Now I am willing to bet that a (hopefully) large part of the folks who Read this rantin /Blog of mine. Have never heard of this guy.

Which is a real pity. Since he is the only Non Commissioned Officer (Sergeant) that came the closest to give General “Old Blood & Guts” george Patton a stroke*. No kidding!

So here is his story. Mauldin came from a dirt Poor farming family. From the South West part of The Great Depression America. Who discovered that he was good at drawing things. So his family sent him to an Art School in Chicago.

Then he joined the Army National Guard and specifically the hard Fighting 45th Infantry Division. He then served in the brutal Italian Campaign of WWII.

During this time. He became part at first of the 45th Division’s Newspaper. He then moved up the feeding chain of journalism.

After the end of the war, He then came home and really made a name for himself as a cartoonist. Up until his tragic death took him.

So here is some of his work. To me they really ring true. As I firmly believe that the US Army in many ways NEVER CHANGES!

He won the Pulitzer Prize for this cartoon

- *He drew the Cartoons of Willie & Joe, Who were the classic example of what a WWII Infantry Soldier looked like. They never fit what Patton thought a good soldier should look like.

- Eisenhower had to literally tell Patton to leave him alone. Since he wa so good for the Infantry’s morale.

This is his story written by himself. I think that it is one of the best books about him and the US Army in WWII from the Enlisted Side.

here is some more on his life.

Bill Mauldin

| Bill Mauldin | |

|---|---|

Bill Mauldin in 1945

|

|

| Born | William Henry Mauldin October 29, 1921 Mountain Park, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Died | January 22, 2003 (aged 81) Newport Beach, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Cartoonist, Infantryman, Actor |

| Spouse(s) | (Norma) Jean Humphries; Natalie Sarah Evans; Christine Lund |

| Children | Bruce, Tim (with Humphries); Andy, David, John, Nathaniel (with Evans); Kaja, Sam (with Lund) |

| Parent(s) | Sidney Albert Mauldin & Katrina Bemis Mauldin Curtis |

William Henry “Bill” Mauldin (/ˈmɔːldən/; October 29, 1921 – January 22, 2003) was an American editorial cartoonist who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was most famous for his World War II cartoons depicting American soldiers, as represented by the archetypal characters Willie and Joe, two weary and bedraggled infantry troopers who stoically endure the difficulties and dangers of duty in the field. His cartoons were popular with soldiers throughout Europe, and with civilians in the United States as well.

Contents

[hide]

Childhood and youth[edit]

Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, New Mexico into a family with a tradition of military service. His father served as an artilleryman in World War I, and his paternal grandfather had been a civilian cavalry scout in the Apache Wars. After growing up there and in Phoenix, Arizona, Mauldin took courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts under the tutoring of Ruth VanSickle Ford. While in Chicago, Mauldin met Will Lang Jr. and became fast friends with him. Lang Jr. later became a journalist and a bureau head for Life magazine. Mauldin entered the US Army in 1940 via the Arizona National Guard.

World War II cartoonist[edit]

While in the 45th Infantry Division, Mauldin volunteered to work for the unit’s newspaper, drawing cartoons about regular soldiers or “dogfaces“. Eventually he created two cartoon infantrymen, Willie and Joe, who represented the average American GI.

During July 1943, Mauldin’s cartoon work continued when, as a sergeant of the 45th Division’s press corps, he landed with the division in the invasion of Sicily and later in the Italian campaign.[1] Mauldin began working for Stars and Stripes, the American soldiers’ newspaper; as well as the 45th Division News, until he was officially transferred to the Stars and Stripes in February 1944.[1] Egbert White, editor of the Stars and Stripes, encouraged Mauldin to syndicate his cartoons and helped him find an agent. [2]By March 1944, he was given his own jeep, in which he roamed the front, collecting material. He published six cartoons a week.[3] His cartoons were viewed by soldiers throughout Europe during World War II, and were also published in the United States. The War Office supported their syndication,[4] not only because they helped publicize the ground forces but also to show the grim side of war, which helped show that victory would not be easy.[5] While in Europe, Mauldin befriended a fellow soldier-cartoonist, Gregor Duncan, and was assigned to escort him for a time. (Duncan was killed at Anzio in May 1944.)[6]

Mauldin was not without his detractors. His images—which often parodied the Army’s spit-shine and obedience-to-orders-without-question policy—offended some officers. After a Mauldin cartoon ridiculed General George Patton‘s decree that all soldiers be clean-shaven at all times, even in combat, Patton called Mauldin an “unpatriotic anarchist” and threatened to “throw [his] ass in jail” and ban Stars and Stripes from his Third Army jurisdiction. General Dwight Eisenhower, Patton’s superior, told Patton to leave Mauldin alone; he felt the cartoons gave the soldiers an outlet for their frustrations. “Stars and Stripes is the soldiers’ paper,” he told him, “and we won’t interfere.”[7]

In a 1989 interview, Mauldin said, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes.[8]

Mauldin’s cartoons made him a hero to the common soldier. GIs often credited him with helping them to get through the rigors of the war. His credibility with the common soldier increased in September 1943, when he was wounded in the shoulder by a German mortar while visiting a machine gun crew near Monte Cassino.[1] By the end of the war he received the Army’s Legion of Merit for his cartoons. Mauldin wanted Willie and Joe to be killed on the last day of combat, but Stars and Stripes dissuaded him.[3]

Postwar activities[edit]

In 1945, at the age of 23, Mauldin won a Pulitzer Prize for his wartime body of work, exemplified by a cartoon depicting exhausted infantrymen slogging through the rain, its caption mocking a typical late-war headline: “Fresh, spirited American troops, flushed with victory, are bringing in thousands of hungry, ragged, battle-weary prisoners”.[9] The first civilian compilation of his work, Up Front, a collection of his cartoons interwoven with his observations of war, topped the best-seller list in 1945. After war’s end, the character of Willie was featured on the cover of Time Magazine for the June 18, 1945 issue. Mauldin made the cover of the July 21, 1961 issue.

After the war, Mauldin turned to drawing political cartoons expressing a generally civil libertarian view associated with groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union. These were not well received by newspaper editors, who were hoping for apolitical cartoons. Mauldin’s attempt to carry Willie and Joe into civilian life was also unsuccessful, as documented in his memoir Back Home in 1947. In 1951, he appeared with Audie Murphy in the John Huston film The Red Badge of Courage, and in Fred Zinnemann‘s Teresa.[10]

In 1956, he ran unsuccessfully for the United States Congress as a Democrat in New York’s 28th Congressional District. Mauldin said about his run for Congress:

“I jumped in with both feet and campaigned for seven or eight months. I found myself stumping around up in these rural districts and my own background did hurt there. A farmer knows a farmer when he sees one. So when I was talking about their problems I was a very sincere candidate, but when they would ask me questions that had to do with foreign policy or national policy, obviously I was pretty far to the left of the mainstream up there. Again, I’m an old Truman Democrat, I’m not that far left, but by their lives I was pretty far left.”[11]

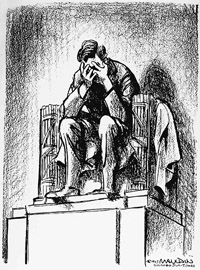

Mauldin’s famous cartoon following the Kennedy assassination

In 1959 Mauldin won a second Pulitzer Prize, while working at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for a cartoon depicting Soviet author Boris Pasternak in a Gulag, asking another prisoner, “I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?”[9]Pasternak had won the Nobel Prize for his novel Doctor Zhivago, but was not allowed to travel to Sweden to accept it. The following year Mauldin won the National Cartoonist Society Award for Editorial Cartooning. In 1961, he received their Reuben Award as well.

In addition to cartooning, Mauldin worked as a freelance writer. He also illustratedmany articles for Life magazine, The Saturday Evening Post,, Sports Illustrated, and other publications. He brought back Joe as a war correspondent, writing letters to the stateside Willie. He made cartoons of Willie and Joe together only in tributes to the “soldiers’ generals”: Omar Bradley and George C. Marshall, after their deaths; for a Life article on the “New Army”; and as a salute to the late cartoonist Milton Caniff.

In 1962, Mauldin moved to the Chicago Sun-Times. One of his most famous post-war cartoons was published in 1963, following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. It depicted the statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, with his head in his hands.[12]

In 1969, Mauldin was commissioned by the National Safety Council to illustrate its annual booklet on traffic safety. These pamphlets were regularly issued without copyright, but for this issue the Council noted that Mauldin’s cartoons were under copyright, although the rest of the pamphlet was not.

In 1985, Mauldin won the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism.[13] Mauldin remained with the Sun-Timesuntil his retirement in 1991.

He was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame on May 19, 1991.[14] On September 19, 2001, Sergeant Major of the Army Jack L. Tilley presented Mauldin with a personal letter from Army Chief of Staff General Eric K. Shinseki, and a hardbound book with notes from other senior Army leaders and several celebrities, including TV broadcasters Walter Cronkite and Tom Brokaw, and actor Tom Hanks. Tilley also promoted Mauldin to the honorary rank of first sergeant.[15]

Mauldin drew Willie and Joe for publication one last time on Veterans Day in 1998 for a Peanuts comic strip, in collaboration with its creator Charles M. Schulz, also a World War II veteran. Schulz signed the strip “Schulz, and my hero…” with Mauldin’s signature underneath.[16]

New Mexico native Mauldin frequently returned to his home state. On at least one occasion he made a few drawings on the wall of the El Paraqua restaurant in Española. The restaurant has since hung frames around these.[17]

Death and legacy[edit]

Mauldin died on January 22, 2003, from complications of Alzheimer’s disease and a bathtub scalding.[18] He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on January 29, 2003.[19] Married three times, he was survived by seven children. (His daughter Kaja had died of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2001.)[3]

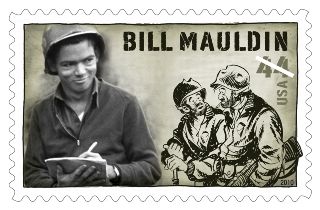

On March 31, 2010, the United States Post Office released a first-class denomination ($0.44) postage stamp in Mauldin’s honor depicting him with Willie & Joe.[20]

In 2005, Mauldin was inducted into the Oklahoma Cartoonists Hall of Fame in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma by Michael Vance. The Oklahoma Cartoonists Collection, created by Vance, is located in the Toy and Action Figure Museum.

Books[edit]

- Star Spangled Banter – 1941

- Sicily Sketchbook – 1943

- Mud, Mules, and Mountains – 1944

- News of the 45th (with Don Robinson) – 1944

- Up Front – 1944

- This Damn Tree Leaks – 1945

- Back Home – 1947

- A Sort of a Saga – 1949

- Bill Mauldin’s Army – 1951

- Bill Mauldin in Korea – 1952

- Up High with Bill Mauldin – 1956

- What’s Got Your Back Up? – 1961

- I’ve Decided I Want My Seat Back – 1965

- Bill of Rights Day Celebration – 1969

- The Brass Ring – 1971

- Name Your Poison – 1975

- Mud and Guts –1978

- Let’s Declare Ourselves Winners and Get the Hell Out – 1985

In April 2008, Fantagraphics Books released a two-volume set of Mauldin’s complete wartime Willie and Joe cartoons, edited by Todd DePastino, titled Willie & Joe: The WWII Years (ISBN 978-1-56097-838-1).

Peanuts[edit]

From 1969 to 1998, cartoonist Charles M. Schulz (himself a veteran of World War II) regularly paid tribute to Bill Mauldin in his Peanuts comic strip on Veterans Day. In the strips, Snoopy, dressed as an army vet, would annually go to Mauldin’s house to “quaff a few root beers and tell war stories.” By the end of the strip Schulz had depicted 17 of Snoopy’s visits. Schulz also paid tribute to Rosie the Riveter in 1976, and Ernie Pyle in 1997 and 1999.[21]

Filmography[edit]

The films Up Front (1951) and Back at the Front (1952) were based on Mauldin’s Willie and Joe characters; however, when Mauldin’s suggestions were ignored in favor of making a slapstick comedy, he returned his advising fee; he said he had never seen the result.[18]

Mauldin also appeared as an actor in the 1951 films The Red Badge of Courage and Teresa, and as himself in the 1998 documentary America in the ’40s. He also appeared in on-screen interviews in the Thames documentary The World at War.[22]

Also here is some information about the 45th Infantry Division.

(I have served with some of these guys. They were some great guys and even better soldiers!)

45th Infantry Division (United States)

| 45th Division 45th Infantry Division |

|

|---|---|

45th Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia.

|

|

| Active | 1920–45 1946–68 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

| Nickname(s) | “Thunderbird”[1] |

| Motto(s) | Semper Anticus (Latin: “Always Forward”)[2] |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Troy H. Middleton Dwight E. Beach Philip De Witt Ginder |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia (1920-46) |  |

| Distinctive unit insignia (1946-68) |  |

The 45th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army, part of the Oklahoma Army National Guard, from 1920 to 1968. Headquartered mostly in Oklahoma City, the guardsmen fought in both World War IIand the Korean War. They trace their lineage from frontier militias that operated in the Southwestern United Statesthroughout the late 1800s.[citation needed]

The 45th Infantry Division guardsmen saw no major action until they became one of the first National Guard units activated in World War II in 1941. They took part in intense fighting during the invasion of Sicily and the attack on Salernoin the 1943 Italian Campaign. Slowly advancing through Italy, they fought in Anzio and in Monte Cassino. After landing in France during Operation Dragoon, they joined the 1945 drive into Germany that ended the War in Europe.

After brief inactivation and subsequent reorganization as a unit restricted to Oklahomans, the division returned to duty in 1951 for the Korean War. It joined the United Nations troops on the front lines during the stalemate of the second half of the war, with constant, low-level fighting and trench warfare against the People’s Volunteer Army of China that produced little gain for either side. The division remained on the front lines in such engagements as Old Baldy Hill and Hill Eerie until the end of the war, returning to the U.S. in 1954.

The division remained a National Guard formation until its inactivation in 1968 as part of a downsizing of the Guard. Several units were activated to replace the division and carry on its lineage. Over the course of its history, the 45th Infantry Division sustained over 25,000 battle casualties, and its men were awarded nine Medals of Honor, twelve campaign streamers, the Croix de Guerre and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation.

History[edit]

With the outbreak of World War I, troops of the National Guard were formed into the units which exist today, with the Colorado Guard forming the 157th Infantry Regiment, the Arizona Guard forming the 158th Infantry Regiment, and the New Mexico Guard forming the 120th Engineer Regiment. These units were attached to the 40th Infantry Division and deployed to France where they were used as “depot” forces to provide replacements for front-line units. They returned home at the end of the war.[3] The Oklahoma Guard units that would later become the 179th Infantry Regiment and 180th Infantry Regiment were assigned to the 36th Infantry Division and would earn a combat participation credit during the Meuse-Argonne Campaign (26 September – 11 November 1918) in France as the 142nd Infantry.[4]

Inter-war years[edit]

1923–1940 “Square” Organization [5]

|

On 19 October 1920, the Oklahoma State militia was organized as the 45th Infantry Division of the Oklahoma Army National Guard, and manned with troops from Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.[6] The division was formed and federally recognized as a National Guard unit on 3 August 1923 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[7] It was assigned the 89th Infantry Brigade of the Colorado and Arizona National Guards, and the 90th Infantry Brigade of the Oklahoma National Guard.[8] As a consequence of these militia roots, when the division was properly organized, many of its members were marksmen and outdoorsmen from the remote frontier regions of the Southwestern United States.[9] The division’s first commander was Major General Baird H. Markham.[10]

The 45th Infantry Division engaged in regular drills but no major events in its first few years, though the division’s Colorado elements were called in to help quell a large coal mining strike.[11] The onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s severely curtailed its funding for training and equipment. Major General Roy Hoffman took command in 1931, followed by Alexander M. Tuthill, Alexander E. McPherren in 1935, and William S. Key in 1936.[10] In 1937, the division’s troops were once again called up, this time to help manage a locustplague affecting Colorado.[11]

Before the 1930s, the division’s symbol was a red square with a yellow swastika, a tribute to the large Native American population in the southwestern United States.

The division’s original shoulder sleeve insignia, approved in August 1924,[12] featured a swastika, a common Native American symbol, as a tribute to the Southwestern United States region which had a large population of Native Americans. However, with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, with its infamous swastika symbol, the 45th Division stopped using the insignia.[13] Following a long process of submissions for new designs, a new shoulder sleeve insignia, designed by a Carnegie, Oklahoma native named Woody Big Bow,[14] featuring the Thunderbird, another Native American symbol, was approved in 1939.[1]

In August 1941, the 45th Infantry Division took part in the Louisiana Maneuvers, the largest peacetime exercises in U.S. military history.[15] It was assigned to VIII Corps with the 2nd Infantry Division and the 36th Infantry Division, camped near Pitkin, Louisiana.[16] Still operating with outmoded equipment from World War I, the division did not perform well during these exercises.[17] With poor weather and bad equipment, the undertrained 45th Infantry Division was criticized by officers who considered it “feeble”.[16] In spite of these deficiencies, less than one month later, the men were recalled to the active duty force, much to their chagrin, because of concerns of an impending American entry into World War II.[15]

World War II[edit]

A monument in Abilene, Texas commemorating the 45th Infantry Division’s time in Texas as it trained at Camp Barkeley in 1940.

On 16 September 1941, the 45th Infantry Division, under Major General William S. Keys, was federalized from state control into the regular army force.[7] It was one of four National Guard divisions to be federalized, alongside the 30th, the 41st and 44th Infantry Divisions, originally for a one-year period.[18] Its men immediately began basic combat training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[19] Throughout 1942, it continued this training at Camp Barkeley, Texas,[20] before moving to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, to undergo amphibious assault training in preparation for an invasion of Italy.[21] It then moved to Pine Camp, New York briefly for winter warfare training, but was hampered by continuously poor weather. In January 1943 it moved to Fort Pickett, Virginia, for its final training.[22] The division, now commanded by Major General Troy H. Middleton, a Regular Army soldier and highly distinguished World War I veteran, moved to the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation‘s Camp Patrick Henry to await combat loading on the transports.[23]

The division’s two combat commands, the 89th and 90th Infantry Brigades, were not activated, as the army favored smaller and more versatile regimental commands for the new conflict.[8] The 45th Infantry Division was instead based around the 157th, 179th, and 180th Infantry Regiments.[24] Also assigned to the division were the 158th, 160th, 171st, and 189th Field Artillery Battalions, the 45th Signal Company, the 700th Ordnance Company, the 45th Quartermaster Company, the 45th Reconnaissance Troop, the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 120th Medical Battalion.[24]

Sicily[edit]

1942–1963 “Triangular” Organization[25]

|

The 45th Division sailed from the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation for the Mediterranean region on 8 June 1943, combat loaded aboard thirteen attack transports and five cargo attack vessels as convoy UGF-9 headed by the communications ship USS Ancon.[21][23] By the time the 45th Division landed in North Africa on 22 June 1943, the Allies had largely secured the African theater. As a result, the division was not sent into combat upon arrival and instead commenced training at Arzew, French Morocco,[26] in preparation for the invasion of Sicily. Allied intelligence estimated that the island was defended by approximately 230,000 troops, the majority of which were drawn mostly from weak Italian formations and two German divisions which had been reconstituted after being destroyed earlier. Against this, the Allies planned to land 180,000 troops,[27] including the 45th Infantry Division, which was assigned to Lieutenant General Omar Bradley‘s II Corps, part of the U.S. Seventh Army under Lieutenant General George S. Patton, for the operation.[28]

The division was subsequently assigned a lead role in the amphibious assault on Sicily, coming ashore on 10 July.[29][30]Landing near Scoglitti, the southernmost U.S. objective on the island, the division advanced north on the U.S. force’s eastern flank.[31] After initially encountering resistance from armor of the Herman Goering Division, the division advanced, supported by paratroopers of the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, part of the 82nd Airborne Division, who landed inland on 11 July.[32] The paratroopers, conducting their first combat jump of the war, then set up to protect the 45th’s flank against German counterattack, but without weapons to counter heavy armor, the paratroopers had to rely on support from the 2nd Armored Division to repulse the German Tiger I tanks.[32] As the division advanced towards its main objective to capture the airfields at Biscari, and Comiso, German forces pushed back.[33] For most of the first two weeks while the division moved slowly north, it encountered only light resistance from Italian forces fighting delaying actions.[34] Italian and German forces resisted fiercely at Motta Hill on 26 July, however, and for four days the 45th Division was held up there.[35] After this, the division was allocated to drive towards Messina, being ordered by the Seventh Army commander to cover the distance as quickly as possible.[36] The 45th Division spent a few days in that city, but on 1 August, the division was withdrawn from the front line for rest and rear-guard patrol duty,[26] after which the division was assigned to Major General Ernest J. Dawley‘s VI Corps, part of the U.S. Fifth Army, under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, in preparation for the invasion of mainland Italy.[37]

Salerno[edit]

On 3 September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allied powers. Hoping to occupy as much of the country as possible before the German Army could react, the U.S. Fifth Army prepared to attack Salerno.[38] On 10 September, elements of the division conducted its second landing at Agropoli and Paestum with the 36th Infantry Division, on the southernmost beaches of the attack.[37] Opposing them were elements of the German 29th Panzergrenadier Division and XVI Panzer Corps.[37] Against stiff resistance, the 45th pushed to the Calore River after a week of heavy fighting.[39] The Fifth Army was battered and pushed back by German forces until 20 September, when Allied forces were finally able to break out and establish a more secure beachhead.[37][40]

On 3 November it crossed the Volturno River and took Venafro.[39] The division had great difficulty moving across the rivers and through the mountainous terrain, and the advance was slow. After linking up with the British Eighth Army, which had advanced from the south, the combined force, under the 15th Army Group, commanded by British General Sir Harold Alexander, was stalled when it reached the Gustav Line.[41] Until 9 January 1944, the division, now under Major General William W. Eagles (replacing Major General Middleton who, struck down with arthritis, was sent to England to command VIII Corps in the Normandy invasion), inched forward into the mountains reaching St. Elia, north of Monte Cassino, before moving to a rest area.[39]

Anzio[edit]

Allied forces conducted a frontal assault on the Gustav Line stronghold at Monte Cassino, and VI Corps, under Major General John P. Lucas from 20 September, was assigned to Operation Shingle, detached from the 15th Army Group to land behind enemy lines at Anzio on 22 January 1944.[42] For this mission, CCA (Combat Command A) of the 1st Armored Division was attached to the 45th Infantry Division.[43] Landing on schedule, VI Corps surprised the Germans, but Major General Lucas’s decision to consolidate the beachhead instead of attacking gave the Germans time to bring the LXXVI Panzer Corps forward to oppose the landings.[42][44]

One regiment of the 45th (the 179th Infantry) went ashore with the landings. In company with the British 1st Infantry Division, they advanced north along the Anzio-Albano road and captured the Aprilia “factory”, but encountered ingrained resistance from German armored units a few miles further on. Lucas then ordered the rest of the division ashore. The 45th Division was deployed on the southeastern side of the beachhead, along the lower Mussolini Canal.[45]

On 30 January 1944, when VI Corps advanced from the beaches, it encountered heavy resistance and took heavy casualties.[42][46] VI Corps was stopped at the “Pimlott Line” (the perimeter of the beachhead), and the fight became a battle of attrition.

The first major German counterattack came in early February, was against the British 1st Division. Two regiments of the 45th (the 179th and 157th Infantry) were sent to the Aprilia sector to reinforce the British. The 179th Infantry and a tank battalion of CCA tried to recapture Aprilia but were repulsed. Lucas then moved the rest of the 45th Division to the left-center of the perimeter, at Aprilia and along the west branch of the Mussolini Canal.[45] For the next few months the 45th Infantry Division was mostly stuck in place, holding its ground during repeated German counterattacks, and subjected to bombardment from aircraft and artillery.[39]

On 16 February, a major German attack struck the 45th, and nearly broke through the 179th Infantry on 18 February. Lucas sent famed U.S. Army Ranger leader Colonel William Orlando Darby to assume command of the 157th Infantry, and the Germans were repulsed.[45] The next three months were spent on the defensive, with the 45th engaged in trench warfare, alike to that in World War I.

On 23 May, VI Corps, now commanded by Major General Lucian Truscott, went on the offensive, breaking out of the beachhead to the northeast, with the 45th Division forming the left half of the attack. By 31 May, the German defenses were shattered, and the 45th Division turned northwest, toward the Alban Hills and Rome.[47] On 4 June the 45th Division crossed the Tiber River below Rome, and entered the city along with other VI Corps troops.[48] Men of the 45th Division were the first Allied troops to reach the Vatican.

On 16 June, the 45th Division withdrew for rest in preparation for other operations.[39] At this time, VI Corps was attached to the Seventh Army, under Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, itself part of the 12th Army Group under Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers.[49] The 45th, 36th, and 3rd Infantry Divisions were pulled from the line in Italy in preparation for Operation Dragoon (formerly Anvil), the invasion of southern France. Dragoon was originally planned to coincide with the Normandy landings in the north, but was delayed until August because of a shortage of landing craft.[50]

France and Germany[edit]

The 45th Infantry Division participated in its fourth amphibious assault landing during Operation Dragoon on 15 August 1944, at St. Maxime, in Southern France.[39] The 45th Infantry Division landed its 157th and 180th regimental combat teams and captured the heights of the Chaines de Mar before meeting with the 1st Special Service Force.[51] The German Army, reeling from the Battle of Normandy, in which it had suffered a major defeat, pulled back after a short fight, part of an overall German withdrawal to the east following the landings.[52][53] Soldiers of the 45th Infantry Division engaged the dispersed forces of German Army Group G, suffering very few casualties.[48] The U.S. Seventh Army, along with Free French forces, were able to advance north quickly. By 12 September, the Seventh Army linked up with Lieutenant General George S. Patton‘s U.S. Third Army, advancing from Normandy, joining the two forces at Dijon.[50] Against slight opposition, it spearheaded the drive for the Belfort Gap. The 45th Infantry Division took the strongly defended city of Epinal on 24 September.[39] The division was then reassigned to V Corps, under the command of Major General Leonard T. Gerow, for its next advance.[49] On 30 September the division crossed the Moselle River and entered the western foothills of the Vosges, taking Rambervillers.[39] It would remain in the area for a month waiting for other units to catch up before crossing the Mortagne River on 23 October.[39] The division remained on the line with the U.S. 6th Army Group the southernmost of three army groups advancing through France.[54]

After the crossing was complete, the division was relieved from V Corps and assigned to Major General Wade H. Haislip‘s XV Corps.[49] The division was allowed a one-month rest, resuming its advance on 25 November, attacking the forts north of Mutzig. These forts had been designed by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1893 to block access to the plain of Alsace. The 45th Division next crossed the Zintzel River before pushing through the Maginot Line defenses.[39] During this time much of the division’s artillery assets were attached to the 44th Infantry Division to provide additional support.[55] The 45th Infantry Division, now commanded by Major General Robert T. Frederick, who had previously commanded the 1st Special Service Force, was reassigned to VI Corps on New Year’s Day.[49] From 2 January 1945, the division fought defensively along the German border, withdrawing to the Moder River.[39] It sent half of its artillery to support the 70th Infantry Division.[55] On 17 February the division was pulled off the line for rest and training. Once this rest period was complete, the division was assigned to XV Corps for the final push into German territory.[49] The 45th moved north to the Sarreguemines area and smashed through the Siegfried Line, on 17 March taking Homburg on the 21st and crossing the Rhine between Worms and Hamm on the 26th.[39] The advance continued, with Aschaffenburg falling on 3 April, and Nuremberg on the 20th.[39] The division crossed the Danube River on 27 April, and liberated 32,000 captives of the Dachau concentration camp on 29 April 1945.[39] The division captured Munich during the next two days, occupying the city until V-E Day and the surrender of Germany.[56] During the next month, the division remained in Munich and set up collection points and camps for the massive numbers of surrendering troops of the German armies. The number of POWs taken by the 45th Division during its almost two years of fighting totalled 124,840 men.[39] The division was then slated to move to the Pacific theater of operations to participate in the invasion of mainland Japan on the island of Honshu, but these plans were scrubbed before the division could depart after the surrender of Japan, on V-J Day.[57]

Casualties[edit]

- Total battle casualties: 20,993[58]

- Killed in action: 3,547[58]

- Wounded in action: 14,441[58]

- Missing in action: 478[58]

- Prisoner of war: 2,527[58]

Criminal allegations[edit]

After the war, courts-martial were convened to investigate possible war crimes by members of the division. In the first case, dubbed the Biscari massacre, American troops from C Company, 180th Infantry Regiment, were alleged to have shot 74 Italian and two German prisoners in Acate in July 1943 following the capture of an airfield in the area. Lieutenant General George Patton, the Seventh Army commander, asked Major General Omar Bradley, commanding II Corps, to get the case dismissed to prevent bad press, but Bradley refused. A non-commissioned officer later confessed to the crimes and was found guilty, but an officer who claimed he had only been following orders was acquitted.[59][60][61]

Dead German troops near Dachau Concentration Camp, allegedly killed in the Dachau massacre in 1945.

In a second incident, the Army considered court-martialling several officers of the 157th Infantry Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Felix L. Sparks after servicemen were accused of massacring German soldiers who were surrendering at the Dachau concentration camp in 1945. Some of the German troops were camp guards; the others were sick and wounded troops from a nearby hospital. The soldiers of the 45th Division who liberated the camp were outraged at the malnourishment and maltreatment of the 32,000 prisoners they liberated, some barely alive, and all victims of the Holocaust. After entering the camp, the soldiers found boxcars filled with dead bodies of prisoners who had succumbed to starvation or last-minute executions, and in rooms adjacent to gas chambers they found naked bodies piled from the floor to the ceiling.[62] The cremation ovens, which were still in operation when the soldiers arrived, contained bodies and skeletons as well. Some of the victims apparently had died only hours before the 45th Division entered the camp, while many others lay where they had died in states of decomposition that overwhelmed the soldiers’ senses.[63] Accounts conflict over what happened and over how many German troops were killed. After investigating the incident, the Army considered court-martialling several officers involved, but Patton successfully intervened. Seventh Army was being disbanded and Patton had been appointed Military Governor of Bavaria, placing the matter in his hands.[64] Some veterans of the 45th Infantry Division have said that only 30 to 50 German soldiers were killed and that very few were killed trying to surrender, while others have admitted to killing or refusing to treat wounded German guards.[65]

After the war[edit]

Callsigns of the 45th Division [66][67]

Battalions of the Infantry Regiments

Regimental Tanks and Mortars

|

During World War II, the 45th Division fought in 511 days of combat.[26] Nine soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor during their service with the 45th Infantry Division: Van T. Barfoot,[68] Ernest Childers,[69] Almond E. Fisher,[70] William J. Johnston,[71] Salvador J. Lara,[72] Jack C. Montgomery,[73] James D. Slaton,[69] Jack Treadwell,[74] and Edward G. Wilkin.[75] Soldiers of the division also received 61 Distinguished Service Crosses, three Distinguished Service Medals, 1,848 Silver Star Medals, 38 Legion of Merit medals, 59 Soldier’s Medals, 5,744 Bronze Star Medals, and 52 Air Medals. The division received seven distinguished unit citations and eight campaign streamers during the conflict.[26]

Most of the division returned to New York in September 1945, and from there went to Camp Bowie, Texas. On 7 December 1945, the division was deactivated from the active duty force and its members reassigned to other Army units. The following year, on 10 September 1946, the 45th Infantry Division was reconstituted as a National Guard unit.[76] Instead of comprising units from several states, the post-war 45th was an all-Oklahoma organization.[77] During this time the division was also reorganized and as a part of this process the 157th Infantry was removed from the division’s order of battle and replaced with the 279th Infantry Regiment.[78]

During this time, the U.S. Army underwent a drastic reduction in size. At the end of World War II, it contained 89 divisions, but by 1950, there were just 10 active divisions in the force, along with a few reserve divisions such as the 45th Infantry Division which were combat-ineffective.[79] The division retained many of its best officers as senior commanders as the force downsized, and it enjoyed a good relationship with its community. The 45th in this time was regarded as one of the better-trained National Guard divisions.[80] Regardless, by mid-1950 the division had only 8,413 troops, less than 45 percent[n 1] of its full-strength authorization.[81] Only 10 percent of the division’s officers and 5 percent of its enlisted men had combat experience with the division from World War II.[82]

Korean War[edit]

At the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the U.S. Army looked to expand its force again to prepare for major conflict. After the North Korean People’s Army invaded the Republic of Korea four understrength U.S. divisions on occupation duty in Japan were rushed to South Korea to stand alongside the Republic of Korea Army. These were the 7th Infantry Division, the 1st Cavalry Division, the 24th Infantry Division, and the 25th Infantry Division, which were all under the control of the Eighth United States Army. Due to drastic reductions in U.S. military spending following the end of World War II, these divisions were equipped with worn-out or obsolete weaponry and suffered from a shortage of anti-armor weapons capable of penetrating the hulls of the North Korean T-34 tanks.[83][84]

Reinforcement pool[edit]

Initially, the division was used to provide a pool of reinforcements for the divisions which had been sent to the Korean War theater, and in January 1951 it provided 650 enlisted fillers for overseas service. Later that month, it was given 4,006 new recruits for its three infantry regiments and artillery assets, and each unit created a 14-week training program to prepare these new soldiers for combat.[85] Because of heavy casualties and slow reinforcement rates, the Army looked to the National Guard to provide additional units to relieve the beleaguered Eighth Army. At the time, the 45th Infantry Division was comprised overwhelmingly of high school students or recent graduates and only about 60 percent of its divisional troops had conducted training and drills with the division for a year or more. Additionally, only about 20 percent of its personnel had prior experience of military service from World War II.[86] Nevertheless, the division was one of four National Guard divisions identified as being among the most prepared for combat based on the effectiveness of its equipment, training, and leadership.[87] As a result, in February 1951, the 45th Infantry Division was alerted that it would sail for Japan.[88]

In preparation for the deployment, the division was sent to Fort Polk, Louisiana, to begin training and to fill its ranks.[89]After its basic training was complete, the division was sent to Japan in April 1951 for advanced training and to act as a reserve force for the Eighth United States Army, then fighting in Korea.[90] The involvement of the National Guard in the fighting in Korea was further expanded when the 40th Infantry Division of the California Army National Guard received warning orders for deployment as well.[91]

Initial struggles[edit]

On 1 September 1951, the 45th Infantry Division was activated as the first National Guard division to be deployed to the Far East theater since World War II.[89][92] Nevertheless, it was not deployed to Korea until December 1951, when its advanced training was complete.[90][93] Following its arrival, the division moved to the front line to replace the 1st Cavalry Division, who were then delegated to the Far East reserve, having suffered over 16,000 casualties in less than 18 months of fighting.[94]

Though the 45th remained de facto segregated as an all-white unit in 1950,[95]individual unit commanders went to great lengths to integrate reinforcements from different areas and ethnicity into their units.[96] By 1952, it was fully integrated.[97]Additionally, in an effort to reduce the burden on the National Guard,[n 2] troops from the division were often replaced by enlisted and drafted soldiers from the active duty force. When it arrived in Korea, only half the division’s manpower were National Guard troops, and over 4,500 guardsmen left between May and July 1952, continually replaced by more active duty troops, including an increasing number of African Americans.[98] Though the division was no longer an “All-Oklahoma” unit, leaders opted to keep its designation as the 45th Infantry Division.[99][n 3]

By the time the division was in place, the battle lines on both sides had largely solidified, leaving the 45th Infantry Division in a stationary position as it conducted attacks and counterattacks for the same ground.[100] The division was put under the command of Eighth Army’s I Corps for most of the conflict.[101] It was deployed around Chorwon and assigned to protect the key routes from that area into Seoul. The terrain was difficult and the weather was poor in the region.[102] The division suffered its first casualty on 11 December 1951.[103]

Initially, the division did not fare well, though it improved quickly.[90] Its anti-aircraft and armor assets were used as mobile artillery, which continuously pounded Chinese positions. The 45th, in turn, was under constant artillery and mortar attack.[104] It also conducted constant small-unit patrols along the border seeking to engage Chinese outposts or patrols. These small-unit actions made up the majority of the division’s combat in Korea.[105] Chinese troops were well dug-in and better trained than the troops of the inexperienced 45th, and it suffered casualties and frequently had to disengage when it was attacked.[106]

In the division’s first few months on the line, Chinese forces conducted three raids in its sector. In retaliation, the 245th Tank Battalion sent nine tanks to raid Agok.[100] Two companies of Chinese forces ambushed and devastated a patrol from the 179th Infantry a short time later.[100] In the spring, the division launched Operation Counter, which was an effort to establish 11 patrol bases around Old Baldy Hill. The division then defended the hill against a series of Chinese assaults from the Chinese 38th Army.[100]

Final engagements and the end of the war[edit]

The 45th Infantry Division, along with the 7th Infantry Division, fought off repeated Chinese attacks all along the front line throughout 1952, and Chinese forces frequently attacked Old Baldy Hill into the fall of that year.[107] Around that time, the 45th Infantry Division relinquished command of Old Baldy Hill to the 2nd Infantry Division. Almost immediately the Chinese launched a concentrated attack on the hill, overrunning the U.S. forces.[108] Heavy rainstorms prevented the divisions from retaking the hill for around a month, and when it was finally retaken it was heavily fortified to prevent further attacks.[109] The 245th Tank Battalion was sent to assault Chinese positions throughout late 1952, but most of the division held a stationary defensive line against the Chinese.[107]

In early 1953, North Korean forces launched a large-scale attack against Hill 812, which was then under the control of K Company, 3rd Battalion, 179th Infantry.[110]The ensuing Battle of Hill Eerie was one of a series of larger attacks by Chinese and North Korean forces which produced heavier fighting than the previous year had seen. These offensives were conducted largely in order to secure a better position during the ongoing truce negotiations.[110] Chinese forces continued to mount concentrated attacks on the lines of the UN forces, including the 45th Infantry Division, but the division managed to hold most of its ground, remaining stationary until the end of the war in the summer of 1953.[111]

During the Korean War the 45th Infantry Division suffered 4,004 casualties, consisting of 834 killed in action and 3,170 wounded in action.[90] The division was awarded four campaign streamers and one Presidential Unit Citation.[112] One soldier from the division, Charles George, was awarded the Medal of Honor while serving in Korea.[113]

After Korea[edit]

Soldiers of the 45th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, the successor organization to the 45th Infantry Division, hold a ceremony ahead of a deployment to Operation Enduring Freedom in February 2011.

The division briefly patrolled the Korean Demilitarized Zone following the signing of the armistice ending the war, but most of its men returned home and reverted to National Guard status on 30 April 1954.[76] Its colors were returned to Oklahoma on 25 September of that year, formally ending the division’s presence in Korea.[99]

The division remained as a unit of the Oklahoma National Guard, and participated in no major actions throughout the rest of the 1950s save regular weekend and summer training exercises. In 1963, the formation was reorganized in accordance with the Reorganization Objective Army Divisions plan, which saw the establishment of a 1st, 2nd and 3rd Brigade within the division. These brigades would see no major deployments or events, and were deactivated five years later in 1968.[114] That same year, due to the perceived lack of need for so many large formations in the Army National Guard, the 45th Infantry Division was deactivated, as part of a larger move to reduce the number of Army National Guard divisions from 15 to eight, while increasing the number of separate brigades from seven to 18.[115] In its place, the independent 45th Infantry Brigade (Separate) was established.[76][116] The 45th Infantry Brigade received all of the 45th Division’s lineage and heraldry, including its shoulder sleeve insignia.[2] Also activated from division assets were the 45th Field Artillery Group, later redesignated the 45th Fires Brigade, and the 90th Troop Command.[117][118]

Honors[edit]

The 45th Infantry Division was awarded eight campaign streamers and one unit award in World War II and four campaign streamers and one unit decoration in the Korean War, for a total of twelve campaign streamers and two unit decorations in its operational history.[7]

| Conflict | Streamer | Inscription | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| French Croix de Guerre, World War II (With Palm) | Embroidered “Acquafondata“ | 1943–1944 | |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Streamer | Sicily (with Arrowhead) | 1943 | |

| Naples–Foggia (with Arrowhead) | 1943 | ||

| Anzio (wirth Arrowhead) | 1943 | ||

| Rome–Arno | 1944 | ||

| Southern France (with Arrowhead) | 1944 | ||

| Rhineland | 1944–1945 | ||

| Ardennes–Alsace | 1944–1945 | ||

| Central Europe | 1945 | ||

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | For service in Korea | 1952–1953 | |

| Korean Service Campaign Streamer | Second Korean Winter | 1951–1952 | |

| Korea, Summer–Fall 1952 | 1952 | ||

| Third Korean Winter | 1952–1953 | ||

| Korea, Summer 1953 | 1953 |

Commanding Generals[edit]

| MG | Baird H. Markham | 15 Feb 1923 | 6 Apr 1931 |

| MG | Roy V. Hoffman | 13 Jun 1931 | 13 Jun 1933 |

| MG | Alexander M. Tuthill | 14 Jun 1933 | 21 Oct 1935 |

| MG | Charles E. McPherren | 25 Nov 1935 | 29 Jul 1936 |

| MG | William S. Key | 29 Jul 1936 | 13 Oct 1942 |

| MG | Troy H. Middleton | 14 Oct 1942 | 21 Nov 1943 |

| MG | Marion L. Finley | 20 Nov 1943 | 23 Nov 1945 |

| MG | William W. Eagles | 22 Nov 1943 | 30 Nov 1944 |

| MG | Robert T. Frederick | 1 Dec 1944 | 10 Sep 1945 |

| BG | H.J.D. Meyer | 11 Sep 1945 | 7 Dec 1945 |

| MG | James C. Styron | 5 Sep 1946 | 20 May 1952 |

| MG | David Ruffner | 21 May 1952 | 15 Mar 1953 |

| MG | Philip De Witt Ginder | 16 Mar 1953 | 30 Nov 1953 |

| MG | Paul D. Harkins | 1 Dec 1953 | 15 Mar 1954 |

| BG | Harvey H. Fischer | 18 Mar 1954 | 27 Apr 1954 |

| MG | Hal L. Muldrow, Jr | 10 Sep 1952 | 31 Aug 1960 |

| MG | Frederick Alvin Daugherty | 1 Sep 1960 | 20 Nov 1964 |

| MG | Jasper N. Baker | 21 Nov 1964 | 31 Jan 1968 |

Note: Similarity of dates for General Muldrow and commanders beginning with General Ruffner is because 45th Infantry Division, AUS, was retained in Korea while twin unit, 45th Infantry Division, NGUS, was activated in Oklahoma.[119]