The name was always spoken with reverence, but I had no idea who he was. Then an Army Ranger I’ll call Leroy (because that’s his name) told me he couldn’t go on my T1F Taliban Pheasant Hunt in South Dakota last year because he had a chance to meet Bob Howard, who was on his deathbed in Waco. Leroy’s decision really piqued my interest. Nobody turns down the Taliban Pheasant Hunt—and, perhaps more telling, nobody goes to Waco without a really good reason. It was then that I decided I had to find out who Howard was.

A-googling I went. And it turned out that Robert Lewis Howard was a Green Beret and a TCU grad. He had appeared in two John Wayne movies, making a parachute jump in The Longest Day and playing an airborne instructor in The Green Berets—not exactly a stretch for him. Howard was the only soldier in the history of the United States to be nominated three times for the Medal of Honor, our country’s highest military decoration, which is awarded to members of the armed forces who distinguish themselves “conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States.” The men who fought with Howard all agreed that he should have received a Medal of Honor for each one of his three citations—which explains why he was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses (the second-highest honor, given in the Army). No matter. He had plenty of other gongs and ribbons. He had a Silver Star, several Bronze Stars, and eight Purple Hearts (though he was wounded 14 times). Then there was all the stuff awarded to him by the armed forces of other grateful nations.

For the life of me, I couldn’t understand why neither I nor anyone else outside of the Army had heard of this extraordinary American. I had theories. First, many of Howard’s actions in theater were still classified. We know he was in Laos and Cambodia before we knew we were in Laos and Cambodia, but we just don’t know what he was up to, apart from getting nominated for the Medal of Honor every few months or so. This was back in the days when a clandestine operation could be run without having to broadcast it on C-SPAN first.

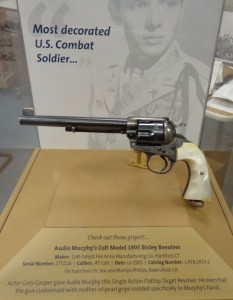

Then there was the rest of the Vietnam war, the part we knew about. Howard received his Medal of Honor from Nixon in 1971, with his sweet little first-grade daughter Missy looking on from the front row. None of the TV networks covered the event. Though Audie Murphy and Alvin York both received a Medal of Honor for their actions in World War II and the Great War respectively, and got the ticker-tape parades, fame, and fortune they both deserved, Howard got nothing, because he fought in the war that the Flower Power generation, led by Jane Fonda and her ilk, who exercised the very rights that the men and women who served in Vietnam fought to protect, demonstrated against by (among other things) spitting in the faces of returning soldiers. You can probably guess how I feel about this issue.

So after reading up on Howard, I decided to follow my friend Leroy’s lead and head down to Waco to meet the man myself. But before I could get down there, on Wednesday, December 23, 2009, Col. Robert Howard died at the age of 70. The next day, the Associated Press ran a 10-sentence obituary. The New York Times and Washington Post followed with slightly longer obits. I couldn’t believe the man’s passing had generated so little notice.

I went to Waco anyway.

Driving down I-35 toward Waco to visit Missy, the second daughter of Col. Robert Howard, I noticed for the first time that this stretch of the interstate is known as The Purple Heart Trail. I was still thinking about the coincidence when I sat down in Missy’s living room to watch a video that few people have ever seen. The video was given to Howard by the Medal of Honor Foundation.

It is Missy’s daddy at 64 years old, with a short, pale blue ribbon and small gold medal covering the knot in his tie, his jaw square and strong, his face still scarred, angular, and violently handsome. He is talking about the day he received his Medal of Honor from President Nixon, of whom he says, “He had nice hands. They were, you know, decent.”

Missy tells me that when her daddy came home to San Antonio, which wasn’t that often, he was a gardener, a gentle man with massive hands and a velvet voice who worked on his roses and never once spoke of what he did in the war. “He could make anything grow,” Missy says.

Now the Colonel’s ocean-blue eyes are focused on some far-away hellhole jungle clearing. Howard says the Hueys took ground fire on the way down to the landing zone, and his platoon suffered casualties even before it landed. But there was no peeling off for this group. Silver wings upon their chests, these are men, America’s best. (No longer do these words remind me of Bill Murray in a greenskeeper’s shed.)

“We finally got in on the ground, and I got with [the] lieutenant,” Howard says. “He says, ‘Bob, we need to secure this LZ [landing zone], and I want you to get a couple of men and secure the exterior of the LZ.’ And I got three men behind me, and I can remember being fired at. I fell backward and they killed three men behind me, and I’m firing and killing the North Vietnamese that’s trying to kill us. So I made my way back to the lieutenant and told him that the LZ was completely surrounded. By that time, one of the helicopters had been shot down.”

This is the only personal account on record of the events for which he received the Medal of Honor. To begin with, Howard seems uncomfortable talking about it. But this is not the most difficult thing he has done. He pauses and draws a breath, then begins to explain dispassionately what happened when the men resumed their operation and a grenade explosion knocked him unconscious.

“When I come to, I was blown up in a crump on the ground, and my weapon was blown out of my hand. I can remember seeing red and saying a prayer, hoping I wasn’t blind. I couldn’t see. And I knew I was in a lot of pain and my hands were hurting. I couldn’t get up, and I really didn’t want to get up anyway because I couldn’t see. And then I finally starting getting the vision back and it was like blood was in my eyes, and I started feeling, but my hands were all blown up.

“And then it was like there was a big flame and there was smoke and there were people screaming and hollering. It in fact was an enemy soldier that was burning the people that would have been ambushed with a flamethrower. And the guy walked up to me and was getting ready to burn me, and he looked at me and he didn’t burn the lieutenant. The lieutenant was about 5 feet away from me, and he’s laying face forward, and he was hollering and he was screaming. I knew he was hurt. And the guy looked at me with the flamethrower, and then I looked at him. I guess I looked so bad and pitiful, he decided not to burn me up. He just turned and walked off.”

Now Howard was unarmed, and his hands had been blown apart. He was peppered with shrapnel. He couldn’t walk. So he grabbed the lieutenant’s shirt and starting dragging him—a big man, maybe 6-foot-4 and 200 pounds—toward safety as an estimated two enemy companies fired on them.

The great man’s face changes as he talks. His jaw stiffens, and his eyes, though narrowing, seem to take on an even more penetrating blueness. I am mesmerized as he relives these moments.

“So I’m pulling him back down the hill, and there was a sergeant that was laying down behind a log with a weapon that hadn’t been wounded that had seen this. But he was crying and not using his weapon. Here I am, begging him to help me because I can’t walk and drag the lieutenant back down.

“I said, ‘Well, give me your weapon,’ and he wouldn’t give me his weapon, but he did give me a .45. Just as he gave me the .45, and I’m trying to tell him to give me a couple more magazines of rounds for it, a bunch of enemy soldiers come running toward us. So here I am trying to fire the handgun, and I can remember shooting this enemy soldier that was fixing to stick me with a bayonet. He was running toward me. In fact, he fell across the lieutenant that I was dragging, and so just as he fell across there was another one behind him. They were trying to get us alive is what they were trying to do.”

The sergeant finally began to fire his weapon, and Howard got hit again. A bullet smashed into a magazine in his ammo belt for his rifle, setting off the rounds he was carrying. Howard estimates he was hit with 15 or 20 rounds of exploding ammunition.

“Here I am thinking, I’m blowing up again,” he says. “And there were other soldiers back behind him that hadn’t been hurt at all that had been watching us being almost executed by the enemy and not doing anything, not even firing their weapons.”

Howard eventually got the lieutenant to a medic. His platoon was trapped under heavy fire and had now suffered too many casualties to fight the enemy on their terms. The medic propped Howard up, and he told his brothers, “We are going to establish a perimeter right here, and you’re going to fight or die.” Then Howard did the unthinkable. He got a radio and called in an air strike on his own position. He ordered the men to make a triangle with three strobe lights around their position to keep from getting hit.

“They brought the fire into our position,” Howard says. “In fact, I remember fire landing right between my feet and, you know, ricochet hitting me in the face. You know, that’s how intense it was.”

Eventually, helicopters were able to extract the men. Out of 37 soldiers who were ambushed that day, six survived, largely due to Howard’s heroics and quick thinking. He acted in a similarly heroic manner and endured similar injuries, saving the lives of many others on two other separate occasions for which he was nominated for the Medal of Honor.

Ten lines. That’s what the Associated Press gave Col. Robert Howard.

Back among the living in Waco, I notice that Missy has inherited her father’s looks. She is slender and beautiful. Her husband Frank Gentsch is athletic and carries his badge and handgun in the comfortable, easy manner one might expect of Waco’s chief of detectives. Frank says that before his first date with Missy, the colonel showed him how he’d kill a man with his bare hands. That must have been a little unsettling, but Frank still has a bullet in his back, so you know the old man was proud of him. On Missy’s lap sits their adopted 3-year-old daughter, Isabella, with a snubby little nose and the cutest fuzzy fro held back with a pink headband. Howard adored her—as he did his other children and grandchildren.

The life of a soldier, especially a Special Forces one, is complicated. There are top-secret stories that can’t be told and endless questions. “When is Daddy coming home?” Or worse: “Will Daddy come home?” Howard was married three times and remained close only to those who “got him.” Like so many of our fighting men and women, he felt tremendous guilt over the many times he was forced to choose between his country and his family.

After his discharge when he was 53 years old, Howard spent 13 years processing claims for the Department of Veterans Affairs and spent most of the last three years of his life in Iraq and Afghanistan, visiting troops, giving talks, and boosting morale. For a soldier, meeting Bob Howard was like a religious experience. Shaking his hand was an honor never to be forgotten. You see, they knew who he was. They got him.

We American civilians can say what we like about the morality of any war, but we should support the American soldiers and their allies whom we have sent to wage it. I’ve visited military hospitals, psych wards, and VAs in Dallas and around this country, and I’ve seen them. Mostly from Korea and Vietnam. Old, unkempt men, the military bearing and pride they once had now gone. Sometimes the only evidence it ever existed is on a battered regimental or naval ball cap. They rock back and forth, mumbling into full jungle beards, with rheumy, blast-zone-empty eyes. Or they sit in pairs, often holding hands, together and alone with horror-story memories that play over and over in their heads. Some sit with their imaginary long-dead friends, whose body parts still lie in the killing fields upon which they once so bravely fought. To America’s eternal shame, for many of them home is a sterile corner of the Cuckoo’s Nest, freezing and drunk under a highway bridge, or, if they are lucky, a spare room in the house of a worn-out son or daughter.

At least Bob Howard was spared that fate. Pancreatic cancer finally stopped him. As the disease spread to his lungs and lymph nodes, his expiry date drew closer, and he was visited by more and more soldiers, most of them old friends. But there were a few lucky youngsters, too, of whom Leroy was one of the last.

And there was always Missy, there with him every day with Isabella. Sometimes his granddaughter Holley, the starting catcher for the Texas Tech softball team, would visit. Or Tori, whom the colonel always called “Victoria.” Tori was always heartbroken when she had to leave her grandpa’s bedside and was a constant comfort to both the colonel and Missy at the end. Howard’s eldest son, Robert, is at Fort Bragg, going through Special Forces school.

As a soldier, Robert had already seen how his father acted around other military men. But for Missy and the other children, their father’s illness, and the parade of visitors it occasioned, showed them something new about their father. When Missy and the grandchildren were around, Howard was the gentle old gardener, the same man they had always known. But when a soldier entered his hospice room, he would stiffen. His voice changed to gravel, and any sign of vulnerability evaporated. He would laugh and bellow orders until the soldier was gone, and then there he’d be again: the gardener with the sparkling blue eyes, smothered in children whom he’d caress with rough, scarred hands.

By all accounts, Howard was a spectacularly bad patient. He was a nightmare for his nurses, refusing to take the painkillers, often swilling them around, then spitting them out after the nurse had left. He was going to be clearheaded until the end.

After yet another astonishing fight, during which the family was told on several occasions that Howard had only hours left, the head of the world’s most dangerous gardener finally fell sideways onto his beloved Missy’s shoulder, and America lost what was arguably her greatest warrior ever.

The name Robert Lewis Howard belongs beside George Washington, John Paul Jones, Chesty Puller, Alvin York, and Audie Murphy, to name a few of the greatest. By the time anyone reads this, Howard will have been lain to rest at Arlington the day before I became an American citizen. I would have given anything to have been with Missy, Frank, and the rest of the family on that day, but I know the colonel would have barked at me to get my worthless foreign ass to my swearing-in ceremony.

Col. Robert Howard’s funeral cortege should have started at the foot of the Jefferson Memorial. His flag-draped casket should have passed through streets lined with thousands of grateful, flag-waving Americans to Arlington, where, in preparation for his final resting place, some politician had been dug up and tossed into the Potomac. But that didn’t happen.

Ten lines. A couple of longer obits here and there. That’s all he got.

On the drive back to Dallas from Waco, I got to thinking. We should rename that stretch of I-35 after him. The Col. Robert Howard Highway. People would shorten it, of course: the Howard.

His life deserves more. But it’s a start.

David Feherty is a golf analyst for CBS Sports.