Category: This great Nation & Its People

CHICAGO — Chicago native Matthew Hayes reportedly defied all odds this week by not being shot.

Experts had expected Hayes to be shot no less than six times while going out for pizza, but he surprised everyone by coming away unscathed.

“Wow, I guess I’m totally fine,” said Hayes. “What a surprise.”

In 2025 alone, there have been over 600 shootings resulting in approximately 188 deaths. In light of these statistics, experts are convinced that Hayes must be some sort of superhero impervious to bullets like Superman. “Hayes is a statistical anomaly,” said Dr. Gerald Rammings, a statistician for the University of Chicago. “No one can survive Chicago.”

Hayes has previously said that a hot pie from Lou Malnati’s Pizzeria was worth dying for, but now that he’s alive, the pizza doesn’t seem to mean as much. “It was just too easy,” he said. “I feel like I cheated death.”

At publishing time, Matthew Hayes had been rushed to the hospital after being shot while going out for dessert.

Jonny Kim in a high-altitude pressure suit worn in the WB-57 aircraft, which is capable of flying at altitudes over 60,000 feet. Photo by Norah Moran, courtesy of NASA/Wikimedia Commons.

If there really were an award for the Most Interesting Man in the World, 39-year-old Jonny Kim would be a top contender. He’s a Navy SEAL, a medical doctor, an aviator, and a NASA astronaut. His successes are even more remarkable for all the obstacles he had to overcome to achieve them. As the strongest steel is forged in the hottest fires, Kim was shaped into the extraordinary man he is today by circumstances that would have broken most people.

A Family Tragedy

In Kim’s telling, his uncommon drive is a byproduct of a tragic indicent that occured when he was 16 years old. One night, in February 2002, Kim’s alcoholic father came home drunk and brandishing a gun. According to a version of the story Kim recounted years later on the Jocko Podcast, his father attacked him with pepper spray before proceeding to beat his mother with the pistol. When Kim tried to intervene again, his father struck him in the head with a dumbbell.

Kim recalled that, despite being barely conscious, he pleaded with his father not to kill him and his mother. In a stroke of uncharacteristic mercy, his father ceased his assault, took the gun, and fled the house — or so they thought. When police arrived, they found him barricaded inside the attic. A brief stand-off ensued and the officers shot Kim’s father, wounding him fatally.

In his interview with Jocko Willink, Kim said the events of that night changed him on a fundamental level.

“It became the benchmark for me to do so many more things in my life I never thought possible,” he said. “Standing up to someone who was threatening to kill you — and who you loved the most — liberated me. It taught me I’m not the scared little boy I thought I was. I can do these things. I can be a part of something bigger than myself.”

Navy SEAL

Kim first learned about the Navy SEALs from a childhood friend. Determined to never again feel the fear and helplessness he felt the night his father was killed, Kim was drawn to the SEALs’ rigorous training, the profound sense of camraderie, and the opportunity to protect others. Furthermore, the Navy offered an escape from his tumultuous childhood in Los Angeles.

In 2002, Kim enlisted in the Navy as a hospital corpsman. Upon completing Navy bootcamp, he reported to Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training with BUD/S class 247. After completing the notoriously brutal course, he reported to Navy Special Warfare Group 3, aka SEAL Team Three, in Little Creek, Virginia.

As a SEAL during the early days of the Global War on Terror, Kim saw action on the front lines. He deployed twice to the Middle East. In Iraq, he conducted more than 100 combat missions, including in the insurgent strongholds of Ramadi and Sadr City. Over the course of his two tours, he served as a combat medic, sniper, navigator, and point man. During the fight for Ramadi, he distinguished himself by repeatedly braving enemy fire in order to drag wounded Iraqi allies to safety, receiving a Silver Star.

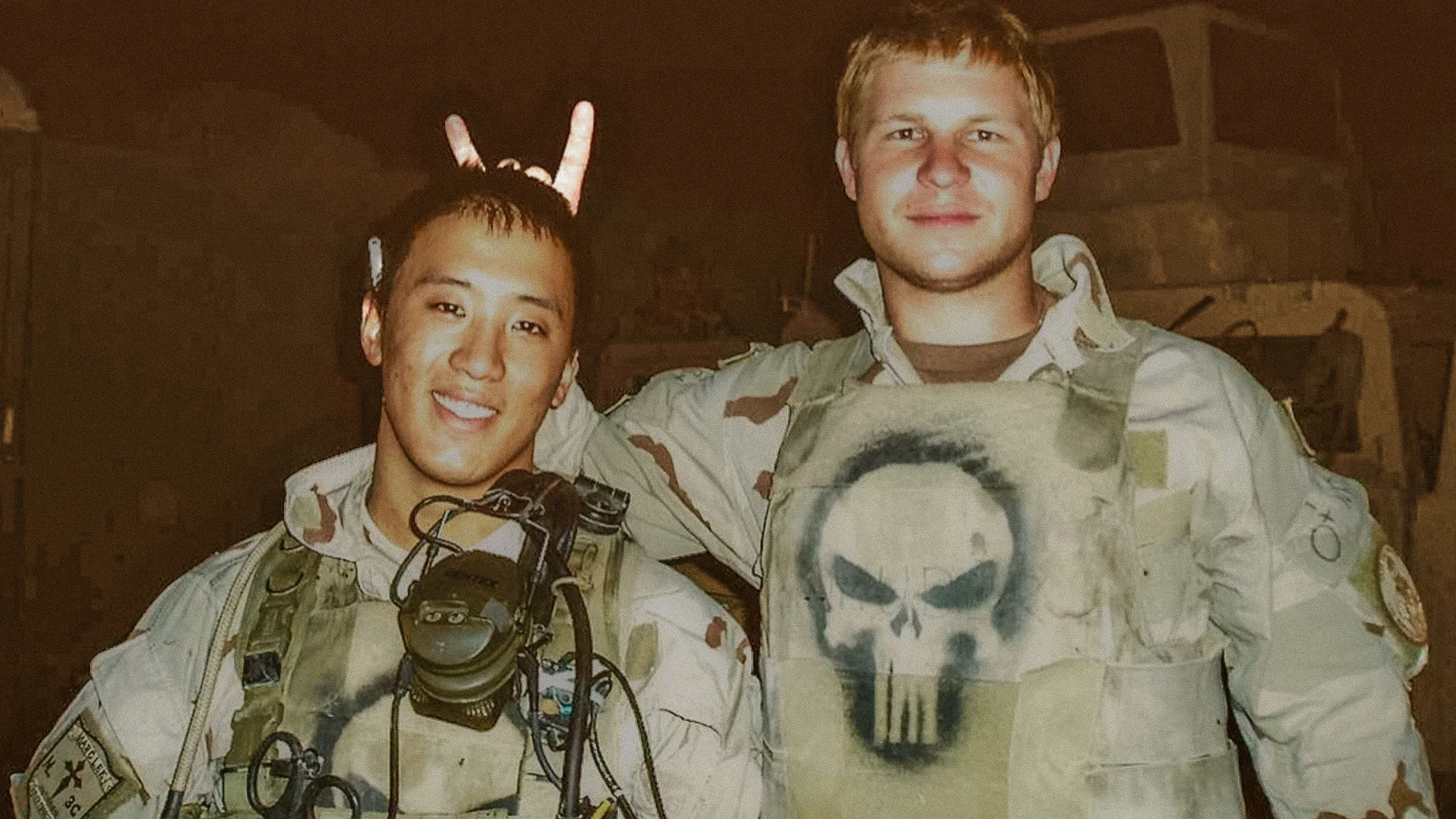

Jonny Kim was a member of legendary Task Force Bruiser during the Battle of Ramadi. Photo courtesy of Reddit.

Jonny Kim was a member of legendary Task Force Bruiser during the Battle of Ramadi. Photo courtesy of Reddit.Medical Doctor

Ultimately, despite all that he endured and accomplished as a SEAL, the experience did not transform Kim in the way he had hoped or expected. Instead of filling him with confidence, it left him angry and bitter. Yet, as far as his future was concerned, it also revealed a path forward.

The deaths of Kim’s teammates weighed heavily on his conscience — particularly the death of his close friend, Ryan Jobe, who was shot in the face during a mission in Ramadi. Kim believes that Jobe may have survived had it not been for a procedure performed by an Army physician that only exacerbated his injuries.

Kim also blamed himself, telling Willink he felt guilty for not doing more to protect his friend. The whole ordeal eventually led him to the realization that being an elite trigger-puller wasn’t his true calling. What he really wanted to do was help others.

“It took years for me to learn to be human again, to let go of that anger, to sublimate all those experiences and all those raw emotions into good,” Kim said on the Jocko Podcast. “I owed it to them to be a positive mark on this world. That’s why I wanted to be a physician.”

Kim left the SEALs in 2009 to pursue a career in emergency medicine. He became a full-time student and graduated from the University of San Diego in 2012. He then attended Harvard Medical School, earning his M.D. in 2016.

Kim conducted his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. It was there, while working in the emergency room, that he met and befriended another physician, Scott Parazynski, who would convince Kim to set his professional aspirations even higher — to space.

Astronaut and Aviator

At Parazynski’s urging, Kim eventually applied to NASA. In 2017, he was one of 12 astronaut candidates selected from a pool of more than 18,300 applicants. Once selected, Kim completed three years of training in robotics, geology, and Russian. In January 2020, he officially became the third former Navy SEAL to become a NASA astronaut.

After joining NASA’s Astronaut Group 22, Kim underwent flight training at Naval Air Station Whiting Field. He graduated in March 2023 with the rare dual-designation of both a Naval aviator and a flight surgeon. Currently, he and 17 other astronauts are training for a moon-landing mission scheduled to take place in 2024.

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.