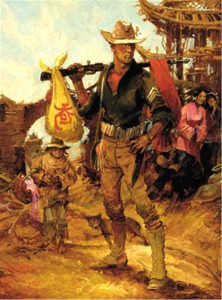

A Old China Hand during the Boxer Rebellion

USMC Non Com in China early 1900s

458 winchester magnum

A handcuffed enlistee, a burning B-17, and a stubborn ball turret gunner who just wouldn’t quit. Maynard “Snuffy” Smith was flawed, fiery, and absolutely fearless.

From Pedestals to People: Why Flawed Men Still Do Great Things

We expect way too much out of our pastors and our heroes. We put those guys on pedestals that we ourselves could never successfully occupy. To hold such folks to an unreasonable standard simply invites disappointment.

History is littered with examples. The Israelite King David killed a man and stole his wife, yet was described in scripture as a man after God’s own heart.

Martin Luther King defined the Civil Rights movement with his mantra of non-violence, and was likely the sole reason our great nation did not dissolve into anarchy. However, King was also a serial philanderer who plagiarized significant portions of his doctoral dissertation.

Charles Dickens was history’s alpha novelist, yet he was terribly abusive to his wife and children.

Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence by day and made babies with his slaves by night.

William Shockley invented the transistor and was the father of the modern computer, yet was an unrepentant racist and a strident proponent of eugenics. For all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. That’s in the Book…

I’ll let you in on a little secret: We all suck–Every. Last. One. Of. Us.

If ever I felt otherwise, those flawed assumptions were thoroughly put to rest the moment I became a physician and started trying to fix other people’s many manifest problems. Everybody on Planet Earth is just a hot mess. That includes your sweet grandmother and Mother Theresa.

As a result, have reasonable expectations as regards the people in your life. Don’t be surprised when everybody else in the world struggles with the same stuff you do. Tragically, that’s just part of being human.

Origin Story: From Courtroom to Cockpit in Wartime

Maynard Harrison Smith was born on 19 May 1911 in Caro, Michigan. His Dad was a lawyer, and his Mom taught school. From the very beginning, Maynard was a difficult kid. He sought out trouble at every opportunity. This earned him a billet at Howe Military Academy in lieu of High School.

Like most such broken souls, Maynard Smith found it impossible to stay married. He wed Arlene McCreedy, but that only lasted three years. Two years after that, his Dad died and left Maynard a little money. The young man subsequently quit his job with the US Treasury Department and lived off his inheritance. In 1941, Maynard married Helen Gunsell and fathered a son. They split up about a year later.

Maynard supposedly refused to pay child support and was subsequently dragged before a judge. With war brewing, the magistrate gave him the option of jail or the Army. When the local newspaper ran a patriotic photograph of young men being inducted into the military, Maynard Smith was in the background in handcuffs being escorted by the local sheriff.

Uniform On, Trouble Still: Into the 306th Bomb Group

A great many folks have entered military service and discovered both maturity and depth. My time in uniform played an outsized role in my own success later in life. However, sometimes that stuff just doesn’t take. Maynard Smith was a First Sergeant’s nightmare.

Smith was a short-statured man. After basic training, he volunteered for aerial gunnery school. Prior to 1947, the US Army owned what would eventually become the Air Force under the auspices of the US Army Air Corps.

Smith volunteered for the Air Corps because he knew that would mean faster promotion and more money. After gunnery school, Smith was shipped to Bedfordshire in Southern England to join the 423d Bombardment Squadron of the 306th Bomb Group.

Ball Turret Hell: Cold, Cramped, and Nowhere to Run

Things didn’t get any better once he got to his unit. Maynard soon developed a reputation for being both obnoxious and stubborn. At some point, he earned the nickname “Snuffy” Smith, no doubt a reference to the popular period cartoon strip Barney Google and Snuffy Smith. Because of his modest height, Snuffy Smith drew the duty as a ball turret gunner.

Serving as a bomber crewman was the most dangerous job in the US military during World War 2. Fully one-fifth of all US aircrew perished in the skies above Europe and the Pacific. Of all the jobs on board US heavy bombers, that of the ball turret gunner was statistically the most hazardous.

Inside the Sphere: What a B-17 Ball Turret Demanded

Duty in the ball turret was unlike anything else in the Air Corps. The ball turret was designed to defend B17 and B24 bombers from attack directly underneath the aircraft. The Sperry ball turret was roughly 3.5 feet in diameter and weighed 850 pounds. It was constructed predominantly of transparent Plexiglas and included a pair of M2 .50-caliber belt-fed machine guns. The ball turret gunner sat in the fetal position, wrapped around the two weapons. He controlled the orientation of the turret via a firing yoke.

Duty in the ball turret was, by its nature, terribly isolating. While most of the rest of the crew could interact with each other directly, the ball turret gunner was sealed inside his big plastic sphere.

Because the turret was so small, there was no room for a parachute. Entry and exit were through the back of the contraption. To egress a disabled aircraft, the ball turret gunner had to orient the thing guns-downward such that the hatch faced the interior of the aircraft, unstrap, climb out, locate and attach his parachute, and then find his way to an exit door. That’s a big ask when the plane is shot up, on fire, and plummeting earthward.

Given its direct exposure to the rarefied high-altitude slipstream, the ball turret also got incredibly cold. Gunners were equipped with electrically-heated suits, but this was 1940’s technology. Those suits not infrequently failed. It took a special sort of soldier to thrive in a ball turret in combat.

Snuffy Goes to War: St. Nazaire, the Original Flak City

Six weeks after he arrived at his unit, Snuffy Smith flew his first combat mission. The target was the Nazi U-boat pens at St. Nazaire on the Bay of Biscay in France. The Germans knew this facility to be strategically critical and defended it accordingly with a dense array of flak guns and fighters aplenty. Allied aircrews called St. Nazaire “flak city.”

Aerial navigation in the days before electronic navaids was a sketchy proposition. Somebody made a mistake, and Snuffy’s B17 approached the heavily-defended French city of Brest at around 2,000 feet. Exposed and at low altitude, the big bomber was easy meat for German fighters and anti-aircraft artillery.

When Everything Went Wrong: Fire, Fighters, and a Choice

Smith’s plane was hit hard. A fuel tank ruptured and caught fire. With the fuselage now aflame, three of the plane’s ten crewmen bailed out. Smith clawed his way out of the ball turret and turned his attention to two remaining buddies who were too badly wounded to parachute.

Smith could have jumped himself, but not without abandoning his mates. Instead, he dressed the injured men’s wounds while also manning the bomber’s waist guns against attacking German fighters.

The fire became so hot that it melted through the Fort’s aluminum skin. Smith expended all of the plane’s fire extinguishers and discarded as much flammable material and ammunition as he could through the gaping holes burned in the plane’s fuselage. With nothing left to throw on the fire, Smith dropped his trousers and urinated on it.

Ninety minutes later, Smith’s plane landed at the first available airfield on British soil. The massive bomber broke in half immediately upon touchdown. Ground crews counted 3,500 holes from German bullets and shrapnel.

The three crewmen who bailed out were never heard from again. Snuffy Smith’s selfless actions had saved the lives of the remaining six. Journalist Andy Rooney was present at the air base where Smith’s plane landed and penned a front page story about the obstinate ball gunner’s exploits. Smith was subsequently awarded the Medal of Honor.

Medal of Honor Day… and KP Anyway

Smith was on punitive KP duty the week he was awarded his nation’s highest award for valor for arriving chronically late for command meetings.

His medal was awarded by US Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Snuffy Smith flew four more combat missions after receiving his award, but was ultimately grounded due to battle fatigue. Smith was made a unit clerk but was subsequently reduced in rank to Private because he sucked so bad at it.

Private Smith went home on 2 February 1945. Despite his checkered record, his hometown threw him a rousing parade and greeted him as a hero. Smith left the military three months later.

Whenever interviewed about his time in the military, Smith had nothing but disdain for the experience. His propensity for being difficult followed him everywhere he went. Smith bounced from job to job and suffered perennial legal problems.

The Rest of the Story: A Flawed Man, A Lasting Legacy

Smith married his third wife, Mary Rayner, in 1944. He and Mary met at a USO dance in Bedford, England, and eventually had three sons and a daughter. Snuffy Smith, the deadbeat hero, eventually settled in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he died of heart failure at age 72. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

True heroes seldom look the part. Audie Murphy weighed 112 pounds when he tried and failed to enlist in both the US Marines and the Airborne, yet ended the war as the most highly decorated soldier in American history.

Maynard Smith enlisted in handcuffs and left the military under a cloud. However, he was still nonetheless a hero of the highest order—a flawed man who did some truly amazing things.

Quick Facts: B-17 Ball Turret and Mission Details

| Role | Ball turret gunner, B17 |

|---|---|

| Unit | 423d Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bomb Group |

| Ball Turret Diameter | 3.5 feet |

| Ball Turret Weight | 850 pounds |

| Armament | 2 x M2 .50-caliber machineguns |

| First Combat Target | St. Nazaire U-boat pens |

| Aircraft Damage | 3,500 holes from bullets and shrapnel |

| Lives Saved | Six crewmen |

Pros & Cons — Hard Truths of a Ball Turret Gunner’s War

- Pros: Raw, human story of courage; vivid technical detail on ball turret life; keeps all dates and numbers; powerful, relatable voice.

- Cons: Grim imagery; not a gear review; heavy subject matter for sensitive readers.