Category: The Green Machine

THE UNSINKABLE BATTLESHIP OF MANILA BAY

Warship Wednesday, May 6, 2015: The unsinkable battleship of Manila Bay

Here we see the concrete battleship, Fort Drum, as she appeared before 1941. While yes, this is not a ship but a U.S. Army coastal defense fortification, it has all the aspects of a ship above the waterline!

When Dewey swept into Manila Bay in 1898, the battle that his Asiatic Squadron gave the outgunned Spanish fleet was brief and historic– leaving the U.S. with de facto control of the island chain (or at least the Bay) that was made official after the war ended. After the Japanese defeat of the Russian Pacific Fleets (both of them) in 1905– during which a number of the Tsar’s ships took refuge in Manila Bay under the watchful eye of the USN, it became a priority to beef up the defenses around the harbor to keep the Navy there from turning into another Port Arthur.

In the mouth of the Bay was El Fraile Island, a small slip of rock that the Army, in charge of Coastal Defense, decided to place a mine-control battery atop. However, this plan soon changed and the Army, with the Navy’s blessing, went about building their own static battleship.

Under the plan of Lt. John Kingman of the Army Corps of Engineers, the military leveled off El Fraile starting in 1909 and encased the entire island in steel-reinforced concrete with an average depth of 36-feet thick along the walls.

Several stories deep, a fort was constructed that included water cisterns, fuel tanks to run electrical generators, barracks for artillerymen, dining facilities, and storage for enough food to last the defenders months if needed.

Powder magazines and “navy-type” electrical passing scuttles. Drum could stock 440 shells for its main batteries. Click to big up

Atop the roof of the structure, which itself was 20-feet thick, were mounted a pair of M1909 turrets that each houses a pair of 14-inch (360mm) guns. Although a Navy-style mount, it was all-Army and contained unique wire-wound guns modified from the standard M1907 big guns mounted in coastal defense forts stateside.

While the standard CONUS 14-inchers were “disappearing” mounts, these larger 40-caliber tubes, with their 46-foot length, allowed the 1,209-pound AP shells to fire out to some 22,705-yards. To protect these turrets (named Batteries Marshall and Wilson), they had 16-inches of steel armor on their face, 14 on the sides and rear, and 6 on the roof. Of course, these giant turrets, with their outsized guns, tipped the scales at 1,160-tons or about the weight of a standard destroyer of the era, but hey, it’s not like they were going to sink the island or anything.

While the standard CONUS 14-inchers were “disappearing” mounts, these larger 40-caliber tubes, with their 46-foot length, allowed the 1,209-pound AP shells to fire out to some 22,705-yards. To protect these turrets (named Batteries Marshall and Wilson), they had 16-inches of steel armor on their face, 14 on the sides and rear, and 6 on the roof. Of course, these giant turrets, with their outsized guns, tipped the scales at 1,160-tons or about the weight of a standard destroyer of the era, but hey, it’s not like they were going to sink the island or anything.

For comparison, the huge 16-inch/50 cal Mk.7 mounts on the Iowa-class battleships– commissioned decades after the Army’s concrete fort was built, weighed 1,701-tons but had three larger guns rather than the two the boys in green staffed.

The M1909 mount was tested at Sandy Hook Proving Ground, New Jersey before shipment to the PI. Only two of these mounts were ever constructed and, to the credit of the Army, are both still in existence despite an epic trial by combat. Click to big up

As befitting a battleship, the fort had a secondary armament of four casemated 6-inch coastal defense guns (dubbed Batteries Roberts and McCrea) as well as an anti-aircraft/small boat defense scheme (Batteries Hoyle and Exeter) of smaller 3-inch guns.

To direct all this a 60-foot high lattice mount (just like those on the latest U.S. battleships) was fitted to the ‘stern’ of the fort that contained fire control spotters (that fed to plotting rooms protected deep inside the facility), as well as 60-inch searchlights, radio and signal facilities to keep in contact with the rest of the harbor defenses.

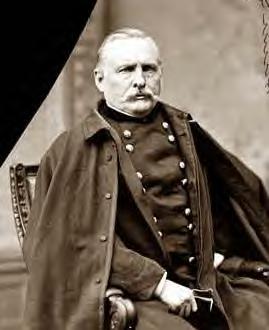

Finally commissioned in 1913– just in time for World War One, the concrete battleship was named Fort Drum after former Adjutant General of the Army Richard Coulter Drum, who had died in 1909– the year construction began.

The fort was a happy post until December 8, 1941, when, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese struck at the Philippines. Largely relegated to providing some far-off gunfire support and exchanging pot shots with Japanese planes until Manila fell, this soon changed.

The fort was a happy post until December 8, 1941, when, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese struck at the Philippines. Largely relegated to providing some far-off gunfire support and exchanging pot shots with Japanese planes until Manila fell, this soon changed.

In December two water-cooled .50 caliber machine guns manned by a 13-man platoon of 3/4 Marines (withdrawn only days before from China), was sent to the concrete battleship to beef up her dated AAA defenses.

They joined the 200~ soldiers, officers, Philippine Scouts, and civilian ordnance-men of the 59th and 60th U.S. Army Coastal Artillery Regiments, commanded by Lt. Col. Lewis S. Kirkpatrick. Later, when Bataan fell, about 20 tank-less soldiers from an armored unit– Company D, 192nd Tank Battalion (formerly Harrodsburg’s 38th Tank Company of the Kentucky National Guard)- managed to escape to Drum and lent their shoulders to the wheel for the last month of the campaign.

As the Japanese had done at Port Arthur in 1904 where they brought in 10-ton Krupp L/10 280mm howitzers from the Home Islands to churn the Russian fortifications to gruel, the Imperial Army shipped new 40-ton Type 45 240 mm howitzers just to batter Fort Drum in March.

Although they peppered the fort’s concrete and knocked out some small guns, Drum kept firing and after April, along with Corregidor and the other harbor forts, became the last piece of real estate owned by the U.S. When the Empire tried to take Corregidor in the end, Drum’s 14-inchers made Swiss cheese of a number of their thin-skinned landing barges, sending many of the Emperor’s best troops to the bottom of the Bay.

On May 6, 1942, some 73 years ago today, when General Wainwright surrendered Corregidor, he included the harbor forts in his order. Although still capable of fighting, the defenders of the fort obeyed orders, smashed their generators, burned their codebooks, spiked their weapons, turned the fire-hoses loose in the interior– paying special attention to the powder rooms, and raised a white flag at noon.

Although the 240~ soldiers and Marines of the garrison did not suffer any deaths in direct combat, their time in Japanese prison camps was by no means easy. A number of their unit, including Kirkpatrick, did not live to see the end of the war. Only one officer, battery commander Capt. Ben E. King, survived. Casualties among the enlisted were likewise horrific.

In the end, they were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and that of the Philippine Presidential Unit Citation, which the 59th carries to this day (as the 59th Air Defense Artillery Regiment)

While the Japanese occupied the concrete battleship and used it as a coastal defense position for the rest of the war, they never did get the M1909s operable again.

Following bombardment by the USS Phoenix (CL-46), on April 13, 1945, the U.S. Army landed on the roof of the once-great fort. They found the Japanese defenders, shut inside its concrete warren under their feet, unwilling to surrender. Therefore, with McArthur’s blessing, a detachment of B Company/13th Engineers, poured 3,000 gallons of diesel/oil slurry down the ventilation shafts and set it off with timed charges as they withdrew.

US engineers and soldiers guarding them, pumping diesel fuel and oil into the innards of Ft. Drum Philippines. Note the 14-inch turret in the background

The fort burned for two weeks and no living Japanese prisoners were taken, only 68 “body remnants” were recovered. These men were sailors and survivors from the ill-fated super battleship Musashi, sent to the bottom just six months prior. So in the end, her final crew were battleship men.

According to an Augus1945 Yank magazine article:

First there was a cloud of smoke rising and seconds later the main explosion came. Blast after blast ripped the concrete battleship. Debris was showered into the water throwing up hundred of small geysers. A large flat object, later identified as the 6-inch concrete slab protecting the powder magazine was blown several hundred feet into the air to fall back on top of the fort, miraculously still unbroken. Now the GIs and sailors could cheer. And they did. As the LSM moved toward Corregidor there were continued explosions. More smoke and debris.

Two days later, on Sunday, a party went back to try to get into the fort through the lower levels. Wisps of smoke were still curling through the ventilators and it was obvious that oil was still burning inside. The visit was called off for that day. On Monday the troops returned again. this time they were able to make their way down as far as the second level, but again smoke forced them to withdraw. Eight Japs-dead of suffocation- were found on the first two levels.

Another two days later another landing party returned and explored the whole island. The bodies of 60 Japs-burned to death-were found in the boiler room on the third level. The inside of the fort was in shambles. The walls were blackened with smoke and what installations there were had been blown to pieces or burned.

In actual time of pumping oil and setting fuses, it had taken just over 15 minutes to settle the fate of the “impregnable” concrete fortress. It had been a successful operation in every way but one: The souvenir hunting wasn’t very good.

Starboard beam view of the battleship USS NEW JERSEY (BB-62) passing between CORREGIDOR (background) and FORT DRUM as she enters Manila Bay. Date: 3 Jul 1983 Camera Operator: PH2 PAUL SOUTAR ID: DN-SN-83-09891 Click to big up

Now, abandoned, the unsinkable battleship with its charred interior spaces lies moldering away in Manila Bay.

Over the years, it has become a tourist attraction and target for scrap hunters who have carried off every piece of metal smaller than they are.

For more information on Fort Drum, please visit Concrete Battleship.org

As for Gen. Drum himself, he is buried at Arlington Section 3, Site 1776.

Specs:

Displacement: It is an island

Length: 350 feet

Beam: 144 feet

Draught: nil, but the fort stood 40-feet high and the lattice tower over 100

Propulsion: None, although the fort had numerous generators

Speed: In time with the rotation of the earth

Complement: 200 men of Company E, 59th Coastal Artillery Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Lewis S. Kirkpatrick (1941-42)

Armament: (as completed)

4xM1909 14-inch guns

4xM1908 6-inch guns

Armor: Up to 36 feet of concrete, with up to 16-inches of plate on turrets

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International.

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find http://www.warship.org/

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

Nearing their 50th Anniversary, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

Scumbag of the Century

US Army financial counselor admits to defrauding Gold Star families: DOJ

A former financial counselor for the United States Army pleaded guilty to defrauding the families of fallen servicemembers out of life insurance payments, the U.S. attorney’s office announced Tuesday.

Gold Star family members are the immediate beneficiaries of servicemembers who have died in active-duty military service and are entitled to a $100,000 payment and the servicemember’s life insurance of up to $400,000, according to the organization.

Caz Craffy, from Colts Neck, New Jersey, pleaded guilty to obtaining more than $9.9 million from several Gold Star families to invest in accounts managed by Craffy in his private capacity without the families’ authorization, according to prosecutors.

Craffy was a civilian employee of the U.S. Army, working as a financial counselor with the Casualty Assistance Office, but he was also a major in the U.S. Army Reserves, where he has been enlisted since 2003, prosecutors said.

From May 2018 to November 2022, the Gold Star family accounts suffered more than $3.7 million in losses and Craffy made more than $1.4 million in commissions, according to prosecutors.

“Those who target and steal from the families of fallen American servicemembers will be held accountable for their crimes,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said in the press release.

“Nothing can undo the enormous loss that Gold Star families have suffered, but the Justice Department is committed to doing everything in our power to protect them from further harm,” Garland said.

On Tuesday, Craffy pleaded guilty to 10 counts, including six counts of wire fraud and one count each of securities fraud, making false statements in a loan application, committing acts affecting a personal financial interest and making false statements to a federal agency, according to the New Jersey U.S. Attorney’s Office’s press release.

“Caz Craffy admitted today that he brazenly took advantage of his role as an Army financial counselor to prey upon families of our fallen service members, at their most vulnerable moment, using lies and deception,” U.S. Attorney Philip R. Sellinger said in the press release.

“These Gold Star families have laid the dearest sacrifice on the altar of freedom. And they deserve our utmost respect and compassion, as well as some small measure of financial security from a grateful nation,” Sellinger said.

Craffy entered his plea before U.S. District Judge Georgette Castner in Trenton, New Jersey and is scheduled for sentencing on Aug. 21.

Craffy’s plea agreement calls for a prison sentence of 8 to 10 years, according to prosecutors, and the restitution amount will be announced during his sentencing.

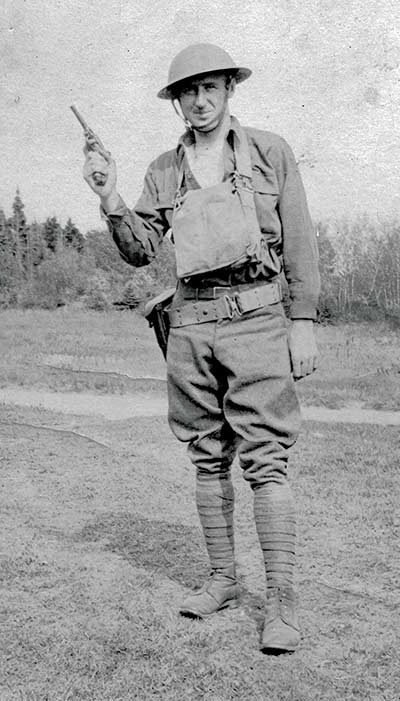

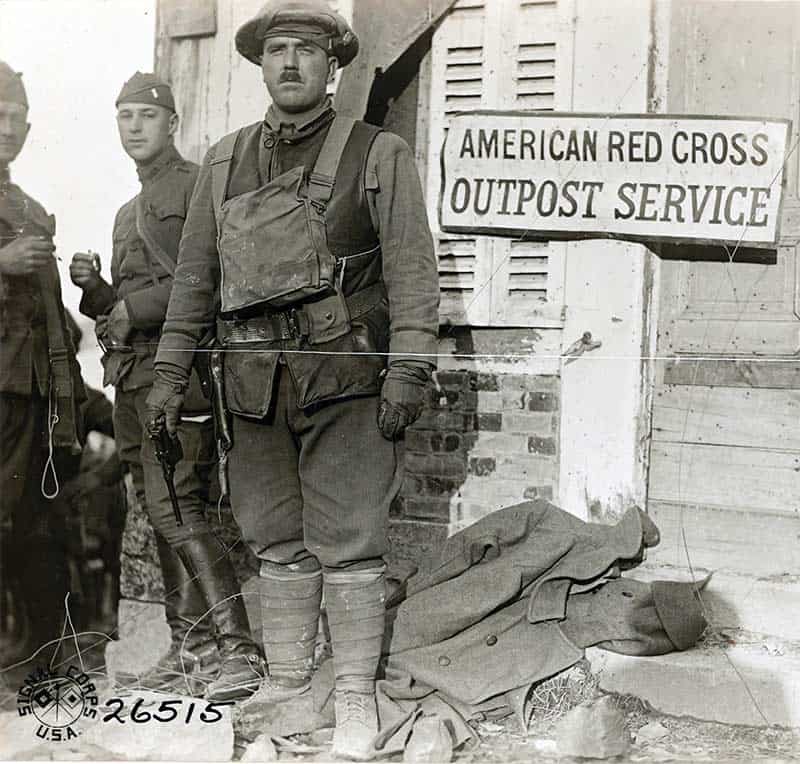

When American troops began to deploy to France in late 1917, they would soon realize the horrors of modern warfare. But they would also find one of the few pleasures for the combat soldier, and in WWI, that meant the beginning of a joyful harvest of German war trophy pistols.

WW I Trophy Hunting

By 1918, the German 9mm Pistole Parabellum, commonly known as the Luger pistol, became one of the most sought-after souvenirs of the Great War. The Luger and the Mauser C96 “Broom Handle” (chambered in 7.63x25mm) were not only prized trophies — the Doughboys found them quite useful and turned them against their former owners.

Even while there were plenty of U.S. .45 ACP pistols available (the M1911 auto pistol and the M1917 revolver), any red-blooded American boy will tell you two guns are better than one — particularly when your life depends on them. Even after the war was over, the American army of occupation in Germany continued its interest in war trophies, particularly the pistol variety.

The expression “The English fight for Honor, the French for Glory, but the Americans fight for Souvenirs!” is said to have originated in 1918. It is confirmed in multiple post-war assessments by German troops and civilians concerning American troops.

U.S. Intelligence officers conducted a series of interviews immediately after World War I. One letter from a German in Treves said: “The American discipline is excellent, but their thirst for souvenirs appears to be growing.” A shopkeeper from Bad Neuenahr quipped: “I alone have sold more Iron Crosses to American soldiers than the Kaiser ever awarded to his subjects.”

German pistols became scarce in the 1918–1919 era and unless you picked one up yourself (the hard way), their prices rose steeply. On the plus side, there were no gun laws in the U.S., so if a Doughboy could capture it, trade for it, or buy it, he could bring that pistol, rifle, or even machine gun home with him. After all, World War I was called “the war to end all wars” and nobody believed this world would be stupid enough to go to war again. But sadly, there would be another bigger and better chance for American troops to pick up German pistols on the battlefield just a quarter-century away.

Act II: ETO War Trophies

When U.S. forces met German troops in combat in World War II, American interest in German pistols, particularly the Luger, was reinvigorated. The U.S. Military Intelligence publication German Infantry Weapons (May 1943) described the Luger in detail for troops in the field:

“The Luger Pistol: Since 1908, the Luger pistol has been an official German military sidearm. In Germany, Georg Luger of the DWM Arms Company developed this weapon, known officially as Pistole 08, from the American Borchart pistol invented in 1893. The Luger is a well-balanced, accurate pistol. It imparts a high muzzle velocity to a small-caliber bullet but develops only a relatively small amount of stopping power.

Unlike the comparatively slow U.S. 45-caliber bullet, the Luger small-caliber bullet does not often lodge itself in the target and thereby impart its shocking power to that which it hits. With its high speed and small caliber, it tends to pierce, inflicting a small, clean wound. When the Luger is kept clean, it functions well. However, the mechanism is rather exposed to dust and dirt.

“Ammunition: Rimless, straight-case ammunition is used. German ammunition boxes will read ‘Pistolenpatronen 08’ (pistol cartridges 08). These should be distinguished from ‘Exerzierpatronen 08’ (drill cartridges 08). The bullets in these cartridges have coated steel jackets and lead cores. The edge of the primer of the ball cartridge is painted black. British- and U.S.-made 9mm Parabellum ammunition will function well in this pistol; the German ammunition will, of course, give the best results.”

Don’t Touch That …

The Luger’s popularity among U.S. troops did not go unnoticed by the Germans. Several wartime cautionary tales emerged as the Luger was sometimes used as “bait” for a booby-trap, ready to catch an over-eager trophy hunter. Other claims were circulated that German troops executed Americans captured carrying German pistols, but this was never substantiated. The February 1945 edition of the U.S. Intelligence Bulletin contained this warning:

“Charges Concealed in Weapons. The Germans sometimes conceal a small charge in the mechanism of a rifle or Luger pistol that they plan to leave behind in a fairly obvious place, to attract the attention of Allied soldiers. The charge, which is sufficiently powerful to injure a man severely, is detonated if the trigger of the weapon is pressed.”

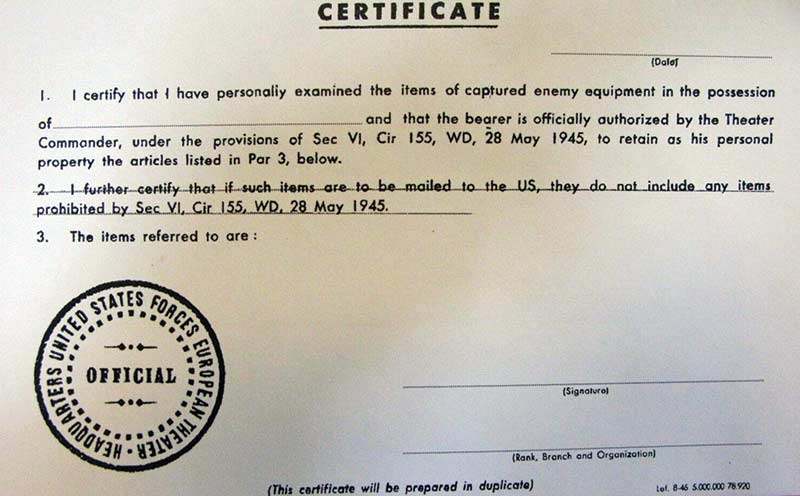

Bring-Backs & Send-Homes

Such was the mania among GI souvenir hunters to pick up German pistols (and any other German firearm) on the battlefield that the U.S. Army and the U.S. Customs Bureau went to great lengths to approve, then control, and then ultimately restrict American troops’ ability to bring or send the captured weapons home.

Beginning in 1944, a U.S. government certificate (often called “capture papers”) was provided to GIs that would allow them to send home or carry home a wide range of war trophies. Signed by their commanding officer, these rather vague certificates gave troops a near carte blanche to pass almost any captured firearm through U.S. customs, at least for a time.

Shortly after the war ended, a U.S. Army regulation effective May 28, 1945, limited War Trophy firearms to one per soldier and strictly enforced the prohibition of the importation of machine guns. It all looked good on paper anyway, but most GIs (and apparently their officers) ignored it. Your dad or grandpa put his captured pistol in his duffel bag and carried it home, or he packaged it up and mailed it to the states.

I’ve never seen any credible estimate on the number of German pistols brought home from the world wars. I’m not good at math, so I won’t guess at the total — other than to say, “a lot.” Even so, it is rare to find a WWII trophy pistol complete with its capture papers — the documentation doesn’t change much, but it is an interesting notch on a collector’s belt.

Technicalities

I did a little digging and found how Uncle Sam defined “war trophies” and the guidelines of how they could be possessed and brought to the United States as personal property.

“War Trophy: In order to improve the morale of the forces in the theatres of operations, the retention of war trophies by military personnel and merchant seamen and other civilians serving with the United States Army overseas is authorized under the conditions set forth in the following instructions. Retention by individuals of captured equipment as war trophies in accordance with the instructions contained herein is considered to be for the service of the United States and not in violation of the 79th Article of War.

“All effects and objects of personal use — except arms, horses, military equipment, and military papers — shall remain in the possession of prisoners of war, as well as metal helmets and gas masks.

“When military personnel returning to the United States bring in trophies not prohibited, each person must have a certificate in duplicate, signed by his superior officer, stating that the bearer is officially authorized by the theatre commander, under the provisions of this circular, to retain as his personal property the items listed on the certificate. The signed duplicate certificate will be retained by the Customs Bureau; the original will be retained by the bearer.

“Military personnel in theaters of operations may be permitted to mail like articles to the United States, except that mailing of firearms capable of being concealed on the person is prohibited. Parts of firearms mailed in circumvention of this prohibition are subject to confiscation by postal authorities. Parcels mailed overseas which contain captured materiel must also contain a certificate in duplicate, signed by the sender’s superior officer, that the sender is officially authorized by the theater commander to mail the articles listed on the certificate. The Customs Bureau will take up the signed duplicate certificate and leave the original inside the parcel.

“By order of the Secretary of War: G.C. Marshall Chief of Staff August 21, 1944.”

Since its inception in the early 1960s, the Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopter has been a symbol of strength, adaptability and endurance in the world of aviation. With its unmistakable tandem rotor design and unparalleled lift capacity, the Chinook consistently demonstrated its ability to perform in a wide range of demanding situations, from military operations to disaster relief and beyond. In this article, Will Dabbs, MD delves into the fascinating history of the CH-47, examines its unique design features, and explores how this remarkable aircraft evolved over the decades to remain a critical asset in both military and civilian applications around the globe.

In my day, at least, when it was time to find out what sort of tactical aircraft you would fly, the U.S. Army didn’t make a terribly big deal about it. Though the rest of our military careers turned on the announcement, we all just gathered in a classroom toward the end of flight school at Fort Rucker, and our company commander read the results off of a computer printout. We were then left to be either elated or crushed as the situation dictated. I was personally crushed.

Not in so many words, but I told the Army I wanted to fly anything in the inventory except CH-47D Chinooks. I collected machine guns and had grown up reading everything I could find about World War II fighter planes. I chose the U.S. Army over the Air Force because I thought attack helicopters were more akin to P-38 Lightnings than might be F-15 fighters. I wanted to fly an airplane, not manage a bunch of systems. I had hoped that helicopter gunships might scratch that itch. And then I got Chinooks.

It’s weird, the U.S. Army. I actually did quite well in flight school, and my instructors all endorsed me for guns. The Chinook transition was quite the desirable slot, it was simply that I didn’t want it. There were other guys who got Snakes but wanted Chinooks. I always suspected Uncle Sam just hated us for some unfathomable reason.

Anyway, as a soldier, you are trained not to get what you want, so we just sucked it up and moved on. And then I actually strapped on a CH-47D, and I realized what all the fuss was about. The Chinook was a simply magnificent machine.

In helicopters, speed and maneuverability are a function of power, not aerodynamics. The Chinook has scads of that. My versions packed an aggregate 9,000 shaft horsepower into two Lycoming turboshaft engines. That made the big Chinook wicked fast.

VNE (Velocity never to exceed) for a CH-47D was 170 knots, or about 195 miles per hour. The Blackhawk and Apache were faster, but only in a dive. The Chinook would walk away from them both in level flight. I actually did that myself several times just to prove a point. When deftly wielded, the CH-47D would turn on a dime as well.

Most conventional helicopters are slaves to tailwinds. The tail rotor on a traditional helicopter is just there to counteract main rotor torque and keep the machine pointed in the right direction. Whatever power is required to keep that thing spinning is essentially wasted. By contrast, the massive twin counter-rotating rotors on the Chinook funnel all that power into lift. It also doesn’t much care what direction it is pointed. I once held a Chinook at a stationary hover in a mountain pass in Alaska and read 73 knots on the airspeed indicator.

Semi-rigid rotor systems like those of the Cobra or Huey cannot be operated at less than one-half of one positive G. Unloading the rotors, like hugging terrain at speed while flying NOE (nap of the earth) across a hilltop, can cause them to come apart. By contrast, the fully-articulated system on the Chinook feasted on negative G’s. According to the simulator, a CH-47D will execute a splendid aileron roll, though I have never tried that myself in the real world.

Details

The D-model CH-47 tops out at 50,000 pounds and is 98 feet long from rotor tip to rotor tip. It features seatbelts for 33 combat troops, but can carry lots more in a pinch. The fuselage is 52 feet long, and each rotor blade spans 30 feet. While weight and balance are always important in helicopters, I found that the Chinook would carry most anything you could stuff into it.

The service ceiling for the CH-47D is listed as 20,000 feet, but I have personally taken one to just shy of 22k. The aircraft has mounts for three defensive machine guns. Ours were sucktastic D-model M60 machine guns. Nowadays, they use M240 guns. The Night Stalkers of the 160th SOAR (Special Operations Aviation Regiment) operate Dillon M134D miniguns. Those are undeniably sexy cool, but an electrically-powered machine gun is just ballast if the electrical system fails or is shot away.

Unlike lesser U.S. Army helicopters, the Chinook is a fantastic instrument platform. The AFCS (Advanced Flight Control System) will fly the aircraft hands-off in cruise mode. Heading changes can be easily effected simply by turning a knob on the instrument panel that orients a heading bug on the HSI (Horizontal Situation Indicator). I’m sure all that is digital today. All of the flight instruments are perfectly replicated on both sides of the cockpit, so the machine is equally friendly from either seat.

CH-47F Chinook Technical Specifications

Here are the published Chinook specifications:

| Crew | 3 (2 pilots, 1 flight engineer) |

| Load Carrying Capacity | 33 troops or 24 litters |

| Length, Overall | 98′ |

| Length, Fuselage | 52′ |

| Weight, Empty | 24,578 lbs |

| Weight, Maximum Takeoff | 50,000 lbs |

| Powerplant | 2x Lycoming T55-GA-714A turboshaft engines with 4,733 SHP each |

| Velocity, never to exceed | 170 knots |

| Service Ceiling | 20,000′ |

| Armament | 3x M240 machine guns |

Pilot Stuff

The tandem rotor design of the CH-47D offers certain benefits not afforded by lesser aircraft. With a little practice, a skilled pilot could cause the machine to pivot precisely around the forward rotor head, the aft head, or the cargo hook in the middle. An awe-inspiring spiraling vertical liftoff executed at maximum power settings was called a Black Cat takeoff. No other machine could really do that.

Pinnacle landings were uniquely cool. With the flight engineer providing guidance the aft landing gear could be precisely located on a mountaintop or something similar. Then by setting the cyclic to the rear, the pilot could plant the aft gear and then use the thrust (what would be the collective in a lesser aircraft) to adjust pitch and maintain station. The same technique could be used to taxi the big helicopter on its back two wheels. The Chinook also made a great paradrop platform. You could feel a little bump through your seat every time one of the heavily-laden paratroopers left the aft ramp.

Practicalities of the Chinook

U.S. Army doctrine, at least in my day before there were so many blasted drones, was to push the tactical aircraft as close to the front as possible. That meant we lived out of our machines. We actually affectionately referred to the CH-47D as the Boeing Hilton. With so much space, there was plenty of room for the crew to lower the sling seats and use them as cots. I have spent weeks on end living out of my aircraft. After an extended period in the field, the inside of the aircraft begins to look like a homeless encampment, but it is still better than the alternative.

Operations in the Arctic bring their own unique challenges. As the machine is basically a big aluminum tube, it doesn’t take long for the aircraft to become cold-soaked at fifty below zero. Our arctic sleeping bags were up to the task, but it was always a gut check to see who was going to be the first out of their fart sack to go crank the auxiliary power unit and get that 200,000-BTU heater cooking. That puppy ran off of jet fuel and would render the Boeing Hilton mosty toasty in no time, no matter how ghastly it was outside.

I later got to fly both AH-1S Cobras and OH-58A/C helicopters. I learned to fly on Vietnam-era UH-1H Hueys in flight school. The Huey had the nostalgia, and the Snake the sex appeal. Driving Aeroscouts single-pilot with the doors off was like flying a motorcycle. However, nothing can compare to the sensation of power you get when you tug the up stick in a CH-47D and feel those 9,000 horses kick you in the butt. That was a wild ride, indeed.