Category: The Green Machine

The United States Air Force’s decision to divest the A-10C “Warthog” has larger ramifications for future wars than just an airframe. The service plans to drastically reduce its capability and capacity to provide Close Air Support (CAS) to ground forces, leaving the sons and daughters of America and her allies to fight without a dedicated CAS aircraft for the first time since Vietnam.

History First

The venerable “Warthog” is viewed by some as a Cold War relic that only exists as a jobs program for congressional representatives. This is myopic.

With nearly four decades in service, the A-10C stems from the lessons (re)learned after Vietnam. From inception, the A-10C was a purpose-built CAS platform with demonstrated battlefield survivability. Because of its rugged design paired with heavy and diverse payloads of modern stand-off decoys and weapons, each A-10C delivers more firepower to support ground forces than its fighter counterparts. Further, its AAR-47 missile warning system is especially effective at defeating nearly all Man-Portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADS).

I spent a 24-year career as a Marine Infantry Officer, later transitioning to Marine Special Operations Command (MARSOC), commanding at the Team, Platoon, and Company levels in both Joint and Combined combat environments.

On September 26, 2007, my platoon was on the receiving end of a complex ambush against an entrenched enemy. We fought our way out, often engaging enemy fighters inside of 100 meters and sometimes at hand-grenade range. In a difficult and violent action, we broke the back of the enemy’s assault.

We used two A-10Cs to destroy the enemy element isolated in a trench line. The A-10C’s impressive firepower and danger-close delivery of bombs facilitated the extrication of my 35-member assault force without a single U.S. casualty. This simply would not have been possible without the A-10C working in close consonance with my Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC); a trained air support employment specialist.

I’m a living testament to the A-10C’s utility.

The Issue

In its 2023 budget, the Air Force revealed a 5-year plan to eliminate its A-10C CAS aircraft without an adequate replacement and to cut Terminal Air Control Party Specialist/Joint Terminal Attack Controller (TACP/ JTAC) manning by 50%.

The USAF is a staunchly fighter-oriented culture where platforms like the F-35 and the NGAD fighter are touted as machines that will provide CAS and fight enemy aircraft with equal aplomb, but the Air Force’s plan will divest nearly all close support expertise, crippling America’s ability to employ airpower in close proximity to friendly forces on the ground. Ground troops would be supported by a small, expensive fleet of fragile aircraft that are far less effective at CAS than the A-10C. In low-intensity conflicts, it will cost lives. In Major Combat Operations, it risks losing battles.

Problem Framing

The U.S. is terrible at predicting the next battlespace and future wars. Having a robust quiver of options is better than eliminating a proven platform like the A-10C. Paradoxically, if the USAF follows its own doctrine to justify getting rid of the A-10C this only bolsters the case for keeping it.

No aircraft engages the enemy alone. Much like ground forces use “combined arms” (tanks, artillery, infantry, and aviation) to prevail on land, the Air Force uses “Force Packaging” to win in the air. The four major threats to aircraft over a modern battlefield are:

- Air (enemy fighters);

- Radar-guided Surface-Air Missiles (SAMs)

- Air Defense Artillery (ADA), and;

- Man-portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADS)

The Air Force spends a lot of taxpayer dollars to ensure its fighter team (F-16; F-15EX; F-22; and F-35) can kill or negate enemy aircraft and radar SAMs, but the sensitive skins, engines, and reduced capacity for flares make these aircraft extremely vulnerable to ADA and MANPADS. In contrast, the A-10C is by far the most survivable aircraft against ADA and MANPAD threats found directly above the battlefield and is the only CAS platform specifically designed to protect ground forces in battle.

In a firefight, I sought to dominate high ground, known as “key terrain,” to achieve tactical superiority. The airspace directly overhead the battlefield is the ultimate key terrain. An American ground commander fighting against a capable and determined adversary needs an aircraft with a massive amount of firepower and eyes on both friendly troops and the enemy. Without the A10C’s capability, the USAF cedes the most important position on the battlefield where CAS is a powerful surgical tool. I can’t imagine fighting without A-10Cs which provided me a critical advantage in a dynamic, highly-contested combat environment.

Further, the A-10C was designed to operate from expeditionary airstrips. This works to the A-10C’s advantage in peer conflicts. Advanced fighter aircraft require concrete or asphalt surfaces of at least 8,000 feet in length. Countries like China will use any weapon they can, like ballistic and cruise missiles, to negate aircraft carriers and airfields capable of supporting fighters. Alternatively, the A-10C can island hop around the Pacific with a small support package and operate from 5,000 to 6,000 feet of dirt, grass, or even a short stretch of highway.

The A-10C thrives using a combination of Force Packaging and intelligent tactics, as evidenced in the 2016 deployment of the A-10C to support U.S. forces in Syria. Although Air Force leadership and Beltway pundits would prefer Congress forget about the A-10C operating within multiple surface-to-air missile engagement zones and merging with Russian fighters during Operation Inherent Resolve, the A-10C proved itself on the modern battlefield.

Dollars and Sense

The decision to divest the A-10C is not new; the platform is always considered for retirement when the USAF talks of modernization. The Air Force’s voracious spending habits force an ever-smaller fleet of overpriced aircraft; a single F-35 costs nearly $145 million, which doesn’t account for the billions of dollars spent researching and developing emerging design technologies. Once procured, F-35 operating costs are more than double that of the A-10C, with sustainment costs three times budget expectations.

The A-10C needs a tech refresh, but the aircraft is paid for, and there is little to suggest that the A-10C can’t maintain its relevance with ~$3 million each in modernization and upgrades. That is pennies on the dollar compared to the F-35; the 10-year cost to replace A-10Cs with F-35s is $68 billion. The USAF, just ten years after the initial fielding of the F-35, spent $4 billion dollars on the research and development of an engine it no longer plans to procure. For comparison, it cost less than $1 billion to build and install new wings on the entire A-10C fleet, and another $1 billion could create an all-new, digitally-enhanced A-10EX, capable of employing next-generation weapons, locating threat systems, and acting as an over-the-horizon communications node.

Head-To-Head

Money aside, the Key West Agreement of 1948 charged the USAF to provide Close Air Support to the U.S. Army. The A-10Cs real benefit combines specialists (pilots) with a purpose-built airplane, and the funds used to field the A-10C were pulled from the Army’s own Close Air Support programs. Divesting the only CAS-designed aircraft in the USAF without a replacement is akin to dereliction of duty.

As a mission planner requesting CAS assets for ground operations, I was told to ask for aircraft capabilities to support my mission, rather than specific types of aircraft. Since many aircraft share capabilities (ex. ability to employ GPS-guided munitions) and there are always limited assets to meet multiple demands for CAS, focusing on capabilities creates the flexibility to draw from a variety of platforms to fulfill the requirement.

But this created an argument that U.S. ground forces don’t care what platform delivers ordnance so long as those forces receive it. Advocates of this argument fail to realize that the A-10C is the best CAS platform because of its capabilities. In fact, many JTACs cleverly requested Close Air Support assets capable of “employing forward-firing ordnance, below low weather decks, including 30-millimeter rounds.” This ensured A-10Cs; it provided capabilities no other asset could.

To that point, in June 2018 the A-10C conducted a CAS flyoff against the F-35. The results demonstrated the most effective platform to perform CAS against a peer adversary is the A-10C. The test also highlighted the force multiplication achievable by allowing A-10s to focus on supporting ground forces while fighter assets like the F-35, F-16, and F-18 act in their primary roles to counter air threats and suppress enemy air defenses.

After the fly-off, the A-10C bested the F-35 in CAS, Airborne Forward Air Control, and Combat Search and Rescue mission performance–both in low-threat and high-threat environments. An F-35 pilot was quoted as saying “I need F-35s on the leading edge to detect systems and provide a screen against advanced enemy fighters. I need Warthogs in-depth with the magazine firepower to smite our enemies from the face of the earth.” As a former Ground Force Commander (GFC), I agree. There are two salient reasons for this:

The A-10C has integrated modern technology. First, with four radios and four data-link options that talk to ground troops, its communications package is more compatible with ground maneuver elements than any other fighter. And second, although some A-10Cs are equipped with the newest jam-resistant GPS, its direct-fire weapons and its pilots’ eyes-on tactics negate the effects of GPS jamming. In GPS-denied environments where communications will be severely degraded, other fighters will struggle to accurately deliver GPS-dependent weapons. This is crucial for a GFC in a close fight where seconds feel like hours.

The A-10C also provides an asymmetric advantage by providing CAS from 75 feet above ground level up to 35,000 feet MSL. With moderate speeds and an extremely tight turning radius, which reduces re-attack timelines, the A-10C is responsive, can remain close to friendly forces for long periods of time, and has flexible, forward-firing weapons. These weapons provide more options to quickly engage targets. No other aircraft provides effective CAS in the low-altitude arena, which the war in Ukraine has shown to be one of the few places CAS can be employed in contested airspace.

Unlike the F-35, which requires a prepared airfield to support GFCs from altitudes miles above the battlespace, the A-10C pilot can remain eyes-on friendly forces; enemy forces; utilize targeting pods to generate coordinates for artillery missions; and dominate an adversary in close proximity from tree-top level using 30-mm armor-piercing incendiary rounds, or from 30,000 feet and dozens of miles away using small-diameter bombs.

Humans Before Hardware

The A-10C program is important because it trains pilots to become experts in Joint Fires integration. Their training is directly focused on Close Air Support, Forward Air Control, and Combat Search and Rescue, all of which are complementary missions requiring detailed knowledge of Joint Fires. On June 22, 2016, Joel Bier wrote in The National Interest, “The oncoming challenge is clear: The Air Force must collectively preserve the A-10C pilot manning pool as a force-in-being to save CAS expertise from the dilution of current training and personnel bureaucracy, regardless of its fiscally based hardware decisions.”

Further, Dan Grazier highlighted the inadequacy of CAS training in the F-35 community, showing through official USAF documents that “…no F-35 pilot of any experience level in any component of the Air Force is required to fly a single close air support training mission in 2023 or 2024.” When an aircraft is primarily responsible for destroying enemy aircraft and surface-to-air missile sites, pilots who exclusively train for those missions do not have the time to focus on supporting ground forces. Advocacy for the A-10C is based upon its capability to provide CAS better than any other Mission Design Series. A-10C pilots and the Tactical Air Control Party community maintain that legacy.

There is also a looming 50% reduction of air-ground combat integration specialists. Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) represents the largest proportion of Joint Terminal Attack Control qualified personnel in the USAF. They are experts in Joint Fires integration and the employment of surface and air-based fires essential to successful large-scale combat operations and work directly with GFCs to employ air power. For the U.S. Army, this reduction will eliminate TACP support below the Brigade level in a large conflict. These mission-focused teams of CAS professionals habitually train with A-10C pilots to ensure the safe, proper, and expeditious employment of CAS.

I worked closely with these impressive Airmen during my time in Special Operations where we have a saying that “humans are more important than hardware.” In this case, it proves particularly true, and hobbling the USAF’s TACP manning defies logic since it directly affects the Army’s ability to fight our enemies, particularly peer adversaries.

Ground combat is difficult and at times confusing. As a GFC and qualified JTAC, I could control my own air support in combat. My background and training provided a distinct advantage. I understood ground force fire and maneuver, and I could utilize air support assets to maximize my Marines’ abilities to succeed. However, as a JTAC-qualified GFC, I was the exception; trying to manage CAS while maintaining control of my unit was not optimal.

Having CAS-trained professionals in the air above me and a TACP next to me on the ground is the ideal partnership. A TACP at my side, focused on using air to achieve my intent for CAS, significantly improved my unit’s effectiveness. This is especially important in dynamic, asymmetric environments where high-altitude aircraft dropping bombs on coordinates without eyes on the battlefield will be worthless at best, and cause fratricide or civilian casualties at worst.

Loss of the A-10C and a preponderance of TACPs will create a huge gap wherein a dedicated CAS team doesn’t exist for use in combat like the ongoing war in Ukraine; tailor-made for the A-10C as I wrote about here.

The True Cost

One of the SOF truths is “competent [forces] cannot be created after the emergency occurs.” Getting rid of the A-10C; its qualified CAS-trained pilots; and the air-ground integration expert TACPs is a recipe for disaster.

Vietnam demonstrated that America doesn’t like to wage wars with overwhelming pain to its people. I don’t know what future war holds, but I do know that the largest risk is assumed by ground forces who will go to war without adequate platforms and the flexible engagement options required to fight effectively. That Congress and the DoD are ignoring this is a mistake of epic proportions.

The American public deserves an explanation of why the Air Force is putting American sons and daughters at risk and should have an opportunity to weigh in on this incredibly important and costly decision. For more information and to contact your congressional representatives, please visit https://www.troops-in-contact.org/

Ivan F. Ingraham is a freelance writer and veteran. He served for 24 years in the U.S. Marine Corps as a Special Operations Officer. This is his first submission to The Havok Journal.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

The equipment used during the War of 1812 was relatively similar to equipment used during the Revolutionary War. However, some technological advancements were made, and the War of 1812 was one of the first wars in which almost all items that were issued to soldiers were manufactured and created in the new nation.

Firearms, Weapons, and Related Equipment

Most of the firearms used by soldiers in the War of 1812 were small arms weapons. Flintlock firearms were widespread, and the most common firearms used were the Springfield Model 1795 musket and Harper’s Ferry 1803 rifles. The Springfield Model 1795 musket was produced by inventor Eli Whitney, the creator of the cotton gin, based the design of the firearm heavily from the French Charleville Model 1763 musket that was used during the French and Indian War.

One of the newer technologies to be developed in firearms technology was the use of rifling as seen in the Harper’s Ferry 1803 rifles. Rifling was a feature within the barrel of the firearm that gave the projectile a spin, which led to greater accuracy at longer distances. However, these rifles could not have bayonets attached to them, which caused the 1795 Springfield musket to remain as the most prominent firearm of the War of 1812.

All firearms in the War of 1812 utilized a flint-lock system of firing. Flintlock firing mechanisms were firearms that used a shard of flint (a stone that can easily create fires) to light gunpowder in a pan, which then ignited the gunpowder poured inside of the firearm, which launched the projectile. Flintlock firing systems were first introduced in France in the late 1500s to early 1600s. They were later replaced in the United States by the percussion cap system in the Mexican War and were widespread in the Civil War.

Besides the firearms themselves, soldiers carried items that helped them efficiently reload and maintain their firearms. These items included a leather cartridge box which contained the cartridges that were loaded into the firearm.

These cartridges were wrapped in paper, and had 125 grains of gunpowder, as well as the projectile itself. Extra pieces of flint were also stored in the cartridge box in the case of the flint wearing down too much. A cloth, as well as a musket tool were also included in the cartridge box to clean, maintain, or repair the firearm.

Other weapons that some soldiers carried were bayonets, swords, and pistols. Pistols were used for extremely short ranges of thirty feet or less. They used similar cartridges and utilized flint in their firing mechanisms. Bayonets were most commonly attached to the end of muskets and were used for close quarters engagements. Swords were often utilized by officers and cavalry soldiers.

Clothing and Personal Effects

U.S. soldiers were issued a knapsack that included all their personal effects. For clothing and cloth items, soldiers were issued a blanket, linen shirts, linen trousers, extra socks, fatigue blouse, and fatigue cap. Fatigue blouses and caps were used when not engaged in combat and mostly used for daily drilling and everyday wear.

These cloth items were also used primarily in the summertime. Fatigue blouses were also used for when weather conditions were poor, such as rain. Soldiers would wear the fatigue blouses over their uniforms to prevent rain from getting on their uniforms. Soldiers were also issued their helmets; a tall leather hat called a brain cooker. These hats were uncomfortable, but they made soldiers appear taller when facing the enemy.

U.S. soldiers were also issued wool items. Primarily, their uniforms were made of wool. However, soldiers also received wool trousers and a wool waistcoat. Mostly worn during the winter months, these items would keep soldiers warm while off duty and in the barracks.

The soldiers also received a knapsack of items that were used as a personal locker. These items included items for shaving, such as a razer, shave brush, shave soap, and shaving bowl. There was also a comb, a deck of playing cards (despite gambling being illegal in the barracks), a quill pen, and ink well. These items were crucial in ensuring that the soldiers were well equipped to successfully carry out their duties as a soldier.

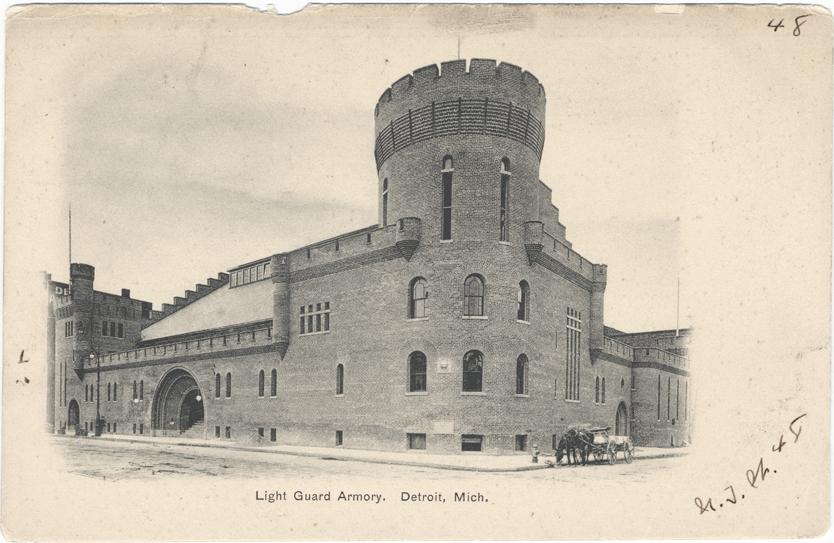

The 1225th Support Battalion has served the city of Detroit since before Michigan was a state. Formed in 1830-1 as the Detroit City Guard, the unit was called into Federal service for the first time in May 1832 for the Blackhawk War under Captain Isaac Rowland. On April 13th, 1836 the unit was reorganized into the Brady Guards in honor of General Hugh Brady. Major General Winfield Scott personally thanked the Guard for mobilizing twice during the Patriot War along the Canadian frontier in 1838-9.

Many members of the company, including future Civil War General Alpheus Williams, served in the 1st Michigan Volunteers during the Mexican War, but the company itself spent the war on patrol along the Canadian frontier. In 1851, the company merged with the Grayson Guards and in 1855 changed their name to the Detroit Light Guard. The Guard was an active organization, working with many elite Northern militia companies, such as Ellsworth’s Zouaves, in the years leading up to the Civil War.

With the coming of the war, the best members of the Guard stepped forward to form Company A of the 1st Michigan Volunteers (Three Months), who arrived in Washington on May 16th. The citizens cheered the men as the first western regiment to arrive in the capital, and drew the comment from President Lincoln, “Thank God for Michigan.”

At Bull Run, the 1st Michigan played a prominent role on the Union right flank on Henry House Hill and advanced farther than any other Federal regiment during the battle. Days later, the regiment returned to Detroit to reorganize into a three-year regiment, and the Detroit Light Guard officially demobilized.

However, Company A remained the active part of the unit, as many members reenlisted with the 1st Michigan. The regiment served in the 1st Division, 5th Corps through the end of the war. They were on the left of the Federal defenses at Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill during the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond.

The 1st Michigan was in the thick of the fighting on August 30th, 1862 at Second Manassas in Porter’s attack on Stonewall Jackson’s position. The fighting in front of the railroad cut was fierce and bloody, particularly due to Longstreet’s artillery that took the attack in the flank.

Half of the regiment fell, and Colonel Roberts, a member of the Detroit Light Guard, was shot through the chest and died shortly after. The unit sat in reserve during the Antietam Campaign but was at the center of the fighting at Fredericksburg in the assault on Marye’s Heights, losing 47 men in the relentless but futile attacks.

At Gettysburg, Lieutenant Colonel William Throop, also of the Guard, took command early in the fighting and led the regiment in their defense of the woods on the west end of the Wheatfield.

The Guard was the first infantry unit to engage Lee’s men at the Wilderness in the Overland Campaign. On May 8th, the regiment left the fighting with only 23 men in the ranks. The 1st played a significant part in the counterattack at Jericho Mill on May 23rd, stemming Wilcox’s breakthrough of the Union lines.

It also fought at Bethesda Church, the opening assaults at Petersburg, and was in reserve at Weldon Railroad in August. In September, at Poplar Grove Church, it stormed two enemy fortifications and part of the lines alone. The 1st fought at Hatcher’s Run, White Oak Road, Five Forks, High Bridge, and Appomattox. They stood in ranks with the rest of their division to receive the surrender of Lee’s infantry on April 12th, 1865.

Following the muster out of the volunteer forces at the end of the war, the Detroit Light Guard reformed from the veterans returned home. This was a low point in the militia of Michigan, and by 1870, it was one of three companies left in the state.

The Guard represented the state at the Centennial celebrations in Philadelphia in 1876 and on May 1st, 1882 adopted the tiger as its mascot, a symbol that Detroit still honors as the mascot of their baseball team. During this period, the company maintained its reputation as both a superbly drilled unit and an elite social club.

With the outbreak of war in 1898, three of the Guard’s four companies became part of the 31st Michigan Infantry and shipped out for training camp at the Chickamauga battlefield on May 16th. The 31st Michigan performed garrison duty in Cuba following the Spanish surrender of the island until mustering out in May 1899. The remaining company served with the 32nd Michigan Infantry, which never deployed out of the United States during the conflict.

In 1916, the Guard was mobilized and with the United States’ entry into the First World War in 1917, it was consolidated with the 3rd Regiment of Michigan Militia to form the 125th United States Infantry in the 32nd Infantry Division.

The division reached France in February 1918 and went into training. Its first combat was in the counterattacks during the Second Battle of the Marne in July and August, earning the division the nickname “Les Terribles.” It fought in the Oise-Aisne and the Meuse-Argonne Campaigns and then served in the occupation force in Germany.

The Guard was called up with the rest of the division in 1941 but was pulled from the division in 1942 when it changed into a “Triangular” division.

The Guard spent the war on garrison duty in the United States and, following the war, was split off the 125th Infantry. It moved around and served as an infantry unit in various brigades. In 1967, the Guard helped put down the rioting in Detroit.

In 1992, it was converted from an infantry unit to a logistics unit. Under its current designation, the 1225th Support Battalion, the Detroit Light Guard served in Iraq from 2004-5. The Guard broke ground on its armory in 1897 and has used the building as their drill location since that time.