I have always found “The Good Roosevelt” to be a refreshing kind of guy. So I thought I would share some of the things that I found on the net I hope that you like this!

Ker

As you an see the Old Boy really got around.

Since he is the only American so far to have been awarded the Presidency of the United States, The Nobel Peace Prize and the Medal of Honor.

(His Son -Theodore Jr got his for his actions as a Brigadier General on D Day at Normandy. Generals do not usually get that medal at that rank by the way.)

Roosevelt’s 1903 Springfield Rifle – The later it belonged to Kermit Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt’s son

I just wish we had more like him around!

I will post some more stuff about him later on.

Thanks for your time on this!

Grumpy

Category: All About Guns

What Every Gun Lover needs!

The Howdah Gun

Now back in the Glory Days of the British Empire and the Raj. If you were very rich or had gotten in trouble at home.

The Thing to do was to escape Blighty and head out to one of the Colonies. Especially if you were greedy & or Blood thirsty. Even more especially after the Sepoy Mutiny.

So as you went East of Suez. You would of course be invited to a Tiger Hunt. If you were of the right sort of chap naturally.

Yeah right, uh moving on.

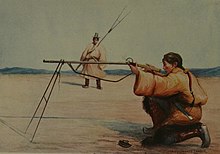

How the Howah was usually used. Now back in the day. They way one properly hunted Tigers in India was on top of an Elephant.

If a Tiger decided to come join you in your basket. Then you had your handy dandy Howdah guns to greet him with. So as you can guess by now. These guns packed quite a punch.

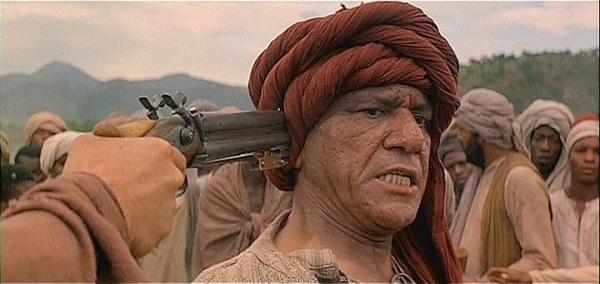

The Howdah Pistol can also be very useful in Labor Negotiations with the locals at times. (Film The Ghost & The Darkness. Great Film by the way)

Anyways here is some other videos and other information about these heavy hitters.

Howdah pistol

Double barrel .50 caliber (13mm) howdah pistol made in Germany

The howdah pistol was a large-calibre handgun, often with two or four barrels, used in India and Africa from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and into the early twentieth century, during the period of British Colonial rule. It was typically intended for defence against tigers, lions, and other dangerous animals that might be encountered in remote areas. Multi-barreled breech-loading designs were later favoured over the original muzzle-loading designs for Howdah pistols, because they offered faster reloading than was possible with contemporary revolvers,[1]which had to be loaded and unloaded through a gate in the side of the frame.

The term “howdah pistol” comes from the howdah, a large platform mounted on the back of an elephant. Hunters, especially during the period of the British Raj in India, used howdahs as a platform for hunting wild animals and needed large-calibre side-arms for protection from animal attacks.[2] The practice of hunting from the howdah basket on top of an Asian elephant was first made popular by the joint Anglo-Indian East India Company during the 1790s. These earliest howdah pistols were flintlock designs, and it was not until about 60 years later percussion models in single or double barrel configuration were seen. By the 1890s and early 1900s cartridge-firing and fully rifled howdah pistols were in normal, everyday use.

The first breech-loading howdah pistols were little more than sawn-off rifles,[2]typically in .577 Snider[3] or .577/450 Martini–Henry calibre. Later English firearms makers manufactured specially-designed howdah pistols[3] in both rifle calibres and more conventional handgun calibres such as .455 Webley and .476 Enfield.[2]As a result, the term “howdah pistol” is often applied to a number of English multi-barrelled handguns such as the Lancaster pistol (available in a variety of calibres from .380″ to .577″),[4] and various .577 calibre revolvers produced in England and Europe for a brief time in the mid-late 19th century.[5]

Even though howdah pistols were designed for emergency defense from dangerous animals in Africa and India, British officers adopted them for personal protection in other far-flung outposts of the British Empire.[3] By the late 19th century, top-break revolvers in more practical calibres (such as .455 Webley) had become widespread,[3] removing much of the traditional market for howdah pistols.

Modern reproductions are available from Italian gun maker Pedersoli in .577 and .50 calibers, as well as in 20 bore.

Lee–Enfield

| Lee–Enfield | |

|---|---|

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I (1903), Swedish Army Museum, Stockholm.

|

|

| Type | Bolt-action rifle |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | MLE: 1895–1926 SMLE: 1904–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | Second Boer War World War I Easter Rising Various Colonial conflicts Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War World War II Indonesian National Revolution Indo-Pakistani Wars Greek Civil War Malayan Emergency French Indochina War Korean War Arab-Israeli War Suez Crisis Border Campaign (Irish Republican Army) Mau Mau Uprising Vietnam War The Troubles Sino-Indian War Bangladesh Liberation War Soviet invasion of Afghanistan Nepalese Civil War Afghanistan conflict |

| Production history | |

| Designer | James Paris Lee, RSAF Enfield |

| Produced | MLE: 1895–1904 SMLE: 1904–present |

| No. built | 17,000,000+[1] |

| Variants | See Models/marks |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 4.19 kg (9.24 lb) (Mk I) 3.96 kg (8.73 lb) (Mk III) 4.11 kg (9.06 lb) (No. 4) |

| Length | MLE: 49.6 in (1,260 mm) SMLE No. 1 Mk III: 44.57 in (1,132 mm) SMLE No. 4 Mk I: 44.45 in (1,129 mm) LEC: 40.6 in (1,030 mm) SMLE No. 5 Mk I: 39.5 in (1,003 mm) |

| Barrel length | MLE: 30.2 in (767 mm) SMLE No. 1 Mk III: 25.2 in (640 mm) SMLE No. 4 Mk I: 25.2 in (640 mm) LEC: 21.2 in (540 mm) SMLE No. 5 Mk I: 18.8 in (480 mm) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | .303 Mk VII SAA Ball |

| Action | Bolt-action |

| Rate of fire | 20–30 aimed shots per minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 744 m/s (2,441 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 550 yd (503 m)[2] |

| Maximum firing range | 3,000 yd (2,743 m)[2] |

| Feed system | 10-round magazine, loaded with 5-round charger clips |

| Sights | Sliding ramp rear sights, fixed-post front sights, “dial” long-range volley; telescopic sights on sniper models. Fixed and adjustable aperture sights incorporated onto later variants. |

The Lee–Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating rifle that was the main firearm used by the military forces of the British Empireand Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century. It was the British Army‘s standard rifle from its official adoption in 1895 until 1957.[3][4]. It is often referred to as the “SMLE,” which is short for “Short Magazine Lee-Enfield”.

A redesign of the Lee–Metford (adopted by the British Army in 1888), the Lee–Enfield superseded the earlier Martini–Henry, Martini–Enfield, and Lee–Metford rifles. It featured a ten-round box magazine which was loaded with the .303 Britishcartridge manually from the top, either one round at a time or by means of five-round chargers. The Lee–Enfield was the standard issue weapon to rifle companies of the British Army and other Commonwealth nations in both the Firstand Second World Wars (these Commonwealth nations included Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and South Africa, among others).[5] Although officially replaced in the UK with the L1A1 SLR in 1957, it remained in widespread British service until the early/mid-1960s and the 7.62 mm L42 sniper variant remained in service until the 1990s. As a standard-issue infantry rifle, it is still found in service in the armed forces of some Commonwealth nations,[6] notably with the Bangladesh Police, which makes it the second longest-serving military bolt-action rifle still in official service, after the Mosin–Nagant.[7] The Canadian Rangers reserve unit still use Enfield rifles, with plans to replace the weapons sometime in 2017–2018 with the new Sako-designed Colt C-19.[8] Total production of all Lee–Enfields is estimated at over 17 million rifles.[1]

The Lee–Enfield takes its name from the designer of the rifle’s bolt system—James Paris Lee—and the factory in which it was designed—the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. In Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Southern Africa and India the rifle became known simply as the “three-oh-three“[9] or the “three-naught-three“.

Contents

[hide]

- 1Design and history

- 2Magazine Lee–Enfield

- 3Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I

- 4Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III

- 5Pattern 1914/US M1917

- 6Inter-war period

- 7Lee–Enfield No. 1 Mk V

- 8Rifle No. 4

- 9Rifle No. 5 Mk I—the “Jungle Carbine”

- 10Lee–Enfield conversions and training models

- 11Special Service Lee–Enfields: Commando and Automatic models

- 12Conversion to 7.62×51mm NATO

- 13Production and manufacturers

- 14The Lee–Enfield in military/police use today

- 15The Lee–Enfield in civilian use

- 16Users

- 17See also

- 18Notes

- 19References

- 20External links

Design and history

The Lee–Enfield rifle was derived from the earlier Lee–Metford, a mechanically similar black-powder rifle, which combined James Paris Lee‘s rear-locking bolt system with a barrel featuring rifling designed by William Ellis Metford. The Lee action cocked the striker on the closing stroke of the bolt, making the initial opening much faster and easier compared to the “cock on opening” (i.e., the firing pin cocks upon opening the bolt) of the Mauser Gewehr 98 design. The rear-mounted lugs place the bolt operating handle much closer to the operator, over the trigger, making it quicker to operate than traditional designs like the Mauser.[4] The action features helical locking surfaces (the technical term is interrupted threading). This means that final head space is not achieved until the bolt handle is turned down all the way. The British probably used helical locking lugs to allow for chambering imperfect or dirty ammunition and that the closing cam action is distributed over the entire mating faces of both bolt and receiver lugs. This is one reason the bolt closure feels smooth. The rifle was also equipped with a detachable sheet-steel, 10-round, double-column magazine, a very modern development in its day. Originally, the concept of a detachable magazine was opposed in some British Army circles, as some feared that the private soldier might be likely to lose the magazine during field campaigns. Early models of the Lee–Metford and Lee–Enfield even used a short length of chain to secure the magazine to the rifle.[10]

The fast-operating Lee bolt-action and 10-round magazine capacity enabled a well-trained rifleman to perform the “mad minute” firing 20 to 30 aimed rounds in 60 seconds, making the Lee–Enfield the fastest military bolt-action rifle of the day. The current world record for aimed bolt-action fire was set in 1914 by a musketry instructor in the British Army—Sergeant Instructor Snoxall—who placed 38 rounds into a 12-inch-wide (300 mm) target at 300 yards (270 m) in one minute.[11]Some straight-pull bolt-action rifles were thought faster, but lacked the simplicity, reliability, and generous magazine capacity of the Lee–Enfield. Several First World War accounts tell of British troops repelling German attackers who subsequently reported that they had encountered machine guns, when in fact it was simply a group of well-trained riflemen armed with SMLE Mk III rifles.[12][13]

The Lee–Enfield was adapted to fire the .303 British service cartridge, a rimmed, high-powered rifle round. Experiments with smokeless powder in the existing Lee–Metford cartridge seemed at first to be a simple upgrade, but the greater heat and pressure generated by the new smokeless powder wore away the shallow, rounded, Metford rifling after approximately 6000 rounds.[3] Replacing this with a new square-shaped rifling system designed at the Royal Small Arms Factory (RSAF) Enfield solved the problem, and the Lee–Enfield was born.[3]

Models/marks of Lee–Enfield Rifle and service periods

-

Model/Mark In Service Magazine Lee–Enfield 1895–1926 Charger Loading Lee–Enfield 1906–1926 Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I 1904–1926 Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk II 1906–1927 Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III/III* 1907–present Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk V 1922–1924 (trials only; 20,000 produced) Rifle No. 1 Mk VI 1930–1933 (trials only; 1,025 produced) Rifle No. 4 Mk I 1931–present (2,500 trials examples produced in the 1930s, then mass production from mid-1941 onwards) Rifle No. 4 Mk I* 1942–present Rifle No 5 Mk I “Jungle Carbine” 1944–present (produced 1944–1947) BSA-Shirley produced 81,329 rifles and ROF Fazakerley 169,807 rifles. Rifle No. 4 Mk 2 1949–present Rifle 7.62mm 2A 1964–present Rifle 7.62mm 2A1 1965–present

Magazine Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield rifle was introduced in November 1895 as the .303 calibre, Rifle, Magazine, Lee–Enfield,[3] or more commonly Magazine Lee–Enfield, or MLE (sometimes spoken as “emily” instead of M, L, E). The next year, a shorter version was introduced as the Lee–Enfield Cavalry Carbine Mk I, or LEC, with a 21.2-inch (540 mm) barrel as opposed to the 30.2-inch (770 mm) one in the “long” version.[3] Both underwent a minor upgrade series in 1899 (the omission of the cleaning / clearing rod), becoming the Mk I*.[14] Many LECs (and LMCs in smaller numbers) were converted to special patterns, namely the New Zealand Carbine and the Royal Irish Constabulary Carbine, or NZ and RIC carbines, respectively.[15] Some of the MLEs (and MLMs) were converted to load from chargers, and designated Charger Loading Lee–Enfields, or CLLEs.[16]

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I

A shorter and lighter version of the original MLE—the famous Rifle, Short, Magazine, Lee–Enfield, or SMLE (sometimes spoken as “Smelly”, rather than S, M, L, E)[7]—was introduced on 1 January 1904.[17] The barrel was now halfway in length between the original long rifle and the carbine, at 25.2 inches (640 mm).[17]

The SMLE’s visual trademark was its blunt nose, with only the bayonet boss protruding a small fraction of an inch beyond the nosecap, being modeled on the Swedish Model 1894 Cavalry Carbine. The new rifle also incorporated a charger loading system,[18] another innovation borrowed from the Mauser rifle’[19] and is notably different from the fixed “bridge” that later became the standard, being a charger clip (stripper clip) guide on the face of the bolt head. The shorter length was controversial at the time: many Rifle Association members and gunsmiths were concerned that the shorter barrel would not be as accurate as the longer MLE barrels, that the recoil would be much greater, and the sighting radius would be too short.[20]

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III

The iconic Lee–Enfield rifle, the SMLE Mk III, was introduced on 26 January 1907, along with a Pattern 1907 (P’07) sword bayonet and featured a simplified rear sight arrangement and a fixed, rather than a bolt-head-mounted sliding, charger guide.[7] The design of the handguards and the magazine were also improved, and the chamber was adapted to fire the new Mk VII High Velocity spitzer .303 ammunition. Many early model rifles, of Magazine Lee–Enfield (MLE), Magazine Lee–Metford (MLM), and SMLE type, were upgraded to the Mk III standard. These are designated Mk IV Cond., with various asterisks denoting subtypes.[21]

During the First World War, the SMLE Mk III was found to be too complicated to manufacture (an SMLE Mk III rifle cost the British Government £3/15/-) and demand was outstripping supply, so in late 1915 the Mk III* was introduced, which incorporated several changes, the most prominent of which were the deletion of the magazine cut-off mechanism, which when engaged permits the feeding and extraction of single cartridges only while keeping the cartridges in the magazine in reserve, and the long-range volley sights.[19][21][22][23] The windage adjustment of the rear sight was also dispensed with, and the cocking piece was changed from a round knob to a serrated slab.[23] Rifles with some or all of these features present are found, as the changes were implemented at different times in different factories and as stocks of existing parts were used.[24] The magazine cut-off was reinstated after the First World War ended and not entirely dispensed with until 1942.[23]

The inability of the principal manufacturers (RSAF Enfield, The Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited and London Small Arms Co. Ltd) to meet military production demands, led to the development of the “peddled scheme”, which contracted out the production of whole rifles and rifle components to several shell companies.[25]

The SMLE Mk III* (renamed Rifle No.1 Mk III* in 1926) saw extensive service throughout the Second World War as well, especially in the North African, Italian, Pacific and Burmese theatres in the hands of British and Commonwealth forces. Australia and India retained and manufactured the SMLE Mk III* as their standard-issue rifle during the conflict and the rifle remained in Australian military service through the Korean War, until it was replaced by the L1A1 SLR in the late 1950s.[26] The Lithgow Small Arms Factory finally ceased production of the SMLE Mk III* in 1953.[21]

The Rifle Factory at Ishapore, West Bengal, India produced the MkIII* in .303 British and then upgraded the manufactured strength by heat treatment of the receiver and bolt to fire 7.62×51mm NATO ammunition, the model 2A, which retained the 2000 yard rear sight as the metric conversion of distance was very close to the flatter trajectory of the new ammunition nature, then changed the rear sight to 800m with a re-designation to model 2A1. Manufactured until at least the 1980s and continues to produce a sporting rifle based on the MkIII* action.

Pattern 1913 Enfield

Due to the poor performance of the .303 British cartridge during the Second Boer War from 1899–1902, the British attempted to replace the round and the Lee–Enfield rifle that fired it. The main deficiency of the rounds at the time was that they used heavy, round-nosed bullets that had low muzzle velocities and poor ballistic performance. The 7mm Mauserrounds fired from the Mauser Model 1895 rifle had a higher velocity, flatter trajectory and longer range, making them superior on the open country of the South African plains. Work on a long-range replacement cartridge began in 1910 and resulted in the .276 Enfield in 1912. A new rifle based on the Mauser design was created to fire the round, called the Pattern 1913 Enfield. Although the .276 Enfield had better ballistics, troop trials in 1913 revealed problems including excessive recoil, muzzle flash, barrel wear and overheating. Attempts were made to find a cooler-burning propellant but further trials were halted in 1914 by the onset of World War I. This proved fortunate for the Lee–Enfield, as wartime demand and the improved Mk VII loading of the .303 round, caused it to be retained for service.[27]

Pattern 1914/US M1917

The Pattern 1914 Enfield and M1917 Enfield rifles are based on the Enfield-designed P1913, itself a Mauser 98 derivative and not based on the Lee action, and are not part of the Lee–Enfield family of rifles, although they are frequently assumed to be.[28]

Inter-war period

In 1926, the British Army changed their nomenclature; the SMLE became known as the Rifle No. 1 Mk III or III*, with the original MLE and LEC becoming obsolete along with the earlier SMLE models.[29] Many Mk III and III* rifles were converted to .22 rimfire calibre training rifles, and designated Rifle No. 2, of varying marks. (The Pattern 1914 became the Rifle No. 3.)[29]

The SMLE design was a relatively expensive long arm to manufacture, because of the many forging and machiningoperations required. In the 1920s, a series of experiments resulting in design changes were carried out to help with these problems, reducing the number of complex parts and refining manufacturing processes. The SMLE Mk V (later Rifle No. 1 Mk V), adopted a new receiver-mounted aperture sighting system, which moved the rear sight from its former position on the barrel.[30] The increased gap resulted in an improved sighting radius, improving sighting accuracy and the aperture improved speed of sighting over various distances. In the stowed position, a fixed distance aperture battle sight calibrated for 300 yd (274 m) protruded saving further precious seconds when laying the sight to a target. An alternative developed during this period was to be used on the No. 4 variant, a “battle sight” was developed that allowed for two set distances of 300 yards and 600 yards to be quickly deployed and was cheaper to produce than the “ladder sight”. The magazine cutoff was also reintroduced and an additional band was added near the muzzle for additional strength during bayonet use.[30] The design was found to be even more complicated and expensive to manufacture than the Mk III and was not developed or issued, beyond a trial production of about 20,000 rifles between 1922 and 1924 at RSAF Enfield.[30] The No. 1 Mk VI also introduced a heavier “floating barrel” that was independent of the forearm, allowing the barrel to expand and contract without contacting the forearm and interfering with the ‘zero’, the correlation between the alignment of the barrel and the sights. The floating barrel increased the accuracy of the rifle by allowing it to vibrate freely and consistently, whereas wooden forends in contact with barrels, if not properly fitted, affected the harmonic vibrations of the barrel. The receiver-mounted rear sights and magazine cutoff were also present and 1,025 units were produced between 1930 and 1933.[31]

Lee–Enfield No. 1 Mk V

Long before the No. 4 Mk I, Britain had obviously settled on the rear aperture sight prior to WWI, with modifications to the SMLE being tested as early as 1911, as well as later on the No. 1 Mk III pattern rifle. These unusual rifles have something of a mysterious service history, but represent a missing link in SMLE development. The primary distinguishing feature of the No. 1 Mk V is the rear aperture sight. Like the No. 1 Mk III* it lacked a volley sight and had the wire loop in place of the sling swivel at the front of magazine well along with the simplified cocking piece. The Mk V did retain a magazine cut-off, but without a spotting hole, the piling swivel was kept attached to a forward barrel band, which was wrapped over and attached to the rear of the nose cap to reinforce the rifle for use with the standard Pattern 1907 bayonet. Other distinctive features include a nose cap screw was slotted for the width of a coin for easy removal, a safety lever on the left side of the receiver was slightly modified with a unique angular groove pattern, and the two-piece hand guard being extended from the nose cap to the receiver, omitting the barrel mounted leaf sight. No. 1 Mk V rifles were manufactured solely by R.S.A.F. Enfield from 1922–1924, with a total production of roughly 20,000 rifles, all of which marked with a “V”.

Rifle No. 4

By the late 1930s, the need for new rifles grew and the Rifle, No. 4 Mk I was officially adopted in 1941.[32] The No. 4 action was similar to the Mk VI, but stronger and most importantly, easier to mass-produce.[33] Unlike the SMLE, that had a nose cap, the No 4 Lee–Enfield barrel protruded from the end of the forestock. The charger bridge was no longer rounded for easier machining. The iron sightline was redesigned and featured a rear receiver aperture battle sight calibrated for 300 yd (274 m) with an additional ladder aperture sight that could be flipped up and was calibrated for 200–1,300 yd (183–1,189 m) in 100 yd (91 m) increments. This sight line like other aperture sight lines proved to be faster and more accurate than the typical mid-barrel rear sight elements sight lines offered by Mauser, previous Lee–Enfields or the Buffington battle sight of the 1903 Springfield.

The No. 4 rifle was heavier than the No. 1 Mk. III, largely due to its heavier barrel and a new bayonet was designed to go with the rifle: a spike bayonet, which was essentially a steel rod with a sharp point and was nicknamed “pigsticker” by soldiers.[33] Towards the end of the Second World War, a bladed bayonet was developed, originally intended for use with the Sten gun—but sharing the same mount as the No. 4’s spike bayonet—and subsequently the No. 7 and No. 9 blade bayonets were issued for use with the No. 4 rifle as well.[34]However, in McAuslan in the Rough, George MacDonald Fraser alleges that the Pattern 1907 bladed bayonet used with the SMLE was also compatible with the No. 4 rifle.[35]

During the course of the Second World War, the No. 4 rifle was further simplified for mass-production with the creation of the No. 4 Mk I* in 1942, with the bolt release catch replaced by a simpler notch on the bolt track of the rifle’s receiver.[36] It was produced only in North America, by Long Branch Arsenal in Canada and Savage-Stevens Firearms in the USA.[36]The No.4 Mk I rifle was primarily produced for the United Kingdom.[37]

In the years after the Second World War, the British produced the No. 4 Mk 2 (

…

[Message clipped] View entire message

The M-1 Garand

But even then you are doing some pretty good shooting there partner!

M1 Garand

| U.S. rifle, caliber .30, M1 | |

|---|---|

M1 Garand rifle. From the collections of the Swedish Army Museum, Stockholm, Sweden.

|

|

| Type | Semi-automatic rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1936–1959 (as the standard U.S. service rifle)1940s–present (other countries) |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars |

|

| Production history | |

| Designer | John C. Garand |

| Designed | 1928 |

| Manufacturer |

|

| Unit cost | About $85 (during World War II) ($1,200 in 2016 dollars) |

| Produced | 1934—1956 |

| No. built | 5,468,772[3] |

| Variants | M1C, M1D |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 9.5 lb (4.31 kg) to 11.6 lb (5.3 kg) |

| Length | 43.5 in (1,100 mm) |

| Barrel length | 24 in (609.6 mm) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge |

|

| Action | Gas-operated, rotating bolt |

| Rate of fire | 40−50 rounds/min |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,800 ft/s (853 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 500 yd (457 m)[4] |

| Feed system | 8-round en-bloc clip, internal magazine |

| Sights |

|

The M1 Garand[nb 1] is a .30 calibersemi-automatic rifle that was the standard U.S. service rifle during World War II and the Korean Warand also saw limited service during the Vietnam War. Most M1 rifles were issued to U.S. forces, though many hundreds of thousands were also provided as foreign aid to American allies. The Garand is still used by drill teams and military honor guards. It is also widely used by civilians for hunting, target shooting, and as a military collectible.

The M1 rifle was named after its Canadian-Americandesigner, John Garand. It was the first standard-issue semi-automatic military rifle.[5]By all accounts the M1 rifle served with distinction. General George S. Patton called it “the greatest battle implement ever devised”.[6][7]The M1 replaced the bolt action M1903 Springfield as the standard U.S. service rifle in the mid 1930s, and was itself replaced by the selective fireM14 rifle in the early 1960s.

Although the name “Garand” is frequently pronounced /ɡəˈrænd/, the preferred pronunciation is /ˈɡærənd/ (to rhyme with errand), according to experts and people who knew John Garand, the weapon’s designer.[8][9] Frequently referred to as the “Garand” or “M1 Garand” by civilians, its official designation when it was the issue rifle in the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps was “U.S. Rifle, Caliber 30, M1” or just “M1” and Garand was not mentioned.

Contents

[hide]

History

Development

French Canadian-born Garand went to work at the United States Army’s Springfield Armory and began working on a .30 caliber primer actuated blowbackModel 1919 prototype. In 1924, twenty-four rifles, identified as “M1922s”, were built at Springfield. At Fort Benningduring 1925, they were tested against models by Berthier, Hatcher-Bang, Thompson, and Pedersen, the latter two being delayed blowback types.[10] This led to a further trial of an improved “M1924” Garand against the Thompson, ultimately producing an inconclusive report.[10] As a result, the Ordnance Board ordered a .30-06 Garand variant. In March 1927, the cavalry board reported trials among the Thompson, Garand, and 03 Springfield had not led to a clear winner. This led to a gas-operated .276 (7 mm) model (patented by Garand on 12 April 1930).[10]

In early 1928, both the infantry and cavalryboards ran trials with the .276 Pedersen T1 rifle, calling it “highly promising”[10] (despite its use of waxedammunition,[11] shared by the Thompson).[12] On 13 August 1928, a semiautomatic rifle board (SRB) carried out joint Army, Navy, and Marine Corpstrials between the .30 Thompson, both cavalry and infantry versions of the T1 Pedersen, “M1924” Garand, and .256 Bang, and on 21 September, the board reported no clear winner. The .30 Garand, however, was dropped in favor of the .276.[13]

Further tests by the SRB in July 1929, which included rifle designs by Browning, Colt–Browning, Garand, Holek, Pedersen, Rheinmetall, Thompson, and an incomplete one by White,[nb 2] led to a recommendation that work on the (dropped) .30 gas-operated Garand be resumed, and a T1E1 was ordered 14 November 1929.

Twenty gas-operated .276 T3E2 Garands were made and competed with T1 Pedersen rifles in early 1931. The .276 Garand was the clear winner of these trials. The .30 caliber Garand was also tested, in the form of a single T1E1, but was withdrawn with a cracked bolt on 9 October 1931. A 4 January 1932 meeting recommended adoption of the .276 caliber and production of approximately 125 T3E2s. Meanwhile, Garand redesigned his bolt and his improved T1E2 rifle was retested. The day after the successful conclusion of this test, Army Chief of StaffGeneral Douglas MacArthur personally disapproved any caliber change, in part because there were extensive existing stocks of .30 M1 ball ammunition.[14] On 25 February 1932, Adjutant General John B. Shuman, speaking for the secretary of war, ordered work on the rifles and ammunition in .276 caliber cease immediately and completely and all resources be directed toward identification and correction of deficiencies in the Garand .30 caliber.[12]:111

On 3 August 1933, the T1E2 became the “semi-automatic rifle, caliber 30, M1”.[10] In May 1934, 75 M1s went to field trials; 50 were to infantry, 25 to cavalry units.[12]:113 Numerous problems were reported, forcing the rifle to be modified, yet again, before it could be recommended for service and cleared for procurement on 7 November 1935, then standardized 9 January 1936.[10] The first production model was successfully proof-fired, function-fired, and fired for accuracy on July 21, 1937.[15]

Production difficulties delayed deliveries to the army until September 1937. Machine production began at Springfield Armory that month at a rate of ten rifles per day,[16] and reached an output of 100 per day within two years. Despite going into production status, design issues were not at an end. The barrel, gas cylinder, and front sight assembly were redesigned and entered production in early 1940. Existing “gas-trap” rifles were recalled and retrofitted, mirroring problems with the earlier M1903 Springfield rifle that also had to be recalled and reworked approximately three years into production and foreshadowing rework of the M16 rifle at a similar point in its development. Production of the Garand increased in 1940 despite these difficulties,[17] reaching 600 a day by 10 January 1941,[10] and the army was fully equipped by the end of 1941.[14] Following the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Winchester was awarded an “educational” production contract for 65,000 rifles,[10] with deliveries beginning in 1943.[10]

Service use

The M1 Garand was made in large numbers during World War II, approximately 5.4 million were made.[18]They were used by every branch of the United States military. By all accounts the M1 rifle served with distinction. General George S. Patton called it “the greatest implement of battle ever devised.”[7] The impact of faster-firing infantry small arms in general soon stimulated both Allied and Axis forces to greatly increase their issue of semi- and fully automaticfirearms then in production, as well as to develop new types of infantry firearms.[19]

Much of the M1 inventory in the post-World War II period underwent arsenal repair or rebuilding. While U.S. forces were still engaged in the Korean War, the Department of Defense determined a need for additional production of the Garand. Springfield Armory ramped up production but two new contracts were awarded. During 1953–56, M1s were produced by International Harvesterand Harrington & Richardson in which International Harvester alone produced a total of 337,623 M1 Garands.[20][21] A final, very small lot of M1s was produced by Springfield Armory in early 1957, using finished components already on hand. Beretta also produced Garands using Winchester tooling.

The British Army looked at the M1 as a possible replacement for its bolt-action Lee–Enfield No.1 Mk III, but it was rejected when rigorous testing suggested that it was an unreliable weapon in muddy conditions.[22][23] However, surplus M1 rifles were provided as foreign aid to American allies; including South Korea, West Germany, Italy, Japan, Denmark, Greece, Turkey, Iran, South Vietnam, etc. Most Garands shipped to allied nations were predominantly manufactured by International Harvester Corporation during the period of 1953-56, and second from Springfield Armory from all periods.[24]

Some Garands were still being used by the United States into the Vietnam War in 1963; despite the M14’s official adoption in 1957, it was not until 1965 the changeover from the M1 Garand was completed in the active-duty component of the army (with the exception of the sniper variants, which were introduced in World War II and saw action in Korea and Vietnam). The Garand remained in service with the Army Reserve, Army National Guard and the Navy, well into the 1970s or longer.

Due to widespread United States military assistance as well their durability, M1 Garands have also been turning up in modern conflicts such as with the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan.[25]

Some military drill teams still use the M1 rifle, including the U.S. Marine Corps Silent Drill Team, the United States Air Force Academy Cadet Honor Guard, the U.S. Air Force Auxiliary, almost all Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) and some Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) teams of all branches of the U.S. military.

Design details

Features

The M1 rifle is a .30 caliber, gas-operated, 8 shot clip-fed, semi-automatic rifle.[26] It is 43.6 inches (1,107 mm) long and it weighs about 9.5 pounds (4.31 kg).[27]

The M1’s safety catch is located at the front of the trigger guard. It is engaged when it is pressed rearward into the trigger guard, and disengaged when it is pushed forward and is protruding outside of the trigger guard.[28]

The M1 Garand was designed for simple assembly and disassembly to facilitate field maintenance. It can be field stripped (broken down) without tools in just a few seconds.[29]

The rifle had an iron sight line consisting of rear receiver aperture sight protected by sturdy “ears” calibrated for 100–1,200 yd (91–1,097 m) in 100 yd (91 m) increments. The bullet drop compensation was set by turning the range knob to the appropriate range setting. The bullet drop compensation/range knob can be fine adjusted by setting the rear sight elevation pinion. The elevation pinion can be fine adjusted in approximately 1 MOA increments. The aperture sight was also able to correct for wind drift operated by turning a windage knob that moved the sight in approximately 1 MOA increments. The windage lines on the receiver to indicate the windage setting were 4 MOA apart. The front sighting element consisted of a wing guards protected front post.

During World War II the M1 rifle’s semiautomatic operation gave United States infantrymen a significant advantage in firepower and shot-to-shot recovery time over enemy infantrymen armed primarily with bolt-action rifles. The semi-automatic operation and reduced recoil allowed soldiers to fire 8 rounds as quickly as they could pull the trigger, without having to move their hands on the rifle and therefore disrupt their firing position and point of aim.[30] The Garand’s fire rate, in the hands of a trained soldier, averaged 40–50 accurate shots per minute at a range of 300 yards (270 m). “At ranges over 500 yards (460 m), a battlefield target is hard for the average rifleman to hit. Therefore, 500 yards (460 m) is considered the maximum effective range, even though the rifle is accurate at much greater ranges.”[27]

En bloc clip

The M1 rifle is fed by an “en bloc” clip which holds eight rounds of .30-06 Springfield ammunition. When the last cartridge is fired, the rifle ejects the clip and locks the bolt open.[31] The M1 is now ready to reload. Once the clip is inserted, the bolt snaps forward on its own as soon as thumb pressure is released from the top round of the clip, chambering a round and leaving it ready to fire.[32][33]Although it is not absolutely necessary, the preferred method is to place the back of the right hand against the operating rod handle and press the clip home with the right thumb; this releases the bolt, but the hand restrains the bolt from slamming closed on the operator’s thumb (resulting in “M1 thumb”); the hand is then quickly withdrawn, the operating rod moves forward and the bolt closes with sufficient force to go fully to battery. Thus, after the clip has been pressed into position in the magazine, the operating rod handle should be released, allowing the bolt to snap forward under pressure from the operating rod spring. The operating rod handle may be smacked with the palm to ensure the bolt is closed.[28][33]

Contrary to widespread misconception, partially expended or full clips can be easily ejected from the rifle by means of the clip latch button.[28] It is also possible to load single cartridges into a partially loaded clip while the clip is still in the magazine, but this requires both hands and a bit of practice. In reality, this procedure was rarely performed in combat, as the danger of loading dirt along with the cartridges increased the chances of malfunction. Instead, it was much easier and quicker to simply manually eject the clip, and insert a fresh one,[34]which is how the rifle was originally designed to be operated.[33][35][36] Later, special clips holding two or five rounds became available on the civilian market, as well as a single-loading device which stays in the rifle when the bolt locks back.

In battle, the manual of arms called for the rifle to be fired until empty, and then recharged quickly. Due to the well-developed logistical system of the U.S. military at the time, this wastage of ammunition was generally not critical, though this could change in the case of units that came under intense fire or were flanked or surrounded by enemy forces.[35] The Garand’s en-bloc clip system proved particularly cumbersome when using the rifle to launch grenades, requiring removal of an often partially loaded clip of ball ammunition and replacement with a full clip of blank cartridges.

By modern standards, the M1’s feeding system is archaic, relying on clips to feed ammunition, and is the principal source of criticism of the rifle. Officials in Army Ordnance circles demanded a fixed, non-protruding magazine for the new service rifle. At the time, it was believed that a detachable magazine on a general-issue service rifle would be easily lost by U.S. soldiers (a criticism made of British soldiers and the Lee–Enfield 50 years previously), would render the weapon too susceptible to clogging from dirt and debris (a belief that proved unfounded with the adoption of the M1 Carbine), and that a protruding magazine would complicate existing manual-of-arms drills. As a result, inventor John Garand developed an “en bloc” clip system that allowed ammunition to be inserted from above, clip included, into the fixed magazine. While this design provided the requisite flush-mount magazine, the clip system increased the rifle’s weight and complexity, and made only single loading ammunition possible without a clip.

Ejection of an empty clip created a distinctive metallic “pinging” sound.[37] In World War II, reports arose in which German and Japanese infantry were making use of this noise in combat to alert them to an empty M1 rifle in order to ‘get the drop’ on their American enemies. The information was taken seriously enough that U.S. Army’s Aberdeen Proving Groundbegan experiments with clips made of various plastics in order to soften the sound, though no improved clips were ever adopted.[36] According to former German soldiers, the sound was inaudible during engagements and not particularly useful when heard, as other squad members might have been nearby ready to fire.[38] Seasoned U.S. infantry soldiers would sometimes purposely toss an empty en-bloc clip creating the same sound a Garand makes when it has fired its last shot and is empty, in an effort to draw out the enemy, with varying degrees of success.[39]

Gas system

Garand’s original design for the M1 used a complicated gas system involving a special muzzle extension gas trap, later dropped in favor of a simpler drilled gas port. Because most of the older rifles were retrofitted, pre-1939 gas-trap M1s are very rare today and are prized collector’s items.[26] In both systems, expanding gases from a fired cartridge are diverted into the gas cylinder. Here, the gases meet a long-stroke piston attached to the operating rod, which is pushed rearward by the force of this high-pressure gas. Then, the operating rod engages a rotating bolt inside the receiver. The bolt is attached to the receiver via two locking lugs, which rotate, unlock, and initiate the ejection of the spent cartridge and the reloading cycle when the rifle is discharged. The operating rod (and subsequently the bolt) then returns to its original position.

The M1 Garand was one of the first self-loading rifles to use stainless steel for its gas tube, in an effort to prevent corrosion. As the stainless metal could not be parkerized, the gas tubes were given a stove-blackening that frequently wore off in use. Unless the gas tube could be quickly repainted, the resultant gleaming muzzle could make the M1 Garand and its user more visible to the enemy in combat.[35]

Accessories

Several accessories were used with the Garand rifle. Several different styles of bayonets fit the rifle: the M1905 and M1942, both with 16-inch (406 mm) blades; the Model 1905E1 with shortened 10-inch (254 mm) blade; the M1 with 10-inch (254 mm) blade; and the

…

[Message clipped] View entire message

I do not have a dog in this fight!

BECAUSE

Since I have shot both of them a few times. From which I had a bad experience with both.

But if you folks out there are Happy with what you got. Then all I can say is this!

But if you want. Here is a pretty good video on the subject!

ME, I going shooting with my Sig Saur at the range!

Grumpy

This pistol is the one that was used to Kill the Archduke Ferdinand of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire & his wife in 1914.

This event in turn became the source of the First World War. Or as I call it, Europe’s first serious attempt at Suicide.

This what the Old boy looked like before he got shot. All by accounts he was a pretty decent guy.

This is what the punk / terrorist / freedom Fighter that pulled the Trigger looked like. He died in a Austrian prison from disease during the war.

So indirectly this nondescript looking semi automatic pistol. Is the root cause of the death of about 16 million. Also the First World War led in turn to WWII and the death of another 60 million. Give or take.

This was stolen via A Herd of The Turtles.com

Literally a Blast from the past!

I sure would not want to get hit by one of these soft lead musket balls!

Back back in the really / terrible old days of say the 1450’s to say the 1570’s Europe or Japan. Folks did not have the kind of firearms that we do not have today.

But this does not mean that they were stupid or anything even close to it. Now having discovered Gunpowder and what it can do. Thanks to the Chinese!

The ruling Class quickly began to invest on how to use it in their arguments with each other and the peasantry*. (*For most folks today that would of been us)

So the bright boys of the realm began to collectively to put their brains on this problem.

Here is what they came up with!

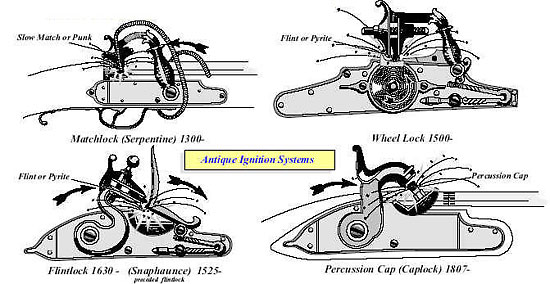

The Matchlock Musket

Okay here is what it is. Surprisingly enough. The have the basic form of today’s rifles. With a Lock to ignite the powder. The Stock to hold it up and aim with. Then the barrel to place the ammunition and help guide it toward its target.

As you no doubt have guess it already. This is a muzzle loading weapon and is a very slow and inaccurate weapon. But it was miles ahead of anything else out there at the time.

The major problems were the poor quality of gunpowder available, that you have a slow burning sulphur soaked cord near a lot of gunpowder. That and poorly bored barrels that cut down the musketeers accuracy.

Also the weather can really mess with the match. That and you could literally see the enemy coming from all the smoke.

So here is a video about how to load this puppy. Sorry its in French. But you will get the general idea about how slow reloading is.

Also if you really want to get a good taste of this era. You might also want to get the DVD of the 3 & 4 Musketeers that was made in 1974. Here is a little peek enjoy!

You also might like this one too.

Here is some more & probably better written information about the Matchlock

The matchlock was the first mechanism, or “lock”, invented to facilitate the firing of a hand-held firearm. Before this, firearms (like the hand cannon) had to be fired by applying a lit match (or equivalent) to the priming powder in the flash pan by hand; this had to be done carefully, taking most of the soldier’s concentration at the moment of firing, or in some cases required a second soldier to fire the weapon while the first held the weapon steady. Adding a matchlock made the firing action simple and reliable by a single soldier, allowing him to keep both hands steadying the gun and eyes on the target while firing.

Contents

[hide]

Description[edit]

Engraving of musketeers from the Thirty Years’ War

The classic European matchlock gun held a burning slow match in a clamp at the end of a small curved lever known as the serpentine. Upon the pulling of a lever (or in later models a trigger) protruding from the bottom of the gun and connected to the serpentine, the clamp dropped down, lowering the smoldering match into the flash pan and igniting the priming powder. The flash from the primer travelled through the touch hole igniting the main charge of propellant in the gun barrel. On release of the lever or trigger, the spring-loaded serpentine would move in reverse to clear the pan. For obvious safety reasons the match would be removed before reloading of the gun. Both ends of the match were usually kept alight in case one end should be accidentally extinguished.

Earlier types had only an “S”-shaped serpentine pinned to the stock either behind or in front of the flash pan (the so-called “serpentine lock”), one end of which was manipulated to bring the match into the pan.[1][2]

Most matchlock mechanisms mounted the serpentine forward of the flash pan. The serpentine dipped backward, toward the firer, to ignite the priming. This is the reverse of the familiar forward-dipping hammer of the flintlock and later firearms.

A later addition to the gun was the rifled barrel. This made the gun much more accurate at longer distances but did have drawbacks, the main one being that it took much longer to reload because the bullet had to be pounded down into the barrel.[3]

A type of matchlock was developed called the snap matchlock,[4] in which the serpentine was held in firing position by a weak spring,[5] and released by pressing a button, pulling a trigger, or even pulling a short string passing into the mechanism. As the match was often extinguished after its relatively violent collision with the flash pan, this type fell out of favour with soldiers, but was often used in fine target weapons.

Various Japanese (samurai) Edo period matchlocks (tanegashima).

An inherent weakness of the matchlock was the necessity of keeping the match constantly lit. The match was steeped in potassium nitrate to keep the match lit for extended periods of time.[3] Being the sole source of ignition for the powder, if the match was not lit when the gun needed to be fired, the mechanism was useless, and the weapon became little more than an expensive club. This was chiefly a problem in wet weather, when damp match cord was difficult to light and to keep burning. Another drawback was the burning match itself. At night, the match would glow in the darkness, possibly revealing the carrier’s position. The distinctive smell of burning match-cord was also a giveaway of a musketeer’s position (this was used as a plot device by Akira Kurosawa in his movie Seven Samurai). It was also quite dangerous when soldiers were carelessly handling large quantities of gunpowder (for example, while refilling their powder horns) with lit matches present. This was one reason why soldiers in charge of transporting and guarding ammunition were amongst the first to be issued self-igniting guns like the wheellock and snaphance.

The matchlock was also uneconomical to keep ready for long periods of time. To maintain a single sentry on night guard duty with a matchlock, keeping both ends of his match lit, required a mile of match per year.[6]

History[edit]

Japanese foot soldiers (ashigaru) firing tanegashima (matchlocks)

The Janissary corps of the Ottoman army were using matchlock arms from the 1440s onwards.[7] Improved versions of the arquebus were transported to India by Babur in 1526.[8][9]

The matchlock appeared in Europe in the mid-15th century (the matchlock was obsolete around 1700 in Europe),[10] with the idea of a serpentine appearing in an Austrian manuscript. The first dated illustration of a matchlock mechanism dates to 1475 (making it the first firearm with a trigger[11]) and by the 16th century they were universally used. During this time the latest tactic in using the matchlock was to line up and send off a volley of musket balls at the enemy. This volley would be much more effective than single soldiers trying to hit individual targets.[3]

China is credited with inventing both gunpowder and firearms but the matchlock was claimed to have been introduced to China by the Portuguese. Europeans refined the hand cannons that had arrived in Europe in the early 15th century and added the matchlock mechanism. The Chinese obtained the matchlock arquebus technology from the Portuguese in the 16th century and matchlock firearms were used by the Chinese into the 19th century.[12] The Chinese used the term “bird-gun” to refer to muskets and Turkish muskets may have reached China before Portuguese ones.[13]

In Japan the first documented introduction of the matchlock which became known as the tanegashima was through the Portuguese in 1543.[14] The tanegashimaseems to have been based on snap matchlocks that were produced in the armory of Goa in Portuguese India, which was captured by the Portuguese in 1510.[15]While the Japanese were technically able to produce tempered steel (e.g. sword blades), they preferred to use work-hardened brass springs in their matchlocks. The name tanegashima came from the island where a Chinese junk with Portuguese adventurers on board was driven to anchor by a storm. The lord of the Japanese island Tanegashima Tokitaka (1528–1579) purchased two matchlock rifles from the Portuguese and put a sword smith to work copying the matchlock barrel and firing mechanism. Within a few years the use of the tanegashima in battle forever changed the way war was fought in Japan.[16]

Despite the appearance of more advanced ignition systems such as that of the wheellock and the snaphance, the low cost of production, simplicity, and high availability of the matchlock kept it in use in European armies until about 1720. It was eventually completely replaced by the flintlock as the foot soldier’s main armament.

There is evidence that matchlock rifles may have been in usage among some peoples in Christian Abyssinia in the late Middle Ages. Although modern rifles were imported into Ethiopia during the 19th century, contemporary British historians noted that along with slingshots the elderly used matchlock rifle weapons for self-defense and by the militaries of the Ras.[17][18]

Modern use[edit]

| This section does not cite any sources. (June 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In Taiwan under Qing rule the Hakka on Taiwan owned matchlock muskets. Han people traded and sold matchlock muskets to the Taiwanese aborigines. During the Sino-French War the Hakka and Aboriginals used their matchlock muskets against the French in the Keelung Campaign and Battle of Tamsui.

The Hakka used their matchlock muskets to resist the Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1895) and Han Taiwanese and Aboriginals conducted an insurgency against Japanese rule.

Tibetan nomad fighters used arquebuses for warfare during the Chinese invasion of Tibet as late as the second half of the 20th century. Tibetan nomads still use matchlock rifles to hunt wolves and other predatory animals. These matchlock arquebuses typically feature a long, sharpened retractable forked stand and are part of Tibetan traditional Nomad regalia. Some of these arquebuses are engraved with silver and gold inlays and/or have damascened barrels. Early 20th century explorer Sven Hedin also encountered Tibetan tribesmen on horseback armed with matchlock rifles along the Tibetan border with Xinjiang.

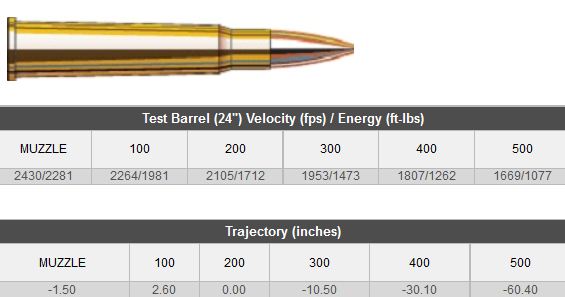

Your standard Remington 700 in 22-250. Its a great rifle after you make sure that the trigger group is squared away.

Or if you really want to go “Whole Hog” then. You do a whole lot worst than with a High Wall in the caliber.

So way back when I was in University, which was a hell of a long time ago. I started to hear and read about this round. That & a few like minded classmates of mine. Told me about what they had experienced with it.

| .22-250 Remington | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rifle | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of origin | USA | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designer | Grosvenor Wotkyns, J.E Gebby & J. Bushnell Smith | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designed | 1937 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Remington | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Produced | 1965-Present | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Variants | .22-250 Ackley Improved | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent case | .250-3000 Savage | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case type | Rimless, bottleneck | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bullet diameter | .224 in (5.7 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neck diameter | .254 in (6.5 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shoulder diameter | .414 in (10.5 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Base diameter | .469 in (11.9 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rim diameter | .473 in (12.0 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Case length | 1.912 in (48.6 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overall length | 2.35 in (60 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rifling twist | 1-12, 1-14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primer type | Large rifle | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source(s): Hodgdon [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The .22-250 Remington is a very high-velocity (capable of reaching over 4000 feet per second), short action, .22 caliber rifle cartridgepri

Contents

[hide]

History[edit]

The .22-250 started life as a wildcat cartridge developed from the .250 Savage case necked down to take a .224 caliber bullet. In the early days of the cartridge there were several different versions that varied only slightly from one to the next, including one developed in 1937 by Grosvenor Wotkyns, J.E. Gebby and J.B. Smith who named their version the 22 Varminter.[3]

The .22-250 is similar to, but was outperformed by the larger .220 Swift cartridge. However, it is in much wider use and has a larger variety of commercially available factory ammunition than the Swift. This makes it generally cheaper to shoot. The smaller powder load also contributes to more economical shooting if a person is doing their own reloads. Despite common myths regarding longer barrel life on a 22-250 vs the Swift or other calibers, that is directly related to shooter habits, allowing the barrel to cool between volleys and the speed of the bullet, an important factor for high-volume shooters. Both the Swift and the 22-250 shoot at very similar velocities and bullet weights so barrel wear when used and cooled equally is identical between the two calibers. Due to its rimless case the 22-250 also feeds from a box magazine with ease.

In 1937 Phil Sharpe, one of the first gunsmiths to build a rifle for the .22-250 and long time .220 Swift rifle builder, stated, “The Swift performed best when it was loaded to approximately full velocity,” whereas, “The Varminter case permits the most flexible loading ever recorded with a single cartridge. It will handle all velocities from 1,500ft/s up to 4,500ft/s.”[6]

Sharpe credited the steep 28-degree shoulder for this performance. He insisted that it kept the powder burning in the case rather than in the throat of the rifle, as well as prevented case stretching and neck thickening. “Shoulder angle ranks along with primer, powders, bullets, neck length, body taper, loading density and all those other features,” he wrote. “The .22 Varminter seems to have a perfectly balanced combination of all desirable features and is not just an old cartridge pepped up with new powders.”[6]

Accuracy was consistently excellent, with little need for either case trimming or neck reaming, and Sharpe pronounced it “my choice for the outstanding cartridge development of the past decade.” He finished by saying he looked forward to the day when it would become a commercial cartridge.[6]

Commercial acceptance[edit]

In 1963 the Browning Arms Company started to chamber its Browning High Power Rifle in the .22-250, at the time a wildcat cartridge. This was a risky yet historical move on Browning’s part as there was no commercial production of the .22-250 at the time. John T. Amber, reporting on the development of the Browning rifle in the 1964 Gun Digest, called the event “unprecedented”. “As far as I know,” he wrote, “this is the first time a first-line arms-maker has offered a rifle chambered for a cartridge that it—or some other production ammunition maker—cannot supply.” Amber foresaw difficulties for the company but “applauded Browning’s courage in taking this step”. He said he had his order in for one of the first heavy-barrel models, expected in June 1963, and added, “I can hardly wait!”[6]

Two years later in 1965 Remington Arms adopted the .22-250, added “Remington” to the name and chambered their Model 700 and 40 XB match rifles for the cartridge along with a line of commercial ammunition, thus establishing its commercial specification.[7]

The .22-250 was the first non-Weatherby caliber offered in the unique Weatherby Mark V rifle.

Military acceptance[edit]

Both the British Special Air Service and the Australian Special Air Service Regiment used Tikka M55 sniper rifles chambered in .22-250 for urban counter-terrorism duties in the 1980s, in an attempt to reduce excessive penetration and ricochets.[8]

Performance[edit]

Typical factory-loaded .22-250 Remington can propel a 55 grain (3.56 g) spitzer bullet at 3,680 ft/s (1122 m/s) with 1,654 ft·lbf (2,243 J) of energy.[9] Many other loads with lighter bullets are used to achieve velocities of over 4,000 ft/s (1,219 m/s), while still having effective energy for use in hunting small game and medium-sized predators.

The .22-250 is currently the fastest production cartridge, surpassing the .204 Ruger. This round is loaded by Hornady under their Superformance line and is a 35 grain, non-toxic, fragmenting varmint bullet at 4450 feet per second (1356 m/s) from a 24″ barrel.

It is particularly popular in the western states of the USA where high winds often hinder the effectiveness of other varmintrounds in prairie dog hunting. Many states in the USA have minimum caliber restrictions on larger game such as deer, although most states do allow the cartridge to be used for big game.

Israel & Guns