Capt. Emanuel Victor Voska, U.S. Army

There seems to be a rule somewhere that any time a nation’s founding fathers are depicted in a group photograph or painting, they’re required to adopt a certain gravitas in their expression to help convey not only the momentousness of their deed, but also their own stature as serious men, such as future generations might look up to.

Such seriousness is very much in evidence in an old photograph of the first Czechoslovak National Council, taken presumably at the time of independence in 1918. Nine men, three in uniform, the rest wearing the formal dress of the day; stiff-necked, high collars, pince-nez spectacles, mustaches, some florid, some pointy, stare in the general direction of the camera, but not into it, and none of them smiling.

Except for one.

Today, almost no one remembers him either here in his adopted country or in the two republics that came from the one he played such a heroic role in helping found.

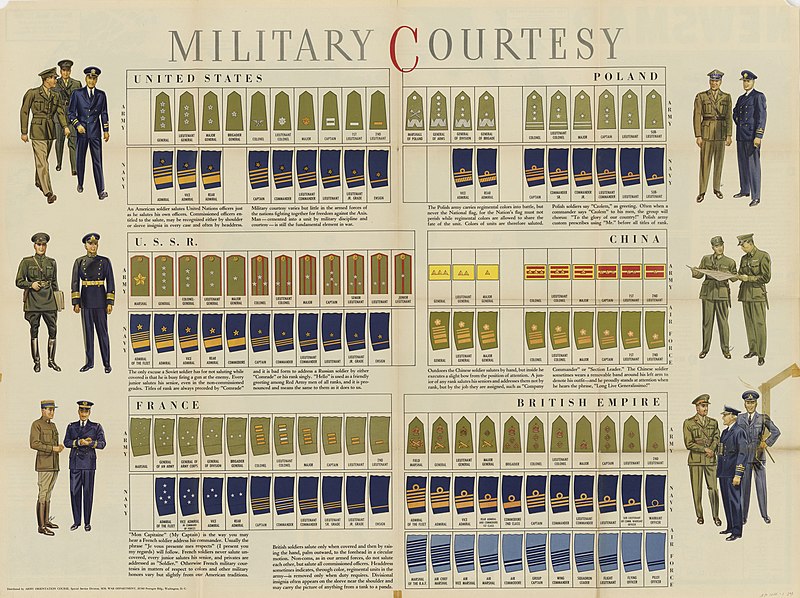

He stands in the very center of the group, behind two seated officers whose uniforms are much fancier than his, which is darker and seemingly without any identifying insignia. He stares directly into the camera, an almost imperceptible smile on his lips, like he knows we’re there, looking at him across a gap of ninety-plus years. He smiles like it’s a secret he’s sharing with us, like he’s someone who knows all about keeping and sharing secrets.

Then you see the narrow, leather strip of a Sam Browne belt coming diagonally down from his right shoulder, and then you notice that on the other there are two gold bars. That’s when you realize that this man is a captain in the U.S. Army.

In this group photo, Voska stands at center, in U.S. Army uniform, just behind the right shoulder of Czechoslovakia’s first defense minister, Vaclav Klofac, with hat off. Wikimedia commons

His name was Emanuel Victor Voska, and besides being a U.S. Army officer and a founding father of Czechoslovakia, he was also one of the greatest spymasters of the 20th century. Today, almost no one remembers him either here in his adopted country or in the two republics that came from the one he played such a heroic role in helping found.

At the time of Voska’s birth in 1875, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was on its last legs. Emperor Franz Josef had already been on the throne twenty-five years and still had another forty left to go. The Czechs, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, Bosnians and other subject nations were growing increasingly restive under his imperial rule and the emperor relied more and more on his vast networks of secret police informers to quash any dissent.

Using his own funds, Voska traveled tirelessly all over the world, connecting himself with thousands of Czechs and Slovaks living overseas, who, though outwardly loyal to the Empire, shared his dream of a Czechoslovak nation.

Trained as a stone sculptor, Voska would have, under normal circumstances, spent his life in his native Bohemia, except that something he said got picked up by an informer and passed on to the police, who paid the young man a visit. Voska decided it was time to leave and seek his fortune in America.

Though he arrived with only a few dollars in his pocket, within a few years he had become a wealthy, powerful businessman. Using his own funds, Voska traveled tirelessly all over the world, connecting himself with thousands of Czechs and Slovaks living overseas, who, though outwardly loyal to the Empire, shared his dream of a Czechoslovak nation. From them he began building vast spy networks that stretched not just all over the globe, but even into Austrian diplomatic service.

Back in the land of his birth, Voska settled down to a quiet life in a farming town. But then fascism started rearing its ugly head in Germany a few miles away, and before long, he was running Czech anti-fascist activities in Spain, working with anyone, including Czech communists, who’d join the cause.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Voska, having already received the blessing of President Woodrow Wilson, put his networks to work for the British, where they scored a number of important coups. With Voska’s help, they smashed German efforts to supply weapons to Irish nationalist groups, both in Ireland and the United States, and a similar operation to start an anti-British revolt in India. Voska also uncovered spy activities by the German Ambassador in Washington and caught an American journalist doubling as a German agent.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, Voska was promptly given a commission as a captain and sent to Russia. His real mission was to make contact with the more than 60,000 Czech and Slovak soldiers who had switched sides after being captured by the Russians. Though some were fighting for the Czar, most were on the sidelines, self-organized into an army whose loyalty was to a nation that didn’t yet exist. Now with Russia teetering toward revolution, Americans needed to know how the Czech Legions might play into the equation. Voska smuggled into Russia Thomas Masaryk, the Czech leader and President Wilson’s personal friend, who urged the legionnaires to stay out of the upcoming turmoil. Nevertheless, events overtook them and the Czechoslovak Legions found themselves embroiled in a war against the Bolsheviks. By the time they’d fought their way home via Siberia and San Francisco, Czechoslovakia had become a nation and Voska was already in Prague helping set up the new government.

Voska spent the next ten years in prison. Some satisfaction did come during show trials, when a number of the same communist leaders who had persecuted Voska were themselves tried and executed for treason.

Back in the land of his birth, Voska settled down to a quiet life in a farming town. But then fascism started rearing its ugly head in Germany a few miles away, and before long, he was running Czech anti-fascist activities in Spain, working with anyone, including Czech communists, who’d join the cause. When the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939, Voska was one of the first Czechs that the Nazis arrested. Somehow he managed to escape to America.

Soon he was back in uniform, this time as a colonel. Voska spent the war in Turkey, overseeing American intelligence operations there and in the Balkans. When the war ended, Voska returned to Czechoslovakia and again tried to live the remainder of his days in peace. Again, it was not to be.

In 1948, the Communists staged a coup and took over Czechoslovakia. For two years, they didn’t bother Voska, because he was someone many of them knew personally and admired. But then Voska was arrested and put on trial for treason. Even though he was now an old man of 75, he fought hard against the charges, arguing that being then an American citizen, nothing he might have done could have been considered treasonous. Voska spent the next ten years in prison. Some satisfaction did come during show trials, when a number of the same communist leaders who had persecuted Voska were themselves tried and executed for treason. What clinched their guilt were old letters found in Voska’s files showing that they had met with him to discuss anti-Franco operations in Spain.

In 1960, the communists finally released the 85-year-old Voska, but he died, a free man, a few days later.