Category: The Green Machine

The First World War introduced a wide range of military technologies that we take for granted today. Probably the most important of these deadly innovations was the marriage of the aircraft and the machine gun. Beginning with particularly crude modifications and lash-ups, combat aviators on both sides rapidly advanced the effectiveness of the firearms of the first air war. In April 1917, the month that the United States entered World War I, the air war had progressed to such a level that the Royal Flying Corps labeled it “Bloody April,” losing 245 aircraft and more than 400 airmen. The aerial killing machines had become so efficient that the life expectancy of new pilots was measured in just a few days.

Aerial gunnery training begins: Cadets skeet shooting with Winchester Model 1897 shotguns at the University of Illinois during the spring of 1918. National Archives And Records Administration (N.A.R.A.) photograph.

Aerial gunnery training begins: Cadets skeet shooting with Winchester Model 1897 shotguns at the University of Illinois during the spring of 1918. National Archives And Records Administration (N.A.R.A.) photograph.

From First To Worst

In 1917, America was almost completely unprepared for a modern war. Upon joining forces with the Allied nations, the U.S. military found itself without many of the firearms that European combatants already took for granted: heavy artillery, tanks, machine guns and, quite notably, combat aircraft.

Just a decade before World War I, America had pioneered the motor-powered aircraft (December 1903) and, within a few years of the war, became the first nation to fire a machine gun from the air (August 1912). But America’s world-leading military aviation potential was undone with the pen rather than the sword, as the general staff decided that the airplane was only fit for scouting—aerial combat or even bombing wasn’t considered important. Military aviation in the U.S. quickly stagnated, and even though the scouting planes attached to Gen. Pershing’s Mexican Expedition received high praise for their work, when America entered World War I, the U.S. military was without combat aircraft. Even worse, there were no combat-ready airmen or the schools to train them.

Skeet shooting continues: Shotgun shooting with the Winchester Model 11SL at the U.S. Army Air Service training center at Issodoun, France, during April 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Skeet shooting continues: Shotgun shooting with the Winchester Model 11SL at the U.S. Army Air Service training center at Issodoun, France, during April 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The transcripts for the Army budget hearings in early 1917 show that America’s political and military leaders had little understanding of the airplane and the gun. Chief Signal Officer Gen. Scriven responded to the Chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs in the House of Representatives:

The Chairman: How are the aeroplanes armed?

Gen. Scriven: That is another question that is very difficult of solution. They are carrying now merely the service rifle and pistol. Some men think that a short riot gun, a shot gun, should be used; others think that a gun of the Lewis type or some other such type may be well used.

The Chairman: You have not equipped them with the machine gun at all?

Gen. Scriven: Oh, yes; experimentally, we have tried some. We have used the Lewis gun, but they are not mounted. The Lewis gun weighs only 27 pounds and can be used from the shoulder. It is a very good gun.

Mr. Kahn: Are they all armed with Lewis guns?

Gen. Scriven: There are some down there; 14, I think.

Mr. Kahn: Have you ever used any other machine gun, except the Lewis gun?

Gen. Scriven: The Benet Mercie gun was used. We tried it out. I think there are some down there now. We have tried them all out thoroughly.

A trainee in a special turret stand equipped with a Scarff mount—featuring a special adapter to attach a Winchester Model 1897 shotgun. Selfridge Field, Mich., 1918. Author supplied photograph.

A trainee in a special turret stand equipped with a Scarff mount—featuring a special adapter to attach a Winchester Model 1897 shotgun. Selfridge Field, Mich., 1918. Author supplied photograph.

Most members of the committee were completely unfamiliar with the entire concept of air combat or the use of automatic firearms aboard airplanes. Lieutenant Colonel George Squier was recently back from London, where he had been America’s military attaché. Using his first-hand knowledge of the air war in Europe, Colonel Squier explained:

Mr. Kahn: These aerial battles are all fought with machine guns?

Col. Squier: Absolutely. On that point one might add the angle of view of the machine gun as it appears to our Aviation Section. If you will eliminate the demolitions, for instance, where you drop bombs, or the incendiary bomb, and take the pure case of a fight between aeroplane and aeroplane, it would appear that what we want is not a large gun with a few number of rounds, but a small-caliber gun with a large number of rounds, for the following reason: You get the upper berth and come at the opponent by gravity, shooting through the propeller, and you only have a very short time in which to shoot. You then go by him at the rate of a hundred miles an hour, and you come back again, if you are faster than he is. So that if you had a large gun with only one shot and did not hit him at all, your shot would do no good; but if you had the same weight of lead in a hundred shot you would be more apt to hit him; and the aeroplane is so vulnerable at present, that he would be disabled as much by that small shot as by the large one.

Mr. Greene: Col. Squier, I understand that the theory of this combat in the air is to gain control of that territory, for the other purposes for which the aeroplanes are subsequently to be used in it?

Col. Squier: Yes, sir.

Mr. Greene: The fighting itself has no particular military object?

Col Squier: Well, it is to kill the other man.

Mr. Greene: Well, to kill him, but is it in order to get control of the air zone?

Col. Squier: Yes, sir.

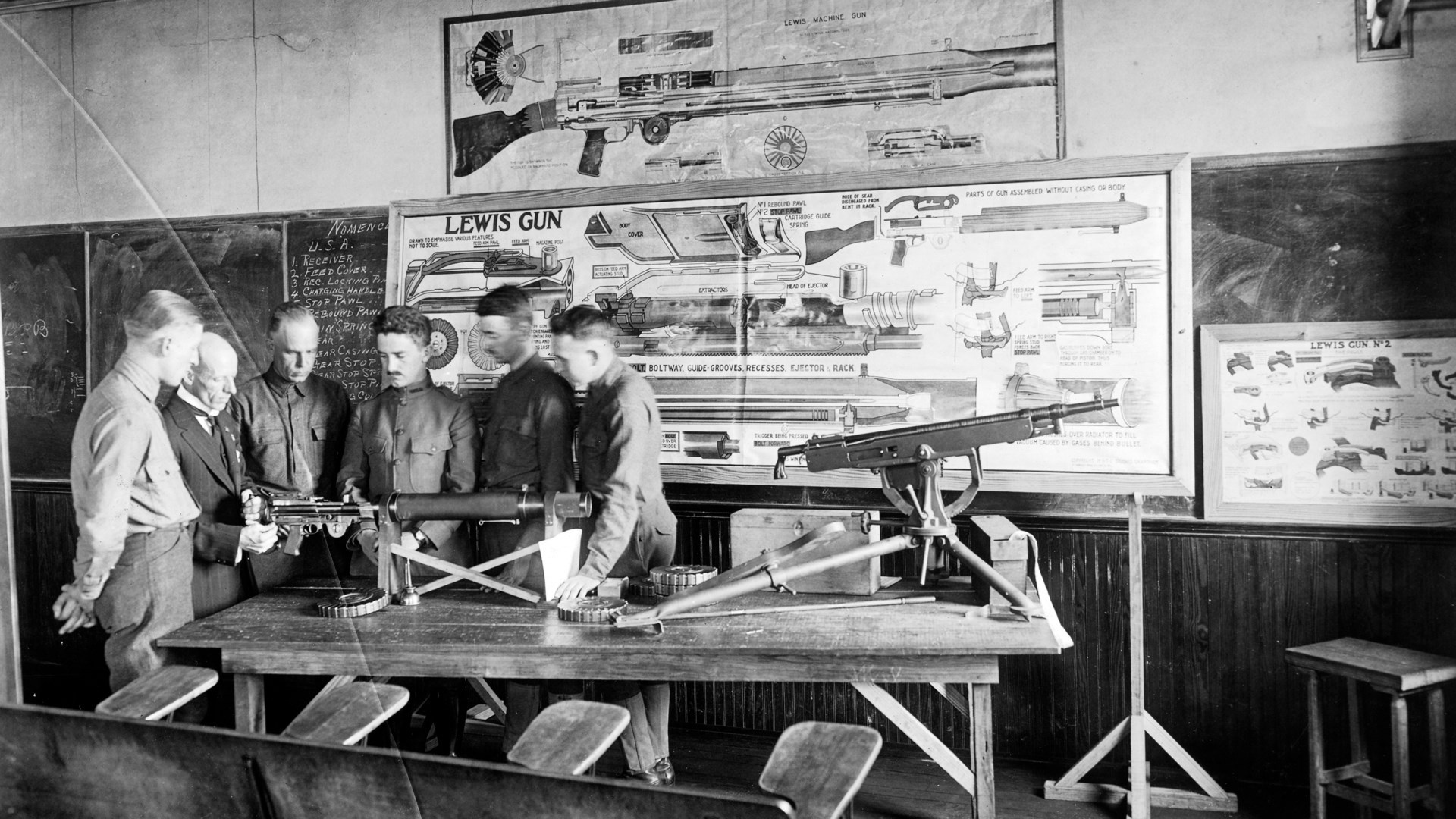

In the classroom: U.S. aviation cadets learn the Lewis gun inside and out while blindfolded. N.A.R.A. photograph.

In the classroom: U.S. aviation cadets learn the Lewis gun inside and out while blindfolded. N.A.R.A. photograph.

America’s fledgling aviators may have been woefully behind in combat aviation technology, but they did have the advantage of being able to learn from several highly experienced allies—the British, French and Italian air services all contributed modern aircraft and veteran pilots to serve as instructors. As American industry began to produce aircraft and aerial firearms at a greater pace, airfields and flight schools sprang up around the nation. The U.S. Army Air Service was quickly taking shape.

Machine Guns Of The Aerial Gunners

The combat aircraft of World War I were not particularly sophisticated—at least in the early stages of the war. Consequently, the relationship between the airman and the machine gun he carried aloft was as tight knit and vital as any machine gunner and his firearm on the ground. America was late in developing machine guns, but trainees in the U.S. Army Air Service were still able to handle two of the prime firearms of the Allied air forces along with a new machine gun that would only see combat aboard American planes.

In the School of Military Aeronautics at Georgia Tech: Aero cadets learn the basics of machine guns. A U.S. .30 -cal. (Savage Arms made) Lewis Gun is seen at the left, and a Colt-Browning Model 1895 is at the right. N.A.R.A. photograph.

In the School of Military Aeronautics at Georgia Tech: Aero cadets learn the basics of machine guns. A U.S. .30 -cal. (Savage Arms made) Lewis Gun is seen at the left, and a Colt-Browning Model 1895 is at the right. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The Lewis Gun

The Lewis was an American design, but Col. Lewis couldn’t convince the U.S. Army to adopt his light machine gun. By early 1914, the Lewis was working with the Birmingham Small Arms Company, and the gun was made in England (in .303 British). Ultimately, the Lewis would become the preeminent defensive firearm for Allied aircraft in World War I—used as a “flexible” or “free” gun for the observer. In some aircraft, the Lewis gun was mounted on the top wing to fire above the propeller arc. There were never enough Lewis guns to truly meet Allied demands for the firearm on the ground or in the air, and some Lewis gun production came back to America. Savage Arms Company produced Lewis Mark I guns (chambered in .303 British and called the Model 1915) for Canadian forces. As America entered the war, Savage produced the .30-cal. M1917 ground gun—some of which were modified for use as aircraft guns. Finally, Savage created the .30-cal. M1918 Lewis, a purpose-built aircraft MG, stripped to save weight and equipped with a bulb-like muzzle brake. By the middle of 1918, the M1918 was mounted on most U.S. and French bombing/observation aircraft.

The Vickers Machine Gun was the predominant forward-firing firearm on most Allied combat aircraft. The Colt-made U.S. M1915 Vickers .30-cal. was used for training in the U.S., and many of the aircraft guns were used by both French and American squadrons. This is a standard infantry gun, seen at Ellington Field near Houston, Texas, during the summer of 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The Vickers Machine Gun was the predominant forward-firing firearm on most Allied combat aircraft. The Colt-made U.S. M1915 Vickers .30-cal. was used for training in the U.S., and many of the aircraft guns were used by both French and American squadrons. This is a standard infantry gun, seen at Ellington Field near Houston, Texas, during the summer of 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The M1915 Colt-Vickers

The Vickers machine gun was the dominant Allied forward-firing aircraft gun of World War I, and this, too, was made in the U.S. in some numbers. The Colt-Vickers U.S. Model 1915 (chambered in .30-‘06 Sprg.) was destined to serve in small numbers with U.S. troops in Europe, and some of the M1915 guns were modified for use as synchronized aircraft MGs. To meet the great demand for Vickers guns, Colt then created the “U.S. Vickers Aircraft Machine Gun, Caliber .30, Model 1918,” which equipped many aircraft in the U.S. and French air services in 1918. Colt also rechambered about 1,000 of the Model 1918 guns to 11 mm French for use against observation balloons. The 11 mm round provided a useful incendiary cartridge (at least the French thought so), and these MGs were called the “Gras Vickers” or the “Balloon Gun.” American aviation cadets often became acquainted with the Vickers gun by using tripod mounted M1915 Colt guns on the target range.

Training equipment was created alongside new firearms. Here, a crude gunnery trainer (equipped with a Marlin aircraft machine gun) is set up at a stateside flight school during 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Training equipment was created alongside new firearms. Here, a crude gunnery trainer (equipped with a Marlin aircraft machine gun) is set up at a stateside flight school during 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The M1918 Marlin Aircraft MG

The Marlin-Rockwell Corporation acquired the rights to produce the old Colt-Browning M1895 MG, and designer Carl Swebilius redesigned the gun, replacing the “potato-digger’s” swinging arm lever system with a straight-line, gas-actuated piston. The result was the Marlin M1917 and M1918 aircraft gun, which were faster firing (at 650 rounds-per-minute) and about eight lbs. lighter than the Vickers aircraft guns. Unfortunately, synchronizing gear and ammunition-feed systems were not ready for the new guns, and this delayed the Marlin’s combat debut until the late summer of 1918. Even so, many trainees had the opportunity to work with the Marlin gun in the U.S., and there was some familiarity with the firearm when it began to reach France in quantity. Although its service life was short, the Marlin made a very favorable impression on U.S. pilots and air crews, and it would have replaced the Vickers if the war had continued.

A Curtiss Jenny mounting an M1918 Lewis aircraft MG equipped with a vane sight. Texas, summer 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

A Curtiss Jenny mounting an M1918 Lewis aircraft MG equipped with a vane sight. Texas, summer 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Aerial Marksmanship

America was born as a nation of riflemen, and that foundation of marksmanship carried over to the fledgling pilots and aerial gunners training in America. One of the biggest problems that the Air Service faced, particularly in 1917, was an embarrassing lack of machine guns. Most of the Lewis guns made in America (by Savage Arms in Utica, N.Y.), were being sent to Canada and France for use with their squadrons. As more U.S.-made Lewis guns became available, many of these were used to train American infantry units.

Photos from the era show that some U.S. airmen began their gunnery training with wooden mock-ups of Lewis guns. Aviation cadets often used the elderly Colt-Browning Model 1895 MGs to get their first live-fire experiences with an automatic firearm. Colt stepped up its production of .30-cal. U.S. M1915 Vickers machine gun, and the tripod-mounted Vickers also helped air cadets get some experience with contemporary machine guns. Knowledge of the Vickers and Lewis guns was particularly important, as once in combat, these were the primary aircraft firearms on U.S. Army Air Service aircraft—the Vickers as the synchronized, fixed, forward-firing armament and the Lewis as the flexible defensive guns for the observers.

In response to shortages of aircraft machine guns and ammunition, the Hythe Mark III gun camera was introduced in 1918 to simulate the size and weight of the Lewis Gun while providing a series of images that showed the trainee’s aiming points. N.A.R.A. photograph.

In response to shortages of aircraft machine guns and ammunition, the Hythe Mark III gun camera was introduced in 1918 to simulate the size and weight of the Lewis Gun while providing a series of images that showed the trainee’s aiming points. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Shotguns played an important role in training America’s first air gunners, and skeet-shooting was thought to be a good way to help cadets become adept at hitting fast-moving targets at a variety of angles. Pump-action shotguns, particularly the Winchester Model 1897, were favored for this training, although some early semi-automatic scatterguns, like the Winchester Model 11 SL, were also used.

Photos and films from the era show various “simulators” built to provide fledgling pilots with the rocking, buffeting and bouncing sensations that would affect their aim. In addition, various targets were constructed—ranging from simple silhouettes of German aircraft on paper targets to scale models made of wood, some used in a hand-cranked pulley system. Some pilots did a little training with their M1911 pistols or M1917 revolvers—potting away at clay pigeons or fast-moving paper targets with .45 ACP slugs.

Some U.S. pilots and observers were trained by the British. This British sergeant provides instruction on using the common ring-and-bead sights attached to a Lewis Gun. England, June 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Some U.S. pilots and observers were trained by the British. This British sergeant provides instruction on using the common ring-and-bead sights attached to a Lewis Gun. England, June 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

“The Spectacular Elements Of Air Combat”

In the U.S. Army’s detailed 1978 report, “The U.S. Air Service in World War I: The Final Report and a Tactical History” the unsung heroes of the first air war are succinctly described:

1918 has clearly demonstrated the fact that the work of the observer and observation pilot is the most important and far-reaching which an Air Service operating with an Army is called upon to perform.

The report goes on to say that the truth of the preceding statement was not even close to the general or public impression of the air war. In short, everyone seemed to be fascinated with the story of the Great War’s fighter aces, and the indispensable work of the observer/bomber crews was generally overlooked.

The spectacular elements of aerial combat, the featuring of successful pursuit pilots, and the color of romance which was attached to the work of men whose only business was to fight in the air, combined to create a popular idea of the importance of pursuit duty.

The Hythe Mark III gun camera was used to assess both observer and pilot gunnery skills. N.A.R.A. photograph.

The Hythe Mark III gun camera was used to assess both observer and pilot gunnery skills. N.A.R.A. photograph.

How many of us dreamed of being a successful fighter pilot? How few of us imagined becoming a bomber pilot or an observer sitting in the “back seat?” As it turns out, the observer’s job was complicated, difficult and dangerous—and as completely unglamorous as it was vitally important. Not only did the observer have to be able to read maps and plot artillery fire, he also had to be a capable photographer as well as a marksman who was completely familiar with his Lewis gun—shooting it and maintaining it. The Air Service report notes:

The large percentage of the men who failed to qualify for observer work is the result of two factors: the very high standard required for the modern observer, and the fact that it is impossible to instruct a student in this extremely technical and arduous duty unless he himself desires earnestly to serve in this capacity. In the last phase of the war the work of the observer was constantly becoming more diversified, more important, and more difficult.

Ongoing Training

As important as the stateside introduction to aerial gunnery was, combat experience proved to be the best teacher. Once American airmen reached France, they were in for more intensive training in a completely unforgiving environment—even after the men received their postings to combat squadrons, gunnery training continued during every available moment.

Learning the nuances of an aircraft machine gun: Aviation cadets at Princeton observe the workings of the Marlin aircraft machine gun. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Learning the nuances of an aircraft machine gun: Aviation cadets at Princeton observe the workings of the Marlin aircraft machine gun. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Changes in aircraft and firearms mounts brought on the need for updated training. Pursuit pilots transitioned from the nimble-but-fragile Nieuport 28, with two Vickers MGs mounted on the port side of the engine, to the fast and sturdy SPAD XIII, with its twin Vickers mounted directly in front of the pilot atop the engine.

For the observers, the availability of more Lewis guns meant more twin gun mounts, which provided more defensive firepower but created a much heavier rig for the gunner to maneuver inside his cramped position. Some gunners chose to fly with a single gun, feeling that it sped up their reaction time to fire on an incoming German fighter. The Air Service report comments on the value of accurate shooting, particularly in combat at a great height without a parachute:

The idea that a fighting airplane should be regarded mainly as a moving platform for a machine gun has been fully demonstrated, and it is hardly too much to say that the length of a pilot’s life at the front is directly proportional to his and his observer’s ability to shoot.

In the combat zone: Continued training kept veterans sharp and helped new men stay alive. Here an observer works out with a twin-Lewis mount, commonly found on the Breguet 14, Salmson 2 A.2, and DH-4 recon/bomber aircraft of the U.S. Army Air Service. Issoudon, France, summer 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

In the combat zone: Continued training kept veterans sharp and helped new men stay alive. Here an observer works out with a twin-Lewis mount, commonly found on the Breguet 14, Salmson 2 A.2, and DH-4 recon/bomber aircraft of the U.S. Army Air Service. Issoudon, France, summer 1918. N.A.R.A. photograph.

America’s “Ace of Aces” Lt. (later Capt.) Eddie Rickenbacker, of the 94th Aero Squadron. Rickenbacker stands by his first mount, a Nieuport 28—he scored the first six of his 26 victories in this type. Twin Vickers guns are mounted on the port side of the cockpit. N.A.R.A. photograph.

America’s “Ace of Aces” Lt. (later Capt.) Eddie Rickenbacker, of the 94th Aero Squadron. Rickenbacker stands by his first mount, a Nieuport 28—he scored the first six of his 26 victories in this type. Twin Vickers guns are mounted on the port side of the cockpit. N.A.R.A. photograph.

Vietnam War Equipment

Mike Thornton

Michael Thornton is a hardcore 30 year-veteran of the United States Navy, a founding member of SEAL Team Six, and one of only three SEALs to receive the Medal of Honor in ‘Nam – an honor he earned in blood on Halloween 1972, when he almost single-handedly battled through enemy territory against a swarming horde of enemy soldiers, charged through a naval artillery bombardment to save his commanding officer from certain death, and then swam three hours through North Vietnamese waters with two wounded guys hanging off his back and a half-dozen chunks of grenade shrapnel lodged in various parts of his abdomen.

If that’s not badass enough for you, then clearly you’ve come to the wrong website.

Mike Thornton was born March 23, 1949 in Greenville, South Carolina. He joined the U.S. Navy and served as a Gunner’s Mate on a couple destroyers, but in 1968 he decided to try his hand at making the Navy’s elite Underwater Demolitions Team – the original precursor to the SEALs. Training was brutal, exhausting, and unbelievably intense – of the 129 men who signed up for UDT Class 49, only 16 graduated and were accepted into the program.

One of those 16 was Mike Thornton. Not long after completing one of the most brutal military training courses on the face of the planet, he was assigned to SEAL Team One and deployed to the Republic of Vietnam at the height of the Vietnam War.

Thornton arrived in-country in 1969 and spent the next three years doing a wide variety of super-badass over-the-top Navy SEALs stuff. He gathered intel on enemy positions, scouted deep behind enemy lines on daring covert missions, captured prisoners when he could, battled enemy forces on the reg, and basically did all that cool Black Ops classified SEAL stuff that was presumably so hardcore and top-secret classified that we’ll likely never really know the full details of all of it.

Team One was at the heart of many of America’s Special Operations in ‘Nam, and in the fall of 1972 this was still very much the case. In October, 23 year-old Petty Officer Mike Thornton was sent on a mission to the Qua Viet Naval Base in Quan Tri Province on a dangerous mission to gather intel on some NVA positions, capture a few prisoners, and then somehow extract back to friendly lines. Thornton’s team would consist of himself, three South Vietnamese Special Forces operators, and the unit commander, Lieutenant Thomas Norris, a hardcore Medal of Honor recipient Navy SEAL who was already a legend among the SEALs thanks to a wild mission he’d undertaken a few months earlier when he went undercover deep into enemy territory to rescue a downed American pilot. Facing extreme danger, and surrounded constantly by a massive force of NVA soldiers, Norris succeeded in extracting not only the pilot, but also the crew of a team that had already gone in to get the pilot and ended up getting pinned down. The mission was so hardcore that they made a movie out of it – it’s called Bat*21, and Norris was so tough that they got Gene Hackman to play him in the movie.

Needless to say, this was not a crew of guys you wanted to face in a dark alley late at night.

The SEALs deployed first by sailing an ordinary-looking Vietnamese junk boat up a river late at night, then by boarding a small rubber boat and infiltrating enemy lines under the cover of darkness. Well, unfortunately, the mission started to go sideways right away – the map wasn’t really lining up with what was supposed to be there, and it didn’t take long for Norris and Thornton to realize that they’d landed a little too far into enemy terrirotyr. So now, instead of scouting temporary enemy fortifications that had been thrown up days before, these guys were now straight in the middle of a hardened network of NVA bunkers that had been designed years ago to repel full-scale assaults by massive formations of enemy troops and armor.

It wasn’t really the kind of place you wanted to be walking around with an American flag patch on your shoulder.

So, ok, the SEALs were off-course, and were now wayyyy deeper in enemy territory then they would have hoped, but a mission is a mission, and these guys were pros. They immediately went to work – noting bunker positions, troop concentrations, fortifications, vehicles, and radio towers. They Splinter Celled their way silently and stealthily through the heart of an enemy naval base first by boat, then on foot, collecting tons of valuable intel, all somehow without being detected by the hundreds of hardened veteran NVA troops that now surrounded them from every direction.

Then, over one particular ridgeline, the SEALs saw a couple of NVA guards standing nearby. They were far enough away from the main base that they could potentially have been grabbed and taken prisoner without alerting the base, so the SEAL team moved in to try and take them into custody. The two South Vietnamese SEALs grabbed one of the guys, but they weren’t quick enough to grab the second guy – that dude bolted for it and started screaming his damn head off for the NVA to sound the alarm.

Thornton ran him down and capped him with a well-placed pistol round, but it was already too late – the SEAL stopped dead in his tracks as he heard the sound of alarm sirens blaring from a nearby camp.

Thornton ran for it. By the time he’d reached the spot where his buddies were waiting for him, he was already being run down by a group of roughly fifty NVA soldiers, who immediately started spraying AK-47 gunfire into the jungle all around him.

One of the South Vietnamese SEALs launched a LAW rocket into the middle of the attacking forces, hoping that the resulting explosion would buy the SEAL team a little time to take off and run to the extraction point.

The SEALs were now in a fight for their lives. They had to get back to their extraction point before they were completely surrounded and overrun by a force that massively outnumbered them.

Fighting through the pitch darkness, facing down presumably hundreds of enemy soldiers, the five Navy SEALs fought the way you’d expect the most badass military force in the world to fight. They fired, repositioned, fired again, and launched grenades and LAW rockets, constantly changing position in an attempt to confuse the enemy about how many guys they were facing. The SEALs had the advantage of surprise, and concealment, and the NVA couldn’t just charge in there after them because they couldn’t quite figure out how many guys they were actually facing. So, through the darkness of the Vietnamese jungle, the Navy SEALs spent the next four hours (!!) battling their way back towards the water.

Bullets were zipping through the jungle from every direction as the SEALs made their escape. Five men against hundreds. As his ammunition began to run out, Norris (who took up the rear of the SEAL position) ditched his M-16 and took an AK-47 off a dead enemy soldier, using captured ammo to keep up a steady hail of fire back towards the ever-closing NVA troops. At the head of the column, Mike Thornton raced through pitch-black jungle navigating his team to the extract point. As dawn began to break and the SEALs approached the beach, Norris got on his radio and called in for two Destroyers to come in and lay down some covering fire. Shortly after, though, he received a report that heavy fire from fortified NVA shore guns had damaged both Destroyers and drove them back from the coast. A cruiser was inbound to help, but for now the SEALs were on their own.

Thornton continued to the extraction, firing his M-16 in all directions, until suddenly an enemy grenade landed dangerously close to him. It exploded, ripping shrapnel through the SEAL. White-hot shards of splintered steel embedded in his back in six different places, as the concussive force of the blast sent him flying hard into the ground. With his ears ringing, and his back screaming in pain, Thornton still held on to his weapon, and rolled over onto his back just in time to see four NVA troops running up onto the ridgeline to finish the job – despite every muscle in his body screaming in pain, Thornton still somehow had the calmness and unimaginable skill to take out all four of those guys before they could spray him full of 7.62.

One of the South Vietnamese SEALs rushed over to pick Thornton up, and the SEAL asked what had happened to Tom Norris. The SEAL responded, “He’s gone. Let’s go”. The guy said that Norris’s position had been overrun, he was shot in the head and killed, and the rest of the team had to fall back. He urged Thornton to get to the beach to extract, because the window to get out of this alive was very rapidly closing, and a US Cruiser was already maneuvering into position to lay down some cover fire.

But Navy SEALs don’t leave a man behind. And Thornton wasn’t about to start now.

With AK-47 fire zipping around him from every direction, Michael Thornton ran 400 yards through a hail of bullets to reach the body of his good friend. Four NVA troops were standing over the fallen SEAL, but Thornton killed them with his rifle, screaming with rage, and finally fell to his knees at his friend’s side. Norris was bleeding badly from a gunshot to the head, but Thornton wasn’t about to leave that guy behind. With enemy troops ripping shots past his head, and blood pouring from grenade wounds in his back, Mike Thornton threw Tom Norris on his shoulders and started to make a run back for the beach.

It was at this point that the U.S. Navy cruiser reached firing position. And the coordinates the firing teams had were the ones that Tom Norris had given them – at a time when Norris thought he wasn’t going to get out of this fight alive.

The shell landed pretty much right where Norris’s body had been. The explosion blew Thornton 20 feet through the air, slamming him hard to the beach, ringing his ears, and blurring his vision. As he lie on the ground, he heard something amazing. A familiar voice, quiet and fading, but clearly audible even among the gunfire and artillery.

“Mike, buddy.”

Tom Norris was alive.

Surging with adrenaline, Mike Thornton jumped back to his feet, threw Norris on his back, and started running to the shore. With bullets, mortars, and naval artillery chewing up the beach and the trees around him, Thornton ran though the fire, finally reaching the shore, where one of the Vietnamese SEALs also lay wounded from a gunshot to the back.

Thornton grabbed that guy too. Then he jumped in the water, inflated his life vest, and proceeded to swim through salt water with six grenade wounds in his back for four hours while dragging two seriously wounded men.

The American ship that had been sent to extract the SEALs was preparing to go home, convinced that nobody could have survived that mission, when suddenly they saw a dude in the water shooting his rifle in the air trying to get their attention. It was Mike Thornton.

Every member of the mission survived.

When Thornton received his Medal of Honor in 1973, Tom Norris was still recovering in the hospital, and they weren’t about to let him leave just to attend a medal ceremony. So, the day of the ceremony, Thornton went to the hospital, put Norris in a wheelchair, and snuck him out the back door so he could attend.

After Vietnam, Mike Thornton would go on to be a BUD/S instructor in Coronado, where he would train future Navy SEALs, as well as members of the British Royal Marines’ badass Special Boat Service. He was a founding member of SEAL Team Six in 1980, and retired as a Lieutenant in 1992. Nowadays there’s a really badass statue of his rescue mission standing outside the SEAL museum in Ft. Pierce, Florida.

Links:

Mike-Thornton.com

NavySEALs.com

Achievement.org

Defense Media Network

Wikipedia

Suggested Reading:

Collier, Peter and Nick Del Calzo. Medal of Honor. New York: Artisan, 2006.

Dockery, Kevin. SEALs in Action. New York: Avon Books, 1991.

Norris, Tom and Mike Thornton. By Honor Bound. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2016.

One reason the M203 was replaced by the M320 was the loading method.

The M320 swings to the side to open, as seen here:-

The M203 slides the launcher forward to load, which limits the length of any grenades you can load into it.

The variation in grenade length can be seen here:-

The shortest “standard” round would be easy to load into a M203, the longer pair would be manageable (about the size of some smoke/flare rounds) and the longest – looks like a fragmentation grenade with longer payload section – wou

- In 1935, lava from Hawaii’s Mauna Loa volcano threatened the nearby town of Hilo.

- Responding to a request by island volcanologists, the U.S. Army Air Service sent planes to bomb the lava flow.

- Although the scientist who requested the air strike thought it was a success, others weren’t so sure.

One of the U.S. Air Force’s oddest missions was against perhaps its most formidable adversary ever: Mother Nature.

In 1935, lava from the Mauna Loa volcano threatened the nearby seaside town of Hilo, Hawaii. So U.S. bombers, commanded by none other than future Gen. George S. Patton, bombed the lava flow in an attempt to save the town.

Experts were divided on how useful the air strikes ultimately were, but the bombs weren’t the last ones dropped to prevent natural disasters.

The Hawaiian islands are well known for volcanic activity; the islands themselves were formed by volcanic action over the course of millions of years. The “Big Island” of Hawaii is the home of Mauna Loa, one of the most active volcanoes in the world. It has erupted 33 times since 1843, often adding new territory to America’s 50th state. Indeed, Hawaii is probably the only state in the union that is continuously growing, thanks to volcanoes.

Mauna Loa’s lava flows are closely monitored, but typically harmless. One exception, however, was the 1935 eruption, which unexpectedly flowed north. The eruption started on November 21 and oozed at a rate of a mile a day toward the headwaters of the Wailuku River—the water supply for the town of Hilo. If the volcano cut the supply of fresh water to the town of approximately 20,000 people, the result could be catastrophic.

Thomas Jagger, the founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, appealed to the U.S. Army for help. Jagger wanted the Army Air Service, forerunner of the wartime Army Air Corps and later the U.S. Air Force, to bomb the lava tubes and channels that fed lava in the direction of the river. Nobody thought American bombers could destroy the lava, but they hoped the bombing would divert the flow to another, non-threatening direction.

The mission was assigned to Army Air Service planes based on the island of Oahu and planned by Patton. The commander of the First Provisional Tank Brigade in World War I would of course later go on to command the Third Army in Europe during World War II.

The Hush Kit describes the air strike:

On December 27, 1935, ten Keystone B-3 and B-4 bombers from Luke Field on Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor flew the 200-odd miles to bomb the Humu‘ula lava flow. The bombers dropped 40 bombs, half were high explosive and the rest were WP smoke bombs to mark the impact points. Of the twenty high explosive bombs dropped, sixteen hit the target area and twelve hit the lava tunnel in question.

Here’s video of the planes involved in the air strike:

Jagger observed the air strike from a telescope at the base of Hawaii’s other volcano, Mauna Kea. “The experiment could not have been more successful; the results were exactly as anticipated,” he later told the New York Times. The lava slowed from covering more than 5,000 feet a day to 1,000 feet after the bombing, and the flow stopped entirely on January 2, 1936.

Not everyone shared Jagger’s optimism. Harold Stearns, a U.S. Geologic Survey who flew on the mission, believed the slowing and stopping of the flow was a coincidence. Jagger’s boss, the head of Hawaii National Park, told the Army the day after the attack, “Though we are as yet unable to determine what effect the airplane bombardment achieved … I feel very doubtful that it will succeed in diverting the flow.”

The U.S. Geologic Survey, writing about the incident more than 80 years later, says, “Modern thinking mostly supports Stearns’ conclusion.”

In 2015, the 23rd Bomb Squadron, the unit that flew the mission against Mauna Loa’s lava flow, returned to Hawaii to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the mission. A B-52 bomber assigned to the 23rd Expeditionary Bomb Squadron flew from its temporary base on the island of Guam to Hawaii, a 12-hour mission. The squadron insignia, this Air Force Global Strike Command article notes, still depicts bombs tumbling down onto a volcano.

The 1935 volcano air strike wasn’t the last time mankind trained its weapons of war on nature. Today, Russia and China occasionally send their air forces to bomb frozen rivers, typically to remove dangerously high levels of ice buildup or to allow nearby communities to reconnect with the outside world. And in July 2018, the Swedish Air Force bombed a wildfire on a military training ground, snuffing it out and preventing it from detonating unexploded munitions.

———————————————————————————– I for one did not know this. That and the man did get around did’nt he? All in all I have to say that the US Taxpayer got themselves a real bargain when they commissioned him into the Army.

Private Daniels was just not cut out to be a soldier. A wheeled vehicle mechanic, she was forever in trouble. She stole money from her roommate and then attacked the young lady with a shoe brush for reporting her. At the time of this incident she was already being put out of the Army for writing bad checks.

Private Daniels’ boyfriend was a local civilian whom she had met in a bar. I have no idea what he did or where he came from. She had invited him up to her room in the barracks, and he was stupid enough to accept.

CW2 Johansen was one of my Warrant Officers. A former NCO before attending the Warrant Officer course and flight training, Bill was an old school soldier. This fateful evening he was the Battalion Staff Duty Officer. Part of his responsibility involved circling through the barracks, the hangars and the motor pools to ensure everything was quiet and secure. Most officers, myself included, did a fairly cursory job of this. We weren’t at war, and the possibility that the Russians might try to infiltrate our truck park seemed low. Not so Bill Johansen. He checked everything quite thoroughly.

It was wintertime and well below freezing. Bill linked up with the CQ (Charge of Quarters) of the female barracks for a quick walk-through. (Barracks were segregated by gender back then.) The CQ was a junior enlisted soldier whose duty it was to mind the front desk to the barracks all night. As it was a female-only facility, the CQ served as Bill’s escort as he did his walk-through. On the second floor, as they strolled past the communal latrine, they heard jungle noises.

Bill dispatched the CQ to investigate. The CQ duly reported that Private Daniels and her boyfriend were enjoying a cozy shower together. Bill Johansen was having none of that.

Bill was a pretty intimidating guy. He snatched up Private Daniels’ terrified boyfriend and frog marched him, dripping and naked, down to the CQ desk. The poor kid asked if he could go back to Private Daniels’ room to retrieve his clothes, but Bill refused. He felt this to be a teachable moment.

The boyfriend was soaking wet. Bill had the CQ fetch whatever clothing was available in the latrine for the guy to use to cover himself. The CQ returned with Private Daniels’ see-through pink negligee.

Imagine if you will a 19-year-old wet, terrified man shivering in an office wearing nothing but a woman’s sexy transparent nightgown. With this as a foundation, Bill went to work. He started the conversation by postulating how long he thought the kid would go to jail for molesting government property.

Bill explained that Private Daniels belonged to the government, and that the penalties for illicit showering with GIs were severe. By the time he got done the unfortunate young man was expecting fifteen to twenty years hard labor at Fort Leavenworth. At that critical moment Bill placed a phone call. When he returned to the holding area the damp naked man was nowhere to be found.

The kid had crawled out the window. It was 26 degrees out, and Private Daniels’ date was both soaked and barefoot. Additionally, ours was an absolutely enormous Army post. It was literally miles to the nearest gate. Bill sighed and rang up the MPs. He asked them to be on the lookout for a desperate, shivering, wet naked man trying to escape and evade off post. They dispatched a squad car and found the poor miserable guy in short order.

The MPs gave the kid a ride to his apartment off post and donated an Army blanket to the cause. Though I can’t be sure, I rather suspect the sordid events of the evening put a damper on the blossoming relationship between Private Daniels and her now exceptionally clean boyfriend.

Bill briefed me up on the situation the following day. I didn’t have the heart to castigate Private Daniels. She was already well on her way to becoming a civilian. Sharing a communal shower with a civilian in the female barracks wasn’t going to substantially accelerate that process.

I don’t know exactly what I expected work to be like when I chose to become an Army officer. I hoped for travel and adventure, to be sure, but I never expected stuff like that. As for Bill Johansen, he felt good about himself. He could rest easy in the knowledge that absolutely all of the Battalion property was indeed secure.

In June 1859, while attempting to climb a sloping bare rock in southwest Texas, one of the Army’s camels lost its footing and fell, smashing one of the precious water barrels it was carrying. An officer accompanying the expedition quickly cut the lines ensnaring the camel, preventing a bad situation from becoming worse. (Camels in Texas, by Thomas Lovell, courtesy of the Abell-Hanger Foundation and the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum, Library and Hall of Fame of Midland, Texas, where the painting is on permanent display.)

In June 1859, while attempting to climb a sloping bare rock in southwest Texas, one of the Army’s camels lost its footing and fell, smashing one of the precious water barrels it was carrying. An officer accompanying the expedition quickly cut the lines ensnaring the camel, preventing a bad situation from becoming worse. (Camels in Texas, by Thomas Lovell, courtesy of the Abell-Hanger Foundation and the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum, Library and Hall of Fame of Midland, Texas, where the painting is on permanent display.)In the 1830s America’s westward expansion was being severely curtailed by the inhospitable terrain and climate faced by pioneers and settlers. This was particularly the case in the southwest, where arid deserts, mountain peaks and impassable rivers were proving to be an almost insurmountable obstacle to men and animals alike. In 1836, U.S. Army LT George H. Crosman hit upon an unusual idea to deal with the situation. With the able assistance of a friend, E. H. Miller, Crosman made a study of the problem and sent a report on their findings to Washington suggesting that:

“For strength in carrying burdens, for patient endurance of labor, and privation of food, water & rest, and in some respects speed also, the camel and dromedary (as the Arabian camel is called) are unrivaled among animals. The ordinary loads for camels are from seven to nine hundred pounds each, and with these they can travel from thirty to forty miles a day, for many days in succession. They will go without water, and with but little food, for six or eight days, or it is said even longer. Their feet are alike well suited for traversing grassy or sandy plains, or rough, rocky hills and paths, and they require no shoeing… “

Their report was disregarded by the War Department. It was with this rather simple suggestion, however, that Crosman first introduced the concept for what would later become the most unique experiment in U.S. Army history.

MAJ Henry C. Wayne, an officer in the Quartermaster Department, was one of the early advocates for the Army’s use of camels. He resigned from the Army on 31 December 1860 and was later commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. (Library of Congress)

MAJ Henry C. Wayne, an officer in the Quartermaster Department, was one of the early advocates for the Army’s use of camels. He resigned from the Army on 31 December 1860 and was later commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. (Library of Congress)The idea lay dormant for several years until 1847 when Crosman, now a major, met MAJ Henry C. Wayne of the Quartermaster Department, another camel enthusiast, who would take up the idea. MAJ Wayne submitted a report to the War Department and Congress recommending the U.S. government’s importation of camels. In so doing, he caught the attention of Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, who thought Wayne’s suggestions both practical and worthy of attention. Davis, as chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, tried for several years to acquire approval and funding for the project, but to no avail. It was not until 1853, when Davis was appointed Secretary of War, that he was able to present the idea of importing camels to both President Franklin Pierce and a still skeptical Congress.

In his annual report in 1854, Davis informed Congress that, in the “…. Department of the Pacific the means of transportation have, in some instances, been improved, and it is hoped further developments and improvements will still diminish this large item of our army expenditure. In this connexion, … I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of camels and dromedaries for military and other purposes, and for reasons set forth in my last annual report, recommend that an appropriation be made to introduce a small number of the several varieties of this animal, to test their adaptation to our country…”

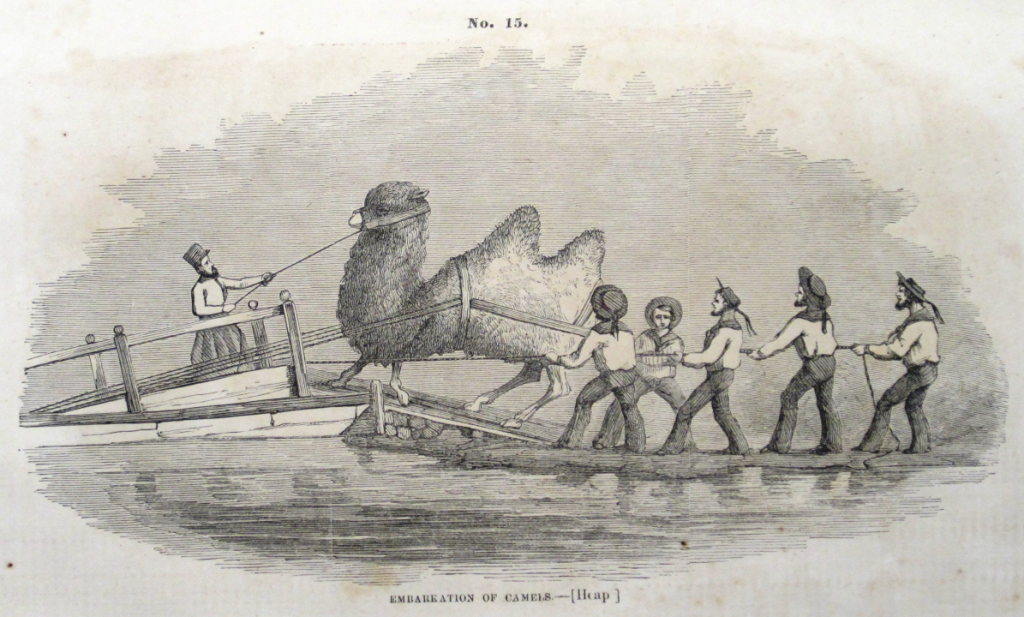

On 3 March 1855, Congress agreed and passed the Shield amendment to the appropriation bill, resolving: “And be it further enacted, that the sum of $30,000 be, and the same is hereby appropriated under the direction of the War Department in the purchase and importation of camels and dromedaries to be employed for military purposes.” Secretary Davis would finally get his camels.

Davis lost no time in getting the experiment underway. In May 1855, he appointed Wayne to head the expedition to acquire the camels. The Navy store ship USS Supply, was provided by the Navy to transport the camels to the United States. The Supply was under the command of LT David Dixon Porter, who, on being informed of the mission and its cargo, saw to it that she was outfitted with special hatches, stable areas, a “camel car,” and hoists and slings to load and transport the animals in relative comfort and safety during their long voyage.

Sailors and an Arab camel herder load a Bactrian camel aboard the USS Supply during one of the two expeditions to procure camels. (National Archives)

Sailors and an Arab camel herder load a Bactrian camel aboard the USS Supply during one of the two expeditions to procure camels. (National Archives)When Wayne inspected the Supply, he was both amazed and greatly impressed with Porter’s meticulous and thorough preparations. It was decided that while Wayne went to London and Paris to visit the zoos and interview military men and scientists with first-hand knowledge and experience in camel handling, Porter would sail the Supply to the Mediterranean and deliver supplies to the U.S. naval squadron based there. On 24 July, Wayne joined Porter in Spezzia (La Spezia), Italy and from there they sailed to the Levant, arriving at Goletta (La Goulette) in the Gulf of Tunis on 4 August.

In Goletta, the expedition purchased their first three camels, two of which they later discovered were infected with the “itch,” a form of mange. Arriving in Tunis they were joined by Mr. Gwynne Harris Heap, a brother-in-law of Porter’s, whose father had been U.S. Consul at Tunis. Heap was familiar with eastern languages and customs and his extensive knowledge of camels proved an invaluable asset to the expedition. During the next five months the expedition sailed across the Mediterranean, stopping at Malta, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. Wayne, Porter, and Heap also made a separate voyage on their own to the Crimea to speak with British officers about their use of camels during the Crimean War. A similar side trip was made to Cairo while the Supply was docked at Alexandria.

Jefferson Davis first encouraged the Army’s use of camels while serving in the U.S. Senate. In 1855, Secretary of War Davis persuaded a skeptical Congress to appropriate $30,000 for the purchase and importation of camels for the Army. (Jefferson Davis, by Daniel Huntington, Army Art Collection)

Jefferson Davis first encouraged the Army’s use of camels while serving in the U.S. Senate. In 1855, Secretary of War Davis persuaded a skeptical Congress to appropriate $30,000 for the purchase and importation of camels for the Army. (Jefferson Davis, by Daniel Huntington, Army Art Collection)After numerous difficulties involving a lack of suitable animals and obtaining export permits, the expedition finally acquired through purchase and as gifts a sufficient number of camels. In all, they obtained thirty-three animals: nineteen females and fourteen males. The thirty-three specimens included two Bactrian (two-humped), nineteen dromedaries (one-humped), nineteen Arabian, one Tunis burden, one Arabian calf, and one Tuili or booghdee camels. The Arabian dromedaries are renowned for their swiftness and the Bactrians for their strength and burden carrying abilities. Thanks to Heap’s knowledge of camels and his negotiating skills, the cost averaged around $250 per animal, and most were in good condition. The expedition also hired five natives–Arabs and Turks–to help care for the animals during the voyage and act as drovers when they reached America. On 15 February 1856, with the animals safely loaded aboard, the expedition began its voyage home.

The expedition, slowed by storms and heavy gales, lasted nearly three months. It was Porter’s foresight and diligence in caring for the animals that enabled them to survive the horrendous weather conditions. The Supply finally unloaded its cargo on 14 May at Indianola, Texas. During the voyage one male camel had died, but six calves were born, of which two had survived the trip. The expedition therefore landed with a total of thirty-four camels, all of whom were in better health than when they left their native soil.

On 4 June, after allowing the camels some needed rest and a chance to acclimatize themselves, Wayne marched the herd 120 miles to San Antonio, arriving on 18 June. Wayne planned to establish a ranch and provide facilities for breeding the camels, but Secretary Davis had other ideas, stating, “the establishment of a breeding farm did not enter into the plans of the department. The object at present is to ascertain whether the animal is adapted to military service, and can be economically and usefully employed therein.” Despite his objections, Davis did see the advantages in sending Porter on a second trip to secure more camels. There was over half of the appropriation money remaining and the Supply was still on loan from the Navy. On Davis’ instructions, Porter once again left for Egypt. On 26-27 August, Wayne moved the herd some sixty miles northwest to Camp Verde, a more suitable location for his caravansary. He constructed a camel corral (khan) exactly like those found in Egypt and Turkey. Camp Verde would be the “corps” home for many years.

To satisfy Davis’ concerns about the military usefulness of the camels, Wayne devised a small field test. He sent three wagons, each with a six-mule team, and six camels to San Antonio for a supply of oats. The mule drawn wagons, each carrying 1,800 pounds of oats, took nearly five days to make the return trip to camp. The six camels carried 3,648 pounds of oats and made the trip in two days, clearly demonstrating both their carrying ability and their speed. Several other tests served to confirm the transporting abilities of the camels and their superiority over horses and mules. Davis was much pleased with the results and stated in his annual report for 1857, “These tests fully realize the anticipation entertained of their usefulness in the transportation of military supplies…. Thus far the result is as favorable as the most sanguine could have hoped.”

Over the next several months, Wayne worked with the civilian drovers and soldiers to accustom them to the camels and vice versa. They learned how to care for and feed the animals, manage the cumbersome camel saddles, properly pack the animals and, most importantly, how to deal with the camel’s mannerisms and temperament. By nature the camel is a docile animal, but can demonstrate a violent, aggressive temper when abused or mistreated, literally kicking, biting or stomping an antagonist to death. Camels, like cows, chew a type of cud and when annoyed would often spit a large, gelatinous, foul smelling mass of cud at its detractor. The most difficult aspect for the men to get used to was the camel’s somewhat pungent smell. Although camels really do not smell any worse than horses, mules or unwashed men, their smell was different and had a tendency to frighten horses unfamiliar with the odor.

On 30 January 1857, Porter returned to the U.S. with an additional forty-one camels. Since by this time five of the original heard had died from disease, the new arrivals brought the total number of camels to seventy. The animals were landed at Indianola on 10 February and then moved to Camp Verde.

In March 1857, James Buchanan became president and several changes were made which directly affected the camel experiment. John B. Floyd replaced Davis as Secretary of War and MAJ Wayne was transferred back to the Quartermaster Department in Washington, DC, thus removing in one blow two of the camel experiment’s main supporters. Nevertheless, Secretary Floyd decided to continue his predecessor’s experiment.

In response to a petition made by some 60,000 citizens for a permanent roadway which would help link the eastern territories with those of the far west, Congress authorized a contract to survey and build a wagon road along the thirty-fifth parallel from Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory, to the Colorado River on the California/Arizona border. The contract was won by Mr. Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a former Superintendent of Indian Affairs for California and Nevada who held the rank of brigadier general in the California militia. Beale was a good choice for the survey, having traveled parts of this region during the Mexican War and while surveying a route for a transcontinental railway.

It was only after Beale accepted the contract that he learned of the Secretary of War’s special conditions. Floyd ordered Beale to take twenty-five of the camels with him on the surveying expedition. Beale protested vehemently at being encumbered with the camels, but Floyd was adamant. Since Wayne had left Camp Verde, the camels had been unused. The government had gone to some time and expense to test the camels in just this kind of situation and Floyd was determined to see if they would justify the money being spent on them. Although strongly opposed to the idea, Beale finally consented.

On 25 June 1857, the surveying expedition departed for Fort Defiance. The party consisted of twenty-five camels, two drovers, forty-four soldiers, twelve wagons, and some ninety-five dogs, horses and mules. At first, the performance of the camels convinced Beale that his original protests were well founded, as the animals moved slower than the horses and mules and were usually hours late reaching camp. On the second week of the journey, however, Beale changed his tune and noted that the camels were “walking up better.” He later attributed the camel’s slow start to their months of idleness and ease at Camp Verde. It was not long after that the camel’s settled to their task and began outdistancing both horses and mules, packing a 700 pound load at a steady speed and traversing ground that caused the other animals to balk. By the time the expedition arrive at Fort Defiance in early August, Beale was convinced of the camel’s abilities. On 24 July he wrote to Floyd, “It gives me great pleasure to report the entire success of the expedition with the camels so far as I have tried it. Laboring under all the disadvantages ….we have arrived here without an accident and although we have used the camels every day with heavy packs, have fewer sore backs and disabled ones by far than would have been the case travelling with pack mules. On starting I packed nearly seven hundred pounds on each camel, which I fear was too heavy a burden for the commencement of so long a journey; they, however, packed it daily until that weight was reduced by our diurnal use of it as forage for our mules.”

Upon finding water, horses on a surveying expedition eagerly quench their thirst while the accompanying camels show little interest. The Army’s camels proved they could withstand the oppressive climate of the American Southwest and other hardships that could send horses and mules into a panic. (Horses Quenching Their Thirst, Camels Disdaining, by Ernest Etienne de Franchville Narjot, The Stephen Decatur House Museum)

Upon finding water, horses on a surveying expedition eagerly quench their thirst while the accompanying camels show little interest. The Army’s camels proved they could withstand the oppressive climate of the American Southwest and other hardships that could send horses and mules into a panic. (Horses Quenching Their Thirst, Camels Disdaining, by Ernest Etienne de Franchville Narjot, The Stephen Decatur House Museum)At the end of August the expedition left the fort on their survey. Beale was concerned about the dangers inherent in such a journey over such treacherous terrain, but these concerns proved unfounded in regard to the camels. “Sometimes we forget they are with us. Certainly there never was anything so patient or enduring and so little troublesome as this noble animal. They pack their heavy load of corn, of which they never taste a grain; put up with any food offered them without complaint, and are always up with the wagons, and, withal, so perfectly docile and quiet that they are the admiration of the whole camp. ….(A)t this time there is not a man in camp who is not delighted with them. They are better today than when we left Camp Verde with them; especially since our men have learned, by experience, the best mode of packing them.”

The camels ate little of the forage, content instead to eat the scrub and prickly plants found along the trail. They could travel thirty to forty miles a day, go for eight to ten days without water and seemed not the slightest bit bothered by the oppressive climate. At one point the expedition became lost and was mistakenly led into an impassable canyon. The ensuing lack of grass and water for over thirty-six hours made the mules frantic. A small scouting party mounted on camels was sent out to find a trail. They found a river some twenty miles distant and led the expedition to it, literally saving the lives of both men and beasts. From then on, the camels were used to find all watering holes.

The expedition reached the Colorado River on 17 October, the last obstacle in their journey. While preparing to cross the river, Beale wrote to Floyd on the 18 October, “An important part of all of our operations has been acted by the camels. Without the aid of this noble and useful brute, many hardships which we have been spared would have fallen to our lot; and our admiration for them has increased day by day, as some new hardship, endured patiently, more fully developed their entire adaptation and usefulness in the exploration of the wilderness. At times I have thought it impossible they could stand the test to which they have been put, but they seem to have risen equal to every trial and to have come off of every exploration with as much strength as before starting…. I have subjected them to trials which no other animal could possibly have endured; and yet I have arrived here not only without the loss of a camel, but they are admitted by those who saw them in Texas to be in as good a condition as when we left San Antonio…. I believe at this time I may speak for every man in our party, when I say that there is not one of them who would not prefer the most indifferent of our camels to four of our best mules.”

On 19 October, as the expedition began to cross the Colorado, Beale was concerned about the camels getting across as he had been told they couldn’t swim. He was pleasantly surprised when the largest camel was led to the river, plunged right in fully loaded and swam across with no difficulty. The remaining camels also crossed without incident, but two horses and ten mules drowned in the attempt. Their surveying mission completed, Beale led the expedition to Fort Tejon, about 100 miles north of Los Angeles, to rest and re-provision. The expedition had lasted nearly four months and covered over twelve hundred miles.

Floyd was extremely pleased with the results. He ordered Beale to bring the camels back to Camp Verde, but Beale demurred, giving the excuse that if the troops in California became involved in the “Mormon War,” the camels would prove invaluable carrying supplies. Instead, Beale moved the camels to the ranch of his business partner, Samuel A. Bishop, in the lower San Joaquin Valley. Bishop used the camels in his personal business, hauling freight to his ranch and the new town arising near Fort Tejon. During one such venture, Bishop and his men were threatened with attack by a large band of Mohave Indians. Bishop mounted his men on the camels and charged, routing the Indians. It was the only combat action using the camels and it was performed not by the U.S. Army, but by civilians.

In April 1858, Beale was ordered to survey a second route along the thirty-fifth parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas to the Colorado River for use as a wagon road and stage line He was given the use of another twenty-five camels from Camp Verde for this expedition. It took Beale nearly a year to complete this mission and his report to Floyd again extolled the exemplary performance of the camels.

In his annual report to Congress in December 1858, Floyd enthusiastically stated, “The entire adaptation of camels to military operations on the plains may now be taken as demonstrated.” He further declared that the camel had proven its “great usefulness and superiority over the horse for all movements upon the plains or deserts” and recommended that Congress “authorize the purchase of 1,000 camels.” Congress, however, was not convinced and authorized no further funding. Undeterred, Floyd pleaded his case again in his annual report in 1859, “The experiments thus far made – and they are pretty full – demonstrate that camels constitute a most useful and economic means of transportation for men and supplies through the great desert and barren portions of our interior… An abundant supply of these animals would enable our Army to give greater and prompter protection to our frontiers and to all our interoceanic routes than three times their cost expended in another way. As a measure of economy I can not too strongly recommend the purchase of a full supply to the consideration of Congress.” Despite the abundant evidence and sound arguments Congress wouldn’t budge. Floyd tried again in 1860, but by then the clouds of civil war had Congress’ undivided attention and the idea of purchasing camels was far from their minds.

In November 1859, the Army took charge of the twenty-eight camels on Bishop’s farm and moved them to Fort Tejon. Although the animals were in rather poor physical shape, there were now three more than Beale had originally left on the ranch, demonstrating MAJ Wayne’s theory that the camels – if given the opportunity – could breed on their own. This herd remained at Fort Tejon until March 1860, when they were relocated to a rented grazing area some twelve miles from the fort. In September several camels were sent to Los Angeles to take part in the Army’s first official test of camels in California.

The test, under the command of the Assistant Quartermaster, CPT Winfield Scott Hancock, was to see if the camels could effectively be used as an express service. The camels were tested against the existing service, a two-mule buckboard, in carrying messages some three hundred miles from Camp Fitzgerald to Camp Mohave on the Colorado River. Two test runs were made and, in both, the camels died from exhaustion, leading the Army to realize what other tests had already shown, that camels were not bred for speed but for transport. Although the test proved that the “camel express” was significantly cheaper, it was no faster than the mule and buckboard service and was much harder on the camels. This was the only test they had ever failed.

A second Army experiment was run in early 1861 when four camels were assigned to accompany the Boundary Commission on their surveying expedition of the California-Nevada boundary. The expedition, hopelessly disorganized from the start, was a complete failure and nearly ended in disaster. The expedition got lost and wandered into the merciless Mojave Desert. After losing several mules and abandoning most of their equipment, it was the steadfast camels that saved the day and led the survivors to safety.

The advent of the Civil War effectively halted the camel experiment. Rebel troops occupied Camp Verde on 28 February 1861 and captured several of the remaining camels, using them to transport salt and carry mail around San Antonio. The camels suffered greatly at the hands of their captors, who had an intense dislike for the animals. They were badly mistreated, abused and a few of them were deliberately killed.

The herd near Fort Tejon, numbering thirty-one camels, was transferred to the Los Angeles Quartermaster Depot on 17 June 1861. During the next three years the camels were kept well fed and continued to breed, frequently being transferred from post to post as no one knew what else to do with them. Several recommendations to use them for mail service were proposed, but never adopted. The expense of feeding and caring for the unused animals finally became too much and, on the recommendation of the Department of the Pacific, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered them to be sold at public auction. Apparently unaware of the numerous successful tests performed with the camels, Stanton stated, “I cannot ascertain that these have ever been so employed as to be of any advantage to the Military Service, and I do not think that it will be practical to make them useful.”

On 26 February 1864, the thirty-seven camels from California were sold for $1,945, or $52.56 per camel. The surviving forty-four camels from Camp Verde were finally recovered at the end of the war. On 6 March 1866, they too were put on the auction block, bringing $1,364, or $31 per camel. The Army’s Quartermaster-General, MG Montgomery Meigs, approved the sale, stating his hopes that civilian enterprises might more successfully develop use of the camel and expressing his sincere regrets that the experiment had ended in failure.

The camels ended up in circuses, giving rides to children, running in “camel races,” living on private ranches, or working as pack animals for miners and prospectors. They became a familiar sight in California, the Southwest, Northwest, and even as far away as British Columbia, their strange appearance often drawing crowds of curious people. In 1885, as a young boy of five living at Fort Seldon, New Mexico, GEN Douglas MacArthur recalled seeing a camel: “One day a curious and frightening animal with a blobbish head, long and curving neck, and shambling legs, moseyed around the garrison…. the animal was one of the old army camels.”

Eventually, when the curiosity wore off or their new owners simply did not want or need them anymore, many of the camels were turned loose in the wild to fend for themselves. They were seen for many years afterward, wandering the deserts and plains of the Southwest. The last of the original Army camels, Topsy, was reported to have died in April 1934, at Griffith Park, Los Angeles, at the age of eighty, but accounts of camel sightings continued for decades. Although never officially designated, “U.S. Army Camel Corps,” this is how the Army’s camel experiment has been remembered. Ignored and abandoned, it was an ignominious and unfortunate end for these noble “ships of the desert.”