|

Oregon’s Only No Compromise Gun Rights Organization |

| 12.06.17

Today the “National Reciprocity Act” passed the US House on a 231-198 vote.

While national reciprocity would be a good thing for gun owners, and override Oregon’s ridiculous refusal to recognize a single other state’sconcealed handgun license, the bill was coupled with terrible legislation dubbed “Fix NICS”.

Unfortunately “Fix NICS” vastly expands the flawed and failed Brady background check law and will no doubt ensnare many more people who will be denied their right to purchase a firearm as a result of faulty background checks.

“Fix NICS” was supported by anti-gun organizations as well as NRA and National Shooting Sports Foundation, always a troubling alliance.

Ultimately no amount of legislation is going to change the fact that human error is responsible for the mess that the background check system is.

Now many people who are in no way dangerous or “criminal” are going to be added to the list of prohibited people. Nothing in the legislation provides any recourse for persons falsely denied.

The bill faces a very uncertain future in the Senate where it is quite possible that the reciprocity language could be stripped out leaving us with only more gun control.

It that happens, when the bill goes back to the House, the supporters of reciprocity will have a hard time opposing the new gun control they voted for.

|

You probably don’t know Tim Eaton. He’s a Kentucky preacher who can skin a buck, call a turkey, catch a bass, and hold his own in just about any outdoor pursuit you care to name.

But to people in these parts, he’s best known as a coyote hunter. He shoots 30 to 40 big eastern dogs each winter using nothing but his hand calls and an old Savage rifle.

After hunting with him last year, I learned that his success comes from following a few fundamental rules.

1. Be Persistent Most eastern coyote hunters are all too familiar with the sting of defeat. Eaton and I hunted a full week last February before we shot a coyote. In this part of the world, that’s not terribly unusual—though admittedly, we had tougher-than-normal conditions. If you want to be a coyote hunter in the East, you have to persevere through the dead sets.

2. Play the Wind “The most critical thing for the setup, in my mind, is the wind,” Eaton says. “I may know there is a coyote there, but if the wind isn’t right when I’m planning to hunt, I’m just not going to go in. Ninety percent of the time, that dog is going to smell you before you see it. It’s just as important to play the wind getting to where you want to hunt, too. If the wind is carrying your scent toward them, they’re already gone before you make the first sound.”

2. Play the Wind “The most critical thing for the setup, in my mind, is the wind,” Eaton says. “I may know there is a coyote there, but if the wind isn’t right when I’m planning to hunt, I’m just not going to go in. Ninety percent of the time, that dog is going to smell you before you see it. It’s just as important to play the wind getting to where you want to hunt, too. If the wind is carrying your scent toward them, they’re already gone before you make the first sound.”

3. Be Ready for Warm Weather In the Southeast, 50-degree-plus days are common throughout the wintertime. That makes the hunting tougher—but it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t go. “They don’t usually move as late when it’s warm,” Eaton says. “And generally, they’ll bed up on thicket edges where they can catch a good breeze and lay in the shade. The opposite is true on really cold days. Coyotes will bed deeper in cover, out of the wind.”

4. Respect the Setup Many eastern hunters miss seeing responding coyotes due to the rolling terrain and dense cover. “It’s good to know how your land lays. Knowing what is within a half mile of you will help determine from what direction those dogs are going to approach you,” Eaton says. He suggests setting up within 400 to 500 yards of a suspected coyote bed. Get too close and you risk bumping dogs. Set up too far away and they’ll never commit. He also encourages in-depth analysis of the terrain before making the first calls. “If you don’t set up to where you can see over a break or down each side of a point, coyotes will come in and you’ll lose them, with no idea where they’ll pop up at,” Eaton says.

5. Sound Scared Eaton uses distress calls 95 percent of the time, but he does change up his sounds. “Generally, I’ll start out soft and then work my way up in volume from there,” he says. “I call in 30- to 60-second sequences. After eight or 10 minutes, I’ll go to a much louder call. You can change the pitch by where you’re at on the reed, and the volume by the length of the horn (your hand positioning) on the call.”

6. Get Ground Eastern hunters deal with fewer coyotes, smaller properties, more hunting pressure, and tougher terrain than western hunters. Because of that, to stay persistent and follow rule No. 1, you need plenty of ground to hunt. “Having access to a lot of land is a great benefit because you can’t go into the same territory day after day or week after week,” Eaton says. Fortunately, it’s usually easy to get predator-hunting access. “Many property owners and farmers won’t let you in during deer or turkey season, but they will let you hunt coyotes at other times of the year,” he says. “Take care of the land and treat the property owners right. Do that, and most of them will let you come in and coyote hunt.”

When you really want to send a message. Then use the 300 Win magnum round down range!

The USS California

USS Oklahoma

USS Oklahoma

The USS Arizona

USS Nevada

USS Nevada

USS West Virginia

USS Maryland

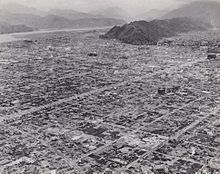

And here is what it got the Empire of Japan in the long run. This was a major city in Japan in 1945

This was a major city in Japan in 1945

Ditto

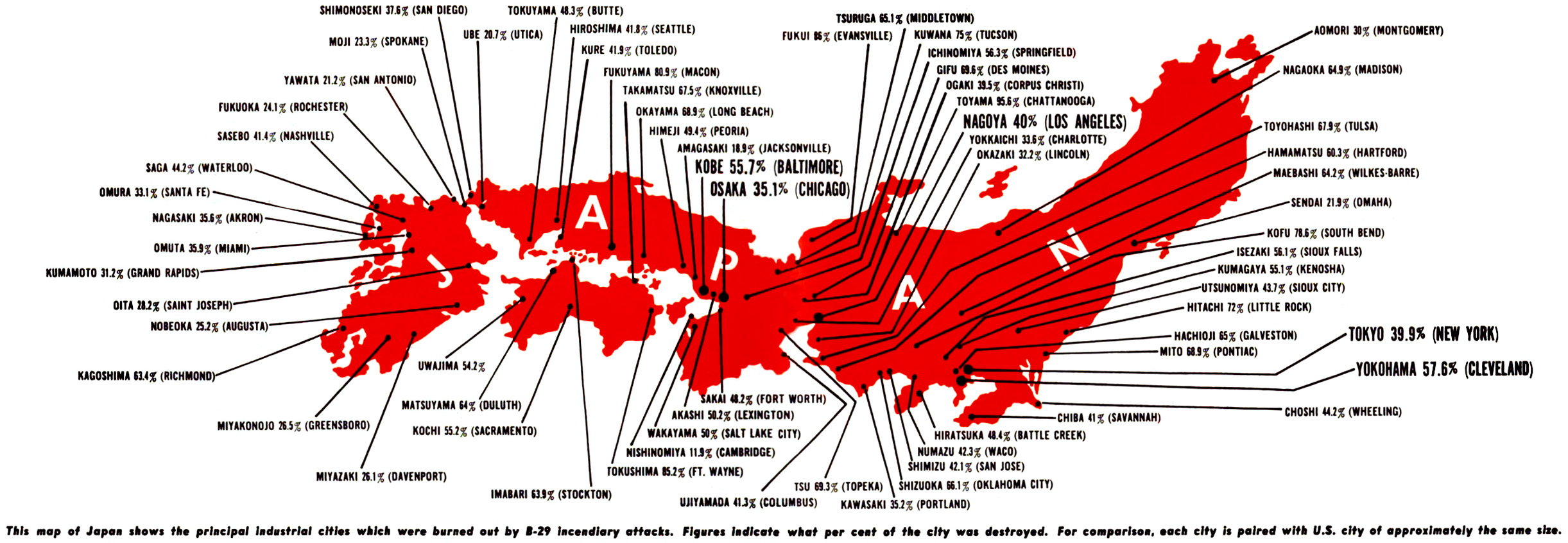

I also found this and thought it was interesting. It is an Air Force Map of Cities in Japan that we wiped off the face of the earth. Let us hope that stuff never happens again!

It is an Air Force Map of Cities in Japan that we wiped off the face of the earth. Let us hope that stuff never happens again!

When the bloody tide of communism started rolling across the Black Continent in the 1960’s, the Western world preferred to sit and watch, or even assist it. The astute few, however, quickly realized that this seemingly chaotic surge had a clear purpose: to drive the white man out of Africa and make it a foothold of third world hordes. And even though the white man was greatly outnumbered, with hands tied by political treachery and cowardice, there still were plenty who stood and fought in an epic struggle that continues to this day.

After major colonial powers’ withdrew from Africa, the only white players left were Portugal, Rhodesia and South Africa. Made complacent by years of peace and comfort, Portuguese colonial administration could do little to stop Angola and Mozambique from rapidly corkscrewing into oblivion; toppling of Salazar’s regime in Portugal by communists simply delivered the coup de grace. Mozambique became a typical African dictatorship, while Angola was split between three armed groups: MPLA, UNITA and FNLA.

South Africa, realizing it was next on the menu, started supporting UNITA and especially FNLA against MPLA, which was heavily backed by USSR and especially Cuba. Unfortunately, MPLA still managed to assume power in Angola, and it was not long before it found a new target: South West Africa, a mineral-rich protectorate of South Africa.

The South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO), initially the runt of the Afro-Marxist litter that survived on meager handouts from the Eastern Bloc and treasonous Western governments, started gradually gaining power. In 1972, political opossums in the UN granted it recognition and in 1976, MPLA allowed SWAPO to use its bases in southern Angola as staging grounds for incursions into South West Africa.

Modus operandi of SWAPO wasn’t any different from other black-and-red terrorist groups of their time: infiltrate a remote farming area across the border, murder any whites encountered, torch a farm or two and run back. Arn Durand’s autobiography sums them up perfectly:

Fill your head with Marxist communist ideologies. Pick up an RPG-7, an AK-47 and some landmines and hand grenades, put on a Cuban or Chinese camouflage uniform and march across the border of another country. Shoot and kill the locals who don’t support your ideas. Abduct the schoolchildren at gunpoint, march them to your training bases to indoctrinate them and fill their heads with your bullshit to force them to do what you are doing. You’re looking for shit and you’re bound to get your head blown off and those crap ideas spilt out all over the fine white sand.

– “Zulu Zulu Golf”, 2011

Ovamboland, the northernmost part of South West Africa, rapidly became a battlefield, with its native Ovambo tribe splitting into anti- and pro-SWAPO factions – the former determined to maintain the comfortable status quo under an administration loyal to South Africa, the latter intending to help drive the whites out of “Namibia” and seize power over it.

South Africa reacted quickly, dispatching its army to guard the Angolan-SWA border. But SADF, despite being very adept at conventional warfare, lacked the flexibility needed to intercept SWAPO raiding parties, not to mention that at the time it was not allowed to cross the Angolan border. Invading guerrillas could only be tackled by something much swifter and far less hierarchical than the army – something that South Africa did not have.

Securing the full length of the Angolan-SWA border required tens of thousands of troops.

The solution came in 1978, with arrival of Johannes “Sterk Hans” Dreyer, a South African Police brigadier, in the area of operations. Having served in Rhodesia in the period when SAP assisted it with counter-insurgency efforts, he knew how the country’s most fearsome military unit, the Selous Scouts, operated. While recognizing the usefulness of local population for intelligence gathering, he dismissed the Scouts’ infiltration tactics as unsuitable for the flat, nearly featureless landscape of Ovamboland.

Instead, he opted for a highly mobile hunter-killer unit that would track and pursue guerrillas across immense distances. Operating on a shoestring budget, Dreyer managed to recruit 60 Ovambos and 6 white police officers to man two pickups and two cars, arming them with trophy weapons. His detractors were in stitches over this ragtag outfit, but quickly went silent when in 1979, after seven days of pursuit, it intercepted a terrorist warband, killing two. This was soon followed by another long chase and more dead terrorists; in less than a year, Dreyer’s men were killing 50 to 80 SWAPO per month.

Johannes Dreyer, founder and father figure of Koevoet

But the unit’s official recognition was still far away; until then, “Ops K” sustained itself in any way it could, including by stealing supplies and equipment from military bases. Moreover, the unit’s classified status meant that all their kills were credited to the army; these two circumstances paved the way to mutual resentment that sometimes bordered on open hostility. Three years later, Dreyer went to the higher-ups with statistics. Despite the massive military presence at the Angolan border, Ops K had more enemy contacts and kills than all of the deployed units combined. Backed into a corner by undeniable facts, the MoD finally started coughing up money.

The first sign of the government’s goodwill was a batch of Hippo APCs, intended to counter SWAPO’s copious use of landmines. Dreyer’s men showed their gratitude in a very unorthodox way – by using arc welders and angle grinders to make Hippos open-topped, add gunports, and install weapon mounts that could accommodate even 20mm cannons. Engineers back in SA were horrified, but later ended up incorporating the modifications into new MRAP vehicles: the Army got the Buffel, while Koevoet, as Ops K came to be known, got the Casspir.

This machine pretty much defined the unit’s tactics. Koevoet was split into battlegroups, each comprised of approximately 40 Ovambos, 4 whites, 4 Casspirs bristling with weapons and a Blesbok supply vehicle. The groups patrolled the bush in week-long shifts, visiting villages and inquiring about SWAPO sightings. The moment spoor was picked up, the hunt was on: Ovambos would run in front, pointing out the spoor with long sticks, with Casspirs following closely behind, gunners on top watching for ambushes.

When the enemy was close but not yet visible, a Casspir or two would often leap-frog ahead of the main group in order to prevent them from scattering or cut off a possible escape route. The moment a contact was made, trackers would hit the ground while Casspirs rushed in, encircling the enemy in a hail of gunfire and bursts of white phosphorus grenades. In case of casualties or overwhelming enemy presence, helicopters would be scrambled from a nearby airfield, providing additional firepower and vision; Koevoet’s relationship with the Air Force was far more amiable than with the Army.

Even by African standards, Koevoet was an anomaly. If carrying out military operations as a desegregated police unit in an apartheid state was not enough, the unorthodox tactic they employed put them at extreme risk. Casspirs, while bullet- and mine-proof, offered no protection from RPGs, and their open-topped design made gunners very vulnerable during contacts, while trackers were not protected at all.

Koevoet frequently disregarded the army’s combat zone designations, which resulted in several friendly fire incidents. Another distinguishing feature was the bounty system – the unit was compensated for every killed and captured terrorist, as well as their weapons and equipment, leading to cutthroat competition between battlegroups.

Koevoet also engaged in an improvised hearts-and-minds campaign by treating local natives with great cordiality and protecting them from SWAPO raids; this sharply contrasted with their habit of decorating bumpers and wheels of their Casspirs with corpses as a warning to SWAPO sympathizers. Some Koevoet trackers were ex-SWAPO themselves: similarly to the Selous Scouts, particularly skilled captives were offered to join the battlegroups, while others were gainfully employed as farm workers and cooks. Most of the fighting, however, was still done by whites, as many Ovambos refused to or were simply afraid to participate in contacts.

Each Koevoet Casspir was an arsenal on wheels.

Resourcefulness and sheer brutality of the new unit paid off: despite constant attempts by SWAPO to terrorize South West Africa’s population, very few succeeded and none were left unavenged. The full list of Koevoet operations is far too long to provide here (especially considering that most started as routine patrols), but it is crowned by their defense of Tsumeb, when over 150 SWAPO on their way to a small mining town were intercepted, dispersed and annihilated by several battlegroups before the Army even started to react. The few captives later confessed to being ordered to burn Tsumeb to the ground.

In its prime, SWAPO was a force to be reckoned with. Armed by Soviets, trained by Cubans and brainwashed into extreme bloodthirst, they were a formidable foe even for SADF, one of the most capable armies in the world. And yet, Koevoet did not even bother with posting sentries during their overnight camps in the bush – their reputation did the job just as well.

For SWAPO, the South African Army represented pure evil, but it was a familiar, comprehensible evil. However, hearing the unmistakable roar of a Casspir’s engine and catching a glimpse of a Koevoet constable’s olive uniform was often all it took for a trained guerrilla to panic and flee. Not even 32 Battalion instilled such dread – the idea of an enemy that chases you until you drop dead was far more terrifying than any ambush, and mercy was not guaranteed even in case of surrender.

After South Africa told the UN to scram and allowed its troops to cross into Angola, syringes with benzedrine became standard issue for terrorists, whose survival now hinged on beating Koevoet to their bases deep within Angola rather than just the border. Few ever succeeded – Ovambos’ tracking skills, which they learned from early childhood as herdboys, bordered on supernatural, and Casspirs were never far behind.

The facts speak for themselves: 11 years, 1615 contacts with the enemy, 3681 terrorists killed and captured, 153 constables dead and 949 wounded. That’s a 25:1 kill ratio, compared to the SADF average of 11:1, not to mention that total number of Koevoet staff never exceeded 1000.

Koevoet veterans gather to pay respects to their fallen comrades-in-arms. Pretoria, 2013.

For an outsider, Koevoet were barbarians – grubby, bellicose and completely ruthless. Apartheid South Africa was the favorite boogieman of both communist East and subverted West; once existence of Koevoet was revealed, it also became a target. The very people who bled to ensure that population of South West Africa slept tight at night were described as depraved butchers by politicians and journalists who never stepped foot outside their sterile offices.

Koevoet was disbanded in 1989, its veterans either finding new occupations or becoming scattered across the world as private security contractors. Contemporary governments of Namibia and South Africa prefer to ignore them altogether – given the African tradition of exterminating all opposition, it could be worse.

The outcome of the Border War itself remains unclear: while South Africa failed to retain South West Africa, it bled SWAPO into total impotence, preventing them from establishing yet another bloody dictatorship and forcing them to adhere to more or less democratic means of maintaining power. Modern Namibia owes its peace and stability to Koevoet, SADF and sacrifices they made back in the day, no matter how hard its government tries to deny it.

Some other information about these folks:

| Koevoet Operation K Police Counter-Insurgency Unit |

|

Koevoet Memorial at the Voortrekker Monument, Pretoria |

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | January 1979 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Dissolved | November 1989 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Type | Paramilitary |

| Jurisdiction | |

| Headquarters | Oshakati, Oshana Region |

| Employees | 1,000 (c. 1985) |

| Ministers responsible | |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | |

The Koevoet ([ˈkufut], translated to crowbar, abbreviated Operation K or SWAPOL-COIN) was a major paramilitary police organisation under South African-administered South West Africa, now the Republic of Namibia.

It was an active belligerent in the Namibian War of Independence from 1979 to 1990 – “Crowbar” being a popular allusion to successful attempts at prying insurgents from the local population.[1]

Created by South African Police Brigadier Hans Dreyer, a veteran of the Rhodesian Bush War, the unit’s initial directive was to conduct internal reconnaissance.[2]

Koevoet quickly became one of the most effective combat forces deployed against the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) during the war.[3][4]

Consisting of some 250 white and 800 black Ovambo operators, it has also been held responsible for committing human rights violationsagainst civilians.[5]

After killing or capturing some 3,225 guerrillas and fighting an estimated 1,615 engagements,[6] Koevoet, along with the South West Africa Police, was disbanded in Namibia after 1989.[5]

[hide]

At the end of World War I, the former German South West Africa was granted to South Africa as a mandated territorythrough the League of Nations.

By the 1960s, however, much of Africa was embroiled in a struggle for independence from colonial powers such as Belgium, Great Britain, France, and Portugal.

In the southern subcontinent, where many indigenous tribes had been pushed off their lands by settled Europeans, the political situation was particularly explosive.[7]

Then governed by its apartheid administration, South Africa watched with concern as low intensity conflicts and guerrilla warfare in neighbouring countries ousted traditional white regimes, often replacing them with Marxist-oriented single party states such as those in Zambia, Angola, and Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia).[7][8]

Determined to prevent South West Africa from following this example, South African authorities stepped up their efforts to retain control over their protectorate.

When the League of Nations was dissolved with World War II and replaced by the United Nations in 1945, Pretoria refused to recognise the new Trusteeship Council for mandates. Instead, Jan Christiaan Smuts‘ administration insisted on the right to annexation.

In 1950, the UN confirmed that South Africa’s legal administration was still in force and that it could not compel the latter to open a new trusteeship agreement.[7]

Even after the General Assembly assumed its powers as successor to the League and revoked the mandate in 1966, South West Africa remained a de facto “fifth province” of its larger neighbour.[5][9]

The Namibian Independence War initiated when the South West African People’s Organization commenced its armed struggle against what it termed an illegal occupation of South West Africa.[10]

Disappointed that the UN had failed to take executive action to ensure independence, SWAPO, a prominent independentist group, declared from its Tanzania offices that “We have no alternative but to rise in arms and bring about our liberation.”[7]

This did not come as a surprise to many observers, who pointed out that as early as 1962 the party had already announced that violence was necessary as part of an overall strategy seeking change – a decision which allowed authorities to brand known members as terrorists.[5]

On 26 August 1966, the first military engagement was fought when armed guerrillas clashed with the South African Policein Ovamboland.

A month later, a second SWAPO raid was attempted on a major administrative complex in Oshikango.[7]

South Africa soon found herself confronted with frequent attacks on tribal heads, government installations, and Grootfontein farming regions – the last of these targets in particular caused consternation among white South West Africans.[7]

By 1971, the International Court of Justice had ruled South Africa’s occupation of South West Africa to be illegal under international law.[11]

At this point, SWAPO was the most effective nationalist group in the territory. It enjoyed thorough support from South West Africa’s largest tribe, the Ovambo, and partisans active with its military wing (self-styled the “People’s Liberation Army Namibia“) were often indistinguishable from the local population.[5]

From the South African perspective, combating PLAN was part of a counter-terrorist initiative against those who were viewed as pawns of international communism.[12]

However, the world community increasingly took the opinion that the conflict was a legitimate bid for national liberation; UN officials unilaterally recognised SWAPO as the “sole authentic representative of the Namibian people” and “the future government of Namibia”.[8]

Atrocities were already being charged by both sides, with Pretoria condemning SWAPO’s systematic attacks on basic infrastructure and indiscriminate use of land mines.

The latter retaliated in 1973 by drawing attention to the mistreatment of nationalists in military detention.[12]

Fierce fighting eventually drove ten percent of South West Africa’s population into exile; 69,000 citizens crossed the border into Angolan territory, while another 5,000 fled to Zambia.

Among these refugees were potential SWAPO recruits who subsequently sought insurgent training in Arab Africa, the Soviet Union, China, or North Korea.[5]

By the late 1970s, contacts between SWAPO and the South African Defence Force averaged one per day; over 900 clashes with nationalist guerrillas were being reported each year.[5]

Successful anti-colonial wars elsewhere also had a direct impact on events in South West Africa.[5] Victorious liberation movements in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Angola offered varying degrees of material support for SWAPO.

The new Angolan regime in particular proved an active benefactor, and permitted PLAN to operate from within their national boundaries.[13][14]

Deadlier escalation followed in 1978 when the SADF began crossing into Angola to strike at SWAPO positions; such actions were justified as necessary to prevent would-be ‘freedom fighters’ from infiltrating south into Ovamboland.[

60,000 South African soldiers were deployed to the operational area,[7] and defence costs spiraled upwards – eventually consuming a solid ten percent of Pretoria’s total expenditure.

PLAN responded by deploying increasingly sophisticated weaponry, including rockets, mortars, and an anti-aircraft arsenal of Soviet origin.[5][15]

In 1979, South African authorities began looking to recruit South West Africans for their war effort.

The addition of indigenous personnel, it was believed, would sow divisions among the territory’s populace, reduce SADF casualty rates, create the impression of a civil war rather than an anti-colonial struggle, and alleviate a growing manpower shortage.[16]

The creation of the South West African Territorial Force (SWATF) for local conscription was an excellent interim measure, but Defence Minister Magnus Malan also recognised the need for an intelligence-gathering unit similar to Rhodesia‘s Selous Scouts – a multiracial entity which had already demonstrated how small gangs of “pseudo terrorists”, trained to exceptionally high levels of subterfuge, could have an effect utterly disproportionate to their size.

Colonel Hans Dreyer, a former brigadier from the South African Police (SAP) division in Natal Province, was appointed to form the new unit accordingly. As a veteran of the Rhodesian Bush War.

Dreyer was more than familiar with the techniques employed by the Selous Scouts and applied hard lessons learned from that conflict.[18]

Since the passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 435 called for an end to South Africa’s military buildup but conceded that police units were necessary to maintain order during Namibia’s hypothetical elections and the proposed transition to independence.

Koevoet was designated a strictly police element.[16] Its initial members included sixty Ovambo trackers and ten white constables, many of whom had undergone prior training with the Special Task Force (Taakmag).

Even at its peak, Koevoet numbered no more than 3,000 field and support staff, including a core of senior officers recruited from South African law enforcement or the expiring Rhodesian Security Forces.

Angolan irregulars from the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) were also known to have served, along with former SWAPO supporters, known as “turned terrs”, bribed or coerced into joining.

Throughout its brief history the unit remained predominantly black and Oshiwambo speaking.[16] The SAP would not publicly acknowledge its existence until mid 1980, when a religious tabloid remarked on the use of a new special forces group linked to the assassination of known SWAPO sympathisers in Ovamboland.

The editorial named fifty persons on Colonel Dreyer’s alleged “death list”; although South Africa denied the report, officials did name Koevoet and praise it for its efficiency.[16]

| “ | The crowbar, which prises terrorists out of the bushveld like nails from rotten wood. | ” |

In court cases involving subsequent constables, the SAP disclosed that Koevoet had access to uniforms and arms similar to those furbished for SWAPO by the Soviet bloc, allowing members to actually impersonate guerrillas à la the Selous Scouts.

If civilians welcomed the imposters, they were interrogated.[18] Other patrols scoured known infiltration routes in mine-protected Casspir armoured personnel carriers, tirelessly tracking their quarries for weeks on end.[20]

According to the South West African authorities, in 1981 alone five hundred rebel operatives were killed or arrested by the paramilitary at the cost of only twelve men. By 1984, search and destroy combat operations had taken precedence over intelligence gathering.[21]

A large part of Koevoet’s later work included APC patrols into guerrilla-held areas. Sometimes mortar attacks were carried out on guerrilla camps, followed by armoured assaults.

If necessary, a number of the operators would later dismount and pursue the enemy with small arms. Skilled trackers drawn from the local population were also hired to hunt down fugitives sought by the police.

Clashes between SWAPO and Koevoet became increasingly costly and fierce; in 1989 official estimates suggested that over three thousand guerrilla fighters were being killed or captured each year by the one unit alone.

Their use of torture and assassination, however, proved to be their undoing; SWAPO compiled a list of atrocities committed by Koevoet which was promptly released to the international press.

Even the South African government finally bowed to pressure and tried several operators for murder. In 1985 heavily armed Koevoet squads indiscriminately opened fire on anti-apartheid protestors in Windhoek.[citation needed]

Koevoet was a +-1000-man force consisting of about 900 Ovambo and about 300 white officers and SAP non-commissioned officers (NCOs).

It was organized into 40 to 50-man platoons equipped largely with MRAPs called Casspirsand Wolf Turbos for conducting patrols, a Duiker fuel truck and a Blesbok supply vehicle (both variants of a Casspir). They rotated one week in the bush for one week at camp.

There were three Koevoet units based in Kaokoland, Kavango, and Ovambo with each unit over several platoons.

Koevoet’s internal structure was the brainchild of Hans Dreyer (later a Major-General in the SAP) to develop and exploit counter-insurgency intelligence.

The concept was originally modeled on the Portuguese Flechas and Rhodesia’s Selous Scouts.

By the mid-1980s, certain estimates put Koevoet’s size at over a thousand troops.[citation needed] The organization established its formal headquarters in the present day town of Oshakati, Namibia.

The white officers were either South West African or South-African police officers and, as often as not, untrained for what were effectively military operations.

Accordingly, these officers were usually sent for additional training with South African Special Forces Brigade in bushcraft, tracking and small arms handling and tactics.

The Ovambo and Bushman trackers were rated as Special Constables, who essentially underwent intensive basic infantry training although many were captured and “turned” SWAPO fighters that had already received training of a sort elsewhere.

From a Koevoet operator’s perspective, Special Constables were “Counter Insurgency” (COIN) (Afrikaans: Teen Insurgensie (TEIN)), while Koevoet operators were Koevoete (meaning plural of Koevoet) and had higher status than Special Constables.

The trackers of the unit in the early days were local Owambu and not Bushmen as often claimed, but operations were conducted with the bushman and junior recces “bat” units with success.

The Owambu, although accepting the skills of the bushmen, were in close competition and were in actual tracking and not just knowledgeable of the habits of the “tracked” equal.

Officers trained on the Galil as well as other weapons as well.

Koevoet operatives learned many of their later tactics during service in the Rhodesian Bush War. A number of the men were originally sent as part of a South African support unit which trained under the British South Africa Police (BSAP) paramilitary.

It was because of this past association with the BSAP (Known as the “Black Boots” for their distinctly black footwear) that Koevoet would subsequently be referred to commonly as the “Green Boots”.

Several members of the former organization were later offered positions in Koevoet following the end of Rhodesia’s white minority rule.

Koevoet operations used highly mobile units that tracked groups of SWAPO fighters who were on foot. Their tracks were picked up in various ways, but most often from:[citation needed]

Once a suspicious track was found, a vehicle would leap-frog ahead a few kilometres to check for the same tracks, and once found, the other vehicles would race up to join them.

Using this technique they could make quickly catch up with the guerrillas who were travelling on foot. The technique borrowed strongly from experience gained during the Rhodesian Bush War.

The trackers could provide accurate estimates on the distance to the enemy, the speed at which they were travelling and their states of mind.

They were able to do this by “reading” factors such as abandoned equipment, changes from walking to running speed, reduced attempts at anti-tracking or splintering into smaller groups taking different directions (“bomb shelling”).[23]

Once the trackers sensed that the SWAPO fighters were close, they would often call in close air support[24]and retreat to the safety of the Casspir armoured personnel carriers to face an enemy typically armed with RPG-7 rocket launchers, rifle grenades, AK-47s, SKS carbines, mines and RPK and PKM machine guns.

Koevoet members were financially rewarded through a bounty system, which paid them for kills, prisoners and equipment they captured.

This practice allowed many of the members to earn significantly more than their normal salary, and resulted in competition between units.[25]

It also resulted in a complaints being raised by the Red Cross about the disproportionately low number of prisoners taken, and accusations of summary executions of prisoners.[26]

Former SADF generals like Constand Viljoen and Jan Geldenhuys were very critical of Koevoet’s activities, considering them cruel and crude,[27] and undermining of the army’s “hearts and minds” campaign.[21]

SWAPO’s accusations that Koevoet had conducted intimidation of voters during registration for the election was taken up by the United Nations.

Consequently, in October 1989, Koevoet was disbanded so that SWAPO could not accuse South Africa of influencing the election.[28]

Its members were incorporated nationwide into the South West African Police(SWAPOL). A notable percentage of operators were also known to have taken up work with the South West Africa Territorial Force.

The Koevoet issue was one of the most difficult the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) had to face. Because the unit was formed after the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 435 of 1978 (calling for South Africa’s immediate withdrawal from Namibia), it was not mentioned in the eventual settlement proposal or related documents.

Once Koevoet’s role became clear, the UN Secretary-General took the position that it was a paramilitary unit and, as such, should be disbanded as soon as the settlement proposal took effect.

About 2,000 of its members had been absorbed into SWAPOL before the implementation date of 1 April 1989 but they reverted to their former role against the SWAPO insurgents in the “events” of early April 1989.

Although ostensibly re-incorporated into SWAPOL in mid-May, the ex-Koevoet personnel continued to operate as a counter-insurgency unit travelling around the north in armoured and heavily armed convoys.[29]

In June 1989, the UN Special Representative in Namibia and head of UNTAG, Martti Ahtisaari, told the Administrator-General (South African appointee Louis Pienaar) that this behaviour was inconsistent with the settlement proposal, which required the police to be lightly armed.

Some Koevoet operators later maintained that where the SWAPOL-COIN police forces were weakened in order to meet the demand set by the proposal document, SWAPO had not yet relinquished its position and capabilities as an armed insurgent force, thus necessitating their cautious defiance.

The vast majority of the ex-Koevoet personnel were quite unsuited for continued employment in Namibian law enforcement and, if the issue was not dealt with soon, Ahtisaari threatened to dismiss Pienaar.

Ahtisaari’s tough stance in respect of these continuing Koevoet operations made him a target of the South African Civil Cooperation Bureau.

According to a hearing in September 2000 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, two CCB operatives (Kobus le Roux and Ferdinand Barnard) were tasked to give the UNTAG leader a “good hiding”.

To carry out the assault, Barnard had planned to use the grip handle of a metal saw as a knuckleduster. In the event, Ahtisaari did not attend the meeting at the Keetmanshoop Hotel, where Le Roux and Barnard were lying in wait for him, and thus escaped injury.[30]

There ensued a difficult process of negotiation with the South African government which continued for several months.

The UN Secretary-General pressed for the removal of all ex-Koevoet elements from SWAPOL, with Ahtisaari bringing to Pienaar’s attention many allegations of misconduct by them. UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar visited Namibia in July 1989, following which the UN Security Council demanded that Koevoet formally disarm and the dismantle its command structure.

Under such pressure, the South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, announced on 28 September 1989 that some 1,200 ex-Koevoet members of SWAPOL would be demobilized the next day.

A further 400 such personnel were demobilized on 30 October – both events were supervised by UNTAG military monitors.[31]

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was highly critical of Koevoet’s practices.

In its final report, the Commission concluded that the unit was “responsible for the perpetration of gross human rights violations in South West Africa and Angola”, and that “these violations amounted to a systematic pattern of abuse which entailed deliberate planning by the leadership of the SAP”.[32]

It use to be that these were not too hard and find.

But sadly the days when one would buy a gun and the Shop owner would point to a trash can full of Mausers and say.

“Throw in another $50 and you can choose one out of the lot”

Sadly are long gone. Oh well, nothing last forever, But there is always tomorrow!

Grumpy

| C-130 Hercules | |

|---|---|

|

|

| USAF C-130E | |

| Role | Military transport aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Lockheed Martin |

| First flight | 23 August 1954 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Marine Corps Royal Air Force Royal Australian Air Force |

| Produced | 1954–present |

| Number built | Over 2,500 as of 2015[1] |

| Unit cost | |

| Variants | AC-130 Spectre/Spooky Lockheed DC-130 Lockheed EC-130 Lockheed HC-130 Lockheed Martin KC-130 Lockheed LC-130 Lockheed MC-130 Lockheed WC-130 Lockheed L-100 Hercules Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules |

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is a four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft designed and built originally by Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin). Capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings, the C-130 was originally designed as a troop, medevac, and cargo transport aircraft. The versatile airframe has found uses in a variety of other roles, including as a gunship (AC-130), for airborne assault, search and rescue, scientific research support, weather reconnaissance, aerial refueling, maritime patrol, and aerial firefighting. It is now the main tactical airlifter for many military forces worldwide. Over forty variants and versions of the Hercules, including a civilian one marketed as the Lockheed L-100, operate in more than 60 nations.

The C-130 entered service with the U.S. in the 1950s, followed by Australia and others. During its years of service, the Hercules family has participated in numerous military, civilian and humanitarian aidoperations. In 2007, the C-130 became the fifth aircraft—after the English Electric Canberra, B-52 Stratofortress, Tupolev Tu-95, and KC-135 Stratotanker—to mark 50 years of continuous service with its original primary customer, in this case, the United States Air Force.[citation needed] The C-130 Hercules is the longest continuously produced military aircraft at over 60 years, with the updated Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules currently being produced.[4]

[hide]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Korean War showed that World War II-era piston-engine transports—Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcars, Douglas C-47 Skytrains and Curtiss C-46 Commandos—were inadequate for modern warfare. Thus, on 2 February 1951, the United States Air Force issued a General Operating Requirement (GOR) for a new transport to Boeing, Douglas, Fairchild, Lockheed, Martin, Chase Aircraft, North American, Northrop, and Airlifts Inc. The new transport would have a capacity of 92 passengers, 72 combat troops or 64 paratroopers in a cargo compartment that was approximately 41 feet (12 m) long, 9 feet (2.7 m) high, and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide. Unlike transports derived from passenger airliners, it was to be designed from the ground-up as a combat transport with loading from a hinged loading ramp at the rear of the fuselage.

A key feature was the introduction of the Allison T56 turboprop powerplant, first developed specifically for the C-130. At the time, the turboprop was a new application of gas turbines, which offered greater range at propeller-driven speeds compared to pure turbojets, which were faster but consumed more fuel. They also produced much more power for their weight than piston engines.

The Hercules resembled a larger four-engine brother to the C-123 Provider with a similar wing and cargo ramp layout that evolved from the Chase XCG-20 Avitruc, which in turn, was first designed and flown as a cargo glider in 1947.[5] The Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter also had a rear ramp, which made it possible to drive vehicles onto the plane (also possible with forward ramp on a C-124). The ramp on the Hercules was also used to airdrop cargo, which included low-altitude extraction for Sheridan tanks and even dropping large improvised “daisy cutter” bombs.

The new Lockheed cargo plane design possessed a range of 1,100 nmi (1,270 mi; 2,040 km), takeoff capability from short and unprepared strips, and the ability to fly with one engine shut down. Fairchild, North American, Martin, and Northrop declined to participate. The remaining five companies tendered a total of ten designs: Lockheed two, Boeing one, Chase three, Douglas three, and Airlifts Inc. one. The contest was a close affair between the lighter of the two Lockheed (preliminary project designation L-206) proposals and a four-turboprop Douglas design.

The Lockheed design team was led by Willis Hawkins, starting with a 130-page proposal for the Lockheed L-206.[6] Hall Hibbard, Lockheed vice president and chief engineer, saw the proposal and directed it to Kelly Johnson, who did not care for the low-speed, unarmed aircraft, and remarked, “If you sign that letter, you will destroy the Lockheed Company.”[6] Both Hibbard and Johnson signed the proposal and the company won the contract for the now-designated Model 82 on 2 July 1951.[7]

The first flight of the YC-130 prototype was made on 23 August 1954 from the Lockheed plant in Burbank, California. The aircraft, serial number 53-3397, was the second prototype, but the first of the two to fly. The YC-130 was piloted by Stanley Beltz and Roy Wimmer on its 61-minute flight to Edwards Air Force Base; Jack Real and Dick Stanton served as flight engineers. Kelly Johnson flew chase in a Lockheed P2V Neptune.[8]

After the two prototypes were completed, production began in Marietta, Georgia, where over 2,300 C-130s have been built through 2009.[9]

The initial production model, the C-130A, was powered by Allison T56-A-9 turboprops with three-blade propellers and originally equipped with the blunt nose of the prototypes. Deliveries began in December 1956, continuing until the introduction of the C-130B model in 1959. Some A-models were equipped with skis and re-designated C-130D. As the C-130A became operational with Tactical Air Command (TAC), the C-130’s lack of range became apparent and additional fuel capacity was added in the form of external pylon-mounted tanks at the end of the wings.

A Michigan Air National Guard C-130E dispatches its flares during a low-level training mission

The C-130B model was developed to complement the A-models that had previously been delivered, and incorporated new features, particularly increased fuel capacity in the form of auxiliary tanks built into the center wing section and an AC electrical system. Four-bladed Hamilton Standard propellers replaced the Aeroproducts three-blade propellers that distinguished the earlier A-models. The C-130B had ailerons with boost increased from 2,050 psi (14.1 MPa) to 3,000 psi(21 MPa), as well as uprated engines and four-blade propellers that were standard until the J-model’s introduction.

An electronic reconnaissance variant of the C-130B was designated C-130B-II. A total of 13 aircraft were converted. The C-130B-II was distinguished by its false external wing fuel tanks, which were disguised signals intelligence (SIGINT) receiver antennas. These pods were slightly larger than the standard wing tanks found on other C-130Bs. Most aircraft featured a swept blade antenna on the upper fuselage, as well as extra wire antennas between the vertical fin and upper fuselage not found on other C-130s. Radio call numbers on the tail of these aircraft were regularly changed so as to confuse observers and disguise their true mission.

The extended-range C-130E model entered service in 1962 after it was developed as an interim long-range transport for the Military Air Transport Service. Essentially a B-model, the new designation was the result of the installation of 1,360 US gal (5,150 L) Sargent Fletcher external fuel tanks under each wing’s midsection and more powerful Allison T56-A-7A turboprops. The hydraulic boost pressure to the ailerons was reduced back to 2,050 psi (14.1 MPa) as a consequence of the external tanks’ weight in the middle of the wingspan. The E model also featured structural improvements, avionicsupgrades and a higher gross weight. Australia took delivery of 12 C130E Hercules during 1966–67 to supplement the 12 C-130A models already in service with the RAAF. Sweden and Spain fly the TP-84T version of the C-130E fitted for aerial refueling capability.

The KC-130 tankers, originally C-130F procured for the US Marine Corps (USMC) in 1958 (under the designation GV-1) are equipped with a removable 3,600 US gal (13,626 L) stainless steel fuel tank carried inside the cargo compartment. The two wing-mounted hose and drogue aerial refueling pods each transfer up to 300 US gal per minute (19 L per second) to two aircraft simultaneously, allowing for rapid cycle times of multiple-receiver aircraft formations, (a typical tanker formation of four aircraft in less than 30 minutes). The US Navy‘s C-130G has increased structural strength allowing higher gross weight operation.

Royal Australian Air Force C-130H, 2007

The C-130H model has updated Allison T56-A-15 turboprops, a redesigned outer wing, updated avionics and other minor improvements. Later H models had a new, fatigue-life-improved, center wing that was retrofitted to many earlier H-models. For structural reasons, some models are required to land with certain amounts of fuel when carrying heavy cargo, reducing usable range.[10] The H model remains in widespread use with the United States Air Force (USAF) and many foreign air forces. Initial deliveries began in 1964 (to the RNZAF), remaining in production until 1996. An improved C-130H was introduced in 1974, with Australia purchasing 12 of type in 1978 to replace the original 12 C-130A models, which had first entered RAAF Service in 1958. The U.S. Coast Guard employs the HC-130H for long-range search and rescue, drug interdiction, illegal migrant patrols, homeland security, and logistics.

United States Coast Guard HC-130H

C-130H models produced from 1992 to 1996 were designated as C-130H3 by the USAF. The “3” denoting the third variation in design for the H series. Improvements included ring laser gyros for the INUs, GPS receivers, a partial glass cockpit (ADI and HSI instruments), a more capable APN-241 color radar, night vision device compatible instrument lighting, and an integrated radar and missile warning system. The electrical system upgrade included Generator Control Units (GCU) and Bus Switching units (BSU) to provide stable power to the more sensitive upgraded components.[11]

Royal Air Force C-130K (C.3)

The equivalent model for export to the UK is the C-130K, known by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as the Hercules C.1. The C-130H-30 (Hercules C.3 in RAF service) is a stretched version of the original Hercules, achieved by inserting a 100 in (2.54 m) plug aft of the cockpit and an 80 in (2.03 m) plug at the rear of the fuselage. A single C-130K was purchased by the Met Office for use by its Meteorological Research Flight, where it was classified as the Hercules W.2. This aircraft was heavily modified (with its most prominent feature being the long red and white striped atmospheric probe on the nose and the move of the weather radar into a pod above the forward fuselage). This aircraft, named Snoopy, was withdrawn in 2001 and was then modified by Marshall of Cambridge Aerospaceas flight-testbed for the A400M turbine engine, the TP400. The C-130K is used by the RAF Falcons for parachute drops. Three C-130K (Hercules C Mk.1P) were upgraded and sold to the Austrian Air Force in 2002.[12]

The MC-130E Combat Talon was developed for the USAF during the Vietnam War to support special operations missions in Southeast Asia, and led to both the MC-130H Combat Talon II as well as a family of other special missions aircraft. 37 of the earliest models currently operating with the Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) are scheduled to be replaced by new-production MC-130J versions. The EC-130 Commando Solo is another special missions variant within AFSOC, albeit operated solely by an AFSOC-gained wing in the Pennsylvania Air National Guard, and is a psychological operations/information operations (PSYOP/IO) platform equipped as an aerial radio station and television stations able to transmit messaging over commercial frequencies. Other versions of the EC-130, most notably the EC-130H Compass Call, are also special variants, but are assigned to the Air Combat Command (ACC). The AC-130 gunship was first developed during the Vietnam War to provide close air support and other ground-attack duties.

USAF HC-130P refuels a HH-60G Pavehawk helicopter

The HC-130 is a family of long-range search and rescue variants used by the USAF and the U.S. Coast Guard. Equipped for deep deployment of Pararescuemen (PJs), survival equipment, and (in the case of USAF versions) aerial refueling of combat rescue helicopters, HC-130s are usually the on-scene command aircraft for combat SAR missions (USAF only) and non-combat SAR (USAF and USCG). Early USAF versions were also equipped with the Fulton surface-to-air recovery system, designed to pull a person off the ground using a wire strung from a helium balloon. The John Wayne movie The Green Beretsfeatures its use. The Fulton system was later removed when aerial refueling of helicopters proved safer and more versatile. The movie The Perfect Storm depicts a real life SAR mission involving aerial refueling of a New York Air National GuardHH-60G by a New York Air National Guard HC-130P.

The C-130R and C-130T are U.S. Navy and USMC models, both equipped with underwing external fuel tanks. The USN C-130T is similar, but has additional avionics improvements. In both models, aircraft are equipped with Allison T56-A-16 engines. The USMC versions are designated KC-130R or KC-130T when equipped with underwing refueling pods and pylons and are fully night vision system compatible.

The RC-130 is a reconnaissance version. A single example is used by the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force, the aircraft having originally been sold to the former Imperial Iranian Air Force.

The Lockheed L-100 (L-382) is a civilian variant, equivalent to a C-130E model without military equipment. The L-100 also has two stretched versions.

In the 1970s, Lockheed proposed a C-130 variant with turbofan engines rather than turboprops, but the U.S. Air Force preferred the takeoff performance of the existing aircraft. In the 1980s, the C-130 was intended to be replaced by the Advanced Medium STOL Transport project. The project was canceled and the C-130 has remained in production.

Building on lessons learned, Lockheed Martin modified a commercial variant of the C-130 into a High Technology Test Bed (HTTB). This test aircraft set numerous short takeoff and landing performance records and significantly expanded the database for future derivatives of the C-130.[13] Modifications made to the HTTB included extended chord ailerons, a long chord rudder, fast-acting double-slotted trailing edge flaps, a high-camber wing leading edge extension, a larger dorsal fin and dorsal fins, the addition of three spoiler panels to each wing upper surface, a long-stroke main and nose landing gear system, and changes to the flight controls and a change from direct mechanical linkages assisted by hydraulic boost, to fully powered controls, in which the mechanical linkages from the flight station controls operated only the hydraulic control valves of the appropriate boost unit.[14] The HTTB first flew on 19 June 1984, with civil registration of N130X. After demonstrating many new technologies, some of which were applied to the C-130J, the HTTB was lost in a fatal accident on 3 February 1993, at Dobbins Air Reserve Base, in Marietta, Georgia.[15] The crash was attributed to disengagement of the rudder fly-by-wire flight control system, resulting in a total loss of rudder control capability while conducting ground minimum control speed tests (Vmcg). The disengagement was a result of the inadequate design of the rudder’s integrated actuator package by its manufacturer; the operator’s insufficient system safety review failed to consider the consequences of the inadequate design to all operating regimes. A factor which contributed to the accident was the flight crew’s lack of engineering flight test training.[16]

In the 1990s, the improved C-130J Super Hercules was developed by Lockheed (later Lockheed Martin). This model is the newest version and the only model in production. Externally similar to the classic Hercules in general appearance, the J model has new turboprop engines, six-bladed propellers, digital avionics, and other new systems.[17]

In 2000, Boeing was awarded a US$1.4 billion contract to develop an Avionics Modernization Program kit for the C-130. The program was beset with delays and cost overruns until project restructuring in 2007.[18] On 2 September 2009, Bloomberg news reported that the planned Avionics Modernization Program (AMP) upgrade to the older C-130s would be dropped to provide more funds for the F-35, CV-22 and airborne tanker replacement programs.[19] However, in June 2010, Department of Defense approved funding for the initial production of the AMP upgrade kits.[20][21] Under the terms of this agreement, the USAF has cleared Boeing to begin low-rate initial production (LRIP) for the C-130 AMP. A total of 198 aircraft are expected to feature the AMP upgrade. The current cost per aircraft is US$14 million although Boeing expects that this price will drop to US$7 million for the 69th aircraft.[18]

In the 2000s, Lockheed Martin and the U.S. Air Force began outfitting and retrofitting C-130s with the eight-blade UTC Aerospace Systems NP2000 propellers.[22]

An engine enhancement program saving fuel and providing lower temperatures in the T56 engine has been approved, and the US Air Force expects to save $2 billion and extend the fleet life.[23]

In October 2010, the Air Force released a capabilities request for information (CRFI) for the development of a new airlifter to replace the C-130. The new aircraft is to carry a 190 percent greater payload and assume the mission of mounted vertical maneuver (MVM). The greater payload and mission would enable it to carry medium-weight armored vehicles and drop them off at locations without long runways. Various options are being considered, including new or upgraded fixed-wing designs, rotorcraft, tiltrotors, or even an airship. Development could start in 2014, and become operational by 2024. The C-130 fleet of around 450 planes would be replaced by only 250 aircraft.[24] The Air Force had attempted to replace the C-130 in the 1970s through the Advanced Medium STOL Transport project, which resulted in the C-17 Globemaster IIIthat instead replaced the C-141 Starlifter.[25] The Air Force Research Laboratory funded Lockheed and Boeing demonstrators for the Speed Agile concept, which had the goal of making a STOL aircraft that can take off and land at speeds as low as 70 kn (130 km/h; 81 mph) on airfields less than 2,000 ft (610 m) long and cruise at Mach 0.8-plus. Boeing’s design used upper-surface blowing from embedded engines on the inboard wing and blown flaps for circulation control on the outboard wing. Lockheed’s design also used blown flaps outboard, but inboard used patented reversing ejector nozzles. Boeing’s design completed over 2,000 hours of windtunnel tests in late 2009. It was a 5 percent-scale model of a narrowbody design with a 55,000 lb (25,000 kg) payload. When the AFRL increased the payload requirement to 65,000 lb (29,000 kg), they tested a 5% scale model of a widebody design with a 303,000 lb (137,000 kg) take-off gross weight and an “A400M-size” 158 in (4.0 m) wide cargo box. It would be powered by four IAE V2533 turbofans.[26] In August 2011, the AFRL released pictures of the Lockheed Speed Agile concept demonstrator. A 23% scale model went through wind tunnel tests to demonstrate its hybrid powered lift, which combines a low drag airframe with simple mechanical assembly to reduce weight and better aerodynamics. The model had four engines, including two Williams FJ44 turbofans.[25][27] On 26 March 2013, Boeing was granted a patent for its swept-wing powered lift aircraft.[28]

As of January 2014, Air Mobility Command, Air Force Materiel Command and the Air Force Research Lab are in the early stages of defining requirements for the C-X next generation airlifter program to replace both the C-130 and C-17. An aircraft would be produced from the early 2030s to the 2040s. If requirements are decided for operating in contested airspace, Air Force procurement of C-130s would end by the end of the decade to not have them serviceable by the 2030s and operated when they cannot perform in that environment. Development of the airlifter depends heavily on the Army’s “tactical and operational maneuver” plans. Two different cargo planes could still be created to separately perform tactical and strategic missions, but which course to pursue is to be decided before C-17s need to be retired.[29]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

USMC KC-130F Hercules performing takeoffs and landings aboard the aircraft carrier Forrestal in 1963. The aircraft is now displayed at the National Museum of Naval Aviation.

The first batch of C-130A production aircraft were delivered beginning in 1956 to the 463d Troop Carrier Wing at Ardmore AFB, Oklahoma and the 314th Troop Carrier Wing at Sewart AFB, Tennessee. Six additional squadrons were assigned to the 322d Air Divisionin Europe and the 315th Air Division in the Far East. Additional aircraft were modified for electronics intelligence work and assigned to Rhein-Main Air Base, Germany while modified RC-130As were assigned to the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) photo-mapping division.

In 1958, a U.S. reconnaissance C-130A-II of the 7406th Support Squadron was shot down over Armenia by four Soviet MiG-17s along the Turkish-Armenian border during a routine mission.[30]

Australia became the first non-American force to operate the C-130A Hercules with 12 examples being delivered from late 1958. The Royal Canadian Air Force became another early user with the delivery of four B-models (Canadian designation C-130 Mk I) in October / November 1960.[31]

In 1963, a Hercules achieved and still holds the record for the largest and heaviest aircraft to land on an aircraft carrier.[32] During October and November that year, a USMC KC-130F (BuNo 149798), loaned to the U.S. Naval Air Test Center, made 29 touch-and-go landings, 21 unarrested full-stop landings and 21 unassisted take-offs on Forrestal at a number of different weights.[33][34] The pilot, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) James H. Flatley III, USN, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in this test series. The tests were highly successful, but the idea was considered too risky for routine carrier onboard delivery (COD) operations. Instead, the Grumman C-2 Greyhoundwas developed as a dedicated COD aircraft. The Hercules used in the test, most recently in service with Marine Aerial Refueler Squadron 352 (VMGR-352) until 2005, is now part of the collection of the National Museum of Naval Aviation at NAS Pensacola, Florida.

In 1964, C-130 crews from the 6315th Operations Group at Naha Air Base, Okinawa commenced forward air control (FAC; “Flare”) missions over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos supporting USAF strike aircraft. In April 1965 the mission was expanded to North Vietnam where C-130 crews led formations of Martin B-57 Canberra bombers on night reconnaissance/strike missions against communist supply routes leading to South Vietnam. In early 1966 Project Blind Bat/Lamplighter was established at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. After the move to Ubon the mission became a four-engine FAC mission with the C-130 crew searching for targets then calling in strike aircraft. Another little-known C-130 mission flown by Naha-based crews was Operation Commando Scarf, which involved the delivery of chemicals onto sections of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos that were designed to produce mud and landslides in hopes of making the truck routes impassable.[citation needed]

In November 1964, on the other side of the globe, C-130Es from the 464th Troop Carrier Wing but loaned to 322d Air Division in France, took part in Operation Dragon Rouge, one of the most dramatic missions in history in the former Belgian Congo. After communist Simba rebels took white residents of the city of Stanleyville hostage, the U.S. and Belgium developed a joint rescue mission that used the C-130s to drop, air-land and air-lift a force of Belgian paratroopers to rescue the hostages. Two missions were flown, one over Stanleyville and another over Paulis during Thanksgiving weeks.[35] The headline-making mission resulted in the first award of the prestigious MacKay Trophy to C-130 crews.

In the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, as a desperate measure the transport No. 6 Squadron of the Pakistan Air Forcemodified its entire small fleet of C-130Bs for use as heavy bombers, capable of carrying up to 20,000 lb (9,072 kg) of bombs on pallets. These improvised bombers were used to hit Indian targets such as bridges, heavy artillery positions, tank formations and troop concentrations.[36][37] Some C-130s even flew with anti-aircraft guns fitted on their ramp, apparently shooting down some 17 aircraft and damaging 16 others.[38]

C-130 Hercules were used in the Battle of Kham Duc in 1968, when the North Vietnamese Army forced U.S.-led forces to abandon the Kham Duc Special Forces Camp.

In October 1968, a C-130Bs from the 463rd Tactical Airlift Wing dropped a pair of M-121 10,000 pound bombs that had been developed for the massive Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber but had never been used. The U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force resurrected the huge weapons as a means of clearing landing zones for helicopters and in early 1969 the 463rd commenced Commando Vault missions. Although the stated purpose of COMMANDO VAULT was to clear LZs, they were also used on enemy base camps and other targets.[citation needed]

During the late 1960s, the U.S. was eager to get information on Chinese nuclear capabilities. After the failure of the Black Cat Squadron to plant operating sensor pods near the Lop Nur Nuclear Weapons Test Base using a Lockheed U-2, the CIA developed a plan, named Heavy Tea, to deploy two battery-powered sensor pallets near the base. To deploy the pallets, a Black Bat Squadron crew was trained in the U.S. to fly the C-130 Hercules. The crew of 12, led by Col Sun Pei Zhen, took off from Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base in an unmarked U.S. Air Force C-130E on 17 May 1969. Flying for six and a half hours at low altitude in the dark, they arrived over the target and the sensor pallets were dropped by parachute near Anxi in Gansu province. After another six and a half hours of low altitude flight, they arrived back at Takhli. The sensors worked and uploaded data to a U.S. intelligence satellite for six months, before their batteries failed. The Chinese conducted two nuclear tests, on 22 September 1969 and 29 September 1969, during the operating life of the sensor pallets. Another mission to the area was planned as Operation Golden Whip, but was called off in 1970.[39] It is most likely that the aircraft used on this mission was either C-130E serial number 64-0506 or 64-0507 (cn 382-3990 and 382-3991). These two aircraft were delivered to Air America in 1964.[40] After being returned to the U.S. Air Force sometime between 1966 and 1970, they were assigned the serial numbers of C-130s that had been destroyed in accidents. 64-0506 is now flying as 62-1843, a C-130E that crashed in Vietnam on 20 December 1965 and 64-0507 is now flying as 63-7785, a C-130E that had crashed in Vietnam on 17 June 1966.[41]

The A-model continued in service through the Vietnam War, where the aircraft assigned to the four squadrons at Naha AB, Okinawa and one at Tachikawa Air Base, Japan performed yeoman’s service, including operating highly classified special operations missions such as the BLIND BAT FAC/Flare mission and FACT SHEET leaflet mission over Laos and North Vietnam. The A-model was also provided to the Republic of Vietnam Air Force as part of the Vietnamization program at the end of the war, and equipped three squadrons based at Tan Son Nhut AFB. The last operator in the world is the Honduran Air Force, which is still flying one of five A model Hercules (FAH 558, c/n 3042) as of October 2009.[42] As the Vietnam War wound down, the 463rd Troop Carrier/Tactical Airlift Wing B-models and A-models of the 374th Tactical Airlift Wing were transferred back to the United States where most were assigned to Air Force Reserve and Air National Guardunits.

U.S. Marines disembark from C-130 transports at Da Nang Air Base on 8 March 1965

Another prominent role for the B model was with the United States Marine Corps, where Hercules initially designated as GV-1s replaced C-119s. After Air Force C-130Ds proved the type’s usefulness in Antarctica, the U.S. Navy purchased a number of B-models equipped with skis that were designated as LC-130s. C-130B-II electronic reconnaissance aircraft were operated under the SUN VALLEY program name primarily from Yokota Air Base, Japan. All reverted to standard C-130B cargo aircraft after their replacement in the reconnaissance role by other aircraft.

The C-130 was also used in the 1976 Entebbe raid in which Israeli commandoforces carried a surprise assault to rescue 103 passengers of an airliner hijacked by Palestinian and German terrorists at Entebbe Airport, Uganda. The rescue force—200 soldiers, jeeps, and a black Mercedes-Benz (intended to resemble Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin‘s vehicle of state)—was flown over 2,200 nmi (4,074 km; 2,532 mi) almost entirely at an altitude of less than 100 ft (30 m) from Israel to Entebbe by four Israeli Air Force (IAF) Hercules aircraft without mid-air refueling (on the way back, the aircraft refueled in Nairobi, Kenya).

During the Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas) of 1982, Argentine Air Force C-130s undertook highly dangerous, daily re-supply night flights as blockade runners to the Argentine garrison on the Falkland Islands. They also performed daylight maritime survey flights. One was lost during the war, shot down by a Royal Navy Sea Harrier. Argentina also operated two KC-130 tankers during the war, and these refueled both the Douglas A-4 Skyhawks and Navy Dassault-Breguet Super Étendards; some C-130s were modified to operate as bombers with bomb-racks under their wings. The British also used RAF C-130s to support their logistical operations.

USMC C-130T Fat Albertperforming a rocket-assisted takeoff(RATO)

During the Gulf War of 1991 (Operation Desert Storm), the C-130 Hercules was used operationally by the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, along with the air forces of Australia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and the UK. The MC-130 Combat Talon variant also made the first attacks using the largest conventional bombs in the world, the BLU-82 “Daisy Cutter” and GBU-43/B “Massive Ordnance Air Blast” bomb, (MOAB). Daisy Cutters were used to clear landing zones and to eliminate mine fields. The weight and size of the weapons make it impossible or impractical to load them on conventional bombers. The GBU-43/B MOAB is a successor to the BLU-82 and can perform the same function, as well as perform strike functions against hardened targets in a low air threat environment.

Since 1992, two successive C-130 aircraft named Fat Albert have served as the support aircraft for the U.S. Navy Blue Angels flight demonstration team. Fat Albert I was a TC-130G (151891),[43] while Fat Albert II is a C-130T (164763).[44]Although Fat Albert supports a Navy squadron, it is operated by the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) and its crew consists solely of USMC personnel. At some air shows featuring the team, Fat Albert takes part, performing flyovers. Until 2009, it also demonstrated its rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO) capabilities; these ended due to dwindling supplies of rockets.[45]

The AC-130 also holds the record for the longest sustained flight by a C-130. From 22 to 24 October 1997, two AC-130U gunships flew 36 hours nonstop from Hurlburt Field Florida to Taegu (Daegu), South Korea while being refueled seven times by KC-135 tanker aircraft. This record flight shattered the previous record longest flight by over 10 hours while the two gunships took on 410,000 lb (190,000 kg) of fuel. The gunship has been used in every major U.S. combat operation since Vietnam, except for Operation El Dorado Canyon, the 1986 attack on Libya.[46]

During the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the ongoing support of the International Security Assistance Force (Operation Enduring Freedom), the C-130 Hercules has been used operationally by Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, the UK and the United States.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom), the C-130 Hercules was used operationally by Australia, the UK and the United States. After the initial invasion, C-130 operators as part of the Multinational force in Iraq used their C-130s to support their forces in Iraq.

Since 2004, the Pakistan Air Force has employed C-130s in the War in North-West Pakistan. Some variants had forward looking infrared (FLIR Systems Star Safire III EO/IR) sensor balls, to enable close tracking of Islamist militants.[47]

A C-130E fitted with a MAFFS-1 dropping fire retardant

The U.S. Forest Service developed the Modular Airborne FireFighting System for the C-130 in the 1970s, which allows regular aircraft to be temporarily converted to an airtanker for fighting wildfires.[48] In the late 1980s, 22 retired USAF C-130As were removed from storage at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and transferred to the U.S. Forest Service, which then illegally transferred them to six private companies to be converted into air tankers. After one of these aircraft crashed due to wing separation in flight as a result of fatigue stress cracking, the entire fleet of C-130A air tankers was permanently grounded in 2004. C-130s were used to spread chemical dispersants onto the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf Coast in 2010.[49]

A recent development of a C-130–based airtanker is the Retardant Aerial Delivery System developed by Coulson Aviation USA. The system consists of a C-130H/Q retrofitted with an in-floor discharge system, combined with a removable 3,500- or 4,000-gallon water tank. The combined system is FAA certified.[50]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

RAAF C-130J-30 at Point Cook, 2006

Brazilian Air Force C-130 (L-382)

Significant military variants of the C-130 include:

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

C-130H used by the Egyptian Air Force.

Japan Air Self-Defense Force C-130H

Japan Air Self-Defense Force C-130H above Mount Fuji

Bangladesh Air Force C-130B

Former operators

The C-130 Hercules has had a low accident rate in general. The Royal Air Force recorded an accident rate of about one aircraft loss per 250,000 flying hours over the last 40 years, placing it behind Vickers VC10s and Lockheed TriStars with no flying losses.[59] USAF C-130A/B/E-models had an overall attrition rate of 5% as of 1989 as compared to 1-2% for commercial airliners in the U.S., according to the NTSB, 10% for B-52 bombers, and 20% for fighters (F-4, F-111), trainers (T-37, T-38), and helicopters (H-3).[60]

A total of 70 aircraft were lost by the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Marine Corps during combat operations in the Vietnam War in Southeast Asia. By the nature of the Hercules’ worldwide service, the pattern of losses provides an interesting barometer of the global hot spots over the past 50 years.[61]

C-130 at the Royal Saudi Air Force Museum

Data from USAF C-130 Hercules fact sheet,[84] International Directory of Military Aircraft,[85] Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft,[86] Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft[87]

General characteristics

Performance

Avionics

Payback sure is a Bitch huh?