Category: War

By the time Israel’s advanced F-35 jet fighters swooped in to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities and military leadership, a lower-tech threat had already crossed the border and was in position to clear the way.

Israel had spent months smuggling in parts for hundreds of quadcopter drones rigged with explosives—in suitcases, trucks and shipping containers—as well as munitions that could be fired from unmanned platforms, people familiar with the operation said.

Small teams armed with the equipment set up near Iran’s air-defense emplacements and missile launch sites, the people said. When Israel’s attack began, some of the teams took out air defenses, while others hit missile launchers as they rolled out of their shelters and set up to fire, one of the people said.

The operation helps explain the limited nature of Iran’s response thus far to Israel’s attacks. It also offers further evidence of how off-the-shelf technology is changing the battlefield and creating dangerous new security challenges for governments.

The exploit came just weeks after Ukraine deployed similar tactics, using drones smuggled into Russia in the roofs of shipping containers to attack dozens of warplanes used by Moscow to attack Ukrainian cities. The intelligence operations showed how attackers are using creativity and low-cost drones to get past sophisticated air-defense systems to destroy valuable targets in ways that are hard to stop.

The operation by Israel’s spy agency, Mossad, was aimed at taking out threats to Israeli warplanes and knocking out missiles before they could be fired at cities. The teams on the ground hit dozens of missiles before they could be launched in the early hours of the attack, one of the people said. Israel’s air force also focused heavily on air defense and missiles in the first days of the campaign.

Iran ultimately fired around 200 missiles at Israel in four salvos Friday and overnight into Saturday, leaving three dead and property damaged around Tel Aviv. Israel had expected a much more severe response, said Sima Shine, a former senior intelligence officer in the Mossad and now head of the Iran program at the Institute for National Security Studies, a think tank in Tel Aviv.

Iran, however, has vast resources it could muster for more severe attacks.

“We expected much more,” Shine said. “But that doesn’t mean we won’t have much more today or tomorrow.”

The attacks on Iranian air defenses were more decisive, helping Israel quickly establish dominance in the air, she said. Israel’s air force has also aggressively targeted those defenses.

Israeli military spokesperson Effie Defrin said Saturday that Israel overnight had attacked targets in Tehran with 70 fighter planes that spent more than two hours in the Iranian capital’s airspace.

“This is the deepest distance that we have operated so far in Iran,” Defrin said. “We created aerial freedom of action.”

An advisory from Iran’s intelligence services circulating Saturday in some of the country’s newspapers, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-linked publication Tasnim, told people to be on watch for Israeli use of pickups and cargo trucks to launch drones.

Israel has deeply integrated ambitious intelligence operations into its warfighting. It kicked off a two-month campaign against the Lebanese militia Hezbollah last fall with an operation that caused thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies carried by its ranks to suddenly explode.

The country has also shown that its agents have deeply infiltrated Iran. Last summer, Israel killed Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh by sneaking a bomb into his heavily guarded room at a Revolutionary Guard guesthouse and detonating it when Haniyeh attended the inauguration of Iran’s new president.

In the current campaign, the Mossad’s operations inside Iran have included hunting for leadership targets in Tehran, one of the people familiar with the operations said.

Drones have been a regular feature of Israel’s operations in Iran. In 2022, it used explosive-laden quadcopters to strike an Iranian drone-production site in the western city of Kermanshah. A year later, it used drones to target an ammunition factory in Isfahan.

The spy agency began preparing for the current drone operation years ago, the people said. It knew where Iran kept missiles to be ready for launch but needed to be in a position to attack them given the country’s size and distance from Israel.

Mossad brought the quadcopters in through commercial channels using often unwitting business partners. Agents on the ground would collect the munitions and distribute them to the teams. Israel trained the team leaders in third countries, and they in turn trained the teams.

The teams watched as Iran rolled out missiles, then hit them before they could be erected for launch, the person said. Mossad knew the trucks that move the missiles from storage to the launch site were a bottleneck for Iran, which had four times as many missiles as trucks.

The teams took out dozens of trucks, one of the people said. They were still operating on the ground deep into Friday.

The operations—and making them public—have an important ancillary effect, said Shine, the former head of the Mossad’s Iran desk.

“No one in Iran in the high echelons can be sure he isn’t known to Israeli intelligence and won’t be the target,” she said. “It’s not just the damage caused but the nervousness it brings.”

This week I got a nice email from a hospital that happened to be near my house, and the guy was basically like, “hey, shit is pretty bad right now, we need an inspirational story about a badass last stand against impossible odds.”

Now, sure, I’ve got plenty of those, but with everything going down right now and you guys basically risking your lives every day to serve as the only line of defense against the impending collapse of global society, I figured it was the least I could do to sit here in my nice chill quarantine drinking a beer in my pajamas at eight AM on a Friday and hammering out the story of what I believe to be the most badass last stand I haven’t yet featured on the site.

Truly an heroic move on my part, I know, but let’s hold off on the parade until after we’ve survived the post-apocalypse.

Everyone by know should be at least rudimentarily familiar with the story of Pearl Harbor (I mean, they did make a Michael Bay movie about it), but while the Japanese were whipping torpedoes at US battleships in the Pacific.

They were also storming across Southeast Asian sneak-attacking the balls off the Brits and Commonwealth forces as well – within a few months of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked and captured Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Burma (present-day Myanmar), and Papua New Guinea, and they even sent bombers and Zeroes on strafing runs of bases along the Australian coast.

The last thing the Brits expected to come running out of the jungles of Vietnam were a bunch of super pissed dudes with samurai swords slashing the faces off of anything that didn’t realize how awesome the Emperor was, and for the next several weeks the Commonwealth forces fought a desperate rear-guard action during a brutal thousand-mile fighting withdrawal back to British-controlled India.

But the Japanese weren’t done stomping ass just yet – they had much bigger aspirations. They were going to take India from the English.

The reasoning here is legit – they were like, hey, the English have been colonial oppressors of the Indian subcontinent for a couple centuries at this point, and there was a big growing movement throughout the country for Indian independence.

So, with the last remnants of the British Southeast Asia Command digging in along the border, all Japan needed to do was to smash these guys’ balls, seize a big victory, and spear into India, and the Indian people would rise up and turn on the Brits, throwing them out of Asia for good.

I mean, who knows if this would have worked (I can’t really envision Gandhi being happy with trading British dominion for Japanese Emperor-worship), but my general feel of things is that the Japanese weren’t super warm and fuzzy to the nations they conquered and my guess is that the people of India would rather have played cricket while drinking afternoon tea than had their heads chopped off by katanas, so there’s that.

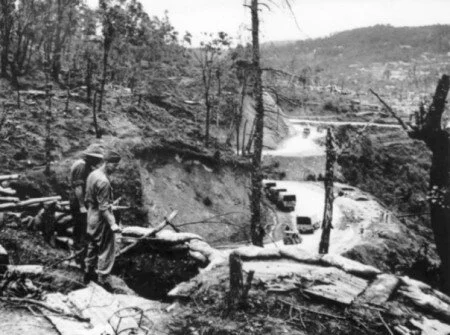

Surveying defenses at Kohima.

The British line was anchored on a city called Imphal, which was easily resupplied by an airstrip a few miles deeper into India that served as a landing zone for resupply flights coming over the Himalayas from China.

The road that connected the depot to the city was one of those windy terrifying death trails that twisted and turned along switchbacks through miles of super-dense jungle – one of those things where you have to charter a tour bus to drive through it and you spend the entire trip convinced that your janky-ass 1980s Isuzu is going to roll off a cliff face at any moment and send everyone careening to a fiery death hundreds of feet below.

The road was anchored at a small town called Kohima, which was garrisoned by a tiny group of Commonwealth troops, most of them admins, supply, and logistics guys who did their best work with a socket wrench or a ball-point pen and hadn’t picked up a rifle since basic training.

There was also a small hospital there, where sick and wounded men could recover, but basically this tiny little hilltop town was just a glorified truck stop along the road from the supply depot to the front lines at Imphal.

It was tiny, in the middle of thick jungle, and there was NO WAY ANYTHING BAD WOULD HAPPEN HERE GUYS if you haven’t seen where I’m going with this yet, so, naturally, when it came time to build up defenses against the impending onslaught of hundreds of thousands of badass Japanese soldiers, the British concentrated on fortifying Imphal and didn’t bother reinforcing positions at Kohima.

Then they received intel that Japanese forces were somehow traversing the impenetrable jungle on a sweeping maneuver towards Imphal, and that the men of the General Sato’s 31st Division had not only managed to storm 160 miles through ultra-dense jungle in just two weeks, but that they’d also somehow dragged a bunch of big-ass artillery pieces with them, and now they were poised to strike Kohima and cut off the only road connecting Imphal to its resupply lines.

All that stood in their way was a small group of British, Indian, and Nepalese soldiers under the command of Colonel Hugh Richards.

Bren gun teams digging in.

Colonel Richards arrived in Kohima on March 22, 1944 – exactly 77 years ago this weekend. Richards was a 50 year-old career soldier who had joined up with the Worcestershire Regiment decades ago, served as the XO of the West Yorkshires for three years, and had recently been commanding the 3rd West African (a unit of Chindits who were doing badass jungle warfare commando shit deep behind enemy lines).

But got kicked out when his commander found out that Richards had lied about his age and was actually 10 years older than the max age for that unit. Which is pretty badass, honestly.

When Richards arrived, he assessed his situation, and it didn’t look good. He had 2,500 troops at his command, but only about 1500 of them had been trained in Infantry… and they were facing an estimated force of 15,000 battle-hardened, veteran soldiers from the Japanese 31st Division.

Outnumbered ten to one, with less than a week to prepare his defenses, Richards’ job got even more difficult because he was only the military commander and didn’t have command over the administration of Kohima – meaning that his would-be defenders were being cycled in and out of the supply depot without his approval or knowledge, and, in his words, “the size of the Box, the number of troops available to hold it, and the facilities required were therefore almost impossible to compute”.

He had no barbed wire, very little water, minimal medical supplies, and just a week to dig in to a fortified position at a place he’d only just visited that morning and then defend it against an entire Division of war-forged veterans.

When the word finally came on March 29th that the Japanese had cut off all roads to Kohima and surrounded the city, Col. Richards had at his command about 1500 guys – 446 men from the 4th Battalion of the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment, 260 veterans from the Assam Rifles (most of them wounded and exhausted from weeks of fighting), a detachment of soldiers from the 161st Indian Brigade, an Indian mountain artillery battery, and two companies of Gurkhas, all tasked with defending 36 square miles of ground against six damn battalions of Japanese infantry with full artillery support for an unknown amount of time, with minimal possibility of resupply or reinforcement.

These pamphlets were air-dropped to the defenders at Kohima by the Japanese.

The first attack came at dusk. Supported by thundering artillery and mortar fire from unseen positions deep in the jungle, the men of the 31st Division charged forward from the jungle, firing and screaming towards the hastily-constructed defenses.

The men of the West Kents and the 161st Brigade, had orders to wait until the enemy was 30 meters out before opening up, thumping the Bren guns and Enfields into the jungle in a desperate attempt to slow this massive onslaught.

Fire poured into the Japanese lines, yet on they came, rushing and diving into British trenches and devolving the combat into brutal fighting with fists, knives, swords, and shovels. From his command post, Colonel Richards did his best to coordinate his defenses, aided in no small part by a team of Sikh linesmen who spent most of the battle running into artillery fire to repair damaged radio wires, but the situation was grim from the very beginning – at one point, Richards had to reinforce a collapsing flank by sending out an assault team consisting of seventeen mule drivers and a handful of admins because that was all he could commit to a counter-attack.

The fighting was brutal – as one historian put it, “nowhere in World War II—even on the Eastern Front—did the combatants fight with more mindless savagery” – but when dawn arose, the Brits had held the line.

Now they just had to hold out for 17 more nights of basically the exact same thing, and do it without any additional food, water, medical supplies, or ammunition.

Combat raged for weeks in much the same way. During the day, the Japanese would shell the beleaguered defenders relentlessly with huge-caliber explosive shells that rocked the earth and blasted away defenses, and at night the Japanese Banzai wave attacks would surge out of the jungle and tracer fire would chew up earth and people on both sides.

British guns from the Indian Mountain Artillery would be called in at danger close ranges, sometimes hitting targets less than 30 meters from the Commonwealth front lines, then reposition before dawn so they wouldn’t be easy targets for the bigger Japanese guns.

Over the ensuing hours and days the British box began collapsing, as the Commonwealth troops suffered severe losses and slowly consolidated their positions back towards the Governor’s Mansion atop the 5,000-foot-tall hill in the center of Kohima.

The Japanese surged on, fighting uphill through murderous fields of bullets, until at one point both the West Kents and the 31st Division were dug into trenches on opposite sides of the Governor’s tennis court – in lines so close to one another that you could literally chuck a grenade from your trench into the enemy trenches.

One Brit later wrote that “it was the nearest approach to a snowball fight that could have been imagined,” which sounds kind of cute and funny until you realize that each snowball in this metaphor is a damn frag grenade packed with half a pound of TNT and capable of blowing your leg off from a couple meters away.

Sure.

The heroes of this battle are legion, but as the commanding officer it was Colonel Richards’ job to deploy his troops in the defense and keep up their morale, so during the entire length of the battle he would make personal daily tours of the battlefield every morning – and, in true British Officer fashion, he would Kilgore it and just walk around all calm and confident even though artillery shells were blowing up mere meters from him and sniper fire was whizzing over everyone’s head pretty much constantly.

He was, according to his men, “a good British officer, walking about, looking unafraid… [he was] under strain, but understanding, considerate, never rattled, often laughing and joking under fire,” and when they saw him his troops would call out to him, “Come on sir, you’re winning!’.

But as the battle dragged on, things got way worse and the enemy became more ferocious and desperate. The Japanese had made their incredible march through the jungle primary by ditching their baggage train and most of their gear in exchange for speed, with the hopes that they’d be able to crush this force 1/10th their size and steal all the good shit stashed at Kohima, but as the defenders held out the Japanese got lower and lower on critical things like food and ammunition.

And, for the defenders, without any sign of reinforcement on the way, they were down to rations of a half-cup of water per man per day, which is like not enough for a regular person who is sitting around being a fat bastard in quarantine and certainly isn’t enough for a dude who is pulling a trigger, reloading, lobbing grenades and running around for eighteen hours a day.

On the Japanese came, charging with rifle butts, samurai swords, and anything else they could manage. The British lines continued to collapse, the enemy getting so close now that men in the medical tents were getting shot to death while they were being operated on.

Nearly every British soldier had been wounded, and those too messed-up to continue fighting simply laid in a stretcher in the tent, with their rifles by their side and a single .303 round in the chamber to ensure they wouldn’t become prisoners of an enemy that was notoriously not great about the treatment of their POWs.

On the “Black Thirteenth,” April 13, the hope of these heroic defenders was crushed when a British air supply run of C-47s missed the (admittedly incredibly tiny) drop zone and parachuted crates of artillery shells, white phosphorous, food, grenades, and bullets directly into enemy lines. The Japanese taunted the Brits with it, loaded it into some artillery pieces they’d captured, and planted a HE shell directly into the British Medical Tent, killing dozens of doctors, medics, and patients.

Colonel Hugh Richards, who by now was fighting on the front lines with an Enfield in his hands, radioed British HQ. He said that Kohima had two more days, maximum, but that they were going to fight this battle “to the last man, with the last round.”

It would be five days before British troops would break through the siege to reinforce Kohima.

Surveying the bombed-out hillside of Kohima.

On the morning of April 18th, 1944, Hawker Hurricane fighter-bombers screamed in above the treetops dropping ordinance onto enemy positions and the first tanks and infantry of the Commonwealth First Punjabi Regiment marched up the road to Kohima.

When they arrived, they found Colonel Richards and the battered survivors of Kohima huddled into a defensive perimeter just 3700 square feet wide – about the size of a really nice house. They hadn’t slept in days, and were starving, exhausted, and out of ammunition… as one observer put it, “they looked like aged, bloodstained scarecrows, dropping with fatigue; the only clean thing about them was their weapons, and they smelt of blood, sweat and death.”

During the ferocious battle the night before, the Japanese had broken through the final lines of defense, and ferocious hand-hand-combat had raged through the rooms of the Governor’s Mansion and the surrounding buildings as the West Kents, Indians, Gurkhas, and Japanese locked blades in brutal sword and knife-fights.

The Battle of Kohima would go on for another month and a half, with plenty of back-and-forth along the way, but Colonel Richards, the Assam Rifles, the West Kents, the Mountain Battery and the rest of the heroic defenders of Kohima had held the line and broken the wave of the Japanese onslaught through Southeast Asia.

In a battle that went on concurrently with the D-Day invasion of Normandy and got lost a bit in the shuffle of that massive encounter, the heroes of the Commonwealth had won a huge victory and begun a turning point that would push the Japanese back out of Burma, Southeast Asia, and southern China and break their power in Asia for good.

It was the turning point of the war for Asia, fought over a tennis court by desperate, starving heroes, and one of the most decisive and important moments of World War II.

This memorial stands on the battlefield of Kohima, where Colonel Hugh Richards and his men held the line against impossible odds.

(He left the British Army as Brigadier Hugh Richards, CBE, DSO

This youthful rascal was the most successful fighter pilot of all time. He was around 21 years old in this picture.

This youthful rascal was the most successful fighter pilot of all time. He was around 21 years old in this picture.Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

The famed Luftwaffe pilot Major Erich Hartmann was the most successful fighter ace ever, but he had a rocky start. He accidentally taxied a Ju-87 Stuka through a building after a ferry flight before he even saw action. On his first combat mission, Hartmann got fixated and ran his plane out of fuel without hitting an enemy aircraft. He ultimately crash-landed sixteen times. However, by the end of World War 2, he had flown 1,404 combat missions and had been credited with an astounding 352 aerial victories. Seven of his kills were American, while the rest were Russian—all at the controls of the Messerschmitt Bf-109. His tally will never be bested.

Table of contents

Prestigious Pilots

Hartmann shot down his 352d Allied plane mere hours before the war ended. He surrendered to American forces only to be handed over to the Soviets. They were none too grateful for his having shot down some 345 Russian aircraft. He served a decade in a communist gulag before returning to West Germany where he joined the West German Air Force. Hartmann was forcibly retired in 1970 over his opposition to the West German purchase of F-104 Starfighters, which he deemed unsafe. He spent his twilight years as a flight instructor. As a pilot myself I would dearly love to have his signature in my logbook.

By contrast, the leading American ace, Major Richard Bong, had 40 aerial victories. In both cases, these two men were treated like rock stars by their respective governments. Hartmann was awarded the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds. At the time this was the most prestigious combat decoration offered by the German military.

Major Bong earned the Medal of Honor. Both of these extraordinary aviators were extensively exploited by the media of the day to drum up support for their respective war efforts. So why the massive disparity in kill counts between these two esteemed pilots? That all comes down to national policy and priorities.

Destined to Fly

German aces flew until they died. Aside from the occasional leave, Hartmann flew combat constantly from October 1942 through the end of the war. By contrast, American policy was to rotate successful aces back to the States to sell war bonds and train new generations of pilots. This practice, combined with a seemingly infinite supply of top-quality warplanes, is what helped the Allies win the air war.

Both men later claimed that they were not great shots. Their preferred technique was to approach a target aircraft unawares and engage from close range out of an ambush position. While this seems neither chivalrous nor glamorous, war never is either of those things. The mission was to kill the enemy, and Bong and Hartmann were masters at it.

Before The Croc He Lived in Wisconsin

Richard Bong was born in Superior, Wisconsin, in September of 1920. He went by Dick. He was a compulsive model builder in his youth and played clarinet in his school band. In 1938 Bong enrolled in the Civilian Pilot Training Program and earned his wings. In May of 1941, he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet Program. One of his flight instructors was Captain Barry Goldwater who went on to become a US Senator of some renown.

Bong eventually trained to fly the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. The Lightning was, in my opinion at least, the coolest-looking airplane ever to take to the skies. While training in California he was grounded for allegedly looping his twin-engine fighter around the Golden Gate Bridge and buzzing a woman low enough to blow the laundry off her clothesline. Because of this grounding, he missed his squadron’s combat deployment to Europe. As a result, he fell in on the 84th Fighter Squadron of the 78th Fighter Group and deployed to the Pacific theater.

P-38s were in short supply in 1942, so Bong claimed his first two kills at the controls of a P-40 Warhawk. However, by January of 1943 American industry was getting advanced aircraft to the combat zones in quantity. On 26 July 1943, Bong downed four enemy aircraft in a single day flying a Lightning. The young man was on a roll.

Quickly Improving

Dick Bong racked up an impressive record, besting Eddie Rickenbacker’s WW1 score of 26 in April of 1944. Shortly afterwards he returned to the States to sell war bonds and tour fighter training schools. When he returned to the Pacific in September he was assigned to V Fighter Command staff, nominally as a gunnery instructor. In this capacity, his job was simply to hunt Japanese aircraft.

As previously mentioned, Bong often disparaged his own marksmanship. However, one day while flying cover over an aircrew rescue mission he did some remarkably rarefied shooting. It was simply that, in this case, his quarry was not a Japanese warplane.

That Others Might Live…

The area of operations this day was Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea occupies the eastern half of New Guinea and represents some of the most forbidding terrain on earth. Mangrove swamps and impenetrable jungles were rife with both malarial mosquitoes and, no kidding, cannibals. It was a particularly sucky place to get shot down.

On the day in question, one of Bong’s fellow aviators had gone down in some particularly nasty jungle. Combat Search and Rescue was not the rarefied art that it is today, so any rescue efforts would be left up to Bong’s squadron. Once they had established the approximate location where this man had gone down, three of Bong’s squadron mates struck out in a tiny boat across an expansive lake in search of him. Bong orbited above to ensure that no Japanese fighter planes crashed the party.

…In A Deadly Place

Papua New Guinea is home to scads of stuff that can kill you. The New Guinea crocodile tops out at around 11 feet and typically keeps to itself. However, the legendary saltwater crocodile that is indigenous to the same area is a freaking monster. I saw these things in Australia back when I deployed there as a soldier in the 1990s, and they were positively prehistoric. Saltwater crocs enjoy a notoriously grouchy disposition and can reach lengths of 21 feet or more.

As Bong’s three mates made their way across this expansive lake in their tiny little boat, the eagle-eyed fighter pilot noted a disturbance in the water behind their craft. Swooping in for a closer look, Bong noted one of these leviathan crocodiles rapidly gaining on the boat. He had no means of communication with the hapless pilots, all three of whom were almost assuredly not aware of the threat steadily approaching from the stern. As such, Bong did what any decent fighter pilot might have done. He armed his guns.

The Airplane That Hit A Crocodile

The P-38 was unique among the pantheon of WW2 fighter aircraft in that it had a combination of four AN/M-2 .50-caliber machineguns along with a single 20mm cannon Hispano M2(C) 20mm cannon all clustered tightly in the nose. Each fifty packed 500 rounds, while the 20mm had 150. More conventional American combat aircraft like the P-40 Warhawk, the P-51 Mustang, and the F4U Corsair sported half a dozen AN/M-2 guns. The fact that those of the Lightning were collocated in the nose offered a greater density of fire and subsequent accuracy potential than aircraft with wing guns that had to be zeroed to converge at a fixed point in the distance.

However, the 20mm produced a lower muzzle velocity than the fifties and subsequently offered disparate ballistics as a result. In a running dogfight that’s not that big a deal. When you’re trying to keep your buddies from being eaten by a crocodile, however, it becomes fairly critical.

Just a Quick Burst of Bullets

Bong deactivated his fifties and left his 20mm hot. Slowing his speed to something comfortable he judged the geometry of the engagement and set up his attack run. By now the enormous predator was getting close to his pals. Pulling back his throttles until the big fighter was in a shallow glide, Bong aligned his glowing reticle with the huge reptile and squeezed off a burst.

A 20-foot crocodile is one of the most formidable predators in the natural world. However, its tough leathery hide is no match for half a dozen 20mm high explosive rounds. Bong blew the beast to pieces without harming his terrified buddies. Dick Bong famously adorned the side of his fighter plane with the smiling visage of his fiancée, Marjorie Vattendahl. Though his plane eventually sported 40 separate Japanese flags representing the enemy aircraft he had downed in combat, there was no indication that Bong ever added the crocodile to his official score.

The Rest of the Story

As the nation’s top-scoring fighter ace, Major Bong was considered a national asset too valuable to risk further in combat. Bong was therefore sent home for good in January of 1945. After marrying Marge and taking a little well-deserved break, Bong assumed duties as a test pilot on the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, one of the first American combat jets.

Right to the End

On 6 August 1945, Bong took off in a P-80 to perform an acceptance test flight. It was his 12th hop in the type. The Shooting Star’s fuel pump failed on takeoff, and the plane settled toward a small field at Oxnard Street and Satsuma Avenue in North Hollywood. Bong ejected from the stricken plane, but he was too low for his parachute to open. He died the same day we dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Newspapers from coast to coast gave both events comparable billing. Major Richard Bong – fighter pilot, national hero, and crocodile hunter – was indeed a proper legend.