Category: The Green Machine

I myself do not have a very high opinion of him. So I guess that one day I will have to explain that one. But not today as I am just too tired! Grumpy

On paper, the 6.8×51 cartridge promised better armor-penetration and range than 5.56. In the real world, the original M7 Spear carbine came off as heavy, gassy, and hard to control for the average soldier.

What SIG brought out for this recent range session is what the original gun probably should have been from the beginning: an 11-inch, trimmed-down variant that feels a lot more like a fighting rifle and less like a science project.

Garand Thumb and his crew spent time on the range with what they’re calling the M7A1, a prototype the Army hasn’t officially named yet, but clearly represents the next evolution of the program.

From M7 Spear to “M7A1” – What Changed

Side by side with the earlier M7 Spear, the changes are obvious even before you shoot it.

Barrel and profile

- Original M7 Spear barrel length was around 13 inches

- The new variant runs an 11-inch barrel

- Barrel profile has been redesigned specifically around 6.8×51’s high pressures.

The 6.8×51 hybrid case runs around 80,000 psi. The original gun used a fairly overbuilt profile to survive that pressure and unknowns in the early testing cycle.

With more data, SIG has moved to a refined profile that keeps life in the same ballpark while dropping weight. Barrel life is still roughly around the 10,000-round mark for military 277 ammo, which is about what you’d expect at those pressures.

Upper receiver and weight

The upper itself went on a diet. SIG shaved roughly a pound off the system by combining the lighter barrel and trimmed upper.

More important than the raw number is where the weight disappeared from. With mass pulled off the front half of the rifle, the M7A1 feels noticeably handier than the original Spear. It mounts faster, transitions easier, and doesn’t feel like you’re steering a fence post through a doorway.

Handguard and lockup

The handguard is new as well

- More functional M-LOK real estate

- Easier access to the gas adjustment

- Beefed-up attachment with larger screws and improved clamping

Early Spears had visible barrel and rail flex under pressure at the front of the gun. The new lockup stiffens that interface. Pushing on the rail now produces far less visible deflection, and it returns to zero better than previous versions. For a gun that’s going to wear lasers and be used for night work, that matters.

Gas plug and suppressor

The gas plug has been redesigned and is easier to actuate thanks to the new handguard. The suppressor is entirely different in concept from what most shooters are used to on 5.56 guns.

- Flow-through design

- Prioritizes flash reduction and gas management, not sound

- Built to reduce gas to the shooter’s face and long-term health risk

The point here is simple: this is a frontline combat rifle, not a clandestine gun. The designers cared more about flash signature and keeping troops from sucking carcinogenic gas all day than squeezing out a few more decibels of suppression.

You still get flash, and the can heats up fast because 277 burns a lot more powder than 5.56. There’s no way around that. The heat shield helps with handling, but you still do not want that can touching bare skin or clothing.

6.8×51 Out of an 11-Inch Barrel – The Numbers

The big question with cutting the barrel down from 13 to 11 inches is whether you cripple the cartridge.

Garand Thumb ran reduced-range training ammunition through a chrono from the 11-inch barrel. That ammo is designed to limit downrange danger, but it’s loaded to give the same velocity and recoil profile as the full-range combat load.

The five-shot string averaged about 2,943 feet per second with a 113-grain projectile and a standard deviation of around 14 fps.

Put that in context

- A 20-inch M16 with 55-grain 5.56 is usually around 3,100 fps

- This 11-inch 6.8×51 is pushing more than double the bullet weight only about 150 fps slower

That is serious energy out of a very short package. Even with reduced-range ammo, drop at distance was minimal enough that the shooter could see how flat the round flies. With ball ammo, the performance only gets more unforgiving for whatever is on the receiving end.

The tradeoff is barrel wear. High pressure and high velocity eat steel. Nobody should be shocked that you are not getting 30,000 rounds out of a barrel at 80k psi.

Recoil and Controllability – Better Than the Original Spear

Compared to the original M7 Spear, the M7A1 feels like a different gun on the shoulder.

On full auto, both experienced shooters and the camera crew ran mags at CQB distances and kept rounds in the A-zone. The key points

- Noticeably more controllable than early M7 examples

- Recoil impulse feels softer and more linear

- Still more recoil than an M4, but not unmanageable

The lighter front end and tuned gas system help here. The original Spear, especially with early ammo, had shooters climbing all over the target in bursts. The new gun stays much flatter, assuming the shooter does their part and drives the gun aggressively.

Gas blowback is higher than a suppressed 5.56, as expected, but not in the “unshootable” range. Right-handed shooters will tolerate it fine. Left-handed shooters are going to get more gas thanks to where the ejection port lives and the volume of powder being burned. That is not unique to this rifle.

Controls and Ergonomics – Familiar, with Some Army Nonsense

Ambidextrous controls

- Ambi safety that can be run with the firing hand thumb

- Bolt release on both sides

- Ambi magazine release

The safety, in particular, is a real improvement over older service rifles. It feels like a proper modern carbine control layout.

Dual charging handles

Then there’s the charging setup.

The Army required both a traditional rear charging handle and a side-charging handle. That adds complexity and a little weight. It also introduces some quirks.

- If the bolt is locked to the rear and the side charger is still pulled back, dropping the bolt can smash your thumb

- You now have two systems to teach, two ways for troops to half-learn instead of one way to master

There are niche cases where a side charger helps, especially in deep prone with a ruck or barricade in the way. Whether that justifies the cost and complexity is another question. That’s not on SIG that’s on the requirement writers.

Stock and rear end

Soldier feedback killed the folding stock. The M7A1 runs a fixed stock on a 1913 rail rear end using a compact Magpul stock.

- Simpler

- Less to break

- Still allows different 1913 stocks to be mounted if needed

Sling mounting is straightforward QD at the rear and various points along the handguard. No nonsense there.

Magazines, Ammunition Load, and Squad-Level Reality

The rifle uses NGSW-pattern magazines made by SIG. These are designed around the specific feed angle needed for the steel-tipped armor-defeating projectiles in the service load. That’s the same reason you saw Enhanced Performance Magazines for M855A1 in 5.56.

A key point from the Rangers who have worked with the Spear in testing the ammo load penalty is real.

- A squad equipped entirely with 6.8×51 carries roughly 60 percent of the round count they would with 5.56

- Every magazine is heavier

- Belt-fed guns and DMRs add even more weight on top of that

That matters for fire superiority. Thirty rounds of low-recoiling 5.56 that troops can shoot quickly and accurately still count for a lot in any fight.

This is where the role of the M7A1 starts to make more sense. Several experienced voices in the video argue that this should not outright replace the M4. Instead, it makes more sense as a special weapon in the platoon.

Think of it more like

- A heavy hitter for punching through armor and light cover

- A gun for the guy anchoring a sector at distance

- A weapon for specific roles rather than a one-for-one replacement for every rifleman

That aligns with where a lot of people already assumed the program would end up even if the official messaging hasn’t fully caught up.

Armor and Near-Peer Threats

The idea behind 6.8×51 and the M7 is to keep the U.S. infantry rifle ahead of that curve.

- Higher velocity

- Harder projectiles

- Better performance through modern armor and intermediate barriers

At the same time, armor is a moving target. Plates get better every year. Coverage can increase. There is also the simple fact that armor does not cover the entire body. Bursts of 5.56 into the pelvis, lower abdomen, and thighs still ruin people in a hurry.

- Designed for a fight that may or may not happen

- Tuned for near-peer engagements at distance

- Overkill for many of the low-intensity fights the U.S. has actually been in for the last two decades.

That doesn’t make it a bad weapon. It just means everyone needs to be honest about the tradeoffs. You gain reach and armor defeat. You lose ammo capacity and some of the effortless controllability of 5.56.

Where the M7A1 Actually Fits

After several hundred rounds in the video, the verdict is pretty straightforward: the M7A1 is a clear improvement over the original M7 Spear.

Strengths

- Real battle rifle energy from an 11-inch barrel

- Better weight balance and about a pound lighter than the earlier gun

- Much improved controllability in both semi and full auto

- Stiffer handguard and better barrel lockup for laser-equipped guns

- Optics and controls that feel familiar to anyone raised on the AR platform

Weak points and open questions

- Ammunition load and weight remain a major concern at the squad level

- Barrel life and logistics at 80k psi are going to demand careful management

- Dual charging handle requirement adds complexity for marginal gain

- Left-handed shooters will still get a face full of gas compared to 5.56 guns

- This is not the right rifle for every soldier in every mission

We are watching the U.S. try to leap ahead of the armor curve with a high-pressure hybrid cartridge and a new generation of carbines built around it. The first version of that rifle had real problems. The M7A1 shows that SIG and the Army are actually listening to user feedback and iterating toward something that feels like a real fighting rifle.

If this pattern holds, the final issue gun that lands in infantry units may look a lot closer to this 11-inch, trimmed-down M7A1 than the original heavy Spear.

Major Nidal Hasan is a proper monster. He lacks the vision or ambition of a Stalin or a Hitler. He also doesn’t seem to possess the same sort of dysfunctional source code as did Jeffrey Dahmer—the alpha cannibal. Hasan is a different sort of psychopath. He was cultivated.

To put it in natural terms, Major Hasan was a phasmid. A phasmid is an insect of the order Phasmatodea. Examples include the stick bug or creatures that look like leaves. Their superpower is the capacity to pass themselves off as something they are not. Hasan used his unique capacity for camouflage to murder his own kind.

The Beast

Major Nidal Malik Hasan was born in Arlington County, Virginia, in 1970. His parents were naturalized Palestinians who raised him a devout Muslim.

In 1988, Hasan enlisted in the U.S. Army and eventually earned a spot in USUHS, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences—Uncle Sam’s military medical school.

Hasan was a marginal medical student, spending a fair amount of time on academic probation. He graduated the four-year course in six and completed a residency in psychiatry at Walter Reed.

He then assumed responsibility for helping integrate emotionally-broken combat veterans back into society. Throughout it all, colleagues voiced quiet concerns that Major Hasan just didn’t much care for America or Americans.

The Rampage

On November 5, 2009, Major Hasan showed up at the Fort Hood Soldier Readiness Processing Site with a 5.7x28mm FN Five-seveN pistol.

When he bought the gun three months before, he had asked the guys at the gun shop for, “The most technologically advanced weapon on the market and the one with the highest standard magazine capacity.” Hasan entered the building, bowed his head cryptically, shouted, “Allahu Akbar!” and opened fire.

Hasan shot 32 people. The 14 dead included one unborn baby. Active duty soldiers were all unarmed per standing regulations. A responding civilian police officer shot Hasan five times and finally ended the fight.

Hasan was rendered paraplegic—paralyzed from the waist down and confined to a wheelchair. He was convicted of premeditated murder and sentenced to death.

He made a huge stink about having to shave his beard for his trial, claiming infringement on his religious rights. Hasan currently resides on death row at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. His final appeal was exhausted in March of 2025 when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his case. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth has publicly stated that it is time for Nidal Hasan to die. Convicted murderer Nidal Hasan.

Convicted murderer Nidal Hasan.

The Death House

I once spent three months at Fort Leavenworth. Relax, I was there for an Army school, not a criminal sentence. However, I did get to tour the prison. That included the very place the monster will meet his god should Uncle Sam follow through on his threats. It was a profoundly moving experience.

Everything about the process is codified into a Standard Operating Procedure. Nobody has to think. In my day it was a big three-ring binder. I’m sure it is computerized now. When it is time, the prison staff just opens up the book and does what it says.

Twenty-four hours prior to execution, the prison SWAT team secures the prisoner and moves him to a holding cell.

The convict has no input whatsoever. For a full day, three shifts’ worth of MPs stare at him to make sure he doesn’t kill himself before the government gets its chance. That’s where he takes his last meal. A couple of hours before the big event, the SWAT team shows up again and walks/drags the condemned down a series of stone steps to the place of execution.

Details

The actual room has one-way glass on two sides. One facet is for government witnesses. The other is for victims’ families. The interior walls are covered in soundproofing material. The table has arm supports like a Christian cross with heavy, leather restraints aplenty.

Once the man is strapped down, Army medics start two large-bore IV lines. These lines disappear into holes in the wall. Physicians take no part as that would violate the Hippocratic Oath.

On the other side of the wall, there are two matching closets. The fixtures seemed relatively crude, having been crafted by the prisoners themselves.

In each closet is a holder for an IV bottle. One includes normal saline. The other contains some lethal concoction. They are held in the fixtures upside down. There is a red and a green light in each little room. This is where the two executioners work.

Outside, there are five sequential landline telephones. This is so that, should there be a last-minute stay, word will get through no matter what. The ceiling is made from those ubiquitous acoustic ceiling tiles. This is the last thing the condemned man will ever see.

Hanging from the ceiling is a small microphone. The prison warden reads out the charges and then starts a watch. The convict has three minutes to say anything he wants, then the warden leaves…even if he’s not done talking. The lights change, and the executioners flip the bottles. When the monster dies, he dies alone.

Ruminations

I naturally stretched out on the table and stared at the ceiling, imagining what that might feel like for real. It seemed a bit like being at the dentist. You’d want to be anyplace in the world but there.

It doesn’t matter how bad a man you are or what brought you there. I suspect the utter helplessness of the thing would strip a guy of any bravado or swagger. Major Nidal Malik Hasan will likely soon get to put that hypothesis to the test. May the One True God have mercy on his soul, because the United States of America most certainly will not.

You’ve heard the expression: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Well, the M16A1 wasn’t exactly broke, but after its performance during the Vietnam War the United States Marines Corp requested the M16A1 be “fixed.” Perhaps it would more correct to say modified.

By 1979 when the request was received from the Corp, the modern battlefield was changing. Compared to the M14, the M16A1 was lightweight, had little recoil, and was easy to maneuver, but those who foresee the changing nature of warfare identified a need to change. The range in the anticipated new era of wars would be longer — 300 to 400 meters. In Vietnam, the average engagement distance was a short 25 meters.

A new bullet was being fielded, too. You might have heard of the M855? The bullet’s weight was increased for better long-range accuracy, and a steel tip was incorporated to punch through body armor. Those were two reasons the analysts had to revamp the A1.

The boots on the ground, the Marines in particular, had reasons, too. A lot of reasons. It would seem the M16 needed to be a rifle with downrange performance more like the classic M14.

M16A2 Barrel Improvements

Let’s take barrel first. The A2 barrel is 20” long and has a 1:7-inch twist rate to better stabilize the heavier, longer bullets. The A1 also had a 20” barrel but with a 1:12-inch twist, which was fine for optimizing lighter, 52-gr. bullets like M1193 ball ammo, but has a harder time stabilizing heavier bullets.

The barrel contour of the A2 is also beefed up forward of the handguard. Under the handguard, the barrel diameter is thin and exactly the same as the A1 to allow attaching the M203 grenade launcher.

The three-prong “duck bill” flash hider on the A1 had a habit of getting vegetation stuck in it as well as kicking up dirt or whatever was on the ground when shooting prone. A new A1 “bird cage” flash hider was enclosed so no debris could get caught in it, and slots were cut all around the circumference.

For the A2, the slots on the bottom of the flash hider were omitted so no dust is blasted when shooting prone. In addition, it acted like a muzzle brake to stifle muzzle rise during recoil. One thing that didn’t change was the rifle-length gas system, which makes both the A1 and A2 a soft shooter compared to a carbine- or even a mid-length gas system.

A2 Has Better Sights

Being based upon the M1 Garand, the M14 was always renowned for its excellent iron sights. Conversely, one of the most distinct features of the M16A1 and the A2 is the built-in carry handle on the upper receiver that incorporates the rear sight. The A1 had a flip up aperture sight with two sizes of aperture, flipping the aperture also selected a range. Not the best set up for long range shooting.

The Marine Corp’s adaptation had the A2 incorporate a fully adjustable rear sight with click adjustments for both windage and elevation from 300 to 800 meters. The A2’s aperture also has two settings; the small aperture is for daylight and precision shooting, and the large aperture is meant for low-light scenarios.

The front sight on the A2 also changed to a flat faced post adjustable for elevation with four positions. The A1 had five settings and a round post, which created an aberration in certain light conditions causing groups to be off center.

Additional M16A2 Upgrades

The length of pull on A1 stocks was frankly too short, and also developed a reputation for a lack of durability. The A2 stock was made of stronger Zytel-type material that’s a glass filled thermoset polymer. The LOP was lengthened .62”, and the buttplate uses a toothy texture that didn’t slip out of your shoulder pocket like the A1 was apt to do. The hinged trap door to hold cleaning rods was retained.

A big departure was the handguard, which is round, symmetrical and interchangeable on the A2. It was also made of a stronger polymer. The triangular A1 handguard used a left and right handguard. An interesting note is that soldiers more frequently dropped their A1s on the right side, which meant more right handguards, than left, needed to be in stock. The A2 pistol grip incorporated a finger hook which was designed to keep a user’s hand in place but in reality never really fit anyone’s hand that well.

The A2 changed to a three-round burst in lieu of full auto. The selector switch and the internals went from SAFE-SEMI-AUTO on the A1 to SAFE-SEMI-BURST on the A2. The auto setting on the A1 was found to waste a lot of ammo and was difficult to aim, especially under the stress and excitement of an engagement.

A brass deflector, basically a metal protrusion, was built into the upper receiver specifically for left-handed shooters, which is about 12 percent of the U.S. population. With the A1, hot brass is flung in front of a left-handed shooter’s face. This handy addition ensured the rifle was easy to use for both right- and left-handers.

Legacy of the M16A2

Unquestionably, the A2 variant was a huge step forward in making the M16 rifle more modern and effective. The M16 represented a sea change moment in firearms design, combining modern materials and manufacturing with a new “light and fast” approach to bullet design. In fact, the A2’s adaptations led to the development of the M4 Carbine so common these days.

However, there’s something to be said for the charms of the wood and steel M14. Was its heavier construction, traditional materials and .30-cal. chambering less than ideal for the jungles of Vietnam? Arguably, yes. Was its robust construction, excellent sights and powerful chambering an appealing and capable combination of characteristics in a service rifle? Unquestionably.

There’s an argument to be made that the USMC was trying to turn the M16A1 — through its A2 modifications to the rifles’ construction, operation, long range performance, and durability — into something more like the old M14.

Whatever the motivations, the M16A2 stands as benchmark in modern rifle design and is now as iconic as it is classic.

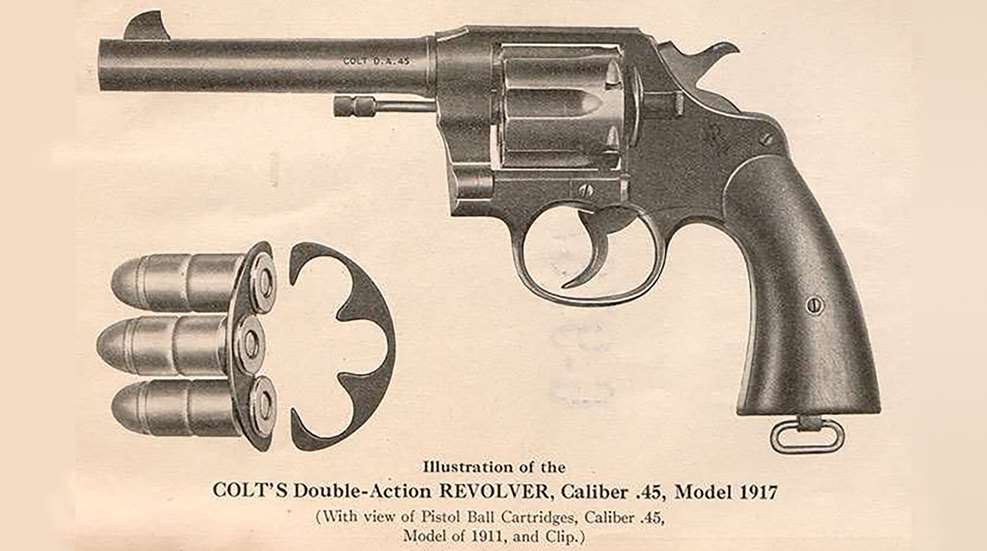

Revolvers have been part of the US military arsenal for a long time. In fact, despite the 1911 semi-automatic having “won two World Wars!,” the revolver continued in US military service longer than that 1911 to 1985 time period. Both the Army and the Air Force kept revolvers in their inventory well past the end of the Vietnam War.

As late as the 1988 edition of Field Manual 23-35, the US Army revolver inventory was listed as “six basic caliber .38 service revolvers in use by the Army.” One 2-inch barreled .38- caliber revolver and five 4-inch barreled .38-caliber revolvers were still in use.

The snub was used by Army CID and counterintelligence personnel, while the 4-inch barreled revolvers were used by aviators and Military Police. The US Air Force didn’t retire the last of its Smith & Wesson Model 15 revolvers until 2018. By that time, the Model 15s were only used with blanks to train working dogs.

One of the earliest 20th century examples of US military revolver training is presented in the US Navy manual “The Landing-force and Small-arm Instructions, United States Navy, 1912.” The techniques shown in the manual, e.g., cocking the pistol, demonstrate how much evolution has taken place in military revolver training. Even then, safety was an issue that had to be emphasized. “In shooting from shipboard, men should be cautioned against standing where poorly aimed or accidental shots may be deflected from boat davits.”

One of the earliest 20th century examples of US military revolver training is presented in the US Navy manual “The Landing-force and Small-arm Instructions, United States Navy, 1912.” The techniques shown in the manual, e.g., cocking the pistol, demonstrate how much evolution has taken place in military revolver training. Even then, safety was an issue that had to be emphasized. “In shooting from shipboard, men should be cautioned against standing where poorly aimed or accidental shots may be deflected from boat davits.”

Just as at the beginning of The Great War, the beginning of World War II saw the military woefully short of 1911 pistols. During the pre-war buildup, the Model 1917 .45 ACP revolver was pressed into service to provide training sidearms for the millions of troops who fought the war.

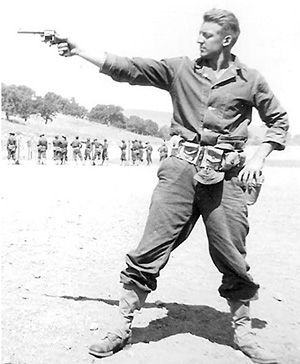

The author’s father was familiarized with a 1917 revolver in basic training shortly before Pearl Harbor was attacked. One handed bullseye target shooting was still the initial form of pistol shooting taught.

Train For Combat, Not The Range

As the War progressed, it became clear that training only for bullseye target shooting was not adequate to train men for combat. Combat firing courses pertinent to both semi-automatics and revolvers were developed. After the war, an interesting development in training that was pertinent to revolvers occurred. The reason for this development is historically unclear.

Change No. 2 to Field Manual 23-35, was issued in 1948. It contained an interesting addition to handgun training that was intended for both semi-autos and revolvers. The addition was the Advanced Firing Course. The course was designed “for use by specially qualified individuals whose military duties demand above average performance with handguns. … Any pistol or revolver may be used, providing it is of sufficient caliber to be effective. Generally speaking, this confines calibers to .38 or larger. Exceptions are the .30 Luger, Mauser, and Russian, and the 32-20 cartridge.”

The course was divided into six tables totaling 50 rounds. The targets ranged from 50 yards to 7 yards. Other than the 50-yard table, it was shot on paper silhouette targets of varying sizes and heights. All the tables under 50 yards require drawing from the holster with some tight time limits. Single-action revolvers were specifically allowed as demonstrated by the reloading requirements in Table XI. Including this category of revolver is curious, although many were furnished to Great Britain during the War.

Recognition of what constituted meaningful handgun practice was included in the course description with a caveat. “Movement not included. The course does not include shooting at ‘running man’ targets, shooting while the firer is running, or a combination of the two. Nor does it include shooting from a moving vehicle, shooting while seated behind a desk, or night shooting.

It is felt that while all these are valuable and should be included in familiarization practice, they involve too many complications to be included in a fixed course of fire.” This emphasis seems to have had its roots as much in clandestine OSS type operations as in the law enforcement role.

Out With The Old, In With The New

The 1960 edition of FM 23-35 was completely restructured, and the Advanced Firing Course was eliminated. The Colt Detective Special was the only revolver mentioned and received a separate section from the 1911 pistol. The Advanced Firing Course for all handguns was replaced for revolvers by the Practical Qualification Course.

The course fundamentals were stated as “Qualification in practical revolver shooting includes firing from several positions at varying ranges; shooting with the right and left hands; point (crouch) firing; double action; and hip shooting.” In this sense, it had become a parallel to the FBI’s PPC, since revolvers were now relegated to the law enforcement function in the Army.

A further evolution of revolver training occurred in the 1988 edition of FM 23-35, which was titled “Combat Training with Pistols And Revolvers.” In place of the Colt Detective Special, the Smith & Wesson Model 10 had become the CID sidearm while aviators were equipped with 4-inch revolvers. Reactive silhouette targets had replaced paper targets of both bullseye and silhouette versions.

The Combat Pistol Qualification Course in the 1988 edition could be used for both pistols and revolvers. Changes to range layout required soldiers to engage single and multiple targets at various distances.

In addition, soldiers were given 40 rounds to fire the 30 targets. This enabled soldiers to fire makeup shots on targets they missed. The manual specifically stated, “A firer who can successfully reengage the target with a second round during the exposure time is just as effective as a firer who hits the target with the first round. The firer is not penalized for using or not using the extra rounds he is allocated.” Making allowance for follow-up shots was a noticeable change in doctrine from years past.

The USAF continued to use revolvers in the law enforcement function for a time but eventually the M9 Beretta replaced it for all but dog training. Finally, even this usage was discarded. Revolvers are no longer part of the US military inventory, but still had a very long period of service that deserves recognition.