Some great Sailors who fought for the wrong side! Grumpy

Category: Hard Nosed Folks Both Good & Bad

Two of the best dogs I ever had were Princess & Smedley. All the cats for block around diappeared. Yes I really do hate Cats.

Grumpy

Field Marshal Rommel was a formidable foe. Here’s what America learned from him.

Editor’s Note: For today’s #ThrowbackThursday, we’re examining the lessons the Allied powers learned in World War II from one of America’s most formidable enemies at the time.

Arguably the greatest general that Germany produced during WWII was Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), The Desert Fox. A career soldier, he fought during both World Wars, and became so revered for his tactical leadership skills and aggressive battlefield style that some Allied forces began to believe he was superhuman. To that point, the British Army Commander-in-Chief C.J. Auchinleck, issued the following order to his officers:

There exists a real danger that our friend Rommel is becoming a kind of magician or bogey-man to our troops, who are talking far too much about him. He is by no means a superman, although he is undoubtedly very energetic and able.

Even if he were a superman, it would still be highly undesirable that our men should credit him with supernatural powers. I wish you to dispel by all possible means the idea that Rommel represents something more than an ordinary German general.

The important thing now is to see that we do not always talk of Rommel when we mean the enemy in Libya. We must refer to “the Germans” or “the Axis powers” or “the enemy” and not always keep harping on Rommel. Please ensure that this order is put into immediate effect, and impress up all commanders that, from a psychological point of view, it is a matter of highest importance.

No, Rommel was not superhuman, but he did have what the Germans called (big-word warning) Fingerspitzengefuhl, an innate sixth sense of what the enemy was about to do. For instance, a German general, Fritz Bayerlein, Rommel’s Chief-of-Staff at the time, relates the following two anecdotes.

“We were at the headquarters of the Afrika Korps…when suddenly Rommel turned to me and said, ‘Bayerlein, I would advise you to get out of this [location]: I don’t like it.’ An hour later the headquarters were unexpectedly attacked and overrun.”

Bayerlein continues, “That same afternoon, we were standing together when he [Rommel] said, ‘Let’s move a couple of hundred yards to a flank, I think we are going to get shelled here.’ One bit of desert was just the same as another, but five minutes after we had moved, the shells were falling exactly where we had been standing. Everyone…who fought with Rommel in either war will tell you similar stories.”

Rommel also had the ability to quickly size up a battle in progress, and the decision-making skills to then seize the opportunity to attack when one presented itself. Consequently, he earned a reputation for, at times, making rash decisions, but those decisions seemed to pay off for him and his armies more times than not.

A trait that endeared Rommel to his vanguard troops was that he “led from the front,” spending nearly as much time with the frontline, everyday soldier as he did with his officers back at headquarters. As a result, his soldiers were willing to follow him anywhere.

Another characteristic that helped make Rommel the military legend he became was that he was constantly learning, not only from his victories, but also his defeats—especially his defeats, which seemed to haunt him. And he was open to new ideas, new equipment, new weapons, anything that would make his armies more efficient and in turn, more successful.

For example, Rommel did not invent blitzkrieg—a highly mobile style of warfare employing armored, motorized forces—but he and his 7th Panzer Division of tanks certainly perfected it in France during 1940. Later in the war, his Afrika Korps then continued using the technique in the deserts of North Africa to win battle after battle.

Rommel had always been a prolific writer, and following his time in Africa he authored a paper titled The Rules of Desert Warfare, the small portions below being just a few of the more interesting excerpts from the six-page document.

- The tank force is the backbone of the motorized army. Everything turns on the tanks, the other formations are mere ancillaries. War of attrition against the enemy tank units must, therefore, be carried on as far as possible by one’s own tank destruction units…[they] must deal the last blow.

- Results of reconnaissance must reach the commander in the shortest possible time, and he must then make immediate decisions and put them into effect as quickly as possible. Speed of reaction in Command decisions decides the battle. It is, therefore, essential that commanders of motorized forces should be as near as possible to their troops and in the closest signal communication with them.

- It is my experience that bold decisions give the best promise of success. One must differentiate between operational and tactical boldness and a military gamble. A bold operation is one which has no more than a chance of success but which, in case of failure, leaves one with sufficient forces in hand to be able to cope with any situation. A gamble, on the other hand, is an operation which can lead either to victory or to the destruction of one’s own forces. Any compromise is bad.

- One of the first lessons which I drew from my experiences of motorized warfare was that speed of operation and quick reaction of the Command were the decisive factors. The troops must be able to operate at the highest speed and in complete coordination. One must not be satisfied here with any normal average but must always endeavor to obtain the maximum performance, for the side which makes the greater effort is the faster, and the faster wins the battle. Officers and NCOs must, therefore, constantly train their troops with this in view.

- In my opinion, the duties of the Commander-in-Chief are not limited to his staff work. He must also take an interest in the details of Command and frequently busy himself in the front line.

- The Commander-in-Chief must have contact with his troops. He must be able to feel and think with them. The soldier must have confidence in him. In this connection there is one cardinal principle to remember: one must never simulate a feeling for the troops which in fact one does not have. The ordinary soldier has a surprisingly good nose for what is genuine and what is fake.

In the WWII movie Patton, released in 1970, actor George C. Scott portrays the brash and flamboyant American General George S. Patton. Near the end of the movie, after Patton and his army have defeated Rommel and his troops, Patton shouts loudly across the battlefield in victory, “Rommel, you magnificent b______, I read your book!”

The book he was referring to was Rommel’s Infanterie Greift An (Infantry Attacks). Published in 1937, it chronicles his experiences during World War I. If you’d care to read it, the treatise will give you a look into the mind of one of the greatest tactical military geniuses of the 20th Century. The Rommel Papers, edited by B. H. Liddell Hart and published in 1953, is also highly recommended, relating Rommel’s WWII experiences in his own words.

In the English language, the word legacy has multiple meanings. It can be used as a noun or an adjective to describe outdated computer software, a gift by will of an heirloom or money, or something transmitted or received from an ancestor or predecessor.

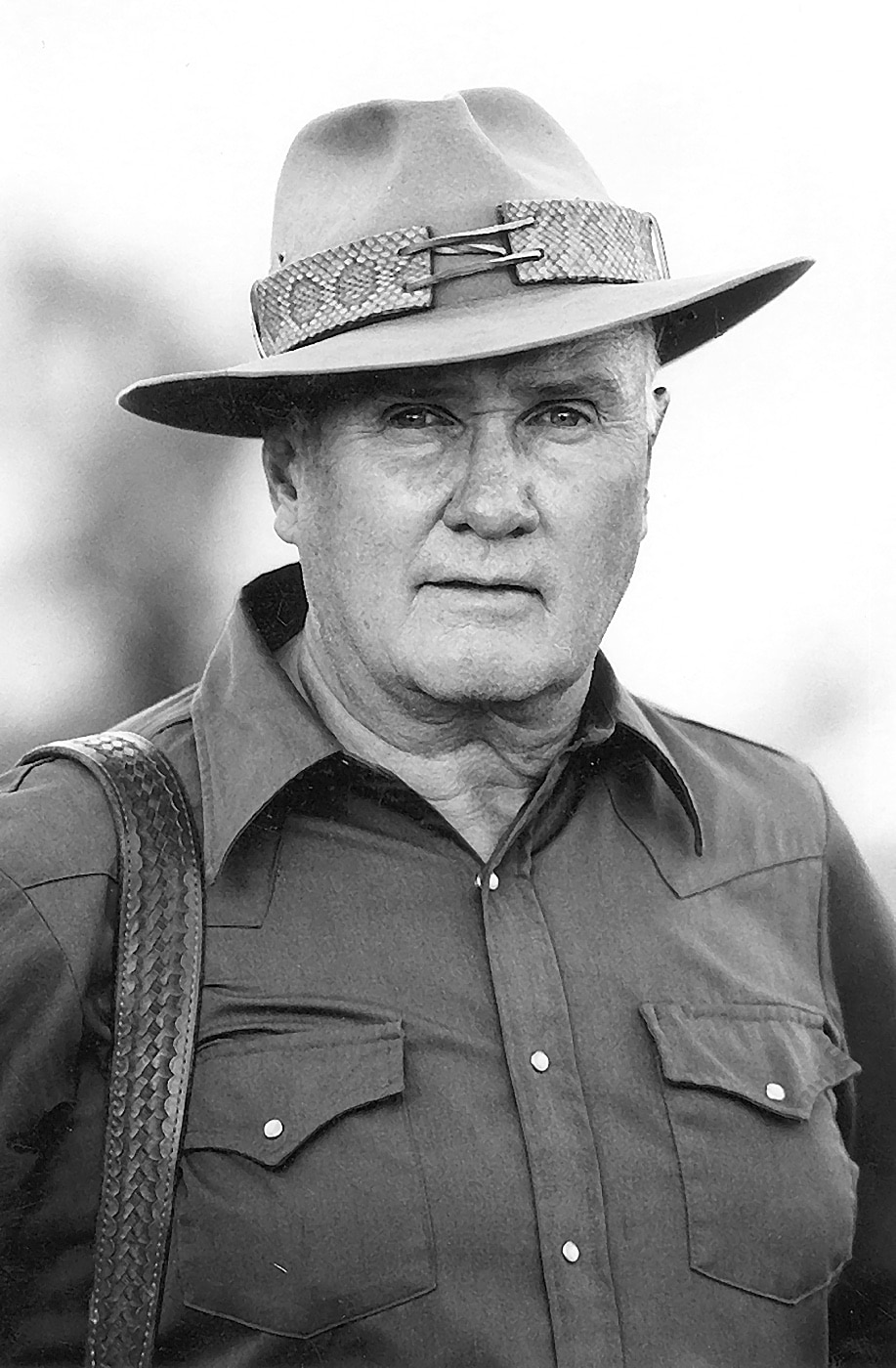

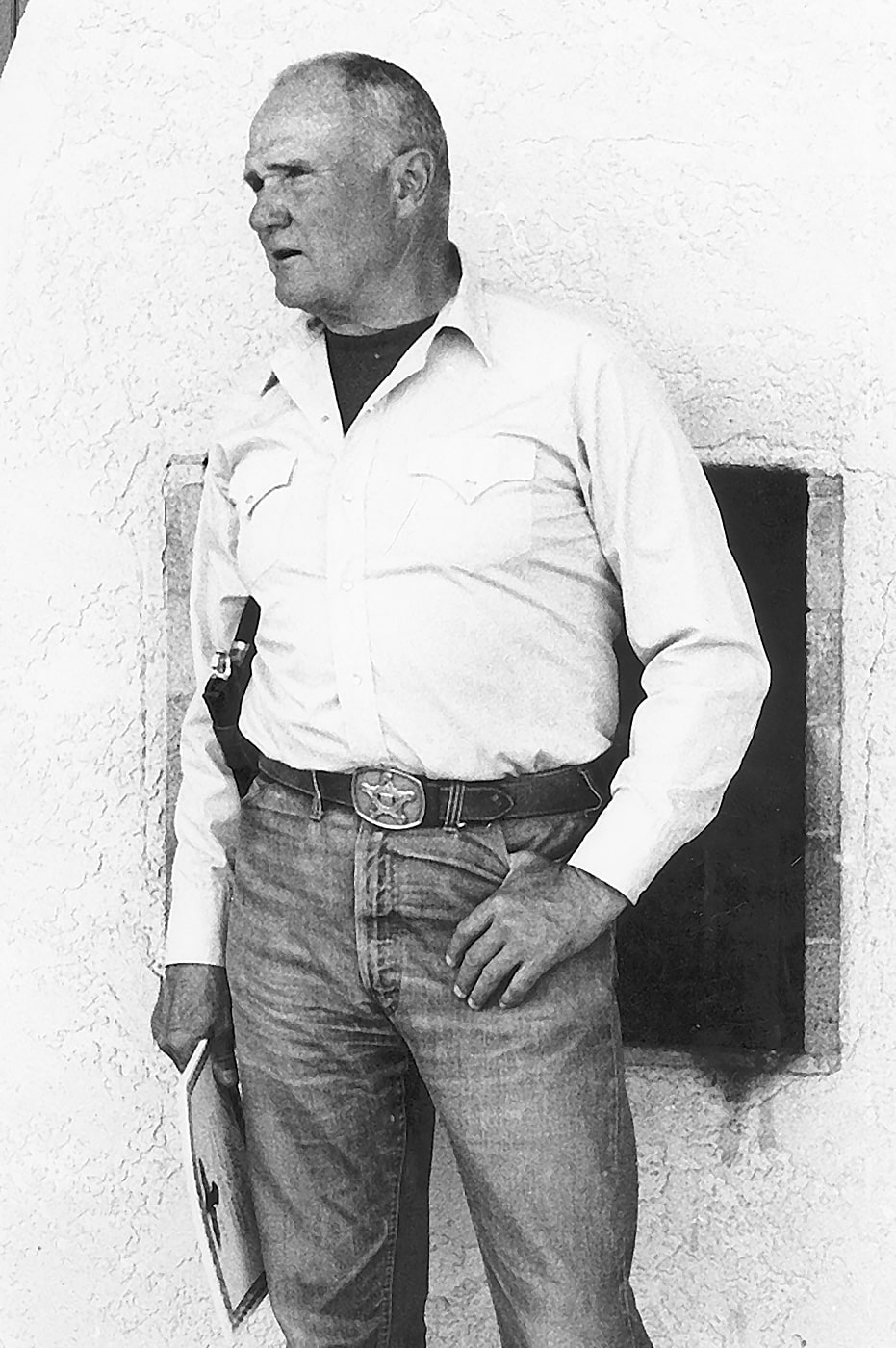

When we consider the origins of modern pistolcraft, the legacy of Jeff Cooper is without peer. The doctrine he pioneered well over a half-century ago rings true to this day and has yet to be surpassed in my opinion. In recent times, a few contemporary trainers have indeed advanced the art, but for me their contributions pale when compared to those of Lt. Col. Cooper.

Throughout his life, Jeff Cooper wore many hats with distinction. He was a Marine officer, shooter, race car driver, big game hunter, instructor and the world’s foremost expert on small arms. He was born in Los Angeles, California in 1920 and was a graduate of Los Angeles High School and Stanford University where he was enrolled in the ROTC.

Just prior to World War II, he was commissioned as an officer in the Marine Corps where he served in the Pacific Theater. After the war, he was transferred to the Marine base in Quantico, Virginia, where he became an instructor in firearms. Because of its close proximity to the FBI Academy, Colonel Cooper was able to interact with members of the Bureau and explore and develop his thoughts on handguns for personal defense.

After leaving the Marine Corps, Lt. Col. Cooper moved to Big Bear Lake in California, where he organized shooting contests called Leatherslap. With his highly analytical mind, he was able to make a determination on what techniques worked best and how they might be applied to personal defense. In many ways, this was the genesis of the Modern Technique of the Pistol.

Around the same time, Lt. Col. Cooper had established himself as a gunwriter of note and soon developed a huge following. In 1976, he established the American Pistol Institute, the first training school to offer combat pistol training to the general population. The school is now known as Gunsite and is widely recognized as one of the world’s most prestigious shooting institutions.

The Modern Technique of the Pistol

Prior to the introduction of the Modern Technique, combat pistolcraft had not evolved much since the 1930s. Large unobstructed targets were the order of the day along with generous time frames. A great deal of unsighted fire was proscribed, often at unrealistic distances. When I first entered law enforcement, this was still the prevailing doctrine and it would be quite some time before things began to change.

The Modern Technique of the Pistol is a total system that addresses mindset and gun handling as well as practical marksmanship. There is much more to winning a fight than being a good shot, and placing equal focus on mindset and gun handling was a revolutionary thought back in the day. Giving equal attention to practical marksmanship, gun handling and mindset describes the Combat Triad, part of his training and the ultimate key to success in armed conflict in my mind.

In many ways, the Modern Technique of the Pistol represented a 180-degree flip over what came before, and much of it was in conflict with what I had been previously taught. I absorbed pieces of it through Cooper’s articles, but at that time I wasn’t able to buy into it fully. However, change was in the wind.

Without question, the FBI holds great influence with other domestic law enforcement agencies relative to both training and equipment. In the early 1980s, the FBI adopted a great deal of the philosophy of the Modern Technique of the Pistol and began to teach many of the components to its agents.

I still have a VHS tape produced by the Bureau at that time and used it for years in my training. With the FBI endorsement of many of its elements, the Modern Technique quickly became very popular in law enforcement circles. As a pretty green firearms instructor at that time, I knew where I had to go to get the real message and shortly thereafter I was able to travel to Arizona and take a class at API.

For those not familiar with it, the Modern Technique is comprised of five elements. They include:

- The Weaver stance

- The flash sight picture

- The compressed surprise break

- The presentation

- The heavy-duty pistol

Even the most casual observer of combat pistolcraft associates Lt. Col. Cooper with the 1911 .45 ACP pistol, and the reason is quite simple. The single-action 1911 pistol is an easy pistol to shoot to a high standard and, back in the day, the .45 ACP cartridge was far superior to the lesser options. Today, with improvements in handgun ammunition, that point may be debated. But at one time, the .45 ACP was the undisputed king of the hill.