Category: The Green Machine

The Army released its first pictures of the Next Generation Squad Weapon in the hands of soldiers at Fort Campbell, Kentucky on Wednesday.

The XM7 rifle and the XM250 squad automatic weapon were delivered to squads within the 101st Airborne Division in late September as the first operational users of the new weapons.

The two NGSW rifles represent a generational shift for the Army, as the service begins to retire its inventory of personal and squad weapons whose designs date to weapons carried by soldiers in Vietnam. The XM7 will eventually be the new personal weapon for soldiers across the Army, replacing the ubiquitous M4 rifle, whose design dates to the Vietnam-era M16. The XM250 which will replace the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon, a 1980s-era gun.

The new rifles will be used by combat arms specialties like infantry, combat engineers, scouts, and special operations units. The weapon has increased lethality at longer ranges compared to current Army weapons, according to a Fort Campbell’s public affairs office release.

The newly released set of pictures show Fort Campbell Garrison Commander Col. Christopher Midberry and Command Sgt. Maj. Chad Stackpole aiming the two rifles, which appear to be unloaded. The two are shown aiming the two rifles as they might typically be fired in use, with Midberry standing as he aims the XM7 as an infantryman might, while Stackpole is prone as he aims the heavier XM250 on a bipod. The XM250 has no sight attached, but the XM7 appears to be mounted with the XM157 sight, a high tech ranging device that was developed in conjunction with the two weapons.

The XM7 weighs about 8.4 pounds, slightly heavier than the M4, which typically weighs about 7.3 pounds. The XM250 is about 12 pounds, significantly lighter than the SAW, which weighs approximately 18.

The XM7 and XM250 rifles are designed to fire 6.8mm ammunition, a new caliber for the US military and a shift from current issue weapons which use 5.56mm ammunition. The change “was fueled by the need for ammunition with improved armor-penetrating capabilities,” according to Fort Campbell’s public affairs. The new bullet is larger than the 5.56mm used by the M4 and SAW.

The heavier, larger bullet was found to better resist drift and improve range during testing, according to Communications Director Bridgett Siter of the Soldier Lethality Cross-Functional Team at Fort Moore.

The Army’s new 6.8mm bullet can carry as much energy at 250 yards as a 5.56mm round at 100 yards, according to Ammo.com. Both weapons use visual and acoustic suppressors.

The new weapons will be issued with the XM157 optical sight that uses a laser range finder, ballistic calculator, visible and infrared lasers, and a compass.

The Army plans to conduct operational testing to assess the weapons in a wide range of climates and environments, combat conditions, and by paratroopers on parachute jumps.

Army officials have said they expect to buy roughly 107,000 of the rifles and 13,000 of the XM250s to outfit soldiers in nearly every combat arms role in the army. The total contract for the rearming is estimated at $4.7 billion for the weapons and ammunition. Army Times reported the XM157 sights will add another $2.7 billion to the total.

CORRECTION: 10/4/2023. An earlier version of this article identified the firing position of the XM250 in the released photos as being fired from a tripod. The rifle is being fired from a bipod.

An initiative has begun to have 2nd Lt. Ainsworth’s Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which would make her only the second woman to be awarded the medal.

The Sicily–Rome American Cemetery and Memorial is neither in Sicily nor in Rome, but rather it is situated on the northern outskirts of the city of Nettuno on Italy’s west coast. It is so named because it is the final resting place for nearly 8,000 Americans who lost their lives during the liberation of Sicily in 1943, and the campaign to liberate the city of Rome that began soon thereafter with the Allied amphibious landings at Salerno.

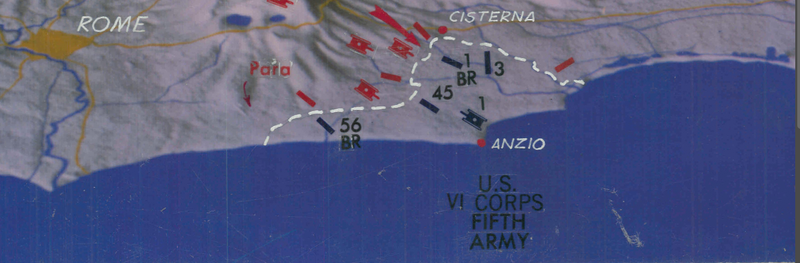

When the battle north of the Volturno River stalled in the Liri Valley shortly before Christmas of that year, an amphibious landing operation called SHINGLE was planned, which ultimately brought an Anglo-American assault force ashore at Anzio on Jan. 22, 1944. The first bodies were buried here two days later.

In 1956, it was officially dedicated as a permanent place of burial, with 7,845 headstones covering a 77-acre site that is just as meticulously maintained today as it was 66 years ago when it was first consecrated. A wide central mall leads visitors from an elliptical reflecting pool past 10 grave plots (lettered A through J) to the memorial itself, which features a statue of a soldier and a sailor on a simple stone plinth in the middle of a columned peristyle. The memorial is flanked by a map room on one side, and a chapel on the other that memorializes the names of 3,095 missing from the two campaigns. A simple “Dedication Tablet” is mounted to the wall at the entrance to the chapel that reads:

1941 1945

IN PROUD REMEMBRANCE OF THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF HER SONS

AND IN HUMBLE TRIBUTE TO THEIR SACRIFICES

THIS MEMORIAL HAS BEEN ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

That tablet should include the word “daughters” as well, because 17 women are buried in the Sicily–Rome American Cemetery. Although their stories are all equally important, one of those women has been receiving some special attention lately, and that is for a very good reason.

Ellen Gertrude Ainsworth was born and raised in Glenwood City, Wisconsin. She graduated from Glenwood City High School in 1936 and, in 1941, the Eitel Hospital School of Nursing in Minneapolis. In March 1942 she enlisted in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps after which she served at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas and then Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Later that year Ainsworth was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and assigned to the 56thEvacuation Hospital before it departed for overseas in April 1943.

After landing at Casablanca, the 56th proceeded onward to the port of Bizerte in French Tunisia in June, and then to the beachhead at Paestum on the Gulf of Salerno, landing there on Sept. 26, 1943. 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth came ashore at Anzio/Nettuno on Jan. 25, 1944 and began treating the wounded just as the U.S. Army VI Corps was consolidating the beachhead there.

Two weeks later, German artillery fire was falling on allied positions daily and the encampment of the 56th Evacuation Hospital was the target of a heavy barrage on Feb. 10 despite the Red Cross markings on the tents.

At the height of the bombardment, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth was directing the removal of 42 surgical patients to an area of greater safety when a shell fragment struck her in the chest. Although she initially survived, Ainsworth succumbed to her wound six days later. She was just 24 years old, and she is the only Wisconsin servicewoman killed by enemy fire in the Second World War.

After her death, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth was automatically awarded the Purple Heart and, ultimately, the Silver Star with a citation reading in part: “By her disregard for her own safety and her calm assurance, she instilled confidence in her assistants and her patients, thereby preventing serious panic and injury.”

In the early-50s, 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth’s mother had the option of having her remains repatriated at government expense, but she chose to let her rest in the Italian soil where her life ended in 1944. She is still there today, less than three miles west of the spot where she suffered the wound that eventually caused her death.

Back home, a building at the Wisconsin Veterans Home is named in her honor as is a conference room in the Pentagon and an Army Health Clinic at Fort Hamilton, New York. In Glenwood City, a bench at the High School athletic complex is dedicated to her and the local post office was named after her in 2016.

While these honors are nothing trivial, there is a distinct possibility that she might eventually be awarded the greatest honor of them all. Recently an initiative to have 2nd Lieutenant Ainsworth’s Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor has begun. If that initiative succeeds, she will be only the second woman to be awarded the medal.

How M18A1 CLAYMORE Works

The U.S. Military Academy no longer will use the motto “Duty, Honor, Country” in its mission statement, according to West Point’s superintendent.

The U.S. Military Academy no longer will use the motto “Duty, Honor, Country” in its mission statement, according to West Point’s superintendent.

The phrase, which was highlighted in a famous speech by Gen. Douglas MacArthur in 1962, will be replaced by a line that includes the words, “Army Values.”

Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth and Army Chief of Staff Randy George both approved the change, which critics may see as West Point going woke.

“Our responsibility to produce leaders to fight and win our nation’s wars requires us to assess ourselves regularly,” Lt. Gen. Steve Gilland wrote in a letter to cadets and supporters on Monday.

“Thus, over the past year and a half, working with leaders from across West Point and external stakeholders, we reviewed our vision, mission, and strategy to serve this purpose.”

Gilland explained that the new mission statement “binds the Academy to the Army.”

“As a result of this assessment, we recommended the following mission statement to our senior Army leadership: To build, educate, train, and inspire the Corps of Cadets to be commissioned leaders of character committed to the Army Values and ready for a lifetime of service to the Army and Nation,“ he wrote.

Gilland made a point to say that West Point’s mission statement has changed nine times and that “Duty, Honor, Country was first added to the mission statement in 1998.”

The general added that “Army Values include Duty and Honor, and Country is reflected in Loyalty, bearing true faith and allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, the Army, your unit, and other Soldiers.”

The academy’s previous mission statement was: “To educate, train and inspire the Corps of Cadets so that each graduate is a commissioned leader of character committed to the values of Duty, Honor, Country and prepared for a career of professional excellence and service to the nation as an officer in the United States Army.”

“The general closed by telling the cadets, ‘In the evening of my memory, always I come back to West Point. Always there echoes and re-echoes: Duty, Honor, Country,'” DeSoto wrote.

“Hopefully, the same will be true for today’s West Point cadets, even with ‘Duty, Honor, Country’ no longer in the mission statement.”