Jeanne Assam had a gut feeling that something terrible was about to happen as she watched parishioners leave a Sunday worship service at a Colorado megachurch one snow-covered December day.

That morning, a gunman had escaped after killing two people at a missionary training center about 70 miles away. Assam had a premonition that the gunman would next target the Colorado Springs church where she volunteered as an unpaid security officer. Her feeling was so strong that she volunteered to work that day, even though she had planned to stay home.

At 12:55 pm., Assam heard someone in the church lobby say that something weird was going on in the parking lot. Someone had lit a smoke bomb. A rifle shot then rang out in the parking lot. Assam heard a panicky voice shout from the packed crowd in the church lobby, “Get down! He’s got a gun!”

“I could tell it was the crack of a high-powered rifle,” Assam said. “It [the gunfire] was just thundering out really loud, just booming. People were screaming and running.”

As people fled, Assam reached for a Beretta 92FS 9mm semi-automatic pistol tucked in her jeans and sprinted toward the gunshots. She found a hiding spot near the church church’s main hallway.

She peeked out from her hiding spot and spotted the source of the rifle shots. A man was carrying an assault rifle in his left hand and had a thick black glove on his right hand. He was wearing a bulletproof vest and a backpack, and was cursing aloud as he moved, firing his rifle.

Assam gripped her Beretta and said a silent prayer: “God be with me.”

She then stepped from her hiding spot and faced the gunman.

What happened next at the New Life Church in December 2007 would change the way many churches approached security. It would also foreshadow a disturbing trend that has only worsened in subsequent years: 11 o’clock on Sunday morning is now one of the most dangerous hours of the week in America, pastors and church security officials say.

And for religious leaders, this poses a dilemma.

The church has become a frontline for the nation’s social ills

The New Life shooting was a transformative event that convinced many churches to add armed security to their Sunday morning worship services. But the security issues facing houses of worship have worsened since then, religious leaders and security officials say.

Church leaders say they are concerned about another array of threats that have become more common in a post-pandemic America where many people are on edge. Many of the contemporary issues afflicting the country — too many people carrying concealed weapons, domestic disputes that turn violent, people struggling with mental illnesses — are now spilling into Sunday morning worship services, pastors and security officials say.

Churches have long been concerned about losing members as church attendance plummets across denominations. Now they have a new worry: protecting those members that remain.

“Everything that is happening in the culture spills over into the church,” says the Rev. Brady Boyd, senior pastor of New Life Church, the same church where Assam confronted a gunman 16 years ago. Boyd says it’s rare but not uncommon for uniformed officers to handcuff someone creating a disturbance – usually related to a domestic dispute – in his church.

“That’s actually why the church exists,” he says. “The church should be a place where we see cultural problems manifest. It shouldn’t surprise us that we’re seeing broken families show up in our building, we’re seeing mental health issues and people wrestling with post-Covid anxiety.”

A house of worship, though, is traditionally the last place someone would expect to see lethal violence. Churches are called sanctuaries for a reason. A sanctuary is defined as a place of refuge and safety “set apart from the profane, ordinary world.”

But church and security officials say houses of worship are placed in a uniquely dangerous position every Sunday morning. Congregations are traditionally unprotected and are expected to welcome “the stranger” no matter how dangerous they may look. Houses of faith are one of the few public communal spaces in the country that were created to embrace all comers, including broken or disturbed people on the fringes of society.

The New Life shooting in Colorado ushered in an era of mass shootings where even churches are no longer safe.

In 2015, a White supremacist gunman killed nine worshippers at a historic Black church in Charleston, South Carolina. Two years later, a gunman killed 26 worshippers at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas. In 2019, a gunman killed two people inside a Texas Church of Christ—including an armed parishioner working security—before he was shot to death by another member of the church’s security team. The entire shooting incident, from the time the gunman pulled a weapon to the time he was shot, lasted six seconds.

And in May 2022 a gunman killed one person and wounded five others at a Presbyterian church in Orange County, California.

And then there are the less lethal acts of violence that don’t make the news. Those are hard to quantify, but a church security firm released a report in 2019 that estimated some 480 incidents of serious violence take place at communities of worship in the US each year. The report also said that two-thirds of the assailants had no affiliation with the congregation.

Mosques and synagogues have become targets too

These mass shootings, though, are not confined to churches. Every house of worship is now considered a soft target. In 2012 a man gunned down six people at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin. And in 2018, a gunman killed 11 worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. A 50-year-old man faces federal hate crime charges and the death penalty at his trial, which began in Pittsburgh last week.

Rabbi Hillel Norry of the Temple Beth David in Georgia says synagogues have recently started using more advanced protective technology, such as security apps and surveillance cameras with remote live feeds.

Most houses of worship are trying to find the balance between being too open or too vigilant, Norry says.

“There’s two things that I know are wrong: being wide open and the other is being closed up and shuttered where everything is locked up and only members can get in if they have the code,” says Norry, a black belt in Tae Kwon Do who advocates for armed self-defense in synagogues where it’s permitted.

“That’s why congregations are there – to greet people who we don’t know yet,” Norry says. “If not, close your doors and get into another line of work. If you’re only there for the people who are already there, that’s not church. That’s a club.”

Mosques also face increased fears about security. A gunman who killed 51 people during an attack on two mosques in New Zealand in 2019 demonstrated the potential risks of anti-Muslim sentiment in the US.

The CEO of a company that offers security training says mosques are struggling to pay for added security while now contending with a new threat.

“One of the biggest challenges facing mosques are cyberattacks,” says Shaukat Warraich of Mosque Security. “Aggressive and hateful emails and social media posts against [Islamic] centers have become more and more abusive.”

‘Hope is not a strategy,’ one security consultant says

These threats have led more churches to not only add and train armed security but to hire security consultants like Full Armor Church. Full Armor, like similar businesses, helps churches organize, train and operate security ministries. Dwayne Harris, Full Armor’s president, says the typical house of worship has about five minutes before a first responder answers an emergency, such as an active shooter, a member suffering a medical emergency or a fire.

Some churches’ security plans amount to this: Hope nothing bad happens, he says. Harris says he launched Full Armor in 2016 to accommodate a growing number of churches searching for ways to boost their security.

“Hope is not a strategy,” says Harris, an ordained bishop who says on his website that he “actively serves in full time law enforcement” and has experience with SWAT teams, and de-escalation training programs.

“You have to have some training, walk through and talk-through plans on how you’re going to confront a crisis,” Harris says.

Full Armor and other church security firms offer similar advice: Install video surveillance, train armed security staff, create a single entrance for the church and identify members with military, law enforcement and medical training.

One of the most effective weapons a church can deploy to protect itself is something else: friendliness, Harris says.

The more people can greet visitors to the church the more chance they can access potential risks. He cites the multiple checkpoints, or “touchpoints” that greet airline travelers. Each layer of interaction boosts security.

“Hospitality is the number one tool for church safety,” Harris says. “The more touchpoints you have for individuals, the easier it is to identify risks. Having touchpoints—greeting people at the door, interacting with them, and discovering their needs, their family dynamics—you may be able to identify someone who is agitated or has a grievance.”

Some of the biggest threats are internal

Despite the specter of mass shootings, some pastors say their greatest security challenges are internal. They cite other risks, such as mentally unstable members of the congregation or pedophiles who try to join church ministries that put them into contact with children.

Others also cited the threats of domestic violence or family disputes erupting in a congregation. An enraged man whose wife and children left him often knows where they will be on a Sunday morning.

“What causes some people to go south is they lost hope,” says the Rev. Tim Russell of the Light House Church in Missouri, which has an armed security staff.

“A man may have received a phone call. Their wife said, ‘I’m leaving after 30 years,’ and they lost their job. And they think they have nothing to live for, so they just go south.”

Sometimes a pastor’s sermon also can go south if they anger the wrong person. Pastors said they are seeing more people rushing the pulpit during services out of anger or a misguided attempt to share a message with the pastor.

Boyd, of New Life church, says he was preaching a holiday sermon two years ago about the violence in the Christmas story (Israel’s ruler ordered the execution of infants after hearing about Jesus’ impending birth) when a large young man rushed the pulpit, and started yelling and cursing at him.

At first, Boyd’s security team did nothing. They thought the pulpit intruder was a dramatic prop Boyd had arranged beforehand to deploy during his sermon.

Then they rushed the stage and subdued the man.

Boyd says the emotional demands on church leaders is almost nonstop.

“We have more counseling appointments for anxiety, fear, depression suicide than ever before in the history of our church right now,” he says.

Another concern, some pastors say, is the rise of churchgoers bringing concealed weapons into the pews. Many churches in the Bible Belt are located in open-carry states where worshippers often carry guns into services, pastors say.

Boyd says New Life typically has about 20 armed security officers in its sprawling church complex, which draws an estimated 14,000 members. But his church security does not have a monopoly on Sunday morning firepower. Colorado Springs is home to both an army and air force base. Many military veterans, aware of the church’s prior mass shooting, come to the service armed and ready, he says.

“Because we live in Colorado, where the gun laws are pretty liberal—if you can make fog on a mirror here you can get a gun—I bet we have 200 or 300 other people in our services that are carrying, men and women,” Boyd says.

He adds that having more guns in church does not make him feel safer.

“We would prefer people leave their weapons in their vehicle,” he says. “If a shooting were to happen and everyone pulled their weapons, it would be difficult to determine the good guys vs. the bad guys.”

Can churches go too far with security?

Adding too much security, though, could detract from the historic mission of houses of worship, some religious leaders and security officials say.

Churches are supposed to welcome the stranger, not frisk them, they say.

Churches are directed to minister to the “least of these” on the fringes of society. In many cases, the least of these include people who not dressed well, may be off the streets, may not smell well or act in unusual ways. If churches get too preoccupied with security, they could turn away the very people Jesus gravitated to, says the Rev. Tommy Mason of the Marion County Baptist Association in Alabama.

“You don’t want to turn people away just because they look a little different or because they don’t have the best clothes on,” says Mason, who received training from Full Armor to beef up his church’s security.

“And you don’t to be a place that looks like a prison or where you have a bunch of bouncers standing at the door. You have to welcome and assist them because they’re broken, and they want to hear the Word of God.”

How Assam stopped a gunman

Some broken people, though, may not want help. They may want to inflict pain.

That was the situation Assam, the New Life church volunteer, faced on that bitterly cold Sunday morning when she confronted a gunman in the megachurch”s main hallway.

“Police officer! Drop your weapon!” she shouted at the man as she leveled her Beretta handgun at him.

The man turned to her and leveled his weapon. He said nothing to her, Assam says. She fired.

“He just goes flying backwards, like had been pushed,” Assam says.

The gunman was down but still dangerous. He sat up and start firing at her again as she closed the distance, Assam says. She fired again, hitting him in his carotid artery. His blood splattered on her face, jeans and boots, Assam says.

By this time, the gunman had killed two teenaged sisters and wounded three others.

“It was awful to have to kill somebody,” Assam says. “I had to. He gave me no choice.”

Assam was widely lauded for her actions. President George W. Bush posed for pictures with her. News reports focused on her calm and faith. Assam credits her poise to her experience as a police officer. Before moving to Colorado Springs, she spent five years as an officer with the Minneapolis Police Department.

Assam says she supports churches elevating their security but that hiring armed staff with no experience in law enforcement or the military may not be enough. A shooting range doesn’t replicate the actual experience of facing a yelling, cursing human being charging at you with a weapon, she says.

“You’re going to be shooting at a human being who is probably enraged and not in the right mindset, and you cannot hesitate, or you will die.”

And yet armed church security cannot be too eager to use violence, she says.

“Not everybody who dresses weird is going to be an active shooter,” she says. “They need to be vigilant, but they also need to be compassionate and respectful of people who don’t look or smell like they do. Churches are like hospitals for the hurting.”

Houses of worship must strike a balance between openness and safety

Church leaders want their congregations to feel safe.

But striking a balance between protecting their flock and serving the broken stranger will be one of the most difficult challenges they face in the years ahead.

If they get the balance wrong, they can unintentionally accelerate the already alarming decline in church membership. And what may seem like vigilance could seem instead like hypocrisy.

Consider this sobering Sunday morning scenario:

A spiritual seeker visits a church and finds it filled with metal detectors and armed security guards carrying walkie-talkies. As he or she looks around, they may ask themselves, how can a church sing “A mighty fortress is our God” when they have security teams flanking the pastor and people deemed suspicious being ejected from the service?

This is the tension many places of worship must navigate today as they mobilize to protect their flock from spiritual and lethal threats.

They must somehow find a way to be both a sanctuary, and — when need be — a fortress.

India’s Fight Against China is a Nightmare

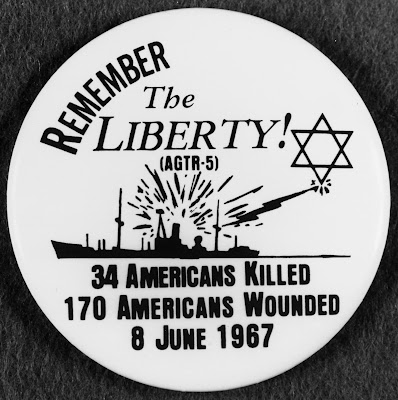

The USS Liberty

A Fifty-Year Wound

HRNM Docent & Contributing Writer

|

| William L.McGonagle (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph) |

On June 11, 1968, in Leutze Park at the Washington Navy Yard, Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius and Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, chief of naval operations, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor to Captain William L. McGonagle, commanding officer of USS Liberty (AGTR 5), for performance above and beyond the call of duty on June 8, 1967, when that ill-fated ship was attacked without warning by air and surface craft of the Israel Defense Forces.(1) The travail of that ship and her crew resulted from actions that have never, in the view of many of those who were on board, been truthfully explained by the attackers. However, the medal and many others earned as the result of that confrontation on the high seas are talismans of brave and selfless acts by a host of officers and enlisted personnel of the U.S. Navy.

The Humble Origins of a Spy Ship

|

| SS Simmons Victory in New York, 1947. (World Ship Society via navsource.org) |

Liberty began her life as SS Simmons Victory, a Victory-class cargo ship built during the Second World War by the Oregon Shipbuilding Company of Portland, Oregon and named for Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts. Completed about two months after being laid down, she was delivered to the War Shipping Administration on May 4th, 1945, and performed strategic lift operations under charter to the Pacific Far East Line, to include delivering ammunition from Port Chicago, California to Leyte for the impending invasion of Japan. Japan’s surrender in August obviated the necessity for this operation, and she returned the ammunition to Port Chicago. During the Korean War, she carried out similar duties. Simmons Victory was withdrawn from service in 1958 and placed in the National Defense Reserve Fleet in Olympia, Washington.

Acquired by the Navy in February 1963, Simmons Valley was converted to a “miscellaneous auxiliary ship,” and commissioned as USS Liberty on December 30, 1964, at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. She steamed to Norfolk in early 1965 for installation of equipment that would enable her crew to conduct communications surveillance and processing operations for the National Security Agency. Liberty was assigned to Service Squadron Eight, and following shakedown at Naval Base Guantanamo Bay began deployment to the west coast of Africa to participate in the Navy’s program of research and development in communications.

Liberty’s operations, and those of other technical research ships such as USS Banner (AGER 1), USS Pueblo (AGER 2), and USS Palm Beach (AGER 3), have retained a somewhat murky, mysterious character, though the role of the National Security Agency as an eavesdropping organization has more recently become publically known. The ships chosen for these missions were older, nondescript cargo vessels of uncertain pedigree that could be easily converted and equipped with costly electronic communications surveillance equipment. Publicly available information shows that, prior to her fateful voyage to the vicinity of the Sinai Peninsula, Liberty made three deployments to the West Coast of Africa between the Canary Islands and the Cape of Good Hope as “a floating research and development ship.”(2)

Into Harm’s Way

Liberty’s third deployment was interrupted by orders received during the morning watch on May 24th, 1967 at Abidjan, Ivory Coast, where the ship’s crew was enjoying a liberty port. The ship was ordered to proceed over 3,000 miles at best speed to Rota, Spain. There, she was to take on additional personnel and equipment for sensitive assignments in connection with worsening tensions between the United Arab Republic (present-day Egypt) and the State of Israel. Following an eight-day voyage, Liberty entered Rota, took on stores, equipment, additional linguists and technical personnel, and departed for the Eastern Mediterranean on June 2, 1967.

Officers and enlisted personnel on board the ship and those in supervisory positions expressed misgivings about the impending mission. Perhaps it was best expressed by Chief Petty Officer Raymond Linn, who was to retire at the end of June after 30 years’ service. He opined that it was foolhardy to send an unarmed ship, a spy ship, into such a potential maelstrom. Chief Linn proved all too prescient, as he would become one of 34 crewmen who would die in the attack. Others at higher levels expressed uncertainty, and Cdr. McGonagle made a request for a destroyer type escort. The request was denied for, among other reasons, the ship had every right to be where she was and was clearly identifiable as a United States Ship. Finally, it was assumed that the ship could withdraw from danger if need be.

The intensity of hostilities during what would become known the Six Day War was such that those higher up in the chain of command modified operational orders, not simply for USS Liberty, but for all Sixth Fleet ships. In summary, new orders stipulated that areas might be modified based on “the local situation” and that the Sixth Fleet Commander was to be advised by flash message of “any threatening actions to you or diversions from schedule necessitated by external threat.” These messages, and those restricting a closest point of approach to 20 (and later, 100) miles from the hostile coast, did not reach Liberty.

Prior to reaching the operating area, Cdr. McGonagle had met with Lt. Cmdr. Dave Lewis, Liberty’s Research Department director, to confirm that it was absolutely necessary to be as close to the Gaza Strip as set forward in orders to execute the mission. McGonagle had also instituted a “modified” weapons condition three steaming watch that placed ammunition and extra personnel at the forward .50 caliber gun mounts.

|

| A painting of USS Liberty, Oil on Silk; Artist Unknown; C. 1967. (Gift of Ms. Cindy McGonagle, Naval History and Heritage Command image) |

Liberty arrived off the city of El Arish, about 30 miles west of the Gaza Strip on the northern coast of the Sinai Peninsula, just after midnight on June 8th, 1967. There, a tale of bravery, perseverance and sacrifice, unique in the annals of the U.S. Navy, would play out. By late morning she had been overflown by multiple aircraft, both ungainly “flying boxcar” Noratlas 2501 types, and fighter bombers. One of the boxcars reportedly had Star of David markings. It was, in the words of one of the officers of the deck, Ens. John Scott, a beautiful day, and the American flag was clearly visible. All crewmembers later queried agreed that the flag was clearly visible prior to and during the attack. Some members of the crew even sunbathed on deck before a General Quarters drill was held at 1300 that afternoon.

About one hour later, a savage air attack began and in the words of then-Lieutenant George Golden, Liberty’s chief engineer, “all hell broke loose.” Repeated strafing by Mirage III fighters and Mystere fighter-bombers left the bridge in shambles, with the navigator dead, the executive officer mortally wounded, and the officer of the deck and the commanding officer severely wounded. The ship’s bridge area was in flames from burning napalm, and the superstructure was repeatedly penetrated by rocket fire. Years later, Golden recounted that three flags, including a large “holiday ensign,” were raised and shot away.(3) A shipyard survey later tabulated 821 holes made in Liberty’s hull, deck, and superstructure.

During the initial attack, the forward .50 caliber machine gun positions were destroyed and the crews killed. Communications antennae were destroyed, and the ship was quickly rendered defenseless and mute. The air assault was followed by a surface engagement in which three Israeli torpedo boats rapidly closed in and launched torpedoes, one of which made a 40-foot gash, starboard side amidships, flooding the Research Department spaces and killing all inside.

Amid the massive, sudden destruction, the well-trained crew responded with instinctive professionalism and consummate bravery. Lt. Richard Kiepfer, the ship’s doctor, rescued those wounded from exposed decks at great risk to himself. Helmsman Francis Brown remained at his post, despite heavy shelling, until he was killed by a projectile that struck him from behind. Executive Officer (XO) Phillip Armstrong was fatally injured by strafing as he jettisoned 50-gallon gasoline drums from the bridge. Everywhere crewmen performed gallantly, to include those initially temporarily overcome by fear. Dr. Kiepfer, though wounded himself, operated in a vain attempt to save Gary Blanchard, a young seaman from Kansas.

During the initial attack, radiomen were able to send a distress message which was received on board the carrier Saratoga (CVA 60) using jury rigged equipment, but the signal was jammed intermittently. Rescue ships and aircraft did not reach the ship during the long and perilous night. Cdr. McGonagle, fortified by black coffee and assisted by relays of underway officers of the deck, remained on the bridge guiding the ship at night by observing Polaris, for the gyrocompass had been rendered useless. Ens. John Scott, Damage Control Assistant, personally surveyed the ship, monitored damage reports from his subordinates and supervised shoring of the bulkheads of the research space to prevent its collapse.

USS Davis (DD 937), flagship for Commander, Destroyer Squadron Twelve (COMDESRONTWELVE), received message traffic suggesting that the Liberty had been attacked, and the ship responded to emergency orders of Commander Sixth Fleet that she proceeded at top speed, in company with USS Massey (DD 778), to the stricken ship some 500 miles away. At first light on June 9, the destroyers found, according to Lt. (later Rear Admiral) Paul Tobin, a powerless ship covered with marks of battle damage, scorch marks, and a ten degree starboard list. “The reality of the situation struck home as we climbed aboard and looked at the faces of the men,” wrote Lt. Hubert Strachwitz of the Davis in a letter to his wife. “No Hollywood makeup man nor actor could ever produce those faces,” he went on. “There were sunken eyes, bristly, dirty faces dark bloodstains, ripped clothes covered with oil and charcoal. There were no hysterics, no crying, no cursing—just tired bodies trying to do necessary jobs.”(4)

The major evolutions required were providing medical care for the wounded, removing the dead, restoring power and stability to the ship, so that the ship could reach a safe port. Capt. Harold Leahy, COMDESRON TWELVE, came aboard and climbed to the shattered bridge where the commodore gently offered to take command of the Liberty. After consulting with Dr. Kiepfer and Dr. Peter Flynn, a general surgeon airlifted to Massey from USS America (CVA 66), he chose not to with the understanding that the captain lay below to rest. Kiepfer opined then as he did later to the board of inquiry, that Capt. McGonagle was a key ingredient—a rock upon which the rest of the men supported themselves—in the survival of the Liberty. In so doing, he had earned the right to bring her safely into port. Lt. Tobin and Lt. Cmdr. William Pettyjohn, COMDESRONTWELVE chief of staff, came on board to give temporary assistance to the engineering force and assume the duties of executive officer.

The next pressing task was to restore power and stability to the ship. Lt. Tobin and Lt. Cmdr. Pettyjohn, together with the Liberty’s crew, augmented by engineering and damage control rates, began the daunting task. Later, Tobin observed that it was good to work with the crew, for they had detailed knowledge of the layout of the darkened ship and its equipment. He also recalled that they were infused with new energy by their newly arrived comrades.(5)

By careful study of data at hand, such as the liquid loading diagram, it was determined that the list could be corrected, and the transfer of remaining fuel to port tanks was successful. Concurrently, the propulsion plant was surveyed and electric power was gradually restored after a diesel generator was started and wiring repaired. The ship was determined to be as seaworthy as possible and it was shown that, although there was much freestanding water throughout the ship, there was sufficient righting arm to enable it to recover from rolls in heavy weather. It was thought that the keel was intact.(6)

After critical systems were restored and Liberty no longer seemed in danger of sinking, the decision was made to raise steam and make the transit to Malta, 1,000 miles away. Lt. Cmdr. Pettyjohn, acting as temporary XO, established regular steaming watches and a regular underway routine. As time elapsed, the ship’s operating systems, such as her gyroscopic compass and fire and flushing water, were restored. The restoration of lighting and ventilation had earlier brought about an improvement in morale and wellbeing. Liberty was accompanied by the ocean going tug USS Papago (ATF 160) whose crew recovered bodies that had drifted though the torpedo hole as well as classified materials. Except for one unnerving night, when the ship encountered heavy weather 150 miles from Malta, the transit was uneventful. Forward bulkheads in the vicinity of the flooded spaces warped and panted. The contents of the adjacent compartments were removed and jettisoned and additional shoring placed. The weather moderated, and on June 14, with Cdr. McGonagle on the bridge at the conn, the ship entered Grand Harbor, Valetta, Malta, with Fort Ricasoli on the port beam.

Liberty spent the mid-summer of 1967 dry docked in Malta, where the remains of those who died in the Research Department spaces were removed, and a board of inquiry under Rear Admiral Isaac S. Kidd, Jr., was convened. A new permanent XO, Lt. Cmdr. Donald L. Burson, formerly the operations officer in USS Aucilla (AO 56), a Norfolk-based fleet oiler, arrived to replace Lt. Cmdr. Philip Armstrong, who had been killed in the attack.(7) It was a period for recollection of the ordeal, decompression and relaxation, as well as poignant tasks such as writing to the survivors of those lost, undertaken in an instinctively kind, gentle way by the skipper, assisted by Ens. Patrick O’Malley. The chief engineer, Lt. George Golden, remembered that when he and the skipper went to a party, the captain expressed some reluctance to leave, and when he did return to his room, “wept.”(8) Liberty left Valetta in company with Papago and arrived at Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek on July 29, 1967.

William McGonagle, as noted, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on June 11, 1968, after his promotion to captain. The newspaper account of the ceremony noted that after Navy Secretary Ignatius placed the award around his neck, McGonagle “wept.”(9) Three days later, he travelled to Norfolk Naval Shipyard, where Liberty was moored, pending a decision about her future. He conferred various awards, such as silver stars and the bronze star, to surviving crew members for heroism under fire. Others had already left the command. The magnitude of the crew’s bravery is evinced by the sheer number of personal awards given after Liberty’s return: one medal of honor, two navy crosses, 11 silver stars, nine navy commendation medals, and 204 purple hearts among a crew of 294.(10)

Liberty’s final act occurred on June 28, 1968, when she was decommissioned. Under clear skies, Lt. Cmdr. Burson, who had relieved Capt. McGonagle, gave brief remarks and Capt. Charles J. Beers, commander of the Inactive Ships Maintenance Facility, read the inactivation orders, the colors were lowered, and the 83 remaining crew members left the ship. (11)

Demise of Surface Intelligence Collection

The decommissioning occurred about five months after the capture of the USS Pueblo (AGER 2) while conducting a similar intelligence gathering mission off the North Korean coast. The crew was interned under brutal conditions for nearly a year. Two such episodes so close together impaired the prestige and standing of the United States and exposed brave crews to death and extended torture. The court of inquiry on the Pueblo incident, in contrast to the Liberty board of inquiry conducted by Rear Adm. Kidd, conducted lengthy deliberations and uncovered defects in program execution, such as lack of a plan to assist the ship in the case of unanticipated emergency. The most telling flaw was the assumption that ships engaged in such sensitive operations in international waters were immune from interference. The abrupt collapse of that assumption led Navy Secretary John Chafee to set aside the recommended court martial for the Pueblo’s commanding officer and punishments for those higher in the chain of command. The AGTR and AGER programs were eliminated, and Lt. Cmdr. Burson went from being the last commanding officer of USS Liberty to also being the last commanding officer of USS Palm Beach (AGER 3), which was stricken from the Navy Register on December 1, 1969

For Many, a Catastrophe without Closure

The end of the Liberty’s short career as a “spy ship” and the denouement of much of the Navy’s surface intelligence gathering activities came about two years after the attack. In its wake, uncertainty and residual bitterness remained among former Liberty crewmembers, including Capt. McGonagle, those who conducted the investigation, and former high-ranking government officials such as Secretary of State Dean Rusk. The attack was savage and repeated against key defensive and ship control/communications spaces and facilities. Liberty was much larger than the SS Quseir, the Egyptian livestock carrier for which the Israeli government concluded she had been mistaken. The question remains, why would such assets have been used against a livestock ship? The best summation of the attack was perhaps made by retired Rear Adm. Paul Tobin, who played a key role in steaming the ship to Malta. He pointed out that the Israeli attack was made against a ship that was in international waters, was freshly painted, had large, clearly painted hull beading and was adorned with sophisticated antennae. To Tobin, it was unbelievable that unsupervised pilots made repeated attacks on a defenseless ship.(12) It must be the governing evaluation until and unless the government of the State of Israel makes a truthful disclosure of the facts, as Capt. McGonagle requested in an excellent oral history conducted by former Naval History and Heritage Command historian Tim Frank, two years before McGonagle’s death in 1999.

|

| A privately-produced button in the collection of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (Courtesy of Richard K. Smith, 1978) |

The attack on the ship and her brave crew and its residuals may have one overriding meaning. It is, as a Norfolk Virginian-Pilot editorial page writer opined in July, 1967, that “the arrival here today of the USS Liberty is a sobering reminder to this Navy community that no ship that clears this port is assured of returning with her hull intact and all her crewmen alive and uninjured….”(13)

Notes:

- “Liberty Skipper Gets Medal of Honor,” New York Times, June 12, 1968, 4.

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Liberty III (AGTR 5), 1964-1970

- Descriptions of the attack and its aftermath were in part taken from a tape recording of an oral presentation by Lt. Cmdr. George Golden, USN (Ret.) to an audience at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum. The tape was found and the contents abstracted by the author.

- James Scott, Attack on the Liberty (Simon and Schuster, 2009), 127.

- The order and priority of tasks that had to be accomplished are set forward in a thorough professional note written by then-Cdr. Paul Tobin, USN. This note was contained in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings in December, 1978. Rear. Adm. Tobin shared further details with the author in a telephone interview on April 6, 2017.

- Telephone interview with Rear Adm. Paul Tobin by the author, April 6, 2017.

- In an e-mail to the author Cdr. Burson noted that his tour was a “learning experience.”

- See Note 3.

- See Note 1.

- “Retiring ‘Liberty,’ But Mostly Her Men, Honored,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, June 15, 1968, 7.

- “‘Liberty’ Flag Lowered,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, June 29, 1968, 13.

- The Liberty Incident: The 1967 Israeli Attack on the U.S. Spy Ship, Book Review by Rear Adm. Paul Tobin, USN (Ret), U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, August 2002.

- “Welcome Liberty,” editorial, Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 29, 1967, 8.

About the author: Captain Alexander “Sandy” Monroe, a retired surface warfare officer, is the author of official histories on U.S. Atlantic Command counternarcotic operational assistance to civilian law enforcement agencies and the treatment of Haitian asylum seekers at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He was also dispatched to the Arabian Gulf on assignment for the director of naval history during Operation Earnest Will.

How big is a 45-90 bullet?

Declaring “a right delayed is a right denied,” the Second Amendment Foundation’s Alan Gottlieb recently announced a lawsuit — this outfit specializes in legal action, some 50 currently underway around the country — challenging California’s 10-day waiting period on firearms purchases.

Gottlieb has a point. Why should any law-abiding citizen have to wait more than a week to take delivery of a firearm he or she has a constitutionally protected right to have?

By no small coincidence, the California lawsuit came about the same time Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, a perennial gun control advocate, was signing legislation setting a 10-day waiting period for gun purchases in the Evergreen State. Nobody has ever provided a rational justification for making gun buyers wait for any length of time to buy a firearm.

Anti-gunners only think they’ve provided good reasons: It’s a “cooling off” period so somebody doesn’t a) shoot their neighbor, b) shoot their spouse or “significant other,” or, c) shoot themselves. It allows for an “expanded background check” so government can determine whether the buyer is preparing to, a) rob a bank, b) stage a mass shooting.

All of this is pretty much nonsense, and waiting period proponents know it. What may really be at work here is one more hoop through which citizens must jump as government tries to convince us the Second Amendment is a regulated privilege.

Joining SAF are the North County Shooting Center, San Diego County Gun Owners PAC, California Gun Rights Foundation, Firearms Policy Coalition, PWGG LLP, John Phillips, Alisha Curtin, Dakota Adelphia, Michael Schwartz, Darin Prince and Claire Richards. They are represented by attorneys Bradley A. Benbrook and Stephen M. Duvernay at Benbrook Law Group in Sacramento. Defendants are Attorney General Rob Bonta and Allison Mendoza, director of the California Department of Justice, Bureau of Firearms, in their official capacities. The case is known as Richards v. Bonta and it was filed in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California.

“There is nothing in the Second Amendment about waiting more than a week in order to exercise the right to keep and bear arms,” Gottlieb said. “California’s waiting period relegates the Second Amendment to the status of a government-regulated privilege, in direct conflict to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declared in its 2008 Heller ruling that the Second Amendment is not a second-class right, subject to an entirely different body of rules than the other Bill of Rights guarantees.”

And it goes a little deeper, he explained.

“There’s a Fourteenth Amendment aspect to this case,” Gottlieb added. “The state broadly discriminates against average citizens by allowing exemptions to nearly two-dozen categories of favored individuals who can take possession of firearms without having to endure the delay, which violates the Equal Protection clause. We’re hoping to bring this practice to an end.”

“Really Silly”

SAF Executive Director Adam Kraut, himself a practicing attorney, noted the Golden State’s waiting period restriction “isn’t analogous to any constitutionally relevant history and tradition of regulating firearms.” His criticism of California’s waiting period didn’t stop there.

“Where this really gets silly,” he observed at the time the lawsuit was filed, “is when the waiting period restriction even applies to a gun buyer who already owns other firearms. Not to mention, those who are looking to acquire a firearm for protection immediately do not have the luxury of waiting 10 days. Long story short, the state’s 10-day waiting period must be declared unconstitutional and enjoined, which is the purpose of our lawsuit. We’re asking the court for injunctive and declaratory relief.”

The Double Standard

It has often been said about liberals that if they didn’t have the double standard, they’d have no standards at all.

Case in point: Last month, in the aftermath of a highly publicized mass shooting at a mall in the Dallas suburb of Allen, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz commented on Twitter that he was “praying” for the families of the victims.

“Heidi and I are praying for the families of the victims of the horrific mall shooting in Allen, Texas,” Cruz wrote. “We pray also for the broader Collin County community that’s in shock from this tragedy.”

Typical of the gun control crowd lately, Cruz was pilloried for his remark, according to The Guardian.

The backlash included nasty remarks from various anti-gunners, including Shannon Watts, founder of the gun prohibition group Moms Demand Action. Her Twitter message was blunt: “YOU helped arm him (the gunman) with guns, ammo and tactical gear. He did exactly what you knew he’d do. Spare us your prayers and talk of justice for a gunman who is … dead.”

Funny thing about shooting one’s mouth off on social media; you occasionally shoot yourself in the foot. To wit: About the same time Cruz was talking about remembering the victims in his prayers, Joe Biden was releasing a statement from the White House in which he announced, “Jill and I are praying for their families and for others critically injured, and we are grateful to the first responders who acted quickly and courageously to save lives.”

Apparently, Watts and other Cruz critics had used up all of their righteous indignation and had none left over for their guy in the Oval Office.

Took ‘Em a While

Following the shooting, Texas lawmakers moved a piece of legislation raising the minimum age for purchasing a semiautomatic rifle in the Lone Star State. It’s something which has happened in other states over the past couple of years, and the effort started in Texas following last year’s grade school attack in Uvalde.

The Texas Tribune reported on the legislative action, but waited a whole eight paragraphs into the story before acknowledging something which should have been right up front. Raising the minimum age would have had no impact (that’s zero, zip, nada) on the Texas mall killer.

“Because the man identified as the gunman in Allen was 33, raising the age limit for semi-automatic rifle purchases likely wouldn’t have kept him from purchasing such a weapon,” the newspaper admitted.

More Hypocrisy

Readers might recall another tragic mass killing in Texas just 24 hours after the mall shooting, but then, again, perhaps not because this was different.

Where eight people died at the Dallas-area mall, eight more people were killed when a guy ran over them with an SUV in Brownsville as they were waiting at a bus stop. The aforementioned Alan Gottlieb, this time speaking on behalf of the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, had some timely observations.

“Brownsville was just the latest outrage which proves people intent on … mayhem don’t always use firearms,” he said, “but in none of these cases has anyone ever tried to blame, and then ban, motor vehicles. Yet, the victims are just as dead.”

He’s got a point. Early in my career, I frequently was called upon by the Washington State Patrol to photograph fatal accident scenes in the mountain country east of Seattle, primarily along Interstate 90. In those days, troopers didn’t have cameras, so they needed somebody to handle the chore and, as the editor of the local newspaper, I had a camera. I lost count of the number of fatal accidents to which I responded.

Gottlieb said motor vehicles were “the new assault weapons the gun banners don’t want to ban.” He ran down a short list of mass murders (by the gun control formula of more than four victims) committed in recent years with motor vehicles.

“Remember the six people murdered by Darrell E. Brooks when he drove an SUV through the annual Christmas parade in Waukesha, Wisconsin in 2021,” Gottlieb noted. “Sixty-two other people were injured in that rampage.

“Eight people were killed on a New York City bike path in 2017 when an Islamic extremist deliberately ran them down with a rented pickup truck,” he continued. “The driver was punished, not every truck owner in America.

“Who can forget the 2016 mass murder in Nice, France when a man drove a large truck into a crowd celebrating Bastille Day,” Gottlieb recalled. “He killed 84 people and injured hundreds more.”

In each of these cases, the perpetrator was held responsible. Their choice of weapon was never demonized in the media the same way firearms have been singled out.