On Friday, September 1, 1939 at 2:50 a.m., President Franklin D. Roosevelt was awakened by a telephone call from the U.S. ambassador to France, William Bullitt, who reported that Nazi Germany had just invaded Poland and was bombing her cities.

“Well, Bill,” the president said. “It has come at last. God help us All.”

Two days later, on September 3, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany and the Second World War was fully underway in Europe. That night, Roosevelt took to the radio waves in one of his customary fireside chats with the American people to lament the situation in Europe. He then added: “I hope the United States will keep out of this war. I believe that it will. And I give you assurance and reassurance that every effort of your Government will be directed toward that end.”

Roosevelt then uttered his oft-quoted thought about war: “I have said not once but many times that I have seen war and that I hate war. I say that again and again.”

What Roosevelt did not say that night was that if and when the nation was drawn into this war, the United States Army was not even prepared to wage a defensive battle to protect North America, let alone stage an offensive campaign on the other side of the Atlantic.

At the time of the invasion of Poland, the German army had 1.7 million men divided into 98 infantry divisions, including nine Panzer divisions, each of which had 328 tanks, eight support battalions, and six artillery batteries.

In stark contrast, the U.S. Army, comprising 189,839 regular troops and officers, was ranked 17th in the world in 1939, behind the army of Portugal. Furthermore, the Regular Army was dispersed to 130 camps, posts, and stations. Some 50,000 of the troops were stationed outside the United States, including the forces that occupied the Philippines and guarded the Panama Canal.

The Army was, as one observer described it, “all bone and no muscle.” The United States Marine Corps stood at a mere 19,432 officers and men, fewer than the number of people employed by the New York City Police Department.

Today, many Americans don’t realize that our nation created a viable citizen army in the 828 days between the beginning of the war in Europe and the “day of infamy,” December 7, 1941. Also largely forgotten was that a fully functioning peacetime military draft system was put in place, and that after a purge of senior officers, a new cohort rose through the ranks that would eventually lead the nation and its allies to victory.

What’s more, the new peacetime army was given a dress rehearsal for the war ahead in the form of three massive military maneuvers in the spring, summer, and fall of 1941, which ended just a few days before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Following Germany’s invasion of Poland and his announcement that morning on Sept 3, FDR formally appointed General George C. Marshall chief of staff of the United States Army, a job that officially made Marshall the president’s top military adviser. A graduate of the Virginia Military Institute, Marshall had been a highly regarded staff officer for General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I. Marshall later became assistant commandant at the Army Infantry School and then deputy chief of staff in Washington since 1938. Some officers in the Army complained that Roosevelt jumped over 20 major generals (two-star generals) and 14 brigadier generals (one-star generals) to get to Brigadier General Marshall.

Marshall came to the job with a mission to prevent the errors of 1917–18, which he had witnessed when planning offensive operations as a member of Pershing’s staff. In September 1918, Marshall helped orchestrate two major U.S. operations in France — the attack on Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensive — both of which, though successful, resulted in the massive loss of American lives. Not only had he witnessed the brutality and waste of war, but he’d seen firsthand the limitations of a poorly prepared force.

At the end of World War I, the Army had contained more than two million men; but since then it had been neglected and allowed to shrink in both size and stature. General Peyton C. March, Army chief of staff at the end of that war, complained that the United States had rendered itself “weaker voluntarily than the Treaty of Versailles had made Germany,” concluding that the country had made itself “militarily impotent.”

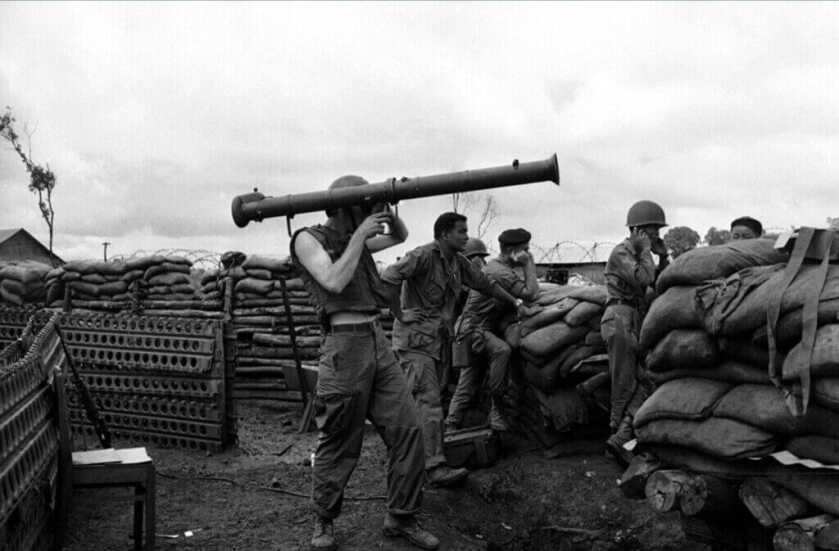

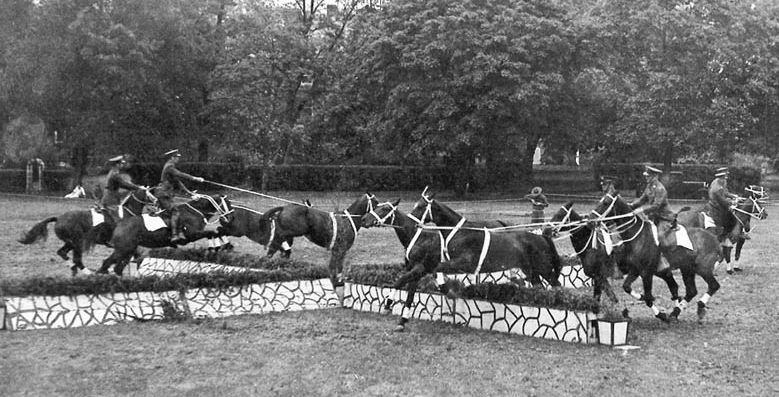

The American Army, with only a few hundred light tanks, was no match for heavily armored German divisions. And it still maintained a horse cavalry as an elite mobile force. Officers who advocated replacing horses with tanks and other armored vehicles between the wars had actually been threatened with punishment. Dwight Eisenhower later recalled that as a young officer, when he began arguing for greater reliance on armored divisions, “I was told … not to publish anything incompatible with solid infantry doctrine. If I did, I would be hauled before a court-martial.”

In the late 1930s, a significant number of cavalry officers became increasingly vocal in their opposition to mechanization and to any attempt to replace the horse with new combat vehicles, especially armored cars. In 1938, Major General John Herr became the chief of cavalry, and his position was that “mechanization should not come at the expense of a single mounted regiment.”

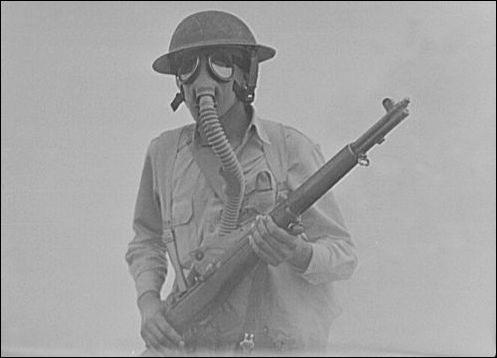

Some soldiers still wore the flat-brimmed steel doughboy helmets from World War I and carried bolt-action rifles from as far back as the Spanish-American War. In 1939, supply wagons were still commonly pulled by teams of mules, and heavy artillery was moved by teams of horses. Soldiers’ pay was abysmal — $21 a month for a private, just as it had been in 1922.

American troops were learning obsolete skills and preparing for defensive warfare on a small scale. “So sorry was the state of the U.S. Army in 1939 that had Pancho Villa been alive to raid the southwestern United States it would have been as ill prepared to repulse or punish him as it had been in 1916,” observed military historian Carlo D’Este.

The United States did have Reserve officers and the National Guard, which required its members to attend 48 training nights and two weeks of field duty per year to fulfill their obligation, but this was hardly enough to prepare them for combat without sustained additional training. Making matters worse, an attempt to get former soldiers to sign up for the Army Reserve, begun in 1938, was failing. Fewer than 5,000 men signed up within the first year, despite the fact they did not have to go to camps or drill but only to agree to be ready in an emergency.

Organizationally, the Army was divided into small sections that hardly ever trained together as larger coherent units because of a lack of funds. The meager budget needed to run the Army had dwindled as the Great Depression deepened. In 1935, the Army’s annual budget bottomed out at $250 million, and the force had declined to 118,750, at which point Douglas MacArthur, then Army Chief of Staff, observed that the entire Regular Army could be placed inside Yankee Stadium.

Upon taking office in 1939, with Franklin Roosevelt’s support and authority, Marshall began creating a new army, purging from it more than a thousand officers he deemed unfit and reshaping the standard Army division by transforming its four large but undermanned regiments into three smaller and more effective regiments with full manpower and greater mobility. Men whose names would become famous in the war in Europe would emerge as stars during the training of the draftees in the 1941 maneuvers. Atop the list was the brilliant but arrogant George S. Patton, a veteran of the First World War.

That same year, Marshall began training three streamlined infantry divisions and one cavalry division for a series of war games that would be staged in an area somewhere in the arc extending from Georgia to Texas. Marshall let it be known that these would be the largest peacetime maneuvers in the history of the United States. He was keenly aware of the need to prepare American infantrymen for a new kind of brutal, fast, and merciless warfare — blitzkrieg, German for “lightning war.”

The invasion of Poland had triggered hopes of Marshall and other Army leaders for substantial increases in U.S. Army manpower. But even then, those who understood that an army had to be raised realized the initiative had to come from outside the White House and Congress. It wasn’t until 1940, after the Nazi invasion of Norway in April, that proponents of an increase in manpower, led by well-connected New York attorney Greenville Clark, proposed that the United States establish its first-ever peacetime military draft. After a long battle for approval, a bill was passed and made into law on September 16, 1940, calling for the registration of all American men between the ages of 21 and 34.

But key members of Congress vowed not to extend the original draft legislation, which called for only one year of active duty. A political battle erupted between those supporting the extension and the continued training of the new army of draftees and those who wanted to bring them home and effectively isolate the United States from global conflict.

The battle reached its zenith only weeks before Pearl Harbor, when the House of Representatives came within a single vote of dismantling the draft and sending hundreds of thousands of men home, which would have all but destroyed the United States Army.

While Clark and his band of civilians had taken charge of the draft movement, Marshall feared that the Regular Army lacked the manpower to train conscripted men while keeping intact for emergency duty on this side of the Atlantic — such as putting down a Nazi-backed revolution in Brazil. He concluded that the solution to this problem would be to activate the whole National Guard, which could absorb thousands of draftees and give them basic training. On August 31, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8530, calling up 60,000 men in units of the National Guard in 27 states.

In all, close to 65,000 officers and men in the National Guard were initially inducted into service and sent off to become part of the Regular Army, which gave the numbers for a standing army an immediate spike. These were the first peacetime tours of service since 1916, when National Guard units had been positioned along the Mexican border while General John Pershing mounted a punitive raid across the Rio Grande in search of Pancho Villa.

As the Army struggled to house, clothe, and equip this first group of men, a second increment of National Guardsmen was federalized on October 15, adding another 38,588 men to a system already bursting at the seams. The third and fourth increments in November brought in yet another 33,000 Guardsmen. By the end of November 1940, 135,500 Guardsmen were in the Regular Army.

As camp conditions stood at their worst, the first group of 13,806 draftees entered the Army in November, adding new stress to the system.

Marshall’s challenges in building these armies were many. A lot of the draftees were malnourished and otherwise suffering under the difficult circumstances common in the Great Depression. Many were not happy about their new status, especially when posted to remote bases, where they were bored and homesick. Some threatened to desert if the original one-year period of service was extended.

In the East, the particularly wet winter of 1940-41 yielded mud of such quantity and depth that roads leading to newly constructed barracks became impassable. The incidence of influenza in the Army rose to approximately four times the level of the previous winter, along with a rise in other respiratory diseases.

The National Guardsmen also faced endless problems. From Camp Murray in Washington State came a report in December that half of the 12,000 men encamped there had influenza.

Compounding this infirmity, the Guardsmen were housed in tents pitched on platforms over wet grounds, while the draftees coming in were ushered into new, dry barracks since the draft legislation specifically stated that they be adequately housed. The commanding officer of the National Guard was asked by a reporter from the Seattle Times how this situation affected his men. “They’re patriotic,” he replied, “but they have wet feet.”

For many of the early draftees and Guardsmen, the situation was exacerbated by local custom and regulation — especially in locales in the portion of the country H. L. Mencken had dubbed “the Bible Belt.” State law in places such as Hattiesburg, Mississippi, banned Sunday movies and forbade dancing within the city limits. The only amusement open on the Sabbath inside the city limits was an arcade with pinball machines — colloquially known as “nickel-grabbers.”

Marshall realized that he had, in the words of his main biographer, Forrest Pogue, “an alarming situation” on his hands. The problems of drinking, prostitution, boredom, and disorder were getting worse.

The houses of prostitution that opened near bases caused the spread of venereal diseases, which had sidelined tens of thousands of troops in World War I and remained a huge concern in an era before antibiotics.

The challenge for Marshall was solving immense structural problems with one hand while building a citizen army full of esprit de corps with the other. Marshall never lost sight of the necessity for good morale if this unprecedented expansion was going to succeed. He also knew that this new army could not be disciplined by fear and intimidation but only through respect—a lesson he had learned from both the Army and his work with men of the Civilian Conservation Corps, who had needed to be convinced rather than coerced.

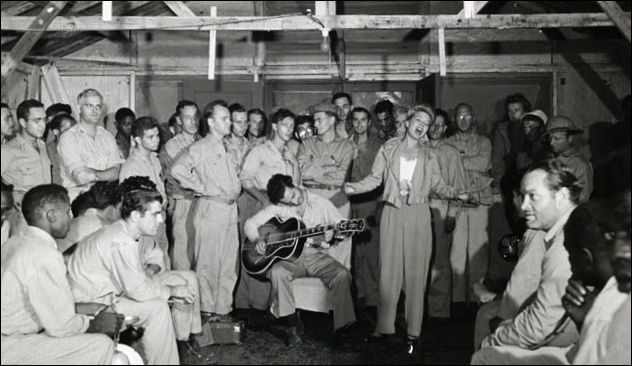

Marshall began to work with the Morale Division on a broad program to create recreational halls on every major base in which men could buy light refreshments, listen to music, and meet and dance with female hostesses. To sustain this massive initiative, the United Service Organizations (USO) was legally established in New York City on February 4, 1941, when several national charities banded together to raise the morale of members of the armed forces providing them recreation, education, and entertainment.

Another key element of the morale boosting was the three realistic war games staged in 1941, in which more than 820,000 new soldiers participated. Conducted in Tennessee, Louisiana, and the Carolinas, the exercises transformed the way Americans would wage war and paved the way for the highly disciplined, fast-moving units, including armored cavalry units led by bold and resourceful officers that led to victory in North Africa and Europe.

Not only did the maneuvers train the men in crucial new weapons and methods of warfare, but they also helped create a new and unique “G.I.” culture that was invaluable in boosting morale and bonding men from all backgrounds into a cohesive group before they set off to fight around the world.

The Louisiana Maneuvers were the largest of the 1941 mock battles and the centerpiece of Chief of Staff Marshall’s plan to give the Army fresh vigor, a higher level of morale, and a new cohort of leaders. Marshall also saw Louisiana as a place to show the nation what it was like to go to war and what it would take to win that war.

Even during the planning stages, the Louisiana Maneuvers were labeled the largest-ever military exercises in size and scope. More than 19 full divisions and some 400,000 men were to be made ready to engage in a mock war, which was approximately the same number of troops on active duty in the United States Army in 2019.

Like the Tennessee Maneuvers, these in Louisiana were unscripted; nothing was prearranged about how they would be conducted or how they would end. The goal was to approximate real combat in a way never achieved before – and the staging would borrow a page from Hollywood. No fewer than 500 of them would drop from the skies over Louisiana and float to the ground ready and armed for mock battle. Actual tanks, including those under Patton’s command, as well as mounted cavalry divisions would participate. Smoke canisters would be released to shroud battlefields, large bags of white flour would be fired from artillery or dropped from aircraft to simulate attacks and mark direct hits while loudspeakers would blast the recorded sounds of battle.

While Congress wrestled with whether or not to extend the service of the draftees and Reservists, troops from all over the country began their trek to Louisiana and staging areas in neighboring states. Many units would remain in the field for five months. Enlisted men could possess only what they could carry, which would mimic the conditions of a real war.

On the eve of the first phase of the exercises, the combat zone came within an eyelash of a direct hit by a hurricane, which changed course and made landfall in the area near Galveston, Texas. The heavy rain and wind only added to the power of the enemy both armies faced: “General Mud.”

The maneuvers were testing whether a superior force without tanks (Blue) could defeat a smaller force with two mature armored divisions (Red). Not stated as such by the men in charge, but understood by a few of the reporters, this setup was akin to the situation the allied nations faced in Europe. As Leon Kay of the United Press noted, when Lieutenant General Walter Krueger gave the order to “advance and engage the enemy,” it was essentially the same order given to the vastly smaller armies in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Yugoslavia when Germany’s columns of tanks and armored vehicles thundered over their borders.

Kay, who had witnessed firsthand the war in Europe and had watched the German invasion of the Balkans, would view the maneuvers through a prism that saw Lieutenant General Ben Lear, as the Nazi, sending his two Red Army Panzer divisions into a nation holding on for its life.

The maneuvers officially began at 12:01 a.m. on September 15, 1941, as rain fell over most of the area. Close to a half million men were now at war. The day got off to an inauspicious beginning, as the 400 aircraft of the Blue Third Army were grounded before dawn after two planes collided and one pilot was killed. Three other soldiers were killed in predawn traffic accidents—fatalities that immediately underscored the exercises were more akin to real war than simple war games.

During that first exercise—officially referred to as Phase I but quickly dubbed the “Battle of the Red River” by the press—the Second Army quickly found that getting across the river was tougher than expected. A lack of bridges strong enough to carry tanks forced Lear to deploy three temporary pontoon bridges. These, along with three strong highway bridges, allowed him to send his First and Second Armored Divisions on a wide pivot northwest, to cross the river at Shreveport and Coushatta, with Patton’s tanks in the lead.

As they began, it was clear that the maneuvers were well staged and above all augmented by top-notch sound effects. “This added realism was so loud that we had to shout to be heard,” commented Captain Norris H. Perkins. Added to this were the other sensory cues suggesting real warfare including the smell of burned powder and diesel exhaust and the distinct odor of cavalry horses as well as the presence of billowing clouds of smoke and dust.

By nightfall, the greater part of Lear’s Red Army had met little opposition as it occupied several hundred square miles of Blue territory. If there was a great success on opening day, it was the placement of those massive pontoon bridges across the Red River. As September 15 came to a close, the expectation was that there would be conflict the next morning.

Inside the maneuvers, a contest within a contest was going on. Before the opening, Brig. Gen. John N. Greely, commanding the Second Infantry Division of the Blue Army, had offered his men a $50 reward for the capture of “Georgie” Patton, “dead or alive.”

Upon hearing this, Patton offered $100 for the capture of Greely. After crossing the river, a group of Patton’s men went looking for Greely and found him in his command post near Lake Charles. The bounty was collected.

On September 18, after three days of preparation, the Red Army thrust more than half of its 130,000 men at the Blue Army along a 75-mile front in central Louisiana, while sending its armored divisions, based on airborne reconnaissance, east rather than west, where the Blue Army had positioned its anti-tank units.

The armored divisions had virtually disappeared for two days, setting up the surprise attack. However, Krueger’s forces discovered Lear’s armored divisions, and the Third Army’s B-26 aircraft attacked them before dawn, dropping flares on the columns.

By nightfall, observers felt that each side still had a chance at defeating the other, but the tide turned quickly the following morning, September 19, when the Blue Army captured most of two regiments of the New York 27th Infantry, which led Hanson W. Baldwin to declare, “Had today’s finale been real war, General Lear’s Second Army would probably have been annihilated.”

A few lessons appeared to have been learned—or at least underscored during this exercise. Major General Charles L. Scott, commander of the First Armored Division, concluded that air superiority and a motorized infantry were needed for the success of tank attacks. “The day of trying to operate without aircraft is past,” he asserted. “And putting foot troops with tanks is like sending a race horse and a plow mule out together and expect them to go at the same speed.”

George Patton’s Second Armored Division had met with overpowering infantry and anti-tank opposition and was essentially destroyed. There was general agreement that the combination of inhospitable terrain, weather, unfavorable umpire rulings, and the anti-tank battalions had combined to defeat Patton’s men. Patton was not only frustrated to be on the losing team but also unhappy that he was unable to pay the $50 reward he had promised to his officers and men for the capture of “a certain s.o.b. named Eisenhower.”

Patton and Eisenhower were old friends, united in part because they both saw a future in tanks. Despite their vast differences in temperament and personal wealth, they enjoyed the highest personal respect for one another. Having been placed on the opposite side in a mock war, Patton thought the best way to humiliate Eisenhower would be to capture him, but his attempt did not avail.

On the other hand, reporters in Louisiana had no trouble finding Eisenhower, who became the face and voice not only of Krueger’s Blue Army but also of the leaders of Marshall’s emerging new U.S. Army. As Ike’s son John Eisenhower explained, Krueger was a reticent man who still retained a trace of a German accent, and he was glad to hand over the role of keeping the press happy and well informed. Because of his good nature, genuine humility, and love of telling stories, the 49-year-old Eisenhower became the counter-stereotype to the no-nonsense, tight-lipped Army field officer.

The Louisiana games were among the most watched and carefully reported events of 1941 — but they were largely forgotten when real war ensued with Japan’s invasion of Pearl Harbor on December 7 and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States on December 11. The maneuvers themselves tell a dramatic story filled with colorful characters and monumental (sometimes comic) missteps, taken as the Army learned by its mistakes. But they are also essential to understanding the United States’ involvement in World War II, and the ultimate outcome of the war.