Categories

CZ 600 American

Categories

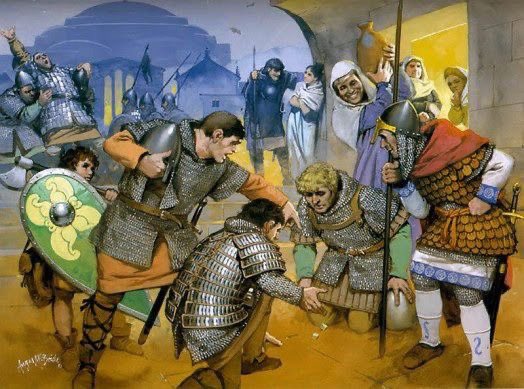

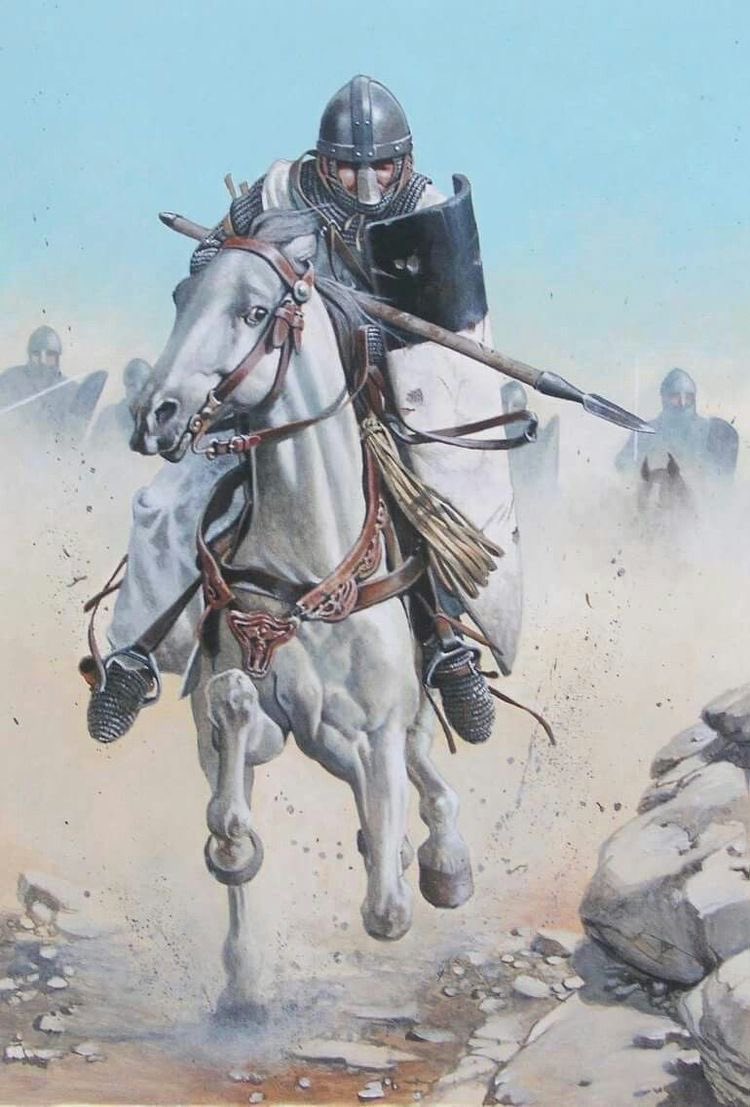

Some more art of some great Warriors

Categories

Mauser Counterbore follow-up

Categories

Shooting my Vintage Marlin 39A

Categories