Disclosure: Some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning at no additional cost to you, Ammoland will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

If you ever had a school teacher that swore that you would use and even appreciate math one day, then that promise is finally about to come true while picking a long-range caliber.

USA –-(Ammoland.com)- So, you want to shoot long-range. Excellent! I can offer a 100% money-back guarantee that you’re going to have lots of fun while learning all sorts of cool stuff.

If you ever had a school teacher that swore that you would use and even appreciate math one day, then that promise is finally about to come true. Yes, you’ll need to embrace a bit of math to master the long-range game, but it’s practical and even borders on enjoyable.

Yes, I know. I used “math” and “enjoyable” in the same sentence. On purpose. Just trust me, OK? The first time you press the trigger to nail a distance target, you’ll get a big kick out of hearing that “clang” several seconds later.

Step one is figuring out which caliber is best for you. Notice that I didn’t say “best” but rather “best for you.” There are a lot of great long-range cartridges available, and it’s pointless to try to figure out which is “best” because the answer is always… it depends. The correct question is this: Which ones are good for your intended use?

Here are a few factors to ponder before making your caliber decision

How long is the “long” in Long-Range Caliber?

Depending on where you live and plan to shoot, “long-range” might be anywhere from 200 to 2,000 yards.

Contrary to widespread assumption, bullet drop doesn’t matter all that much because it’s very predictable. That’s because gravity is reliable. Today, tomorrow, and until the world ends from some future Supreme Court pick, gravity will work exactly the same. Whether your bullet drops eight or 18 feet doesn’t matter all that much. With a good rifle, scope, and ammo, you can still make a precise hit every time, regardless of the amount of bullet drop. What does matter is the point down range at which your projectile transitions from supersonic to subsonic speeds. Up to that point on the velocity curve, bullet flight is amazingly predictable. During the subsonic transition and after, the math gets much harder and the results less precise.

The safe bet for caliber selection is to determine your realistic shooting distances and choose a caliber that remains supersonic past the distance of your longest anticipated shots.

Here’s a quick example. While 77-grain .223 Remington bullets are far better for longer range shooting than 55-grain ones, they only remain supersonic for about 750 yards here where I live. Your mileage may vary depending on your altitude and weather conditions. On the other hand, the new .224 Valkyrie, which uses the same bullet diameter, will remain supersonic past 1,000 yards here and out to 1,300 or so yards at higher altitudes.

Where will you be shooting?

When shooting at 50 or 100 yards, elevation and local atmospheric conditions don’t make a whole lot of difference.

When shooting at 1,000 yards, your location means everything. To illustrate the point, let’s consider an example using the 6.5mm Creedmoor cartridge.

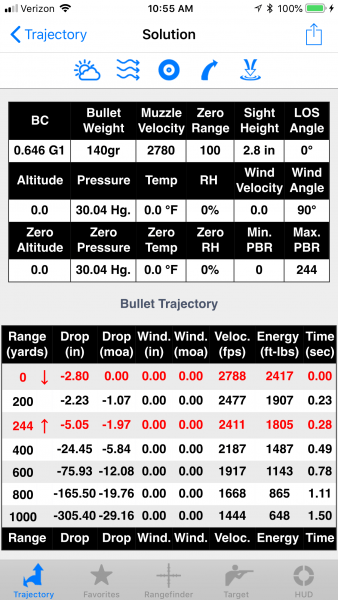

One load I’ve been using flings a Hornady 140-grain ELD Match bullet at 2,780.3 feet per second.

Where I shoot, elevation is about 30 feet above sea level. At 1,000 yards, this bullet will have dropped 305.39 inches and still be moving at 1,444 feet per second. If I were to travel to Denver with the same rifle and ammo, the bullet drop at 1,000 yards would be significantly less – 244.25 inches.

Also, the velocity would be much faster with the bullet sailing at 1,882 feet per second as it passes the 1,000-yard mark.

Are you hunting or target shooting?

As you can see from the previous example, velocity can vary – a lot – depending on where you will be shooting. In a hunting scenario, it’s up to you to make sure that you’re using a bullet of sufficient weight and velocity, not at the muzzle, but at the anticipated distance down range where it will strike the target. While the Hornady ELD Match in the previous example isn’t a hunting projectile, we can still use it as an example. In South Carolina, it’s carrying 648 foot-pounds of energy at 1,000 yards. In Denver, that bullet delivers 1,100 foot-pounds on the same 1,000-yard target. Don’t get hung up on the illustrations here as realistic hunting distances, we’re just illustrating the point that energy varies not only with distance, but location. It’s up to you to make sure you keep your shots ethical and within your capabilities.

As for target shooting, as long as your bullets don’t miss the safety berm, the energy delivered down range doesn’t matter so much. It doesn’t take much kinetic energy or momentum to perforate paper or ding a steel target. For these uses, you’ll be more concerned with factors like wind drift.

Are you going to buy or reload your long-range caliber ammo?

Depending on the caliber you choose, your costs can vary widely, at least for factory-loaded ammunition. If you decided that you just have to shoot .338 Lapua Magnum, plan on spending five to seven bucks per round for quality pre-loaded ammo. Unless your day job title is Shady Hedge Fund Manager, that can put a severe dent in your wallet. On the other hand, reloading specialty rounds like this can save you a ton if you’re willing to invest some time in the process. We’ll get into details on that in a later article in the long-range shooting series.

If you’re not ready to take a bite from the long-range caliber reloading foot-long sub, no worries. You can find great long-range calibers with excellent factory loads that are available for reasonable prices. For example, the hot new .224 Valkyrie cartridge lists for $.50 to $1.25 per round. Even the larger 6.5mm Creedmoor round comes in around $1.25 a shot for match-grade ammo.

Semi-auto or bolt-action?

If you have strong desires on the type of rifle action, that will help narrow the universe of possible calibers too. In the semi-automatic area, most long-range rifles are members of either the AR-15 or AR-10 family. Those two lower receiver types tend to limit the numbers of choices because the magazine wells are only so big, so if you plan to fire more than one shot, cartridges will need to fit in either the AR-15 or AR-10 lower receivers. In the bolt action world, things are more flexible.

Ballistic Coefficient

Here comes the dreaded math, but we’re going to keep it simple. We’re going to drill into Ballistic Coefficient in a different article, so for now, think of it this way. This numerical value assigned to every unique bullet defines how “slippery” it is while flying through the air. Stated differently, it corresponds to a bullet’s ability to retain velocity as it flies. If you could fire a Yeti cooler (with the door open) that would have a very low ballistic coefficient number. Of course, it would have the added benefit of bringing joy to Second Amendment advocates everywhere when it self-destructed on impact. On the other hand, an oversized sewing needle launched from a high-tech magnetic rail gun would have a very high ballistic coefficient.

To get practical, the new .224 Valkyrie 90-grain Sierra Matchking bullet has a ballistic coefficient of 0.563. A .308 caliber flat nose, 150-grain bullet for a .30-30 lever-action has a ballistic coefficient of just 0.185. So, yes, the ballistic coefficient number is (almost) always between zero and one, although the Yeti probably carries a BC of negative 113.9.

So, long-range caliber bullets with higher ballistic coefficients tend to carry their velocity better and as a result, act more predictably at longer ranges. That may or may not be relevant to your scenario. For example, if your goal is to knock over steel silhouette targets at 500 yards, you might be better off using a big, heavy, and fat bullet that doesn’t top the coefficient charts. Like the other factors mentioned here, the ballistic coefficient is one of many things to consider depending on what you want to do.

So, these are a few things to consider when choosing your long-range caliber. Most importantly, think about your typical use case and work backward from that.

About Tom McHale

Tom McHale is the author of the Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.