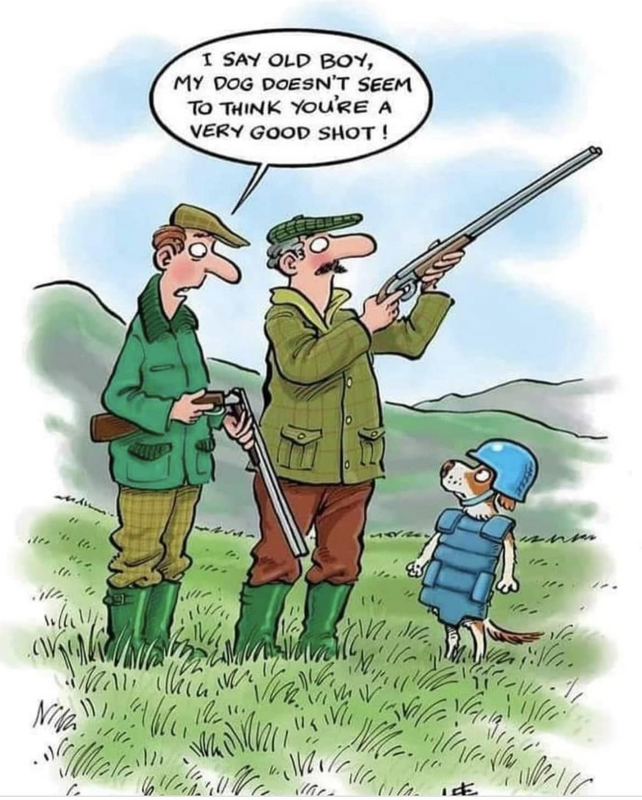

Category: Some Red Hot Gospel there!

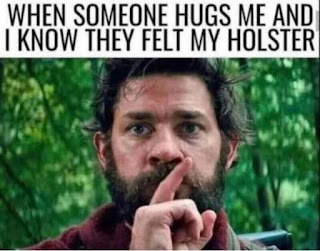

Or a Republican’s too!!! Grumpy

Categories

Well I liked them!

Categories

Some sound advice

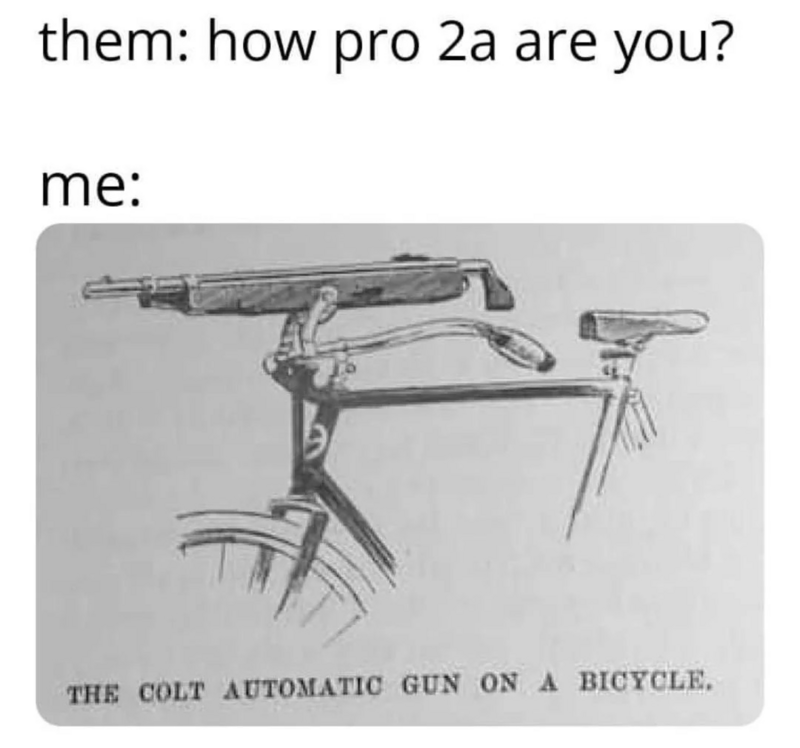

That Sir is some serious RED HOT GOSPEL!!!

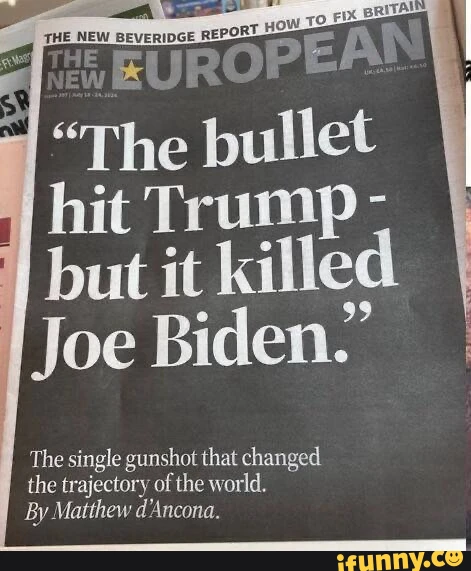

Heads need to roll on this!! The incompetence of

the Secret Service & The Local Cops is beyond

belief !!! I mean really !?! An unsecured building

that is in range & line of sight?

No Drones as a perimeter guard come on!!!

If I had been in charge of this while in the Army. I would be facing a GENERAL COURT MARTIAL & a free trip to Leavenworth !!! With Fedex sending me Daylight.

I am so pissed!

.WEBP)