- House Bill 22, House Bill 106, House Bill 284, House Bill 324 & House Bill 662 requiring the REPORTING OF LAWFUL SALES of certain firearms and magazines to state and/or local law enforcement. [nope]

- House Bill 76 & Senate Bill 172 CRIMINALIZING the failure of a victim of gun theft to report having his or her firearms stolen. [unenforceable, according to the State Police]

- House Bill 88 & House Bill 447 further TAXING the sale of firearms and/or ammunition and firearms accessories. [higher taxes? in Texas? lol]

- House Bill 110, House Bill 146, House Bill 308 & Senate Bill 360 BANNING private firearms transfers at gun shows. [was that a unicorn I just saw?]

- House Bill 123, House Bill 136 & Senate Bill 144 so-called “red flag” GUN CONFISCATION legislation requiring firearms surrender without due process. [no due process… yeah, maybe they could get away with that in Illinois]

- House Bill 129, House Bill 565, House Bill 761, House Bill 781, House Bill 925, House Bill 996, House Bill 1072, Senate Bill 32 & Senate Bill 145 RAISING THE AGE for firearms sales, restricting firearms transfers to, or purchases by, young adults. [lowering the age would have more chance of passing]

- House Bill 155, House Bill 236, Senate Bill 170 & Senate Bill 370 BANNING private firearms transfers between certain family members and friends, requiring FFLs to process these transactions that would include federal paperwork for government approval at an undetermined fee. [yeah, we just love getting the feds’ noses stuck in our bidness in Texas]

- House Bill 817, House Bill 925 & Senate Bill 32 BANNING the manufacture, sale, purchase or possession of commonly-owned semi-automatic rifles, pistols and shotguns. [there aren’t enough body bags to enforce this little wet dream]

- House Bill 197 & House Bill 632 BANNING the sale or transfer and possession of standard capacity magazines that hold more than 10 rounds. [see the point above]

- House Bill 179, House Bill 216 & House Bill 244 RESTRICTING long gun open carry, with limited exceptions. [you mean, over and above the restrictions we already have, and that most Texans hate like poison and mostly ignore?]

- House Bill 298 establishes a 3-day WAITING PERIOD for firearms sales. [uh huh — I know we’ve got a lot of Californians come here recently, but we still ain’t California yet]

- House Bill 887 CRIMINALIZING the practice of home-building firearms. [sorry, I need to go get another hanky]

- House Bill 925 requiring enforcement of a whole host of newly-established firearms restrictions through PRIVATE CIVIL ACTIONS. [once again, this isn’t California or New fucking York]

- House Bill 1092 REPEALING Texas’ firearms industry non-discrimination act from the 2021 session. [considering the margin by which the latter was passed in 2021, that ain’t gonna happen either]

- Senate Bill 205 REPEALING Texas’ campus carry law. [because of all the dozens of mass shootings on Texas campuses over the past few years, maybe?]

- Senate Bill 253 STREAMLINING signage requirements for posting areas off-limits to gun owners, making it easier for property owners to ban carrying on-premises. [actually, that we have any such signs at all is something I and others intend to take up with our legislators]

Reach out & touch someone!

.jpg)

From the Taffin Dictionary of Sixgunning — “Perfect Packin’ Pistol is a title given to a sixgun or semi-automatic with a barrel not less than 4″, nor more than 5-1/2″, which can be carried easily all day in a well-designed holster, placed under a bed roll comfortably at night and can be expected to handle any situation which should arise.”

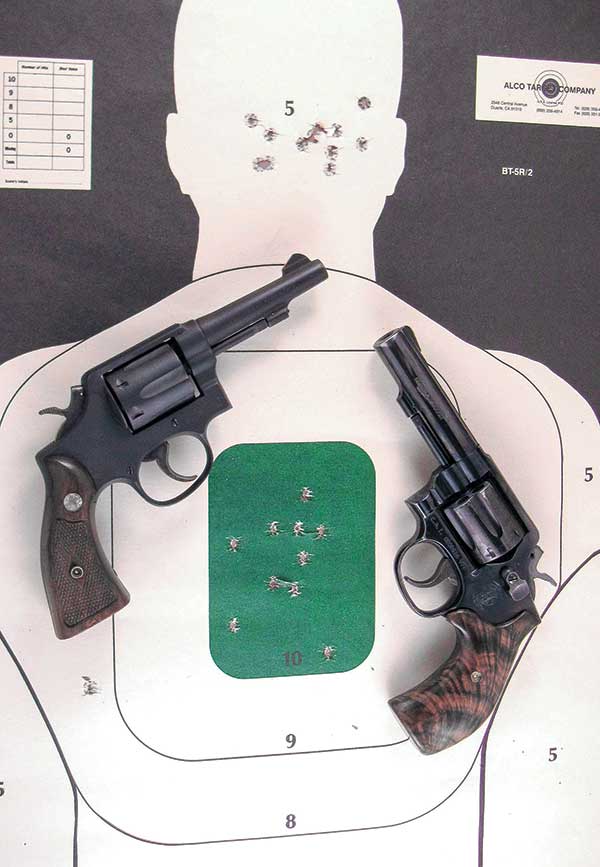

This definition takes in a lot of territory and obviously it depends where the bearer of such a PPP normally finds himself/herself. Whether daily travels take one on concrete, sagebrush, foothills, forests, or mountains, the encounters likely to occur have a great bearing on the caliber chosen have the duty. We will be taking a look at the epitome of Perfect Packin’ Pistols, namely the 4″ Double Action Smith & Wesson.

In The Beginning

To come up with the .38 Special, D.B. Wesson, along with his son, took a good look at the .38 Long Colt, the official U.S. Military Chambering at the time. The brass case was lengthened to accommodate 21-1/2 grains of black powder instead of the standard 18 and the bullet weight was increased from 150 grains to a round-nosed 158-grain bullet.

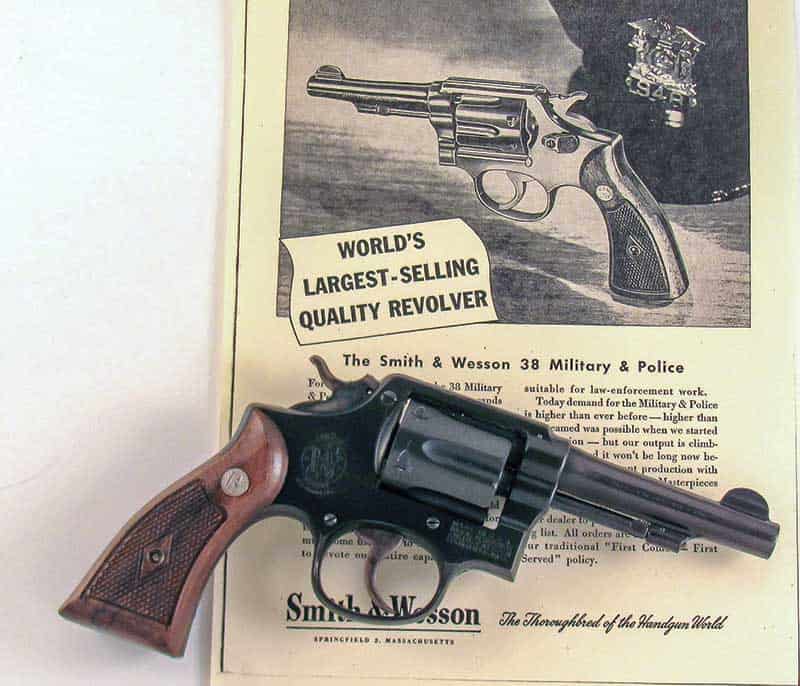

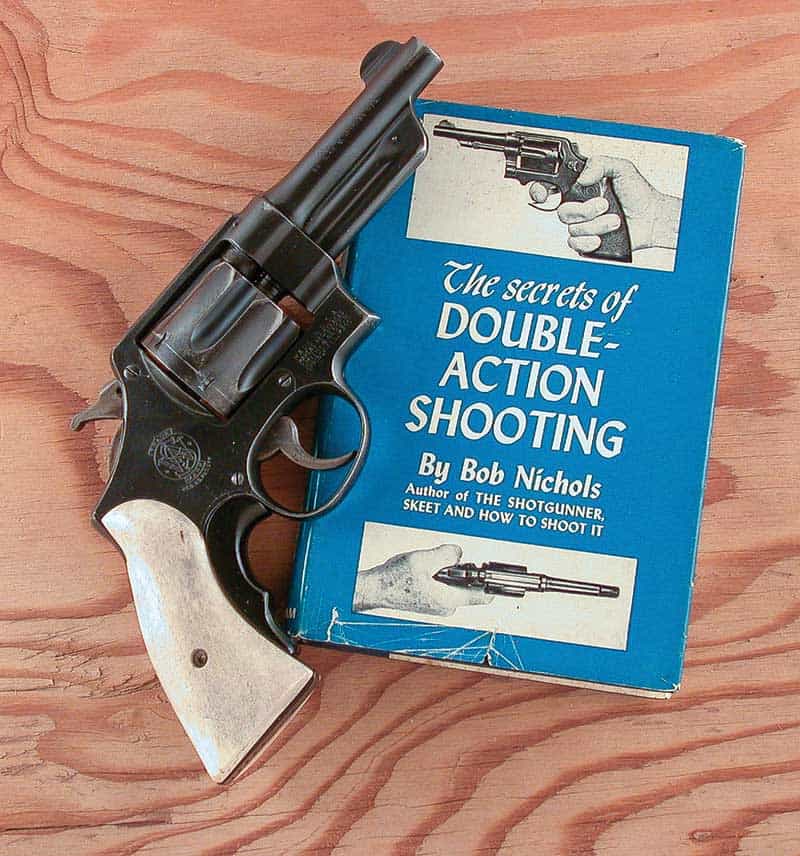

The new revolver was the first K-Frame and was given the name of Military & Police. For the next half-century plus, it would be found in the holsters of thousands upon thousands of police officers. Over the decades it would be made in the standard barrel configuration as well as a heavy barrel model in both blued and stainless finish. Bill Jordan especially liked the 4″ Heavy Barrel Military & Police in his exhibitions of fast double-action shooting.

With the coming of smokeless powder, the .38 Special was found to be especially accurate and from the very beginning the M&P was offered with target sights. Production of all civilian revolvers was shut down during WWII, however with the end of the war S&W began the development of what would become one of the finest target revolvers ever offered — the K-22.

A Masterpiece

The K-22 was introduced in December 1946 and six months later the first K-38, followed almost immediately by the K-32, arrived. These were all given the title of Masterpiece, which was definitely fitting. I have examples of all three revolvers chambered in .22 Long Rifle, .32 Smith & Wesson Long and .38 Special. They were and are excellent target pistols but too long to be classified as a PPP. This matter was handled in 1950 with the arrival of the 4″ Combat Masterpiece. This magnificent revolver was available in both .22 and .38 with a few examples and .32 Long.

In 1957 the .38 Special Combat Masterpiece became the Model 15 with the .22 Long Rifle version known as the Model 18. For situations where either one of these chamberings will suffice, it would be pretty difficult to find a better choice than the Combat Masterpiece.

The .38 Special, although a great choice for target shooting or plinking, left a lot to be desired in its original round-nosed 158-grain version. After WWI ended, our society was rapidly changing from an agrarian one and many of those who had been content to stay on the farm were now gravitating to the large cities; couple this with Prohibition and the easy money to be made outside the law — as well as the arrival of a new breed of criminal robbing banks escaping in a super-fast V8 powered sedan — and peace officers certainly found themselves behind the times.

The standard .38 Special that had served law officers for nearly 30 years suddenly had to compete with criminals firing .45s and automatic weapons from an automobile. Those little slow moving .38s either bounced off car bodies and windshields or at the very best, offered shallow penetration. Something had to be done to help officers. Smith & Wesson decided a newer and, more powerful, .38 Special was needed and the result was the .38/44 Heavy Duty.

Smith & Wesson, in conjunction with Winchester, in 1930 changed the standard .38 Special using a round-nosed bullet at around 850 fps to a flat-nosed semi-wadcutter design traveling 300 fps faster, and also added a metal-penetrating version. To house this new round, S&W simply used their 1926 Model, or 3rd Model Hand Ejector .44 Special with a .38 Special barrel and cylinder. The result was a much heavier sixgun than the S&W Military & Police and it did an excellent job of dampening recoil even with the new load.

The Military & Police has always been a relatively easy gun to shoot, however this new .38/44 had such a slick action and heavy cylinder it almost seemed to shoot by itself once the trigger action is started. From my perspective it is the finest .38 ever produced; and I am certainly not alone in this assessment. The following came from Elmer Keith.

“About a year ago Smith & Wesson heeded the demand for a heavier .38 with their new .38/44. This weapon was designed primarily as a police weapon and brought out on their .44 Military frame, to my notion the best sized and shaped frame of any double action for my individual hand.”

A New Start

The introduction of the .38/44 sixgun and cartridge did get the .38 Special up off its knees. However, this was only the beginning. The fixed-sighted .38/44 Heavy Duty was offered in barrel lengths of 4″, 5″ and 6-1/2″. In 1931 this latter model was upgraded with the addition of adjustable sights and introduced as the .38/44 Outdoorsman. Just as its name suggests, it became very popular as a field and hunting sixgun. A few were made with the 5″ length and I am certain there were those who shortened the barrel to an easy packing 4″. I had planned to do this someday, however someday has not yet arrived. My itch has been scratched with the use of .38 Special loads in the 4″ S&W Highway Patrolman.

In the early 1930s Col. Doug Wesson and writer/ballistician Phil Sharpe began working together on a new project using the .38/44. Sharpe had the .38 Special lengthened and their work together resulted in one of the finest sixgun/cartridge combinations, the .357 Registered Magnum and the .357 Magnum itself. Smith & Wesson Historian Roy Jinks called it the greatest sixgunning development of the 20th century. I will not argue with the assessment!

Both Model 57s shot very well, partly because they had great triggers.

The .41 Remington Magnum is in many ways the handgun equivalent of the .280 Remington and 16 gauge, a cartridge regarded by a relatively few True Believers as a perfect combination of ballistics and recoil. Like the .280 and 16, the .41 refuses to die, but all three rounds lag far behind the popularity of the dominant cartridges in their categories, the .44 Remington Magnum, .270 Winchester and 12 gauge.

While most 21st-century shooters remember Elmer Keith as the father of the .41 Magnum, other notable handgunners also had a part in its 1964 introduction, including Bill Jordan and Skeeter Skelton. The .41 was originally conceived as the perfect law enforcement round, more effective than the .38 Special and .357 Magnum then used by most American police departments, but more controllable than the .44 Magnum, considered the world’s most powerful handgun cartridge even nine years after its introduction in 1955.

The public’s fascination with the power of the .44 affected the success of the .41. Even the so-called “police” load produced by Remington, a 210-grain cast bullet at 1,050 feet per second, produced about twice the recoil of the typical .38 Special service load. The “hunting” load was a 210-grain bullet at 1,500 fps, developing over 1,000 foot-pounds of muzzle energy, and nearly the same recoil as the 240-grain “Hi-Speed” load of the .44 Magnum.

Too Big And Heavy

Also, Smith & Wesson chambered the .41 in the same large N-frame as the .44 Mag, calling it the Model 57. Instead of being somewhere between S&W’s smaller K-frame revolvers chambered for the .38 Special and .357 Mag and the .44 Model 29, the Model 57 weighed slightly more than the Model 29, due to the smaller hole in the barrel, so didn’t have any advantage as a carry revolver.

One of the oldest rules of breechloading firearms is there’s only so much space in any given cartridge category, and sales of the .41 lagged far behind the .44. Like devotees of the .280 and 16, the .41’s True Believers keep pointing out why this shouldn’t be so, citing small advantages in ballistics, including saying it shot flatter than the .44, a claim that originated with Elmer Keith.

Keith took a Model 57 along on a polar bear hunt, and he and his guide used the .41 to collect meat caribou. His published story pointed out the flatter trajectory of the .41. But if we run the numbers of 1964’s full-power 210-grain .41 and 240-grain .44 factory loads through Sierra’s Infinity ballistics program, using a zero range of 50 yards, we find the .41 only .3″ flatter at 150 yards—a long distance to be shooting at any big game animal with an iron-sighted revolver. With today’s factory loads the .44 shoots flatter, given equal bullet weights, even beyond 150 yards.

Please don’t take this wrong. My first handgun larger than a .357 Mag was a S&W Model 657, the stainless version of the 57, with a 6-1/2″ barrel. It was purchased new in 1989 as an all-around handgun for hunting big game, plus carrying as an emergency sidearm in Montana’s backcountry. The 657 shot very accurately, with a couple of loads grouping five rounds into around 2″ at 50 yards, not 25, partly because the trigger broke incredibly cleanly at around 3 pounds. Eventually I ended up owning two other .41s, a Ruger Blackhawk with 7-1/2″ barrel, and Thompson/Center Contender with a 10″ barrel. Both shot very well too.

New Competition

The 657 served its intended purposes over a decade or so, but eventually I grew weary of carrying 3 pounds of steel even when riding a horse. It also didn’t seem to kick a heck of a lot less than my friends’ .44 Magnums. Expanding handgun bullets had also improved enormously, making the .357 Mag a more definite self-defense round, and a number of single-action shooters had started heating up the old .45 Colt in new revolvers, with modern brass and heavier bullets. The .41 was not only competing with the .44 Magnum but the .45 Colt.

With .44 Magnum and .45 Colt components available in any Montana sporting goods store, I’d also grown weary of trying to find .41 Magnum brass and jacketed bullets. After accumulating a diverse collection of other revolvers, including a Taurus .44 Magnum with a 3″ barrel and a Ruger Blackhawk .45 Colt with a 7-1/2″ barrel, I sold my .41s and their reloading stuff.

Not too long thereafter, of course, the editor of GUNS asked for a handloading column on the .41. After putting an ad for a used .41 in the classified section of the popular Internet chat-room .24hourcampfire.com, but apparently the True Believers had driven up the price of .41s over the past few years.

Luckily, a couple of Montana friends, Kirk Stovall and Billy Stuver, saw the ad and offered to loan me their .41s and some fired brass. Both guns were S&W 57s, Kirk’s nickel-plated with an 8-3/8″ barrel, Billy’s a blued 4″ model. Both had the same great trigger pull as my departed 657, testing right around 3 pounds on a Timney trigger scale. Kirk offered the use of his RCBS dies, and Billy also provided some cast 230-grain bullets. Jacketed bullets were accumulated from several companies, and another 24hourcampfire guy, Ed Musetti, sent some BRP 270-grain cast bullets.

After a search through current data, nine loads were selected for testing. The original plan was to stick with newer powders, but H110/W296 turned up so often in the search it had to be retried. (They’re the same powder in different canisters.)

The first 25-yard group with Kirk’s nickel-plated .41, 16.0 grains of Accurate No. 9 and the 210-grain Nosler jacketed hollowpoint, was very reminiscent of my 657. Five shots went into barely over an inch! Not all the bullet/powder combinations shot as well, of course, but overall both revolvers shot very accurately.

Most .41 Magnums do shoot extremely well. One theory is that since .41s aren’t cranked out like .44 Magnums, the chambers, throats and overall alignment tend to vary less. The .41 also recoils slightly less than the .44 Magnum or a hot-loaded .45 Colt, while still providing sufficient power for most revolver tasks. By the end of the tests I was starting to believe again!

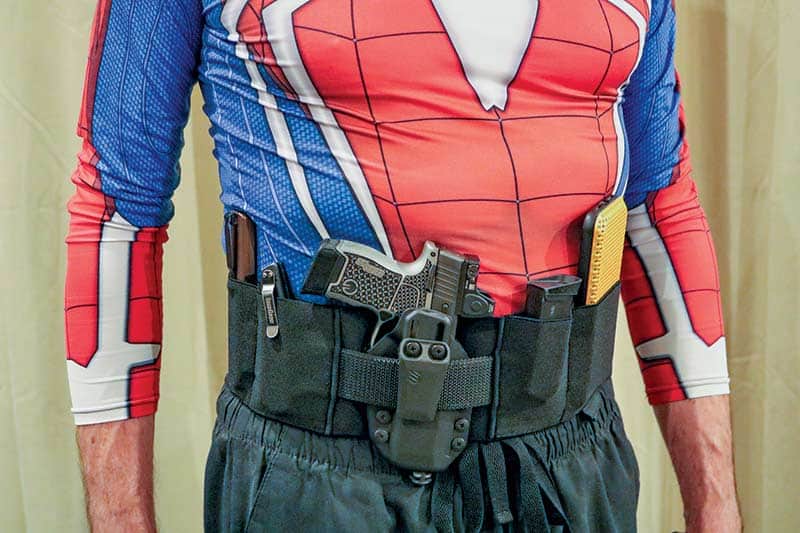

Note how all this rides above the belt. Any shirt will conceal it all.

If you found yourself in the suck, what sort of defensive weapon would you like to have handy? I’m thinking maybe an HK 416 or perhaps an M249 Para SAW with a truckload of ammo. While we’re dreaming, let’s make it a platoon of M1A2 SEP Abrams tanks and Close Air Support stacked up to the International Space Station. However, none of that stuff is terribly practical. It’s tough to conceal an M1 tank underneath a pair of shorts and a T-shirt while out with your best girl on a date.

Reality is that the best defensive firearm is the one you actually have on you. I’d much sooner have a Ruger 22/45 in my hand than that HK416 locked up in a gun box someplace. That’s why figuring out how you’re going to carry your gun is at least as important as the details of the gun itself.

I work in a busy medical clinic, so my daily uniform is basically pajamas. While that’s not THE reason I do what I do, that is indeed A reason I do what I do. Surgical scrubs are the next best thing to being naked, but they’re not necessarily the most efficient foundation for concealed carry.

I’ve tried quite literally everything. Pocket carry, ankle holsters, appendix carry and IWB rigs on a good stiff belt — all have their strengths and weaknesses. The rub is if something is uncomfortable or inefficient, you just won’t use it. The road to Hades is paved with fancy holsters that looked good on the website but rode like a wad of barbed wire stuffed down your Speedos. The Blackhawk Stache N.A.C.H.O. is legitimately different.

Tactical Details

N.A.C.H.O. stands for Non-Conventional Adaptive Carry Holster Option. That acronym seems a wee bit contrived, but the rig it describes is indisputably elegant. The Stache N.A.C.H.O. is a belly band. It comes in five different sizes to suit most any particular body habitus.

The N.A.C.H.O. is formed from wide, heavy-duty, double-ply 4″ elastic. A generous 3D mesh backer cushions the load and helps the rig breathe in hot climes. The edges are intentionally rounded to prevent chafing. Two integral 3″ pockets accommodate spare magazines or a flashlight. Another pair of 3.5″ pockets will carry your wallet and cell phone. No kidding, it’s like the Bat Belt. Just slap this rascal on, and you’re carrying all the sundry gear you might need to stay connected, supported, and safe while you’re out where the Wild Things roam.

The Stache N.A.C.H.O. includes a length of rigid 1.5″ double-layer scuba webbing to accept your favorite IWB holster. The system is really designed for weapons like the GLOCK 19 or smaller. The adaptive bit means the rig can be configured for appendix, hip, behind-the-hip, or mid-torso carry. I used mine with my SIG SAUER P365XL micro-carry gun.

Practical Tactical

In case you hadn’t noticed, people these days don’t dress quite like they did back when we were kids. The Stache N.A.C.H.O. is perfect for those times you’re not wearing jeans, 5.11s, or anything that doesn’t lend itself to a proper belt. Sweat pants, yoga pants, shorts and a T-shirt, skirts, dresses, kilts, or most any other sort of truly comfortable attire nicely complement the Stache N.A.C.H.O. This thing is just perfect underneath a pair of untucked surgical scrubs.

For starters, the Stache N.A.C.H.O. really is comfortable. The wide 4″ elastic spreads the weight of your gear out so it doesn’t eat into your anatomy. Pressure always equals force divided by surface area. That’s not just a good idea; that’s the law.

Your weapon is as positively retained as the holster you choose. You can customize your rig to your particular proclivities and circumstances. The Blackhawk Stache IWB base holster is a seamless fit. Even tricked out with my P365XL, smartphone, flashlight, knife and spare magazine, the whole rig still feels more comfortable than my old belt packing just the gun.

My draw was just as fast as with my previous conventional rig. I tried the orientation behind-the-hip, which is my custom, and in the front, both over my appendix as well as covering my belly button. If you can imagine it, the Stache N.A.C.H.O. will put your gun there. I found it fit best riding a bit higher than a typical belt. This changes the draw somewhat, but that’s the reason we train.

So, if you feel less is better when it comes to clothing and the only thing standing between you and that killer loincloth are those antiquated indecent exposure laws, then this is your minimalist concealed carry solution.