Category: Soldiering

In the late 1880s, the lives of settlers on the Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee had changed little since before the Revolution. Lofty mountains, bridgeless streams, and unpaved roads had isolated the mountain folk from the affairs of the outside world for over a century. Their education and smarts came not from books and “larning,” but from their intimate knowledge of the rugged outdoors. Fiercely independent and self-reliant, they made do with whatever nature and the good Lord provided.

Alvin Cullum York was brought up in these backwoods, where hard work on the homestead made for robust constitutions and where stealth and expert marksmanship in the wilderness were vital for fetching wild game for food sport.

Born on December 13, 1887, Alvin and his ten siblings were raised in a two-room log cabin in Pall Mall, Tennessee, within spitting distance of the Kentucky state line.1 There, in the sun-drenched valley of Three Forks of the Wolf River, the Yorks tended to their seventy-five-acre farm, “part level and part hilly,” where they grew corn and raised chickens, hogs and a few cows for their subsistence.2 To make ends meet, his father, William, worked as a blacksmith, setting up shop in a mountain cave near their home. His mother, Mary, would do chores at neighbor’s homes, sometimes accepting old clothes as payment, which she would mend and alter for the children.3

York family log cabin. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 33.

York family log cabin. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 33. Valley of the Three Forks O’ the Wolf. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 89.

Valley of the Three Forks O’ the Wolf. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 89.

Schools in the remote mountain regions were scarce and poorly funded, not that it mattered much for the older children had to help harvest the crops as a matter of priority. In the winter, keeping school open was impractical as many of the children had to travel long distances and lacked warm clothes and proper shoes. The one-room schoolhouse in Pall Mall was open for only 2 ½ summer months a year; Alvin attended three weeks a year for five years, receiving the equivalent of a second-grade education.4

Alvin picked up hunting skills from his father and his grit from stories of “fightin’ men” like Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Andrew Jackson. For Alvin, hunting was not just a skill but an art. A man had to become intimately acquainted with his rifle’s parts, meticulous with its care, and familiar with its “temperament,” whether its fire would lean left or right or if the sun or the wind, dry or damp days would affect its performance. As an experienced hunter, Alvin could read and interpret signs left by wild animals, blend into the woodlands, and remain motionless while stalking his prey. At local shooting matches, with his old muzzle-loading “hog rifle,” he “could bust a turkey’s head at most any distance” and “knock off a lizard’s or a squirrel’s head from that far off that you could scarcely see it.”5

When his father died in 1911, York went “hog wild,” cussing and gambling and drinking moonshine, the latter often in challenges where the winner was the last man standing. He found himself in trouble with the law on more than one occasion.6 Although he never shunned his responsibilities at home, his sinful ways caused his ma many a sleepless night in prayer. In her quiet manner, she begged her son to change. As a Christian woman, she knew that his sins were wasting his life and destroying his chances for salvation. As a mother, she feared for his personal safety each time he went past the front gate.

Alvin, now twenty-seven years old, began to assess his life and often went into the mountains to pray and ask God to help him fight his demons. He started attending the Wolf River Church where a saddlebag preacher’s sermons further enlightened Alvin to a life of righteousness. His growing fondness for Gracie, a local beauty thirteen years his junior and devout Christian, boosted his motivation to change. 7 On January 1, 1915, York swore off his vices and joined the Church of Christ in Christian Union. A fundamentalist sect, it opposed all forms of violence and advocated a strong pacifist philosophy which York adopted. 8 Now a devout Christian, his new-found beliefs were about to be tested.

Hints of War

On April 6, 1917, the United States of America formally declared war on the German Empire when German U-boats attacked U.S. ships in the Atlantic. Word got around Pall Mall about the escalating war, but little was understood about its causes, our involvement, or its objectives. “I knowed big nations were fighting, but I didn’t know for sure how many and which ones…I had no time nohow to bother much about a lot of foreigners quarreling and killing each other over there in Europe.”9

On May 18, the U.S. government enacted a law requiring that all able-bodied men between the ages of twenty-one to thirty-one register for the draft. York reluctantly registered on June 5 but attempted to gain status as a conscientious objector. Three separate requests for exemption from selective service, including one from his pastor and mentor, Rosier Pile, were summarily denied by the local and district boards. Their reasoning was that the church had “no especial [sic] creed except the Bible, which its members interpret for themselves…”10

Fentress County recruits, November 15, 1917. Alvin York is fourth from left.

Fentress County recruits, November 15, 1917. Alvin York is fourth from left.

From Hogue, History of Fentress County, xiii.

Throughout his time at Camp Gordon, York was deeply torn between the pacifist teachings of his church and a moral obligation to serve his country. He received counseling from his superiors, Captain Edward Danforth and Major Gonzalo Edward Buxton.11 They managed to convince York to reconsider his role in the Army by referencing chapters from the Bible regarding war and sacrifice. After spending a few days home while on leave, the young private returned to camp, convinced that serving his country was God’s will.12

York was assigned to Company G, 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry, 82nd “All American” Division on February 1, 1918, and trained at Camp Gordon in Chamblee, Georgia, just northeast of Atlanta. Not surprisingly, he qualified as a sharpshooter when he was able to hit eight out of ten moving targets at 600 yards.13

Over There

The 328th Infantry shipped out from New York and arrived in Liverpool, England, on May 16, 1918, then moved on to Southampton, England, and Le Havre, France, where they landed on May 21, 1918. At Le Havre, their U.S. model of 1917 .30 cal. rifles were exchanged for British Mark III Lee-Enfield rifles, but they were able to keep their 1911 Colt .45 pistols.14 One month later, an assumption that the 82nd Division would be attached to British troops in the region of Picardy was overturned, and the 82nd was instead ordered to Toul. With that, the Lee-Enfield rifles, along with other armaments, were returned to the British and the U.S. model of 1917 Enfield bolt-action rifles were reissued.15

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1917 Enfield most likely used by Alvin York. Manufacturer: Eddystone.

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1917 Enfield most likely used by Alvin York. Manufacturer: Eddystone.

Courtesy Missouri Historical Society.

British Mark III Lee-Enfield Rifle. Courtesy National Army Museum, London.

British Mark III Lee-Enfield Rifle. Courtesy National Army Museum, London.

By then, the war along the Western Front had become a bloody stalemate with heavy fighting along a series of trenches stretching from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps. Reinforced by the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the Allies went on the offensive trying to break through German defenses in northern France.

From Le Havre, the 82nd Division traveled east by train and on foot, past idyllic small towns and serene countrysides, a cruel paradox of what was to come. On June 26 near Rambucourt, York heard the first sounds of gunfire “jes like the thunder in the hills at home.” At Mont Sec, bullets whizzed past “like a lot of mad hornets or bumblebees when you rob their nests.” Here he was placed in charge of an automatic weapons squad and shot French Chauchat machine guns, which he described as being heavy, clumsy, inaccurate, and noisy. “They weren’t near as good as the sawed-off shotguns,” he’d say.16 In September, York was promoted to corporal just before his regiment seized the town of Norroy.17

In the Valley of Death

1st Division Meuse-Argonne Offensive map compiled by American Battle

1st Division Meuse-Argonne Offensive map compiled by American Battle

Monuments Commission, 1937. Click map to enlarge.

On October 7, 1918, the 1st Battalion, 328th Infantry was ordered to take Hill 223, a strategic position just three kilometers southeast of their main objective: the Decauville rail line. This mission came during a critical phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive as American and French troops attempted to achieve the breakthrough that could end the war.18

On the night of October 7, York and the men of the 2nd Battalion watched and waited from the main road between Varennes and Fléville for their turn to continue the assault beyond Hill 223. At 0300 hours, bogged down by heavy rains and mud, fatigued from a sleepless night, hampered by a trek devoid of light except for the glow of gunfire hailing down around them, the troops slogged towards the hill amid utter chaos.

“Lots of men were killed by the artillery fire. And lots were wounded. The woods were all mussed up and looked as if a terrible cyclone done swept through them. But God would never be cruel enough to create a cyclone as terrible as that Argonne battle. Only man would ever think of doing an awful thing like that.”

At 0610 hours, York’s battalion along with three other companies of the 328th Infantry, pushed off Hill 223 with fixed bayonets. The advance was to be preceded by a rolling barrage of artillery fire that never came.19

As the troops raced downhill and charged across the 500-yard valley, now exposed with the light of dawn, an explosion of gunfire erupted from the heights above. “We had to lie down flat on our faces and dig in. And there we were out there in the valley all mussed up and unable to get any further with no barrage to help us, and that-there machine-gun fire and all sorts of big shells and gas cutting us to pieces.”

Valley just west of hill 223 across which York and the 2nd Battalion attacked on the morning of October 8, 1918.

Valley just west of hill 223 across which York and the 2nd Battalion attacked on the morning of October 8, 1918.

From Candler, History of Three Hundred Twenty-Eighth Infantry, 60.

The first wave of men had been decimated by the Germans, and now York’s battalion lay pinned down, able to move but a few feet at a time. Something had to be done, but a frontal attack was out of the question.

When platoon sergeant Harry Parsons realized that the thrust of the machine gun fire came from a ridge to the left, he ordered Sergeant Bernard Early to lead Corporals York, Savage, and Cutting and three squads totaling thirteen men, to silence the machine gun nest on the ridge. Seventeen soldiers stealthily climbed up the left flank, concealed by the thick undergrowth, slipped deep into German lines and encircled the enemy gunners from the rear. While chasing the first two enemy soldiers they encountered, the squads stumbled upon a German headquarters with fifteen to twenty unsuspecting soldiers and officers from the 120th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment in conference.20 Caught completely off guard, the Germans surrendered. While the prisoners were being searched, enemy gunners situated on the ridge above the camp turned their machine guns around and swept the open space, instantly killing six American soldiers, including Corporal Savage, and wounding three. Among the wounded were Sergeant Early and Corporal Cutting. Corporal York was now in charge with just seven men under his command.

The onslaught of machine gun fire from above was relentless and destructive. The German prisoners had hit the ground and the Americans had shielded themselves between them, some of the privates managing to get off a shot or two.21 York was caught out in the open about twenty-five yards below the machine gun line near the ridge, his men and the German POWs huddled behind him. Each time a German soldier raised his head, York would “tech him off,” just like he did at the turkey shoots back home.

Colt .45 government model of 1911. Garry James, American Rifleman.

At some point, York stood up and began to shoot his rifle offhand. His weapon was getting hot and he was running out of ammunition. So when a German officer led a counter-attack with six of his men charging towards York with fixed bayonets, York drew his Colt .45 automatic and, from back to front, shot each one, a practice he picked up at wild turkey shoots in Pall Mall. The idea was to hit the rear soldiers first so that the remainder would not see their comrade fall and fire at him. “It was either them or me and I’m a-telling you I didn’t and don’t want to die nohow if I can live,” he said.

Falling back on his hunting experience in Tennessee, York continued to methodically pick off German soldiers one by one, each time hollering for them to give up. Alarmed by the number of troops being shot dead and their shattered morale, the German commander, Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, shouted out in English offering to surrender his troops.22 As the Germans began to emerge from the upper trenches, one fellow hid a grenade in his raised hand, which he threw at York but missed, hitting another prisoner. York reflexively shot him, and there was no further trouble.

York ordered the eighty to ninety prisoners to form two lines and had them carry Sergeant Early on a stretcher. Using them as cover, York placed Vollmer in front of him with his pistol trained on his back and the other two German officers on either side of him. Seeing that York was considering which way to go, Vollmer suggested to turn down a gully, but York quickly figured it was a trap and decided to go in the opposite direction. Since York and his men had captured the rear German line, they inevitably ran into the first line of enemy trenches. He succinctly told Vollmer to order them to surrender or he would blow the commander’s head off, and they did, joining the lines of POWs headed to the command post.23

York and his men marched the prisoners from one command headquarters to another against his men’s better judgement, until the captives were finally accepted at division headquarters in Varennes, a distance of 10 ½ kilometers. Altogether, York killed 20-25 enemy soldiers, neutralized thirty-five machine guns, and captured 132 German soldiers, though he was quick to reject full credit for the extraordinary success of his mission. “There were others in that fight besides me… I’m a-telling you, they’re entitled to a whole heap of credit. It isn’t for me, of course, to decide how much credit…But jes the same, I’m a-telling you, a heap of those boys were heroes, and America ought to be proud of them.”

His actions enabled the 328th Infantry Regiment to advance across the valley and capture the strategic Decauville Railroad. With their Army on the verge of total collapse and the Central Powers facing defeat on all fronts, Germany agreed to an armistice with the Allies on November 11, 1918, bringing the war to an end.

“I jes want to go home.”

Alvin C. York was promoted to the rank of sergeant on November 1, 1918. He received numerous American and foreign awards, including the highest recognition that could be bestowed upon a U.S. soldier, the Congressional Medal of Honor. French General and Supreme Allied Commander, Ferdinand Foch, commented to York, “What you did was the greatest thing accomplished by any private soldier of all the armies of Europe.”

When York returned to the United States, he found that he had become a national celebrity. It was all so overwhelming for the humble hero, but all he really wanted was to go home. He received offers from Hollywood and Broadway to adapt his life story into a movie and numerous endorsement deals and public appearances worth tens of thousands of dollars. York chose not to capitalize on his newfound fame. He once famously stated “This uniform ain’t for sale.” Instead he dedicated himself to his family and a number of charitable causes. He became a proponent for veterans’ rights, education, and economic development for his impoverished community. Seeking to raise money to help build a bible school, York finally gave his blessing for Hollywood to produce a film based on his life story. In 1941, Sergeant York was released in theaters, starring Gary Cooper in the title role that would earn him an Academy Award. It was the highest grossing film of the year, inspiring young Americans across the country to enlist in the U.S. armed forces during World War II.24

On September 2, 1964, Alvin C. York passed away at a veterans’ hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, at the age of 76. He is currently buried at the Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee, next to his wife, Gracie, who passed away twenty years later.

Alvin C. York has maintained the status of an American folk hero whose story still resonates with Americans to this day. His heroism in battle, his legendary sharpshooting skills, his underprivileged upbringing, his faith in a higher power, his sense of patriotic duty, and his humble nature all contributed to the legend that is Sergeant York. His story is regarded as one of the most inspirational American success stories, and he has been memorialized as one of the greatest heroes in the long history of the United States Army.

Enfield vs Springfield Rifle Debate

Much discussion has centered around whether York used a 1903 Springfield or a 1917 Enfield rifle during the war. WW I munitions data presented by Assistant Secretary of War, Benedict Crowell, concluded that 12-15% of rifles issued were Springfield guns but the vast majority were 1917 Enfields.25

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1903 Springfield. Twelve to fifteen percent of rifles issued to WW I soldiers were Springfields. Wikimedia

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1903 Springfield. Twelve to fifteen percent of rifles issued to WW I soldiers were Springfields. Wikimedia

In his diary, York did not specify the type of rifle he used. Per Colonel Buxton, the 82nd Division was issued 1917 Enfields.26 In 2005, writer Garry James documented a conversation he had with York’s son, Andrew, who stated that his father had somehow switched his 1917 Enfield for a 1903 Springfield because the Enfield “had a peep sight with which York had difficulty leading a target.” Another individual commented on a forum that Andrew York told him that when his father’s unit reached the front, they were given a choice of one of the surplus ’03 Springfields, and that York switched, in part, because “the notched rear sight and post or blade front sight” were virtually the same as on his old muzzleloader. On both occasions, Andrew incorrectly stated that his father trained stateside on the ’03 Springfield and that these were replaced with Eddystones at Le Havre (Woodsrunner 38 second entry). A third forum commentator who also met Andrew York questioned Andrew’s knowledge base on the subject. (See Scott in Indiana). Regardless of which rifle he used, Alvin York’s extraordinary feat is well documented and undeniable.

Video

Words spoken by York voiceover actor are directly from his diary. Great short film with some actual war footage.

Sources

[1] Sam K. Cowan, Sergeant York and his People (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1922), 147. Alvin York, His Own Life Story and War Diary, Tom Skeyhill, ed. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1930), 18, 122. Albert Ross Hogue, History of Fentress County, Tennessee: The Old Home of Mark Twain’s Ancestors (Nashville: Williams Printing Co., 1916), ix-xiv. Eventually, William York built an addition to the cabin separated from the main living area by a breezeway described as a “dogtrot;” see “York’s Early Life,” Tennessee Virtual Archive, and John Perry, Sergeant York (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 9.

[2] Cowan, Sergeant York, 105-106.

[3] David D. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985), 4. York, His Own Life Story, 125.

[4] Cowan, Sergeant York, 169-170. York, His Own Life Story, 123-124. The one-room schoolhouse held pupils ages six to twenty.

[5] York, His Own Life Story, 133-134.

[6] Ibid., 132.

[7] Ibid., 141-145. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 8-10. It has been reported that the untimely death of York’s friend, Everett Delk, was one of his prime reasons for changing his life in 1917. However, author Tom Skeyhill, who interviewed York in 1927 for his book, His Own Life Story and War Diary, stated, “…and that was when he [York] learned that I had interviewed Everett Delk, his pal of “hog-wild days” to which Alvin responded, “Everett must’ve told you God plenty.” (York, 33) After he changed his ways and joined the church, York mentions that Everett or Marion would tempt him to join them for parties but he would refuse (York, 146.) On Find a Grave, there is a record of an Elijah Everett Delk from Fentress County, 1894-1928.

[8] Mark Sidwell, “The Churches of Christ in Christian Union: A Fundamentalism File Research Report,” Bob Jones University Mack Library, (Feb. 16, 2004): 1-3.

[9] York, His Own Life Story, 149-150.

[10] Ibid., 156-163.

[11] York erroneously referred to Major Buxton’s first name as George, an understandable assumption since Buxton always used the initial G. See Ned Buxton, “Sergeant York’s Major,” No Greater Calling, July 13, 2006.

[12] “Conscience Plus Red Hair Are Bad for Germans.” Literary Digest 61, no. 11 (June 14, 1919): 46. George Pattullo, “The Second Elder Gives Battle,” Saturday Evening Post 191, no. 43 (April 26, 1919): 3. York, His Own Life Story, 172-176.

[13] Cowan, Sergeant York, 242.

[14] York, His Own Life Story, 194, 230. Official History of 82nd Division of American Expeditionary Forces 1917-1919, G. Edward Buxton, Jr., ed. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1919), 3, 11. Center of Military History, United States Army in the World War 1917-1919: Training and Use of American Units With the British and French Volume 3 (Washington D.C.: Gov’t Printing Office, 1989 Reprint), pg. 51, para 1a,b,e. Leo P. Hirrel, Supporting the Doughboys: U.S. Army Logistics and Personnel During WW I (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2017), 21. “Weapons of the Western Front: Rifles,” National Army Museum (UK), accessed April 1, 2019. Bruce Canfield, “The U.S. Model of 1917 Rifle, American Rifleman, July 19, 2018. The U.S. was so unprepared for war that drill training at Camp Gordon began with wooden guns (Buxton 3, 226. Hirrel 21).

[15] Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 12.

[16] York, His Own Life Story, 201.

[17] Ibid., 209.

[18] Scott Candler, History Three Hundred Twenty-Eighth Infantry, Eighty-Second Division, American Expeditionary Forces, United States Army, (Atlanta: Foote & Davies Co., 1920), 43-65.

[19] Ibid., 217-220. Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 51-59.

[20] York, His Own Life Story, 224. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 31-33.

[21] York, His Own Life Story: 246, 256, 264.

[22] Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 36.

[23] York, His Own Life Story, 229-231.

[24] Michael E. Birdwell, Celluloid Soldiers: The Warner Bros. Campaign Against Nazism 1934-1941 (NY: NYU Press, 1999), 107-110.

[25] Benedict Crowell, America’s Munitions 1917-1918: Report of Benedict Crowell, the Assistant Secretary of War, Director of Munitions (Washington D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1919) 183.

[26] Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 3.

There are never any war movies about truck drivers. The movies are always about the door kickers, the submariners, or the fighter pilots. However, wars are generally not technically won by such as these. It was the Red Ball Express with its endless lines of 2 and ½-ton trucks that did more to win the Second World War for the Allies than most anything else.

Artificial harbors constructed on the Normandy assault beaches at great expense and effort helped sustain the Allied drive until more permanent solutions could be found.

Artificial harbors constructed on the Normandy assault beaches at great expense and effort helped sustain the Allied drive until more permanent solutions could be found.With the Normandy invasion beaches firmly in Allied hands American and Commonwealth forces fanned out across Western Europe seizing terrain, villages, and populations from the occupying Germans as they went. However, in short order, it became obvious that the logistical demands of these rampaging armies could not be met by the Mulberry ports in Normandy. The answer, among other things, was the Belgian port of Antwerp.

The city of Antwerp itself fell to the British 2d Army roughly one month after D-Day. By mid-September, however, the British 21st Army Group was consumed with Operation Market Garden, the ill-fated airborne brainchild of Field Marshal Montgomery. As a result, while British forces held Antwerp, they still did not have control of the seaside approaches, particularly Walcheren Island. This modest island overlooked the Scheldt Estuary and was heavily garrisoned by the German 15th Army. With the Germans entrenched on Walcheren Island and covering the approaches to Antwerp the Allies were unable to use the port to unload supplies for the advancing combat forces. The result was the Battle of the Scheldt.

The Captain of Chaos

The assault to seize Walcheren Island distilled down to a series of complex interrelated operations. RAF Bomber Command, in a profoundly controversial decision, bombed the dikes at Westkapelle, Flushing, and Veere, flooding the island. This move barely inconvenienced the defending Germans who held the high ground but was utterly catastrophic for the civilians who lived there.

At 0545 hours on November 1, 1944, elements of No 4 Commando churned ashore. They landed in the scant light of dawn just east of the Oranjemolen, a prominent windmill on the sea dike at a spot called Flushing. The main force of this combined French and English unit landed around 0630. At that point things got real.

By 1944 LTC Robert Dawson was a seasoned and respected Commando officer.

By 1944 LTC Robert Dawson was a seasoned and respected Commando officer.The commander of No 4 Commando was one LTC Robert W.P. Dawson. LTC Dawson, like so many other combat commanders, was faced with the unfettered chaos of pitiless close quarters combat. The Commandos had the resources and they had a plan. However, the Germans had other ideas.

Dawson’s small reconnaissance element landed via a pair of LCP (Landing Craft Personnel) boats. The American version of this versatile craft was the legendary Higgins boat. These shallow-draft workhorses featured bow ramps that could drop to disgorge troops on a hostile beach. The experience of riding a Higgins boat into battle against an entrenched enemy would have been unimaginably horrible, but they were tried and proven.

By the time the main body landed at 0630, the Germans were fully activated, raking the landing areas with fire from small arms as well as a fast-firing 20mm antiaircraft cannon. The No 4 Commando LCA (Landing Craft Assault) boats carrying their heavy weapons foundered on stakes placed in the surf and sank some 20 yards from the beach. The Commandos nonetheless salvaged their three-inch mortars and used them to good effect as they rolled up the German defenses.

The Commandos reduced each German strongpoint sequentially. Early in the morning the battle seemed about evenly matched. However, with the arrival of the lead battalion of the British 155thInfantry Brigade, the tide began to turn. As the Commandos seized German prisoners they were sent to the beaches to help unload supplies. Once the Commandos cleared these emplacements they found them to be well-supplied with food and ammunition. However, the German troops were second-rate, many of them suffering from medical maladies after being so long away from proper support.

Throughout it all, LTC Dawson deftly led his men from the front. Dawson peeled off rearguard elements as needed to secure the German defensive positions against subsequent infiltration. By 1600 that day No 4 Commando’s primary objectives had been seized.

The Man

LTC Robert William Palliser Dawson spent the entire war with No 4 Commando. He joined the unit in 1940 as one of its first subalterns. In August of 1942, Captain Dawson commanded C Troop during the ill-fated raid on Dieppe.

By 1943, Dawson was promoted to Major and was serving as XO of No 4 Commando. In April of that year, Lord Lovat relinquished command of the unit to Dawson, and they began training in earnest for D-Day. On June 6, 1944, Dawson found himself at Ouistreham as part of Operation Overlord.

Dawson was wounded twice during this assault but refused medical evacuation. Despite his injuries, he continued to lead his men in combat. The citation for his subsequent decoration states, “It was due to his leadership and direction that the attack was successfully pressed home.”

When LTC Dawson landed at Flushing as part of Operation Infatuate, he carried a unique prototype weapon. After the miraculous evacuation at Dunkirk, the British found themselves with an Army but few firearms. The inexpensive Sten submachine gun helped carry them through the dark days as they desperately rebuilt their military into a viable fighting force. By 1944, however, British industry had crafted an improved replacement.

The Sterling Patchett

Using the Sten as a starting point, the British General Staff issued the specifications for its replacement in early 1944. The new gun should weigh no more than six pounds and fire 9mm Para ammunition. The rate of fire should be less than 500 rpm, and the gun should be adequately accurate to place five consecutive semiautomatic shots within a one-foot-square block at 100 yards.

George William Patchett was the chief designer at the Sterling Armaments Company, and he had his first operational prototype ready for testing in early 1944. Officially known as the Patchett Machine Carbine Mk 1, the Patchett gun fired from the open bolt and fed from the left in the manner of the Sten. Unlike the Sten, however, the Patchett gun had the feed mechanism located over the pistol grip for improved balance.

The Patchett incorporated some novel design features. The bolt featured helical cuts to move debris and fouling clear of the action as it cycled. The underfolding stock, though complicated, collapsed to about nothing yet offered a steady platform for accurate fire when extended. Most importantly, however, the Patchett did away with the Sten’s ghastly double column, single-feed magazine.

The curved double column, double-feed magazine of the Patchett gun featured a novel follower made of roller bearings and was likely the best submachine gun magazine ever devised. These boxes carried 34 rounds and were easy to orient in the dark. As magazine supply could have been an iffy thing in the latter parts of WW2, the Patchett was designed to accept either Sten or Patchett mags seamlessly.

The British were impressed with the Patchett and ordered 120 copies for combat trials. A few of these weapons saw limited service with the Paras at Arnhem during Operation Market Garden. LTC Dawson carried one of these first 120 guns during Operation Infatuate. The weapon he wielded during this critical operation, serial number 78, is currently on display with the Imperial War Museum.

The exigencies of total war hampered the adoption of the Patchett gun, and it was not until 1951 that the decision was made to replace the Sten. The Patchett was rechristened the L2A1 Sterling and issued throughout the British military. The Sterling soldiered on until 1994 when it was replaced by the L85A1 assault rifle. The Sterling saw some of its most widespread exposure as the basis for the BlasTech E-11 Blasters wielded by the Imperial Stormtroopers during the timeless sci-fi epic Star Wars.

The Rest of the Story

Several other Commando units landed around Westkapelle as part of Operation Infatuate, seizing intermediate objectives and reducing enemy strongpoints. One of these, 47 Commando under the command of LTC C.F. Phillips, eventually fought their way around the periphery of the island to link up with Dawson and his Commandos in their consolidated positions.

With the support of HMS Warspite, Roberts, and Erebus as well as rocket-firing landing craft and a squadron of Typhoon fighter-bombers the Commandos were ultimately successful. Along the way, they captured some 40,000 Germans. After extensive minesweeping operations to clear the estuary the first Allied cargo vessels unloaded in November of 1944. This efficient port along with its associated transportation arteries served as a critical source of supply for the bloody fighting that was to come.

LTC Dawson was President of the Commando Association after the war and was described as, “Charming, kind, and understanding” by those with whom he served. Dawson was honored as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). He died in 1988 at the age of 74, a hero from a generation of heroes, and one of the first men to carry the Sterling submachine gun in combat.

Talaiasi Labalaba was born on July 13, 1942, in Vatutu Village in Nawaka, Nadi, on the island of Fiji. Fiji is an island country in Melanesia in the South Pacific roughly 1,100 miles northeast of New Zealand. Fiji is actually an archipelago of more than 330 islands, 220 of which are currently uninhabited. Tourism and sugar-cane are the primary industries. As of 1970, Fiji became a fully independent sovereign state within the British Commonwealth of Nations. Beginning in WW2, Fiji’s relationship with the British Empire meant that native Fijians could serve in the British military.

Labalaba spent his childhood on an island and craved adventure. He initially enlisted with the Royal Ulster Rifles and also served with the Royal Irish Rangers. Eventually, Labalaba volunteered for Selection for the 22d Special Air Service.

The Setting

In the summer of 1972 Oman was in chaos. Sharing borders with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen, the Omani Sultanate was allied with the British in a fight for its life against Marxist rebels. A small contingent of nine SAS operators was assigned to assist with Omani security as part of the British Army Training Team at Mirbat. Their year-long deployment was part of Operation Jaguar. This nine-man team was short and was soon to rotate home.

Opposing this small contingent was the PFLOAG. This mouthful of word salad stands for the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf. Locals just called them the Adoo.

The SAS BATT House stood overlooking the approaches to Jebel Ali, itself a strategically critical piece of dirt leading to the major port of Mirbat. The PFLOAG rebels knew that to take Mirbat they would first have to take Jebel Ali. Before they could get to Jebel Ali they had to neutralize the nine Brits at the SAS BATT House.

The BATT House was itself a fairly impressive fortification. Manning the fort as well as the surrounding encampment were another 25 Omani policemen and some 30 Balochi Askari along with one local firquat irregular. The Balochi Askari were members of the Pakistani diaspora serving in an administrative military capacity. The firqua were members of the Omani loyalist militia.

Arrayed against this Neapolitan band was some 300-400 heavily-armed and dedicated PFLOAG Marxist fighters. At the BATT House, the SAS troops were armed primarily with L1A1 SLR rifles and a single M2 .50-caliber machinegun along with a 60mm mortar. The Adoo packed AK47 rifles, RPG7’s, and mortars along with ample ammunition courtesy of their Soviet and Chinese benefactors.

July 19, 1972, was the day the Brits were to rotate home. At 0600 that morning, CPT Mike Kealy, the 23-year-old commander of the SAS contingent, observed what he thought to be a deployed patrol of loyal Omanis now returning to base. These Omanis had been picketed to warn of approaching Adoo forces. Once he realized how substantial this force was, however, he appreciated that his patrol had surely been killed. He then ordered his men to open fire. The SAS troops did just that but found that the Adoo forces were infiltrating via gullies beyond the effective range and penetration of their SLRs. At that point, the BATT House began receiving accurate and effective mortar and RPG fire. CPT Kealy contacted his higher headquarters in Um al Quarif and requested reinforcements.

The Fight

It soon became obvious that the small SAS force was in grave danger of being overwhelmed. However, located some 800 meters distant at a smaller fortification was a single British 25-pounder artillery piece along with an ample supply of ammunition. SGT Talaiasi Labalaba struck out alone across 800 meters of flat open desert to reach the howitzer. The accumulated Adoo insurgents opened up on him with their AK rifles.

The typical crew for a 25-pounder is six. This multipurpose Quick-Firing gun fired separate ammunition consisting of a projectile loaded first followed by a cartridge case containing between one and three bags of propellant. Running the gun accurately, efficiently, and well is an art that requires extensive cultivated teamwork and training. On this fateful day, SGT Labalaba was managing the big 3,600-pound gun alone.

During the course of several hours, SGT Labalaba poured high explosive rounds into the attacking communist guerrillas, frequently averaging one round per minute. However, the sheer force of numbers was overwhelming him. Eventually, the attacking Adoo troops got an AK round past the splinter shield on the gun and struck SGT Labalaba in the face. Now badly wounded, he radioed back to the BATT House with an update. Despite the horrific nature of his injury SGT Labalaba continued firing the howitzer, sighting directly through the bore at the approaching guerillas. However, he was badly hurt and losing blood. SGT Labalaba was now struggling to operate the heavy gun alone.

CPT Kealy requested a volunteer to assist SGT Labalaba and Trooper Sekonaia Takavesi, a fellow Fijian, answered the call. Under covering fire from the BATT House Takavesi made the long 800-meter run to the artillery emplacement unscathed. Once there he engaged approaching Adoo fighters with his SLR and attempted to address SGT Labalaba’s injury as best he could. Together the two men continued to work the 25-pounder, pouring HE rounds onto the maniacal communist attackers.

The Gun

Developed in 1940, the 25-pounder was an 87.6mm multipurpose artillery piece combining both high-angle and direct-fire capabilities. Ultimately produced in six Marks, the 25-pounder was highly mobile for its day despite its nearly two-ton all-up weight. The gun was used throughout the Commonwealth, and ammunition remains in production at the Pakistani Ordnance Factories today.

The 25-pounder used separate bagged charges that could be cut as necessary to produce an accurate fall of shot at various ranges. A subsequent “Super” charge was also developed that required the addition of a muzzle brake to the gun for safe operation. Most British charges for the gun were cordite-based.

In addition to high explosive, smoke, and chemical shells, the 25-pounder could also fire a curious shaped-charge warhead as well as a 20-pound APBC (Armor Piercing Ballistic Cap) round also designed for antitank use. Antitank rounds were employed in the direct-fire mode using Super charge loads. In addition to these conventional applications, the 25-pounder could also fire foil “window” that mimicked the return of an aircraft on radar as well as shells containing propaganda leaflets. These leaflet shells were employed toward the end of WW2 to convince the Germans to surrender.

The Rest of the Story

Now under dire threat of being overrun, SGT Labalaba retrieved a small Infantry mortar kept at the artillery firing point. This stubby high-angle weapon would be more effective now that the attacking troops were in so close. As he moved to set the mortar up for firing he caught a second round to the neck and bled out.

By now Takavesi had also taken a round through the shoulder and was grazed by another across the back of his head. Despite his injuries, he duly reported the situation back by radio and continued to engage the approaching guerillas with his SLR.

In response, CPT Kealy and another SAS trooper named Thomas Tobin also ran the gauntlet to the artillery firing point. When they arrived they found that Trooper Takavesi had been hit a third time, this time by an AK round through his abdomen. Now having closed to within-hand grenade range, the PFLOAG troops showered the emplacement with grenades, only one of which detonated.

During the fight, Trooper Tobin reached across the body of SGT Labalaba and caught an AK round to the face that blew away much of his jaw, leaving him mortally wounded. Just when the situation seemed darkest, a flight of BAC Strikemaster attack jets from the Omani Air Force arrived on station and opened up on the communist rebels. One of the jets suffered battle damage from ground fire and had to return to base, but rocket and cannon fire from the remaining element ultimately broke the back of the assault.

When Trooper Toobin was hit he reflexively aspirated a chunk of his own splintered tooth. This fragment subsequently set up a lung infection that later killed him in hospital. Sekonaia Takavesi was medically evacuated and recovered. SGT Talaiasi Labalaba received a posthumous Mention in Dispatches. SGT Labalaba is buried at St Martin’s Church at Hereford in England. He was 30 years old when he was killed.

The 25-pounder gun SGT Labalaba used in Oman is currently on display at the Firepower Museum of the Royal Artillery at the former Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in England. The engagement outside Mirbat was intentionally underreported by the Omani and British governments at the time. SAS involvement in Oman was a sensitive issue, and no one wanted undue official attention. SGT Labalaba’s comrades have lobbied ever since that he should posthumously receive the Victoria Cross for his selfless actions in Oman that day.

In October of 2018 Prince Harry formally dedicated a bronze likeness of SGT Labalaba at the Nadi International Airport in Fiji commemorating his exceptional bravery. Another statue occupies a place of honor at SAS HQ as well. Tom Petch, a British filmmaker and himself a former SAS operator is currently producing a feature movie about SGT Labalaba and the Battle of Mirbat.

He’s a senior NCO in the Delta Force. SGM Payne enlisted in 2002, serving as a sniper in the 75th Ranger Regiment until 2007, when he joined the Delta Force.

(SGM Payne in Afghanistan)

In 2015, then-SFC Payne’s unit was deployed to Iraq to help combat ISIS. His unit advised and trained the newly formed Kurdish Counter Terrorist Group. One day, fresh graves are seen outside of a known ISIS prison. The joint team is given the green light.

Payne’s team arrives with the CTG at night time. Upon arrival, they’re hit with volleys of gunfire. The Kurds not having conducted any operations before, are nervous and don’t move forward. The Deltas lead the way, giving their friends courage to press forward. Master Sergeant Joshua Wheeler is killed leading his comrades into battle.

Meanwhile, SFC Payne and his team press into the building. They reach a bolted door that holds in the Iraqi hostages. The team attempts to break it, but there is too much fire coming their way. Payne braves the fire and breaks the bolt. The joint team then starts getting all of the hostages out. As the firefight continues, ISIS terrorists start setting off bomb vests, causing fires which cripple the building’s stability. After securing multiple hostages, they move outside.

(Then-SFC Payne, left or center)

However, plenty of hostages are left. SFC Payne keeps moving back inside to make sure no man is left behind. By doing so, he is risking getting crushed or burnt to death. At one point, a tired hostage believes he is going to die in the fire and can no longer walk to the outside. Payne helps him up and gets him outside.

Overall, due to then-SFC Payne’s actions, over 75 Iraqis are rescued. At first, he is awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest American military award. However, on September 11, 2020, SGM Payne was awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military award in the US.

(President Trump awarding SGM Payne the MoH)

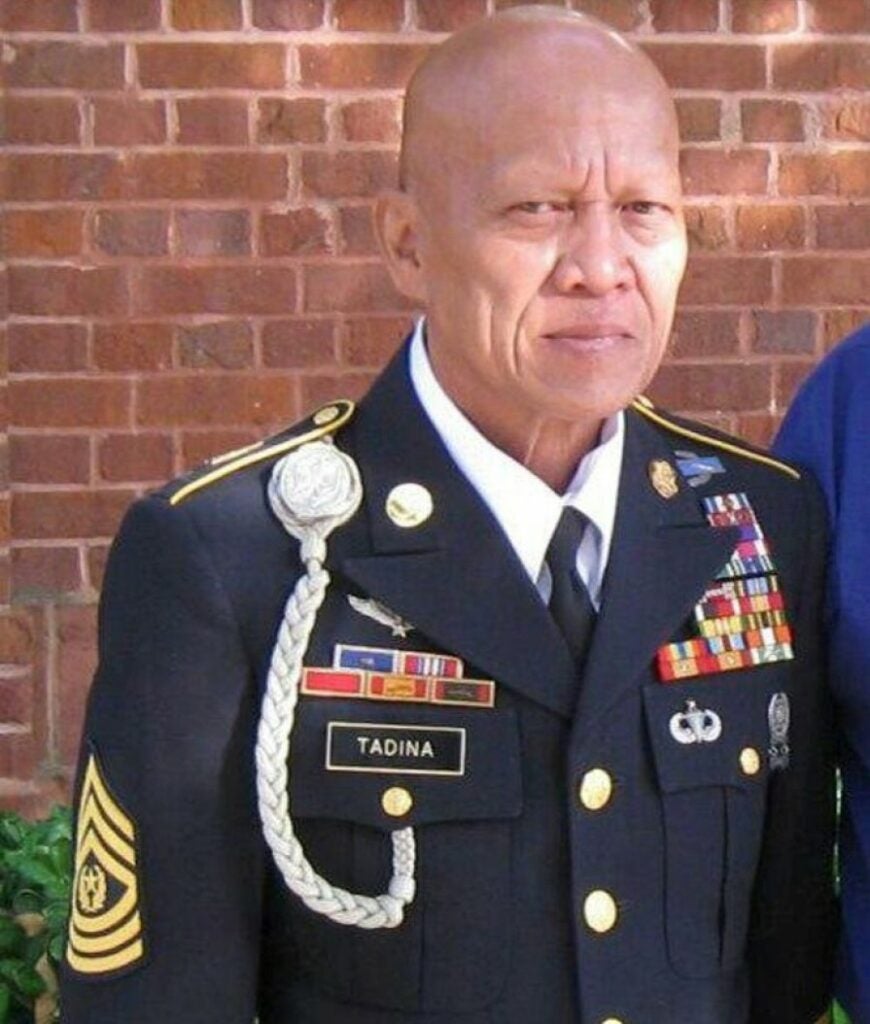

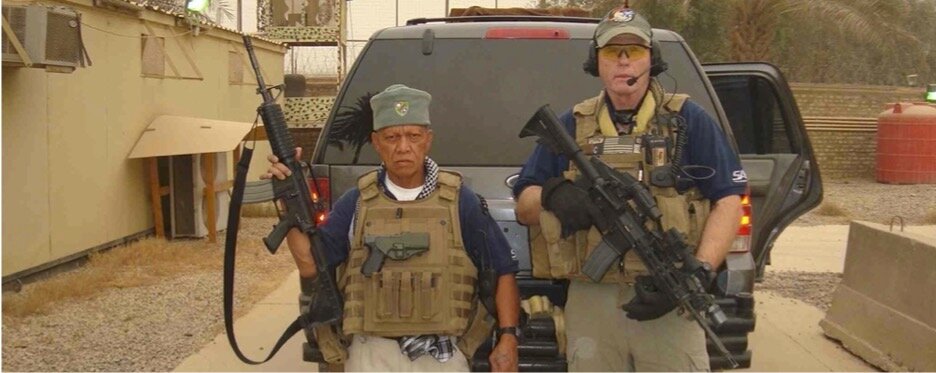

A 30-year Army veteran who was the longest continuously serving Ranger in Vietnam and one of the war’s most decorated enlisted soldiers died. Patrick Gavin Tadina served in Vietnam for over five years straight between 1965 and 1970, leading long-range reconnaissance patrols deep into enemy territory – often dressed in black pajamas and sandals and carrying an AK-47.

The retired Command Sergeant Major Patrick Gavin Tadina died May 29, 2020, in North Carolina. He was 77.

“Early this morning, my Dad … took his last breaths and went to be with all the Rangers before him,” his daughter Catherine Poeschl said on Facebook. “I know they are all there waiting for him.”

He is survived by his wife, two sisters, two daughters, four sons, six grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren, the family, said in a brief online obituary. A funeral had not yet been scheduled.

A native of Hawaii, Tadina earned two Silver Stars, 10 Bronze Stars – seven with valor – three Vietnamese Crosses of Gallantry, four Army Commendation Medals, including two for valor, and three Purple Hearts.

After the second Rambo movie release, Patrick Gavin Tadina was profiled in Stars and Stripes, where he was contrasted with Sylvester Stallone‘s beefy – often shirtless – portrayal of a Vietnam combat veteran.

Patrick Gavin Tadina in the Vietnam War

“The real thing comes in a smaller, less glossy package,” wrote reporter Don Tate in December 1985. “Tadina stands just over 5-feet-5and swells all the way up to 130 pounds after a big meal.” His small stature and dark complexion helped him pass for a Viet Cong soldier on patrols deep into the Central Highlands, during which he preferred to be in the point position. His citations describe him walking to within feet of enemies he knew to be lying in wait for him and leading a pursuing enemy patrol into an ambush set by his team.

In Vietnam, he served with the 173rd Airborne Brigade Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol, 74th Infantry Detachment Long Range Patrol, and Company N (Ranger), 75th Infantry.

Tadina joined the Army in 1962 and served in the Dominican Republic before going to Southeast Asia. He also served with the 82nd Airborne Division in Grenada during Operation Urgent Fury in 1983 and with the 1st Infantry Division during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

A 1995 inductee into the Ranger Hall of Fame, he served with “extreme valor,” never losing a man during his years as a team leader in Vietnam, a hall of fame profile at Fort Benning said.

Some 200 men had served under him without “so much as a scratch,” said a newspaper clipping his daughter shared, published while Tadina was serving at Landing Zone English in Vietnam’s Binh Dinh province, likely in 1969.

Tadina himself was shot three times, and his only brother was also killed in combat in Vietnam, Stars and Stripes later reported.

The last time he was shot was during an enemy ambush in which he earned his second Silver Star, and the wounds nearly forced him to be evacuated from the country, the LZ English story said.

As the point man, Tadina was already inside the kill zone when he sensed something was wrong, but the enemy did not fire on him, apparently confused about who he was, the article stated. After spotting the enemy, Tadina opened fire and called out the ambush to his teammates before falling to the ground and being shot in both calves.

He refused medical aid and continued to command until the enemy retreated, stated another clipping, quoting from his Silver Star citation.

“When you’re out there in the deep stuff, there’s an unspoken understanding,” he told Tate in 1985. “It’s caring about troops.”

He was not one to boast of his experiences, his daughter said in a phone interview Monday.

After retiring from the Army in 1992, he continued working security jobs until 2013, Poeschl said, including stints in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In recent years, he’d been struggling with dementia and other ailments, she said, and he often believed he was back in the Army with his buddies.

He always seemed most at home with his “Ranger family,” his daughter said. She was trying to get word of his death to as many as she could.

“He was my dad, but he belonged to so many other people,” she said.