemy fire. As his squad reached the final line of enemy resistance, it received devastating fire from 4 bunkers in line on its left flank. S/Sgt. Hooper gathered several hand grenades and raced down a small trench which ran the length of the bunker line, tossing grenades into each bunker as he passed by, killing all but 2 of the occupants.

With these positions destroyed, he concentrated on the last bunkers facing his men, destroying the first with an incendiary grenade and neutralizing 2 more by rifle fire. He then raced across an open field, still under enemy fire, to rescue a wounded man who was trapped in a trench.

Upon reaching the man, he was faced by an armed enemy soldier whom he killed with a pistol. Moving his comrade to safety and returning to his men, he neutralized the final pocket of enemy resistance by fatally wounding 3 North Vietnamese officers with rifle fire. S/Sgt. Hooper then established a final line and reorganized his men, not accepting treatment until this was accomplished and not consenting to evacuation until the following morning.

His supreme valor, inspiring leadership and heroic self-sacrifice were directly responsible for the company’s success and provided a lasting example in personal courage for every man on the field. S/Sgt. Hooper’s actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Army.

———————————————————————————— What a Stud!!! Grumpy

The Medal of Honor is instantly recognized as our nation’s highest award for heroism. The familiar words, “Above and beyond the call of duty” are etched into every child’s memory as dreams of battlefield gallantry flicker across their thoughts and deeds while engaged in playground antics. Few know, however, that while the Medal of Honor was instituted in March of 1863, we had other ways of recognizing gallantry that date back to the American Revolution.

The Medal of Honor is instantly recognized as our nation’s highest award for heroism. The familiar words, “Above and beyond the call of duty” are etched into every child’s memory as dreams of battlefield gallantry flicker across their thoughts and deeds while engaged in playground antics. Few know, however, that while the Medal of Honor was instituted in March of 1863, we had other ways of recognizing gallantry that date back to the American Revolution.

In August of 1782, Gen. Washington wrote: “The General … directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with a due reward.” From that directive, we know of three “Purple Hearts for Military Merit” that were awarded to soldiers of the Continental Line and then the award fell into disuse and was eventually revived in 1932 as an award for being wounded in combat.

At the close of the American Revolution in 1781, Congress authorized the purchase and presentation of 15 swords to be made in Paris and inscribed with the thanks of Congress to the recipient—who had been nominated by Gen. Washington for superior service and gallantry. Eight of these swords are known to have survived.

During the War of 1812, Congress similarly presented 27 swords to those who had displayed gallantry at the Battle of Lake Erie. Eight are known to still exist today.

In another example, which is the only time Congress has presented an actual firearm to a soldier for heroism, at the Battle of Plattsburgh, N.Y., in 1814, 17 young men enlisted to help defend the city and received inscribed Hall’s rifles with personalized plaques that highlighted their service. Ten of these are accounted for today.

In March of 1863, six Medals of Honor were awarded at the War Dept. to the surviving soldiers who had taken part in the great locomotive chase later immortalized by Buster Keaton in the 1926 film “The General.” Inscriptions on the back read, “The Congress to …” and then the name, rank and location of the event were engraved upon the first medals given for valor in our military history.

Today, the Medal of Honor is our nation’s most-revered symbol of courage and gallantry. More than 3,000 have been earned since the Civil War, and those who survive to receive the award are held in high esteem for the rest of their lives.

Through the generosity of Norm Flayderman, Jack Lewis and Marvin Applewhite, the NRA National Firearms Museum has four original Medals of Honor in the collection. They are currently on exhibit, along with other symbols of valor that predate the Civil War.

Through the generosity of John McMurray, Craig Bell and Alan Boyd, of the American Society of Arms Collectors, the National Firearms Museum is pleased to announce the opening of Symbols of Valor, a collection of two of the Revolution’s presentation swords, two Lake Erie swords, one Plattsburgh Hall’s rifle and five Medals of Honor.

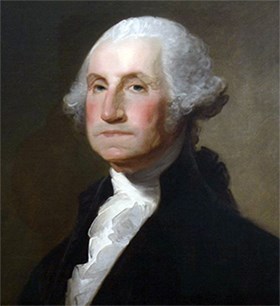

The exhibit is displayed with an original oil painting by Gilbert and Jane Stuart of George Washington, recently donated by the Estate of Doc Thurston of Charlotte, N.C.

———————————————————————————— In all my time in the Army. I have only met and promptly saluted one MOH man. Which should tell you that they are the elite of the elite of our Warriors! Grumpy

Field Marshal Rommel was a formidable foe. Here’s what America learned from him.

Editor’s Note: For today’s #ThrowbackThursday, we’re examining the lessons the Allied powers learned in World War II from one of America’s most formidable enemies at the time.

Arguably the greatest general that Germany produced during WWII was Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), The Desert Fox. A career soldier, he fought during both World Wars, and became so revered for his tactical leadership skills and aggressive battlefield style that some Allied forces began to believe he was superhuman. To that point, the British Army Commander-in-Chief C.J. Auchinleck, issued the following order to his officers:

There exists a real danger that our friend Rommel is becoming a kind of magician or bogey-man to our troops, who are talking far too much about him. He is by no means a superman, although he is undoubtedly very energetic and able.

Even if he were a superman, it would still be highly undesirable that our men should credit him with supernatural powers. I wish you to dispel by all possible means the idea that Rommel represents something more than an ordinary German general.

The important thing now is to see that we do not always talk of Rommel when we mean the enemy in Libya. We must refer to “the Germans” or “the Axis powers” or “the enemy” and not always keep harping on Rommel. Please ensure that this order is put into immediate effect, and impress up all commanders that, from a psychological point of view, it is a matter of highest importance.

No, Rommel was not superhuman, but he did have what the Germans called (big-word warning) Fingerspitzengefuhl, an innate sixth sense of what the enemy was about to do. For instance, a German general, Fritz Bayerlein, Rommel’s Chief-of-Staff at the time, relates the following two anecdotes.

“We were at the headquarters of the Afrika Korps…when suddenly Rommel turned to me and said, ‘Bayerlein, I would advise you to get out of this [location]: I don’t like it.’ An hour later the headquarters were unexpectedly attacked and overrun.”

Bayerlein continues, “That same afternoon, we were standing together when he [Rommel] said, ‘Let’s move a couple of hundred yards to a flank, I think we are going to get shelled here.’ One bit of desert was just the same as another, but five minutes after we had moved, the shells were falling exactly where we had been standing. Everyone…who fought with Rommel in either war will tell you similar stories.”

Rommel also had the ability to quickly size up a battle in progress, and the decision-making skills to then seize the opportunity to attack when one presented itself. Consequently, he earned a reputation for, at times, making rash decisions, but those decisions seemed to pay off for him and his armies more times than not.

A trait that endeared Rommel to his vanguard troops was that he “led from the front,” spending nearly as much time with the frontline, everyday soldier as he did with his officers back at headquarters. As a result, his soldiers were willing to follow him anywhere.

Another characteristic that helped make Rommel the military legend he became was that he was constantly learning, not only from his victories, but also his defeats—especially his defeats, which seemed to haunt him. And he was open to new ideas, new equipment, new weapons, anything that would make his armies more efficient and in turn, more successful.

For example, Rommel did not invent blitzkrieg—a highly mobile style of warfare employing armored, motorized forces—but he and his 7th Panzer Division of tanks certainly perfected it in France during 1940. Later in the war, his Afrika Korps then continued using the technique in the deserts of North Africa to win battle after battle.

Rommel had always been a prolific writer, and following his time in Africa he authored a paper titled The Rules of Desert Warfare, the small portions below being just a few of the more interesting excerpts from the six-page document.

- The tank force is the backbone of the motorized army. Everything turns on the tanks, the other formations are mere ancillaries. War of attrition against the enemy tank units must, therefore, be carried on as far as possible by one’s own tank destruction units…[they] must deal the last blow.

- Results of reconnaissance must reach the commander in the shortest possible time, and he must then make immediate decisions and put them into effect as quickly as possible. Speed of reaction in Command decisions decides the battle. It is, therefore, essential that commanders of motorized forces should be as near as possible to their troops and in the closest signal communication with them.

- It is my experience that bold decisions give the best promise of success. One must differentiate between operational and tactical boldness and a military gamble. A bold operation is one which has no more than a chance of success but which, in case of failure, leaves one with sufficient forces in hand to be able to cope with any situation. A gamble, on the other hand, is an operation which can lead either to victory or to the destruction of one’s own forces. Any compromise is bad.

- One of the first lessons which I drew from my experiences of motorized warfare was that speed of operation and quick reaction of the Command were the decisive factors. The troops must be able to operate at the highest speed and in complete coordination. One must not be satisfied here with any normal average but must always endeavor to obtain the maximum performance, for the side which makes the greater effort is the faster, and the faster wins the battle. Officers and NCOs must, therefore, constantly train their troops with this in view.

- In my opinion, the duties of the Commander-in-Chief are not limited to his staff work. He must also take an interest in the details of Command and frequently busy himself in the front line.

- The Commander-in-Chief must have contact with his troops. He must be able to feel and think with them. The soldier must have confidence in him. In this connection there is one cardinal principle to remember: one must never simulate a feeling for the troops which in fact one does not have. The ordinary soldier has a surprisingly good nose for what is genuine and what is fake.

In the WWII movie Patton, released in 1970, actor George C. Scott portrays the brash and flamboyant American General George S. Patton. Near the end of the movie, after Patton and his army have defeated Rommel and his troops, Patton shouts loudly across the battlefield in victory, “Rommel, you magnificent b______, I read your book!”

The book he was referring to was Rommel’s Infanterie Greift An (Infantry Attacks). Published in 1937, it chronicles his experiences during World War I. If you’d care to read it, the treatise will give you a look into the mind of one of the greatest tactical military geniuses of the 20th Century. The Rommel Papers, edited by B. H. Liddell Hart and published in 1953, is also highly recommended, relating Rommel’s WWII experiences in his own words.