Category: Well I thought it was neat!

By Colonel James E. Moschgat, Commander of the 12th Operations Group, 12th Flying Training Wing, Randolph Air Force Base, Texas

William “Bill” Crawford certainly was an unimpressive figure, one you could easily overlook during a hectic day at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Mr. Crawford, as most of us referred to him back in the late 1970s, was our squadron janitor.

While we cadets busied ourselves preparing for academic exams, athletic events, Saturday morning parades and room inspections, or never-ending leadership classes, Bill quietly moved about the squadron mopping and buffing floors, emptying trash cans, cleaning toilets, or just tidying up the mess 100 college-age kids can leave in a dormitory. Sadly, and for many years, few of us gave him much notice, rendering little more than a passing nod or throwing a curt, “G’morning!” in his direction as we hurried off to our daily duties.

Why? Perhaps it was because of the way he did his job-he always kept the squadron area spotlessly clean, even the toilets and showers gleamed. Frankly, he did his job so well, none of us had to notice or get involved. After all, cleaning toilets was his job, not ours. Maybe it was is physical appearance that made him disappear into the background. Bill didn’t move very quickly and, in fact, you could say he even shuffled a bit, as if he suffered from some sort of injury. His gray hair and wrinkled face made him appear ancient to a group of young cadets. And his crooked smile, well, it looked a little funny. Face it, Bill was an old man working in a young person’s world. What did he have to offer us on a personal level?

Finally, maybe it was Mr. Crawford’s personality that rendered him almost invisible to the young people around him. Bill was shy, almost painfully so. He seldom spoke to a cadet unless they addressed him first, and that didn’t happen very often. Our janitor always buried himself in his work, moving about with stooped shoulders, a quiet gait, and an averted gaze. If he noticed the hustle and bustle of cadet life around him, it was hard to tell. So, for whatever reason, Bill blended into the woodwork and became just another fixture around the squadron. The Academy, one of our nation’s premier leadership laboratories, kept us busy from dawn till dusk. And Mr. Crawford…well, he was just a janitor.

That changed one fall Saturday afternoon in 1976. I was reading a book about World War II and the tough Allied ground campaign in Italy, when I stumbled across an incredible story. On September 13, 1943, a Private William Crawford from Colorado, assigned to the 36th Infantry Division, had been involved in some bloody fighting on Hill 424 near Altavilla, Italy. The words on the page leapt out at me: “in the face of intense and overwhelming hostile fire … with no regard for personal safety … on his own initiative, Private Crawford single-handedly attacked fortified enemy positions.” It continued, “for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life above and beyond the call of duty, the President of the United States …”

“Holy cow,” I said to my roommate, “you’re not going to believe this, but I think our janitor is a Medal of Honor winner.” We all knew Mr. Crawford was a WWII Army vet, but that didn’t keep my friend from looking at me as if I was some sort of alien being. Nonetheless, we couldn’t wait to ask Bill about the story on Monday. We met Mr. Crawford bright and early Monday and showed him the page in question from the book, anticipation and doubt in our faces. He starred at it for a few silent moments and then quietly uttered something like, “Yep, that’s me.”

Mouths agape, my roommate and I looked at one another, then at the book, and quickly back at our janitor. Almost at once we both stuttered, “Why didn’t you ever tell us about it?” He slowly replied after some thought, “That was one day in my life and it happened a long time ago.”

I guess we were all at a loss for words after that. We had to hurry off to class and Bill, well, he had chores to attend to. However, after that brief exchange, things were never again the same around our squadron. Word spread like wildfire among the cadets that we had a hero in our midst-Mr. Crawford, our janitor, had won the Medal! Cadets who had once passed by Bill with hardly a glance, now greeted him with a smile and a respectful, “Good morning, Mr. Crawford.”

Those who had before left a mess for the “janitor” to clean up started taking it upon themselves to put things in order. Most cadets routinely stopped to talk to Bill throughout the day and we even began inviting him to our formal squadron functions. He’d show up dressed in a conservative dark suit and quietly talk to those who approached him, the only sign of his heroics being a simple blue, star-spangled lapel pin.

Almost overnight, Bill went from being a simple fixture in our squadron to one of our teammates. Mr. Crawford changed too, but you had to look closely to notice the difference. After that fall day in 1976, he seemed to move with more purpose, his shoulders didn’t seem to be as stooped, he met our greetings with a direct gaze and a stronger “good morning” in return, and he flashed his crooked smile more often. The squadron gleamed as always, but everyone now seemed to notice it more. Bill even got to know most of us by our first names, something that didn’t happen often at the Academy. While no one ever formally acknowledged the change, I think we became Bill’s cadets and his squadron.

As often happens in life, events sweep us away from those in our past. The last time I saw Bill was on graduation day in June 1977. As I walked out of the squadron for the last time, he shook my hand and simply said, “Good luck, young man.” With that, I embarked on a career that has been truly lucky and blessed. Mr. Crawford continued to work at the Academy and eventually retired in his native Colorado where he resides today, one of four Medal of Honor winners living in a small town.

A wise person once said, “It’s not life that’s important, but those you meet along the way that make the difference.” Bill was one who made a difference for me. While I haven’t seen Mr. Crawford in over twenty years, he’d probably be surprised to know I think of him often. Bill Crawford, our janitor, taught me many valuable, unforgettable leadership lessons. Here are ten I’d like to share with you.

- Be Cautious of Labels. Labels you place on people may define your relationship to them and bound their potential. Sadly, and for a long time, we labeled Bill as just a janitor, but he was so much more. Therefore, be cautious of a leader who callously says, “Hey, he’s just an Airman.” Likewise, don’t tolerate the O-1, who says, “I can’t do that, I’m just a lieutenant.”

- Everyone Deserves Respect. Because we hung the “janitor” label on Mr. Crawford, we often wrongly treated him with less respect than others around us. He deserved much more, and not just because he was a Medal of Honor winner. Bill deserved respect because he was a janitor, walked among us, and was a part of our team.

- Courtesy Makes a Difference. Be courteous to all around you, regardless of rank or position. Military customs, as well as common courtesies, help bond a team. When our daily words to Mr. Crawford turned from perfunctory “hellos” to heartfelt greetings, his demeanor and personality outwardly changed. It made a difference for all of us.

- Take Time to Know Your People. Life in the military is hectic, but that’s no excuse for not knowing the people you work for and with. For years a hero walked among us at the Academy and we never knew it. Who are the heroes that walk in your midst?

- Anyone Can Be a Hero. Mr. Crawford certainly didn’t fit anyone’s standard definition of a hero. Moreover, he was just a private on the day he won his Medal. Don’t sell your people short, for any one of them may be the hero who rises to the occasion when duty calls. On the other hand, it’s easy to turn to your proven performers when the chips are down, but don’t ignore the rest of the team. Today’s rookie could and should be tomorrow’s superstar.

- Leaders Should Be Humble. Most modern day heroes and some leaders are anything but humble, especially if you calibrate your “hero meter” on today’s athletic fields. End zone celebrations and self-aggrandizement are what we’ve come to expect from sports greats. Not Mr. Crawford-he was too busy working to celebrate his past heroics. Leaders would be well-served to do the same.

- Life Won’t Always Hand You What You Think You Deserve. We in the military work hard and, dang it, we deserve recognition, right? However, sometimes you just have to persevere, even when accolades don’t come your way. Perhaps you weren’t nominated for junior officer or airman of the quarter as you thought you should – don’t let that stop you.

- Don’t pursue glory; pursue excellence. Private Bill Crawford didn’t pursue glory; he did his duty and then swept floors for a living. No job is beneath a Leader. If Bill Crawford, a Medal of Honor winner, could clean latrines and smile, is there a job beneath your dignity? Think about it.

- Pursue Excellence. No matter what task life hands you, do it well. Dr. Martin Luther King said, “If life makes you a street sweeper, be the best street sweeper you can be.” Mr. Crawford modeled that philosophy and helped make our dormitory area a home.

- Life is a Leadership Laboratory. All too often we look to some school or PME class to teach us about leadership when, in fact, life is a leadership laboratory. Those you meet everyday will teach you enduring lessons if you just take time to stop, look and listen. I spent four years at the Air Force Academy, took dozens of classes, read hundreds of books, and met thousands of great people. I gleaned leadership skills from all of them, but one of the people I remember most is Mr. Bill Crawford and the lessons he unknowingly taught. Don’t miss your opportunity to learn.

Bill Crawford was a janitor. However, he was also a teacher, friend, role model and one great American hero. Thanks, Mr. Crawford, for some valuable leadership lessons.

Dale Pyeatt, Executive Director of the National Guard Association of Texas, comments: And now, for the “rest of the story”: Pvt William John Crawford was a platoon scout for 3rd Platoon of Company L 1 42nd Regiment 36th Division (Texas National Guard) and won the Medal Of Honor for his actions on Hill 424, just 4 days after the invasion at Salerno.

On Hill 424, Pvt Crawford took out 3 enemy machine guns before darkness fell, halting the platoon’s advance. Pvt Crawford could not be found and was assumed dead. The request for his MOH was quickly approved. Major General Terry Allen presented the posthumous MOH to Bill Crawford’s father, George, on 11 May 1944 in Camp (now Fort) Carson, near Pueblo. Nearly two months after that, it was learned that Pvt Crawford was alive in a POW camp in Germany. During his captivity, a German guard clubbed him with his rifle. Bill overpowered him, took the rifle away, and beat the guard unconscious. A German doctor’s testimony saved him from severe punishment, perhaps death. To stay ahead of the advancing Russian army, the prisoners were marched 500 miles in 52 days in the middle of the German winter, subsisting on one potato a day. An allied tank column liberated the camp in the spring of 1945, and Pvt Crawford took his first hot shower in 18 months on VE Day. Pvt Crawford stayed in the army before retiring as a MSG and becoming a janitor. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan officially presented the MOH to Bill Crawford.

William Crawford passed away in 2000. He is the only U.S. Army veteran and sole Medal of Honor winner to be buried in the cemetery of the U.S. Air Force Academy.

https://youtu.be/3pTFYBL96ZY

Yeah I know this is suppose to be a Gun Blog. But I just could not resist posting my favorite Cartoon of yesteryear! Grumpy

The Great War was notable for the carnage that resulted when 19th-century military tactics were pitted against 20th-century infantry arms—such as machine guns, poison gas and flame throwers—which were used by all belligerent nations. There was, however, one infantry arm employed in the war that was uniquely American: the shotgun.

Although shotguns had been used by individuals in the U.S. military for over 100 years, the guns were generally privately owned arms. After the Civil War, a few shotguns were again employed during the so-called “Indian Wars.” The U.S. Army procured a relatively small number of shotguns for “foraging” use, but some privately owned shotguns also saw action during that period. The use of shotguns for deadly serious purposes was well-ingrained in the American psyche as aptly related in a 1920s article published in Harper’s Pictorial:

“… [The shotgun] is not a new man-killing arrangement. For years, the sawed-off shotgun has been the favorite weapon of the American really out gunning for the other fellow or expecting the other fellow to come a-gunning for him.”

Despite the well-known effectiveness of shotguns for certain situations, the first procurement of shotguns specifically for combat use by the U.S. military did not occur until the dawn of the 20th century. Circa 1900, the U.S. Army purchased an estimated 200 Winchester Model of 1897 slide- action repeating shotguns for use in the on-going “pacification” campaigns in the Philippine Islands following the Spanish-American War of 1898.

There was a clear need for an arm to help battle the fierce Moro tribesmen, who were exacting a deadly toll on American troops in close-quarters combat. It was recognized that a short-barreled, 12-ga. shotgun loaded with 00 buckshot was the most formidable tool available for such applications. These “sawed off” shotguns soon proved their mettle and were used with notable effectiveness in the Philippines.

When the United States entered World War I in the spring of 1917, General John Pershing and the U.S. Army General Staff were determined not to repeat the same mistakes that were made by both sides during the previous three years of the war. As stated in an American Rifleman article published after the war:

“When the A.E.F. began to take over portions of the front lines it brought with it General Pershing’s predetermined decision to break up the enemy’s use of its trenches as take-off points for such assaults, to destroy such attacking ‘shock troops’ as they came on, and so to compel the open-ground warfare for which Europeans had little liking but which was wholly in the character of the American spirit and in which it was foreseen the latter would give an extremely effective account of themselves.”

The new tactics that were to be employed by the American “Doughboys” required new arms. Many of the senior officers of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), including Gen. Pershing, had previously served in the Philippines and had first-hand knowledge of the effectiveness of the shotgun. It was soon recognized that they possessed much potential for both offensive and defensive trench warfare.

The U.S. Army Ordnance Department was ordered to evaluate which shotgun would best suit the needs of the American troops deploying to France. The consensus was that the Winchester Model 1897 would be the logical choice. The Model 1897, later designated the “M97,” was a reliable gun that had been around for some 20 years and had acquitted itself well in the Philippines.

The variant of the Model 1897 selected by the Ordnance Department had a solid frame (non-takedown) with a riot-length (20”) cylinder bore barrel. The gun had a total capacity of six rounds (five in the magazine and one in the chamber) and lacked a disconnector. This meant that it could be fired by holding down the trigger while rapidly manipulating the slide, which resulted in a high rate of fire when used in that manner.

While a 20”-barreled Model 1897 shotgun could be obtained literally “off the shelf” from Winchester, the Ordnance Department stipulated that the new combat shotgun must be capable of mounting a bayonet. Although that may appear to have been a simple requirement, it posed some vexing problems. While the typical rifle barrel was small enough in diameter to permit it to fit inside a bayonet guard ring, the large diameter of a 12-ga. shotgun’s bore precluded that method of attachment. The problem was solved by the use of an offset bracket attached to the end of the barrel for attachment of the bayonet.

Another problem to overcome was the fact that a shotgun’s barrel would become extremely hot after firing only a few rounds. Since it would be impossible to effectively wield a bayonet without being able to firmly grasp the barrel, some form of protection was required. A ventilated metal handguard was designed that allowed air circulation between the guard and barrel and permitted a bare hand to control a hot barrel. Springfield Armory worked in conjunction with Winchester on the design of a handguard/bayonet adapter assembly. In a relatively short period of time, the proposed new combat shotgun was officially adopted.

The new arm, soon dubbed the “trench gun,” was given the ordnance code designation number “G-9778-S.” The guns were typically hand-stamped with a “US” and “flaming bomb” marking on the right sides of the receivers in front of the ejection ports to signify acceptance by the U.S. Army Ordnance Department.

The new “trench gun” was designed to be used with the M1917 “U.S. Enfield” rifle bayonet, presumably because there were larger numbers on hand as compared to the M1905 bayonet used with the M1903 Springfield rifle. The fact that Winchester was also making the M1917 bayonet at that time may also have played a role in its selection. The new trench gun was fitted with sling swivels that permitted the use of standard service rifle slings, primarily the leather M1907 sling. The guns were initially issued with commercial-production paper-case 00 buckshot ammunition.

As shotguns were not previously in the Army’s Tables of Organization and Equipment (TO&E), limited numbers were issued to selected infantry units in France for preliminary field testing and evaluation. An Ordnance Department memo dated June 8, 1918, stated:

“… 1,000 shotguns, referred to herewith, together with ammunition are now available in Depots in France … . Instructions are requested regarding the issue and distribution of these weapons. It is suggested that they may prove a most valuable arm for the use of raiding parties, and that a practical test be made in the 26th and 42nd Divisions, and that full information be furnished this office within 30 days, showing the difficulties experienced in maintenance, the susceptibility to jam under trench conditions, and the effectiveness of the weapon. Fifty guns should be issued to each Division mentioned above, with 100 rounds of ammunition per gun … .”

Other divisions that were issued trench guns during the war included the 5th, 26th, 32nd, 35th, 42nd, 77th and 82nd. Most of the reports from the units that were issued trench guns for preliminary testing were positive in nature. Typical responses included: “It is the general opinion of those who have used shotguns that they are effective weapons for scouting and patrolling purposes. Col. H.J. Hunt, Sixth Infantry,” and “Shotguns in this regiment have given very satisfactory results. Their effectiveness at short ranges, on raids and patrols makes them a most desirable weapon, and I would recommend that they be adopted. Captain H.P. Blanks, 61st Infantry.”

The most common complaints against shotguns pertained to the propensity of the paper-cased ammunition to become wet in the muddy trench environment, which could cause the shells to swell and become unusable. The lack of belts or pouches to carry the shells was also cited as a problem in several reports. This was discussed in a post-World War I American Rifleman article:

“[I]n the trenches the cartons (of shotgun shells) were set on the long shelf under the parapet … and the doughboys would put a couple of handfuls in their breeches pockets, just as they were accustomed to ‘at home on the farm.’”

Canvas looped shotshell belts were considered for use with the guns but were not the optimum method of carrying shotgun shells in the constantly damp and muddy trenches. A canvas pouch with internal loops (holding 32 rounds) and a shoulder sling was designed and procured to carry trench gun ammunition, but few were likely sent overseas before the Armistice.

Since the major culprit was the paper-cased shells, all-brass 00 buckshot ammunition was ordered. Such ammunition would be less susceptible to moisture and could better withstand the battering from constant loading and unloading of the guns. Some of the all-brass buckshot ammunition of that era was characterized by an unusual “saw tooth” crimp.

U.S. Ordnance Department records indicate that Winchester delivered 19,196 Model 1897 trench guns to the government during the First World War. It is likely that several thousand more guns were procured from wholesalers and jobbers for conversion to trench guns during that period, and, perhaps, as many as 25,000 M1897 trench guns were eventually manufactured during the war. World War I Winchester Model 1897 trench guns were serially numbered in three “blocks”: E433144-E474130; E514382-E566857; and E613303-E697066.

These blocks were obtained from ordnance documents and reports, and some slight variance on either side of the ranges may be expected. Most of World War I M1897 trench guns were in the third block of serial numbers.

In order to augment the supply of combat shotguns, the Ordnance Department contracted with the Remington Arms Co. for a trench gun variant of its Model 10 12-ga. shotgun. The Model 10 was a hammerless slide-action repeater that loaded and ejected from a port in the bottom of the receiver. Rather than utilizing the metal handguard/bayonet adapter assembly of the Winchester Model 1897 trench gun, the Remington Model 10 trench gun was designed with a metal bayonet adapter that clamped on the end of the barrel and a separate wooden handguard. The Model 10 adapter was also designed for use with the M1917 bayonet, which was also manufactured by Remington during that period.

The Model 10 trench gun had a 231⁄2” barrel and was fitted with sling swivels. The guns were stamped with a “US” and “flaming bomb” insignia on the left sides of the receivers. Remington delivered 3,500 Model 10 trench guns to the government during World War I. The serial number range of World War I military Model 10 trench guns was 128000-166000. Again, this is an approximate range and some slight variance on either side is possible.

In addition to the trench guns, the Ordnance Department purchased a quantity of Winchester Model 1897 and Remington Model 10 “riot guns.” These differed from the trench guns in that they were not fitted with bayonet adapter/handguard assemblies and did not have sling swivels. While some combat use cannot be ruled out, the riot guns were primarily intended to be utilized for guarding prisoners and similar duties.

As increasing numbers of the trench guns began to be deployed to the front-line trenches, their effectiveness became apparent. There were numerous references to the efficiency of the shotguns.

A post-war American Rifleman article contained the following statement regarding a U.S. Army officer: “[H]is men had one good chance with them (shotguns) at a German mass assault upon his trench—a charge obviously intended to overwhelm the defenders with its solid rush of men. (They) let them come on; and when those shotguns got going—with nine .34 caliber buckshot per load, 6 loads in the gun, 200-odd men firing, plenty more shells at hand—the front ranks of the assault simply piled up on top of one awful heap of buckshot-drilled men.”

Laurence Stallings related the following in his classic book, The Doughboys: “[A] Chicago sergeant, undergoing much hostile fire to reach a concrete pillbox, made his entrance through the stage door of the pestiferous machine-gun nest bearing a sawed-off shotgun. Two buckshot blasts and the twenty-three performers left on their feet surrendered.”

The shotgun’s effectiveness did not go unnoticed by the German government, which viewed the use of shotguns as a serious breach of international rules of warfare and lodged an official protest on September 14, 1918. The Germans sent a telegram to U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing, which stated, in part: “The German Government protests against the use of shotguns by the American Army and calls attention to the fact that, according to the laws of war, every prisoner found to have in his possession such guns or ammunition belonging thereto forfeits his life.”

The Germans were referring to a passage in the Hague Decrees, predecessor of the Geneva Convention, which stated, “It is especially forbidden to employ arms, projections, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.” The Kaiser’s minions also sought to exploit the issue for propaganda purposes, and several German newspapers wrote scathing editorials against this “barbaric” weapon.

For example, the Cologne Gazette opined that “… tommy-hawks and scalping knives would soon make their appearance on the American front … ,” and stated that “… Americans are not honorable warriors.” The Weser Zeitung newspaper was of the opinion that “… the barbarous shotguns have not been served out because they are likely to be effective but because the ill-trained Americans cannot use rifles and are badly supplied with machine guns.” It is reported that some of our Doughboys were rather amused by these editorial rants!

The United States government’s response to the German threat was swift and to the point. Secretary Lansing firmly replied that the use of shotguns was most assuredly not prohibited by the Hague Decrees or any other international treaty. He also made it known that if the Germans carried out their threats in even a “single instance” the American government knew what to do in the way of reprisals and stated that “notice is hereby given of the intention to make such reprisals.”

As correctly summed up in an American Rifleman article after the war: “Uncle Sam did not intend to have his trench-gunners massacred simply because he had given them a weapon which even the pick of the Prussian ‘shock troops’ dreaded more than anything that four years of war had called on them to face.”

Apparently, the American response had the desired effect as there is no indication that the Germans ever executed any Doughboys for possessing a shotgun or shotgun shells. It is perplexing as to why the Germans, who introduced and regularly used poison gas and flamethrowers, were so incensed about our use of shotguns. It is probable that the enemy actually feared the American behind the shotgun as much as the shotgun itself.

The United States considered the matter closed and continued to send trench guns to France as fast as production and shipping permitted. As stated in a publication after the war: “The shotguns went right on at their business—so terrible a success that message after message from G.H.Q. to America begged: ‘Give us more shotguns!’”

In addition to use in trench warfare and for guarding prisoners, some shotguns were reportedly employed in front-line positions in an attempt to deflect incoming German grenades. Some have questioned whether this actually occurred, but a number of World War I and post-World War I accounts confirm this practice.

A post-war American Rifleman article stated: “An interesting if amazing purpose which these guns (trench guns) were supposed to serve was that of shooting from the trenches, a la trapshooting, at hand-grenades, ‘potato mashers,’ and the like thrown over by the enemy, with a view to knocking such missiles back, to fall and explode outside the parapet. The procedure was taught and practiced at training camps during the war, using dummy Mills bombs as the aerial targets.”

Due to extensive use prior to World War II, original World War I Winchester and Remington trench guns are scarce today and are coveted by martial arms collectors. All World War I-era shotguns were originally blued, and any Parkerized examples have been refinished, possibly as part of a later arsenal overhaul.

A number of 1918 vintage M1897 trench guns may be encountered today without martial markings. The most logical explanation for such guns is that they were purchased by the government during World War I but the war ended before the guns could be issued, thus they were not stamped with the “US” and “flaming bomb” markings.

The popularity of shotguns is not restricted to collectors. Modern combat shotguns are in front-line use by American troops today—just as they were in the trenches of France more than 100 years ago. The shotgun is still a uniquely American combat arm. In certain combat applications, it is a fearsome arm with unquestioned effectiveness, just as the Kaiser’s troops first discovered in 1918 “in the trenches.”

The “crappy” Mark 14 Torpedo and the effect it had on the American Sub Force.

I had ran across this article on the internet doing research on something else, it discussed the torpedo debacle that the American Submarines had and to a lesser extent, the American Torpedo planes had because they basically were using the same technology and systems. It was very enlightening to see the bureaucratic stalling and shafting the sub crews and skippers who tried to tell BuOrd that their torpedoes sucked, whereas the Japanese had the awesome Long Lance torpedoes and their air arm had their own effective air dropped version. The Pics are complements of “Google”.

Fizzling fish, wrong tactics and incompetent commanders — ingredients for disaster simmering below the waves aboard American submarines — how many years did they add to World War II?

A strong case has been made, by authors as varied as Jim Dunnigan, John Keegan and George Friedman, that the leading cause of the eventual defeat of the Japanese in World War II was the choke hold on its commercial shipping achieved by the Allies. Friedman, in his thought provoking if flawed The Coming War With Japan, argues that aerial strategic bombing had little effect on Japanese production capacity. But production capacity is useless without raw materials. US submarines, ranging on the north-south routes from the Indies and along the Japanese coast, systematically interdicted the flow of strategic materials. By the end of the war Japanese imports of bulk commodities such as iron ore and oil had plunged almost 90% from prewar levels. Unable to get the supplies it needed to maintain its armed forces the Japanese were forced to submit to the demand for unconditional surrender. As Friedman points out, the lesson was driven home — the bulk of modern Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force is devoted to antisubmarine warfare.

For World War II’s submariners it was not a one-sided battle. While American submarines claimed 201 Japanese warships and 1013 merchant vessels (roughly 55% of all tonnage sunk), fifty four American submarines made their final dive to the floor of the Pacific, taking 3500 sailors to a watery grave. The loss rate — 22% — suffered by the Submarine Service was the highest experienced by any force of their size in the war. But the blood and iron lost in the shallows and deeps of the Pacific destroyed Japanese war making ability. It almost didn’t happen that way.

Run Silent, Run Deep

While salvage crews rescued what they could from the twisted wreckage of the Pacific Fleet in the aftermath of the raid on Pearl Harbor, the American Navy scrambled to strike back. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King turned to the only branch of the service with the ability to damage the Japanese without risking the few precious carriers — the submarine service.

Before December was out, American submarines had struck back with a ferocity born out of desperation and a grim sense of revenge. One boat alone carried out attacks on six Japanese ships putting 13 “fish” (naval slang for torpedoes) in the water. Overall there were forty-six separate attacks on Japanese shipping, both civilian and military, involving the launching of 96 torpedoes. The scope and number of operations were a tribute to the determination and hunting skills of the submariners. The one problem, from the naval warfare point of view, was that all this activity resulted in the loss of exactly five freighters. Ironically, at the same time the Atlantic German submarine commander Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz was complaining to his captains that it took them took 816 torpedoes to sink 404 ships. Something was terribly wrong in the Pacific.

Commanders, Tactics & Torpedoes

As 1941 faded into 1942, then 1943, three things became obvious: American submarines in the Pacific were commanded by unsuitable commanders utilizing inappropriate tactics and armed with useless torpedoes.

It is axiomatic that those who rise to high command in peacetime are frequently ill-equipped to handle the rigors of battle. Peacetime is a period when competency is judged on skill at personal relationships, office politics and ballroom dancing rather than aggressiveness, battle experience or drive. At the start of the war, many submarine commanders were too old, too poorly trained and unready for the tasks they faced. In one noted instance a sub captain, assigned to his first combat patrol, turned the conn over to his Executive officer and locked himself in the cabin until it returned to port. The Navy recognized the problem and conducted a house cleaning — in 1942 thirty percent of submarine captains were relieved of their commands as unfit for duty. Their places were taken by men with more fire in their bowels.

Tactics were just as poor. Prior to the war American submarine doctrine saw the submarine as a forward scout responsible for the protection of battleships. Combat tactics called for submarines to attack fully submerged using sound rather than their periscopes to attack. It was unrealistic and what was worse, completely oblivious to the lessons of World War I and the naval war to that date. German submarines, employing much more aggressive tactics were on the verge of strangling Great Britain. Before Pearl Harbor the efficiency of the German U-boats had forced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to move warships from the Pacific to the Atlantic and use American vessels to protect British convoys.

The Germans understood the purpose and strengths of submarine warfare. Submarines operate best as aggressive attackers. Like sharks they are efficient killing machines that need to hunt. The role of scout is as poor a one for a submarine as passenger plane is for an F-15.

The American Navy learned quickly. Commanders were replaced and tactics altered. But still the number of Japanese ships sunk was embarrassingly low. Through 1943 the navy expended 14,748 torpedoes against 4,112 Japanese ships — sinking 1,305. At the same time Doenitz was complaining about using two torpedoes to sink a ship, American submarines were expending 11.3 per target sunk.

Torpedo Tribulations

The third problem lies with the submarine’s main weapon — its torpedoes. To start with, there weren’t that many around. The navy had started the war with a few hundred torpedoes; nearly half of which (233) were lost when the Philippines fell and the stockpiles there abandoned. Submarine torpedo production was all of 60 per month at the beginning of 1942. Submarines went to sea with two thirds of their optimum content with orders not to waste them. Ironically, in the middle of a war, submarine commanders were praised for not expending their ammunition on the enemy. The shortage might actually have been a blessing in disguise. There were some problems with the main torpedoes.

American submarines were equipped with two types of torpedoes. The older Mark 10, and the fifteen-years-in-development, top secret Mark 14. The Mark 10 was an adequate torpedo but outdated and not particularly powerful. Only the older S-boats were outfitted with them. The navy had been replacing it with the ultra-modern Mark 14.

Mark 14 Mayhem

The Mark 14 had three separate and distinct glitches. It ran 11 feet deeper than its setting, it had a faulty magnetic detonator which caused premature detonation, and the contact detonator was incredibly fragile. Compounding matters was the attitude of the Navy. Replacing incompetent commanders was done as soon as the problem was noted. Tactics and doctrine were revised when they proved untenable. But the torpedo problem would haunt the submariners for two years before the three problems were admitted to and solved by a hidebound Navy bureaucracy.

Design of the Decade?

The major difference in the models lay in their respective methods of detonation. The Mark 10 torpedo detonation design was as straightforward as a sledge hammer — it hit its target and exploded, opening a hole in the hull at or below the waterline. The Mark 14 was designed to explode while passing under the target’s keel, thus breaking the back of the ship. The magnetic detonator was supposed to explode the device at the exact place it would do the most damage. In theory it was a great idea. The reality was different.

The Mark 14 torpedo looked as if it had been designed by Rube Goldberg in a particularly creative mood. Its 92 pound Mark 6 detonator was a complicated affair complete with chains, spinners and a compass needle. It had poor structural strength and as fragile as a glass watch. To make matters worse the Navy had never really put the Mark 14 through any testing.

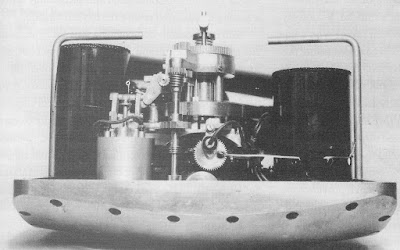

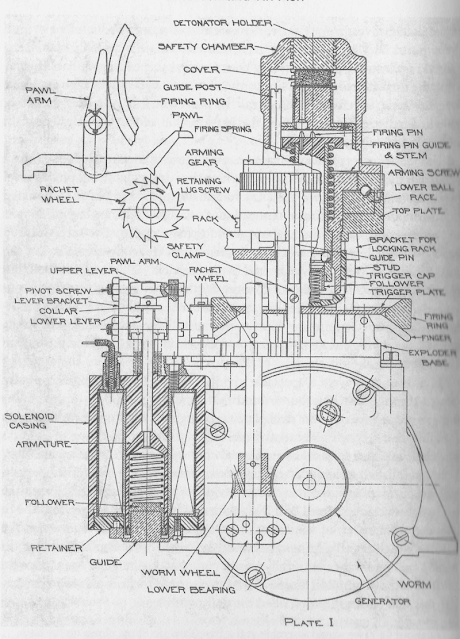

Mark VI Exploder Version 1

In the interwar years of severe budgetary restrictions cash for testing was given a low priority. The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) convinced itself that at $10,000 a piece, the Mark 14 was just too expensive to blow up during testing. So the warhead was filled with water and deliberately set to pass under the under the target to preserve both for reuse. A test firing was deemed successful if the exhaust bubbles passed under the target ship. Not a one was ever actually exploded. In the words of the Submarine Operational History: “The war began with an entire generation of submarine personnel none of whom had ever seen or heard the detonation of a submarine torpedo.”

Firing Failures

Seven days after Pearl Harbor the Navy should have recognized they had problems with their torpedoes. An American submarine found a Japanese tanker, put it in its sights and let fly one of the state of the art Mark 14 fish. The torpedo, fired from a range of 1000 yards, sped along straight and true then detonated 450 yards from the target.

The submarine commander, who had done previous service with BuOrd knew as much about the Mark 14 torpedo as anyone commanding a boat. Suspecting the problem might be the magnetic detonator he deactivated them on his Mark 14 torpedoes. Continuing his patrol he fired a total of 13 torpedoes at six different targets without a hit.

Duds

Once Nimitz’ subs stopped using the magnetic detonating feature it became obvious that most of the torpedoes were duds. One sub reported firing 15 fish at an anchored Japanese Whale Factory. Eleven torpedoes failed to explode though they hit their target. Lockwood ordered more tests, this time of the contact detonators. Mark 14s were fired at a cliff and dropped from a crane in an effort to get to the bottom of the problem.

By September the tests had proven that the Mark 14 contact firing pin was unfit for combat. The pin was so delicate that it would crush without detonating the torpedo on an optimal hit of 90 degrees relative to the target. At 45 degrees, 50% of the torpedoes failed. Lockwood ordered the submariners to target glancing shots at enemy vessels. Yes, he admitted, they were more difficult to make, but they had a chance of being successful while the problem was corrected

Totally frustrated the captain informed the Commander, Submarines, Southwest Pacific1 (COMSUBSOWESPAC) that he had disobeyed orders by disarming the magnetic detonator. Regrettably, he added, even this did not seem to help. He opined that the torpedoes were either running significantly deeper than their setting or the contact detonators were not functioning or both. Aware they had been only tested using a water filled warhead he hypothesized that the actual Torpex explosive, being significantly heavier, was carrying the torpedoes down to a lower depth. He requested that he be allowed to conduct test firings at a fish net to check the depth setting on the torpedo. His request earned him a reprimand and a visit from a BuOrd officer. This officer, after reviewing crew procedures and conducting an inspection of the ship’s remaining torpedoes, placed the blame squarely on the crew.

Still the problem continued. On April 1, 1942 USS Scuplin fired a spread of three Mark 14s at an unescorted cargo ship at 1,000 yards. The captain of the Scuplin was the only thing that exploded as he watched the torpedoes pass harmlessly under the target. By July 5th 1942 Scuplin had fired 45 torpedoes damaging all of seven ships.

Over the next months the misses mounted. USS Spearfish fired and missed with four torpedoes at a Japanese cruiser. USS Skipjack targeted two on a seaplane tender with no hits. Scuplin spent another six days missing three Japanese freighters with nine Mark 14 torpedoes.

Henry Bruton, commander of USS Greenling, fired four Mark 14 torpedoes at a Japanese freighter after a textbook approach. All of them missed. Bruton went ballistic. Ordering the sub to the surface he passed the Japanese ship, setting up for another attack at 1,350 yards. Two fish sped toward the helpless freighter in the bright moonlight. Bruton watched as they missed. Again Bruton ordered Greenling to the surface to set up for a third attack. By now the Greenling had been spotted by the target. During the ensuing battle Bruton fired two more torpedoes. One was clean miss, the other exploded — 500 yards short of the target.

In the late summer of 1942 USS Seawolf ended her sixth patrol having fired 17 Mark 14s to sink two ships. Freddy Warder, Seawolf ‘s captain then loaded his submarine with a combination of the old Mark 10 “sledgehammer simple” and the newer Mark 14 torpedoes. Finding a 8,000 ton transport at anchor with no tide or current he conducted a test. At 1,400 yards he fired 4 Mark 14 torpedoes. The first, set at 18 feet, ran under the target exploding on the beach. The second, set at eight feet, appeared to detonate on the transport’s side while the other two, set at four feet, failed to explode. Warder, with Japanese shells exploding around his periscope, withdrew, reloaded his tubes with Mark 10s and attacked again. Both ran “hot and true” and sank the transport.

Captains complained, but no one seemed to be listening. A number of senior officers had their suspicions but they ran into brick walls.

Lockwood

In June 1942, Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood became COMSUBSOWESPAC. After reading the war diaries of his submariners he became convinced that poor torpedo performance was the root cause of fleet’s poor sub kill rate. Lockwood asked BuOrd if they had recently tested the Mark 14. The answer was a curt “No.” Lockwood then purchased a 500 foot long fish net and tested the Mark 14 himself. The results were no surprise to the submarine captains. One torpedo, set at 10 feet, ran through the net at 25 feet, another with the same depth setting passed through at 18 feet. Another, set to ride on the surface, went through the net at 11 feet.

Lockwood notified BuOrd of his results and was told that no reliable conclusions could be drawn from his test. Lockwood then repeated the test with another submarine. Three torpedoes, each set at 10 feet, cut the net at 21 feet. In July, informed of Lockwood’s tests, King, ordered BuOrd to test the Mark 14. In August of 1942 the Bureau completed its tests and formally declared the Mark 14 ran 11 feet deeper than set.

Premature Explosions

Even after this problem was “solved” complaints on torpedo performance continued. Most concerned the issue of premature explosions. Lockwood endorsed these reports and sent them to Washington. Rear Admiral Ralph Waldo Christie, the BuOrd officer largely responsible for the development of the Mark 14 and Mark 6 magnetic detonator, then entered the fray.

When the failure of the attack was blamed on his beloved detonators and torpedoes. Christie wrote Lockwood: “It is not defective torpedoes nor exploders causing the dearth of sunken Japanese ships. It is ineffective submarine crews… and by the way stop your negative reports about the torpedoes.” Lockwood replied, “From the amount of belly-aching it (Lockwood’s note) contains, I assume that your breakfast coffee was scorched or perhaps it was a bad egg. You boys may figure the problem out to suit your favorite theories but the fact remains that we have now lost six valuable targets due to prematures so close to that the skipper thought they were hits.”

Lockwood made his feelings plain at a conference in Washington DC. He ripped into the BuOrd declaring “If the Bureau of Ordnance can’t provide us with torpedoes that will hit and explode, then for God’s sake get the Bureau of Ships to design a boat hook with which we can rip plates off a target’s sides.”

Lockwood was immediately confronted by an old friend, Rear Admiral WHP “Spike” Blandy, the BuOrd Chief. “I don’t know whether it’s part of your mission to discredit the Bureau of Ordnance, but you seem to be doing a pretty good job of it.”

“Well, Spike,” Lockwood retorted, “if anything I have said will get the bureau off its duff and get some action, I will feel that my trip has not been wasted.”

Christie Checks

In early 1943 the submarine command structure changed. Lockwood moved from being COMSUBSOWESPAC to COMSUBPAC at Pearl Harbor under Admiral Chester Nimitz, the Commander In Chief, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC). Christie was named COMSUBSOWESPAC. Far from bowing to the obvious, Christie conducted a vendetta against skippers who slurred his torpedo. When two of his captains questioned the reliability of the Mark 14 they were transferred out. Word spread that to question the Mark 14 in Christie’s command was a sure way of being assigned shore duty.

To forestall criticism, Christie actually went on patrol with his most successful captain in order to observe the Mark 14 in action. Of three fired in the first attack, the first torpedo broke to the surface zigzagged and passed in front of the target while the other two hit and sank the ship. During the second attack on this cruise Christie watched as 18 torpedoes were fired at one ship. Only five hit but none of the blows was a killing one and the Japanese ship steamed off. Christie deemed the operation a success.

Nimitz Takes Action

The missed opportunities continued to mount. In April 1943 the USS Tunny had worked herself into the center of a Japanese carrier formation near Truk. On one side loomed a fleet carrier, on the other two smaller ones. Tunny launched four aft torpedoes at the small carrier and six at the big one at a range of 850 yards. Despite the spread and position only one of the small carriers was damaged while most of the other torpedoes detonated prematurely. Tunny had to flee for her life with little to show for her efforts.

On June 11, 1943 US submarines entered Tokyo Harbor, one of the war’s most daring feats. Salvo after salvo failed to sink any fleet units in the harbor’s confined spaces.

This and other failed attacks were enough for Nimitz. In June 1943, CINCPAC ordered the deactivation of the magnetic warheads on his submarines. Christie, still maintaining his faith in the magnetic detonator, continued their use in his fleet.

A Matter of Physics

Nimitz was right, Christie was wrong. The magnetic detonator on the Mark 6 was not working. After much investigation, it turned out to be a matter of physics. Every steel bottomed ship was encased in a magnetic field that radiated in all directions. Designers presumed that this field extended an equal distance in all directions, forming a perfect hemisphere under the bottom of the ship. But there was flaw in the reasoning. What was not understood (by anyone in the world) was that the magnetic field encasing a ship varied in shape depending in circumstances. Near the equator, this magnetic envelope flattened out until it resembled a thick disk more than a hemisphere. Since the torpedo would enter the magnetic field some distance from the ship it would explode harmlessly.

Drawing of the Mark VI Trigger operation.

The war was now eighteen months old. The Navy had already discovered that its state of the art torpedo was running eleven feet lower than its setting and that the magnetic detonator wasn’t working. What else could go wrong?

In November 1943 Christie was given a direct order by Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, Commander of the Seventh Fleet to disarm all the magnetic detonators. It was a bitter blow and he refused to accept its logic. “Today,” he wrote in his diary, “the long hard battle on the Mark 6 magnetic feature ends with defeat. I am forced to inactivate all magnetic exploders. We are licked.”

During the same month a fix for the contact pin problem was introduced. Now when the submarines pulled out of port they were finally able to hunt and kill, not shoot fizzling fish.