Category: Real men

Heroic One Armed Charge in Burma

Talk about getting into your opponents mind before the fun starts!

Young American men will be taught the hard way that selflessness, courage, and their masculine instincts will get them 20 to life in prison.

This week, a brave Marine acted when no one else would to restrain a deranged homeless schizophrenic on a New York City F train who was, by all accounts, terrorizing people and shouting “I’ll hurt anyone on this train.”

“‘I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison,’ screamed the 30-year-old Jordan Neely, who had 44 arrests under his belt and an outstanding warrant for felony assault (he punched an old woman in the face), as he flailed around throwing items of his clothing. ‘I’m ready to die!’ In response, a 24-year-old Marine Corps veteran put Neely in a chokehold, incapacitating him and releasing him after he stopped struggling and passed out,” Inez Stepman wrote.

When Neely died at the hospital, all hell broke loose.

This is not the first time a courageous man minding his own business has put himself in danger to protect others. It’s happened many times, in fact. Toxic masculinity has saved more lives than penicillin.

But in this case, the erratic lunatic was black, the courageous restrainer was not just white but blond and handsome, and worst of all: the lunatic shuffled off this mortal coil when he arrived at the hospital.

Inevitably, the left’s muscle memory of how politically lucrative George Floyd’s 2020 death was for them kicked in. The Floyd Playbook could be run!

AOC fired up her Twitter and called his death a “murder.” Al Sharpton is polishing his diamond cufflinks before his press conference. Neely’s cousins are getting fitted for new suits before their Oval Office visit. Nancy Pelosi has already ordered the solid gold casket and white horse-drawn carriage for the funeral, which will be held after Neely lies in state in the Capitol. Kente cloth scarves are being passed out in the Old Executive Office Building. Kamala Harris’s speechwriter is ripping nitrous balloons as he crafts her eulogy. The whole band is getting back together!

Weakness Is Strength. Courage Is Hatred

In the aftermath, I tweeted this: “Strong men brave enough to intervene publicly when a deranged lunatic is terrifying people are going to be rounded up first; this is brilliant strategy for the Regime. Pick off the bravest and most selfless heroes first. Leave the cowards behind, who will fall in line fast.”

The worse the subway Viking’s fate is, the less likely any of us, the sane ones, will be tempted to lift a finger when they come for us, our friends, or our neighbors. If the Viking gets 20 years on Riker’s Island, plus some prison rapes and beatings for good measure as the guards look the other way — that’ll teach you boys a lesson.

Since literally the morning the first European settlers set foot in the new country, the ethos drilled into American men is to be strong, be brave, and be prepared to protect and defend your family, your homestead, and your fellow man. This is what men are for, after all. This is why God made them stronger than women. Those biceps are not just for deadlifting. Their main purpose is twofold: wielding a spear for the hunt, and wielding your fists or a sword for defense.

It feels like Good Samaritan laws have gone in and out of favor over time in America. For many years after 9/11, no able-bodied man boarded an airplane without first preparing himself to tackle a terrorist if he had to. Does that happen anymore? Or would the passengers laugh and whip out their phones as the terrorist slit a flight attendant’s throat? You will not go to jail for watching someone beat another person to death as you stream it live on social media. That’s perfectly acceptable now, even encouraged.

But every normal man I know would be unable to stand and watch a psycho assaulting an innocent stranger. My future husband once threw the first punch in a bloody fistfight against a much larger, much drunker man who was persistently harassing me and getting in my face late at night outside a bar in New York City. (My husband won, so I married him soon after.)

You Won’t Get In Trouble for Being a Coward

As an avid Twitter user, I probably see a dozen graphic videos a week of men doing the opposite: standing idly by, shouting approval and laughing, cameras out, as violent individuals assault, beat, rape, and shoot innocent strangers. This violence is almost exclusively black-on-white, or black-on-Asian.

In April, such a video made national news: a terrified young woman in downtown Chicago is knocked down and stomped on by a large mob during a “teen takeover” of the city. Where are all the videos showing the white-on-black and white-on-Asian stompings? I’m sure if they existed, AOC herself would be tweeting them out 24/7.

In this terrible, ugly, upside-down, zero-trust society I’ve been forced to raise a family in, I have developed new survival rules. I have instructed my husband and son to be cowards. That’s right: to do nothing if they are in a situation where a dangerous psycho is threatening violence to a stranger.

I have begged them to sit on their hands; to be one of the people who just watches, runs away, or calls 911. It goes against every chivalric instinct in their bodies, but I do not want them dead or in jail. Instead of being hailed as heroes for saving some old lady’s life, they would be tried as killers and put away for life.

My teenage son informed me he won’t go along with my surrender monkey ethos and is prepared to defend himself and others if he has to. This is a dangerous virtue for a boy to have in a blue city in 2023! Does he want his mother to get gray hair? Doesn’t he know how much good hair colorists cost these days?

I have failed as a mother because I forgot to teach my sons to be cowards.

This week’s watershed event on the New York City F train illustrates the blackpilling utility of my new rules. “Son, you see that damsel in distress over there getting her teeth kicked out by that filthy homeless man? You just sit tight and get off at the next stop and tell the nearest social worker. It’s not your problem.”

Podcaster Aimee Terese tweeted: “A man threatening the safety of everyone else in a tiny, highly populated, contained space, is a liability to himself and to others. The marine is a hero, and we need more men like him, which is why the left is wetting the bed about it. They don’t want that ethos to catch on.”

Courage and Nobility Will Be Punished

Neely was lynched by a racist and this racist will be made an example of. This is a teaching moment for Democrats — young American men will be taught the hard way that nobility, selflessness, courage, and their masculine instinct to defend the innocent are bad. Don’t be like this former Marine!

Mohammed Atta’s immortal words to the doomed passengers of American Airlines Flight 11 were “Just stay quiet and you’ll be okay.” Of course, it only applies to some of us. The raving maniacs on our subways, in our parks, and on our buses are free to live their best lives.

Democrat politicians have made forced passivity the new rule for normal people out in public. We are all cuckolds now. After all, what other sane choice do we have?

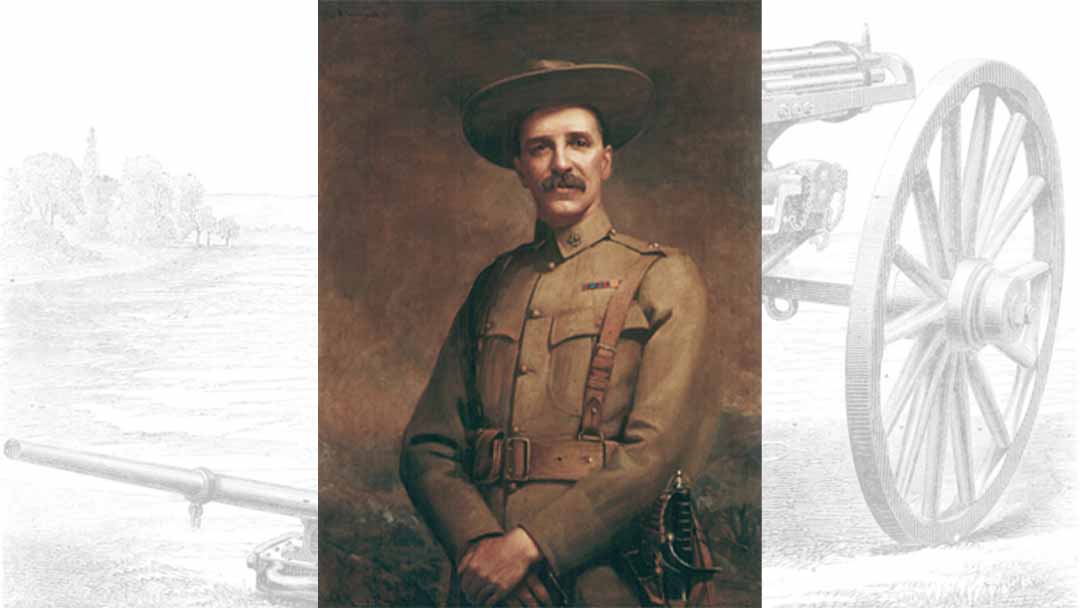

Arthur L. “Gat” Howard earned his reputation and nickname from behind a Gatling gun.

As slang for a gun, “gat” took hold in the early 20th century, but is clearly a play on Gatling gun, designed in 1862 and named after its inventor Richard J. Gatling.

Born in 1846, Howard served with the U.S. Cavalry for five years and fought in the Indian Wars on the western plains before going to work for Winchester Arms. Eventually he left Winchester and started his own cartridge manufacturing company and enjoyed some success before the factory burned down. Howard served in the Connecticut National Guard where he led the Gatling gun platoon, but it was in service of the Canadian government where Howard earned his nickname.

A Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3 single action revolver with pearl grips attributed to Howard is on offer in Rock Island Auction’s Feb. 14-17 Sporting & Collector Auction along with an unmarked black powder reproduction Model 1862 Gatling gun.

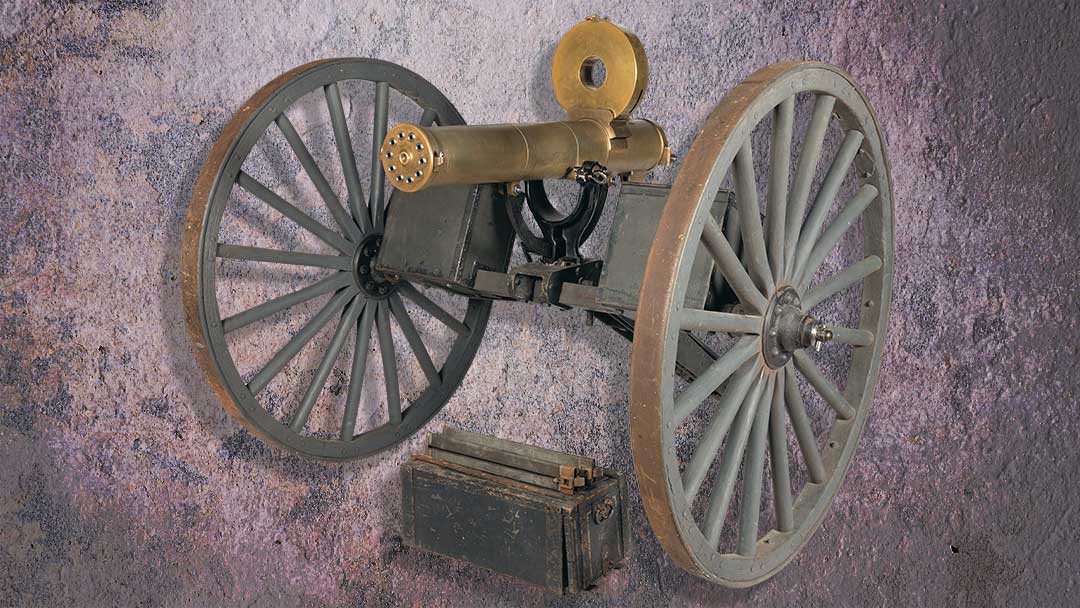

Gatling Gun

Gatling, a doctor, invented his namesake weapon hoping to make a gun that would reduce the number of men in battle and lower the devastating losses seen early in the American Civil War. A precursor to the machine gun, Gatling’s multi-barrel, crank-operated weapon was patented in 1862 but not officially adopted by the U.S. military until 1866, after the end of the Civil War.

Colt produced all Gatling guns for the U.S. market from 1866 to 1903. The grandfather of the machine gun, the first Gatling gun could fire about 200 rounds per minute. Later models achieved the fire rate of as high as 1,500 rounds per minute. The 1883 Colt Gatling gun had a full brass housing and a fire rate of 800 rounds per minute.

The Gatling gun available in the February Sporting & Collector Auction is an unmarked black powder reproduction of the Model 1862 which did not use self-contained cartridges as we know them today. It utilized steel cartridge chambers which were individually loaded with paper cartridges in the front and primed with percussion caps at the rear.

Rebellion in Canada

In 1885, rebellion was fomenting north of the border as indigenous people and mixed race settlers were unhappy about European settlers coming west, the Canadian government’s neglecting to recognize land titles in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and being under-represented in the Canadian parliament.

The Canadian government at the time had a small professional army and so enlisted militias to assist in quelling the uprising, amassing a military force of about 5,000 soldiers. Colt executives seeing a marketing opportunity, offered to loan a Gatling gun to the Canadian government.

The question was who would operate the Gatling gun? Colt and Gatling turned to Howard. He was not to be a representative of Colt, nor the Connecticut National Guard. Even Gatling stated that Howard didn’t represent him but was on the mission as “a friend of the gun.”

Gatling saw Howard, two of his guns, likely 10-barrel 1874 models, and 5,000 rounds of ammunition get on a train bound for Winnipeg. There was little time to train Canadian gunners.

In an early battle during the uprising, the Battle of Cut Knife Hill, the resistance gained the upper hand so it was up to a Gatling gun operated by a Canadian gunner to cover a retreat by government forces, preventing a possible massacre. Howard, as always wearing his blue army uniform, played a key part in stopping a charge in the decisive Battle of Batoche in May 1885 that ended the five month-long rebellion. Ultimately, it was the superior firepower of the government forces that led to the end of the resistance.

Canada after the Rebellion

Howard earned $5,000 and received a medal for his role in quashing the rebellion. He never returned to Connecticut, instead taking up residence in Montreal where he became an investor in the Dominion Cartridge Factory. Along with the stipend and medal, Howard also got assistance from the Canadian government that allowed him to import materials for the cartridge factory duty free. The business made him a wealthy man.

His actions gained Howard enough fame that his purported death and survival in a storm off Nova Scotia was reported by The New York Times. He grew weary of the tedium of Montreal and as the Boer War began in South Africa, he offered to commission a battery of four machine guns at his expense but was refused. Instead, he was offered and accepted a position as machine gun officer in the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles.

Second Boer War

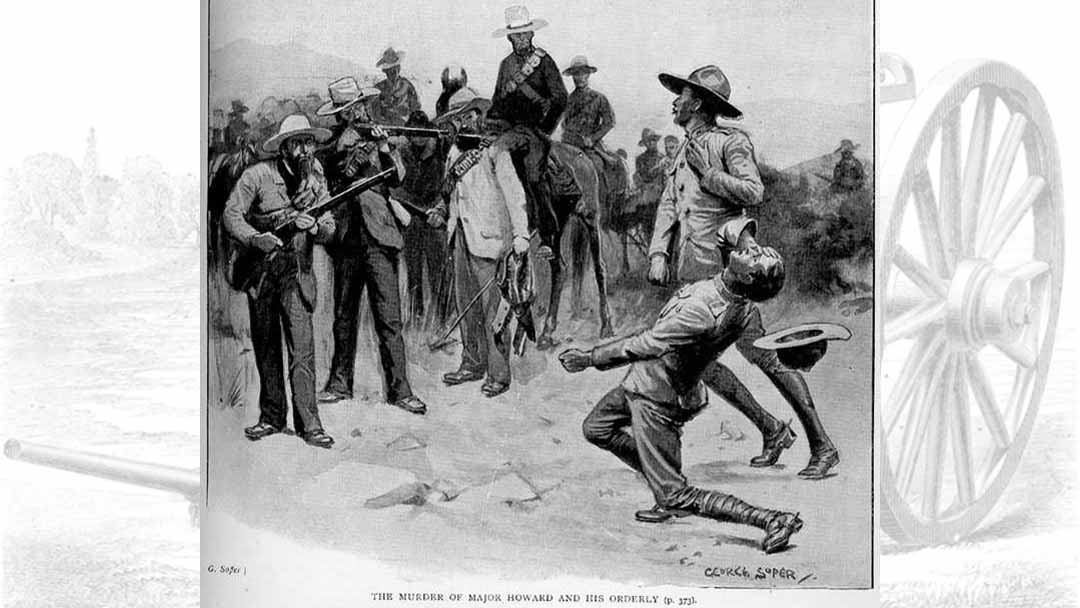

Conflict between the descendants of South African Dutch settlers, called Boers or Afrikaners, and British colonists exploded into open warfare in 1899. The British took control of most of the territory as the Boers began fighting with guerilla tactics.

In South Africa, Howard commanded a Maxim and Colt machine gun. An aggressive and fearless leader willing to fight at close quarters, he didn’t return to Canada with his unit in December, 1900, choosing to stay in South Africa where he organized the Canadian Scouts, equipped with air-cooled Colt Model 1895 machine guns.

Two months later, in February, 1901, Howard was killed at the age of 57. Reports of Howard’s death varied, with some saying he and his aide were killed in an ambush by Boers, or that they were captured and murdered. In a short article in The New York Times, he was described as “an intrepid and absolutely fearless fellow.”

The article also stated “He knew a machine gun perfectly and it was his skill in handling the gun of the Gatling make that earned for him his title during the Riel rebellion when he was in the Canadian Service.”

Machine Gun Hero

Arthur L. “Gat” Howard was a man of action who joined in the Canadian government’s effort to put down a western uprising, earned his reputation and nickname as a Gatling gunner. An American who remained in Canada, Howard fought in the Boer War where he met his death. A Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3 with pearl grips and attributed to Howard is on offer in the Feb. 14-17 Sporting & Collector Auction, as is a Gatling gun Model 1862 black powder reproduction of the weapon that ushered in the machine gun.

Sources:

“A Connecticut Yankee (and his Gatling) in Queen Victoria’s Canada,” by Terry Edwards,Small Arms Re

The Navy SEAL Who Went to Ukraine Because He Couldn’t Stop Fighting

Daniel Swift was in his element waging America’s war on terror from Afghanistan to Yemen. After his marriage failed back home, he found a new purpose: killing Russians.

by By Ian Lovett and Brett Forrest

Daniel Swift’s nerves were shot. By the start of 2019, his Navy SEAL colleagues said, he was hardly eating or sleeping.

He had separated from his wife. A court had barred him from seeing his four children, and he was facing legal charges for false imprisonment and domestic battery.

Mr. Swift told fellow SEALs in San Diego, where he was based, that he was planning to go to Africa to fight wildlife poachers. They brushed off the comment, convinced that Mr. Swift, a soldier’s soldier, would never abandon his post.

A week later, he disappeared. Navy investigators searched for him, but Mr. Swift was always a step ahead.

He resurfaced in March of last year when he slipped into a group messaging chat of current and former SEALs. He was now fighting Russians in Ukraine, he texted. He petitioned the group for supplies, and later invited members to join him on the front lines. None did. Some advised him to come home. Others marveled as word of his exploits spread.

Mr. Swift was among thousands of young men who flooded to Kyiv from the West, including American veterans of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many said they were drawn to the cause of a democratic country resisting a larger autocratic one.

But there was another side to Mr. Swift’s quest, as revealed in interviews with his colleagues and a memoir he published online under a pseudonym. Mr. Swift was part of a large group who spent years fighting America’s war on terror and have struggled to settle back into civilian life.

The military has acknowledged the impact on servicemembers and their families, particularly special forces, who suffered the outsized casualties during the later years of the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

Long deployments have pushed up divorce rates, while suicides among special forces spiked to the highest in the military. The government has launched programs to help lessen the psychological burden on spouses as well as troops.

Daniel Glenn, a psychologist who works with veterans at the University of California, Los Angeles, said many tell him that the U.S. military does a great job preparing them to go to war, but not to return from it.

“They’ve been in some of the most intense, dangerous, awful situations. They’re really good at that,” he said. “Comparatively, back in the civilian world, everything feels mundane. It’s hard to have anything that feels like a rush or makes you feel alive.”

Daniel Swift serving in Severodonetsk, Ukraine.

Many of the men who fought with Mr. Swift said this feeling was part of what drew them to Ukraine.

“A lot of people won’t admit it, but lots of people are here because war is fun,” said a 43-year-old U.S. Army veteran. Civilian life, he added, didn’t offer the same camaraderie or sense of purpose: “War is easy in many ways. Your mission is crystal clear. You’re here to take the enemy out.”

‘Viet Dan’

Mr. Swift had wanted to be a Navy SEAL since childhood. After graduating from high school in rural Oregon in 2005, he married his high-school sweetheart and enlisted in the Navy.

Two years later, he enrolled in the SEALs selection program, a grueling process highlighted by “Hell Week,” when candidates train physically for more than 20 hours a day, run more than 200 miles and sleep for about four hours total.

The vast majority of candidates wash out. Mr. Swift, just 20 years old, made it. Soon after, his wife gave birth to their first child.

A teetotaler, Mr. Swift sometimes drove fellow SEALs on bar crawls, though he often stayed in and studied tactics in military manuals.

On deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, he won a reputation for dependability, a rare Legion of Merit award and a nickname, “Viet Dan,” inspired by his fondness for action.

“Tough kid, humble, quiet, and a little bit crazy,” said a SEAL who was the third in command of Mr. Swift’s first platoon.

In 2013, when his wife was pregnant with their fourth child, Mr. Swift decided to quit. “I thought maybe God was trying to tell me to settle down and be a family man,” he wrote in his memoir, which he self-published in 2020.

He joined the Washington state police and reveled in time off with his kids, exploring logging roads through the woods, cooking hot dogs and shooting guns.

The new job didn’t suit him, though. Police officers were rewarded for giving out tickets rather than helping people, he wrote in his book. Sitting in his cruiser scanning for speeders, Mr. Swift texted friends in the SEALs and told them he missed life among them, according to Navy comrades.

In 2015, a friend from the SEALs died, and Mr. Swift decided to re-enlist as a fight with Islamic State beckoned. “I wanted my piece of the pie,” he wrote.

In Iraq again, Mr. Swift took on Islamic State militants in city streets. Later, he deployed to Yemen.

Navy SEAL candidates train during ‘Hell Week.’ PHOTO: PETTY OFFICER 1ST CLASS ABE MCNATT/U.S. NAVY

Most candidates wash out of the SEALs selection program. PHOTO: PETTY OFFICER 1ST CLASS ABE MCNATT/U.S. NAVY

The overseas missions took a toll on his marriage. In October 2018, shortly after Mr. Swift returned from seven months in Yemen, his relationship with his wife collapsed.

In court documents, Maegan Swift said he’d returned home angry, prone to yelling at her. He disputed this account in his book, but both agreed that one night when they were arguing at home, she threatened to call the police if he prevented her from leaving with the kids.

Mr. Swift went to the bedroom and returned with a pistol.

He said in the book that it was unloaded and that he told her: “See what happens when the cops try and take my children from me.”

Ms. Swift moved the children to her sister’s house while Mr. Swift was traveling. When he returned, a scuffle ensued as he tried to put his younger daughter in his car and Ms. Swift and her sister tried to stop him. Mr. Swift said he was fending off the women as they attacked him; they said he choked Ms. Swift’s sister. The police arrived and arrested him.

Ms. Swift declined to comment for this article.

A Navy psychologist said Mr. Swift had adjustment disorder, a term for difficulty re-entering civilian life, Mr. Swift wrote in his memoir. He dismissed the diagnosis.

Mr. Swift was charged in state court with false imprisonment, child endangerment and domestic battery, which threatened his military career. If convicted of a felony, Mr. Swift would lose his right to carry a gun, and this prospect shook him, according to SEALs who knew him. Being a warrior was nearly all he’d known.

Most of all, he worried about losing his kids, the oldest of whom was the oldest of whom was 11.

Mr. Swift wrote that while the U.S. government has helped veterans cope with war trauma, “what we don’t seem to care about is when they return home to things they’ve been fighting for, only to have them ripped away.”

“I have been face to face with death multiple times, and it has never been more traumatic than having my children taken away,” he wrote.

In the early months of 2019, Mr. Swift disappeared. His passport pinged at immigration control in Mexico, then in Germany, a former SEAL colleague said.

Mr. Swift tried to join the French Foreign Legion, according to another SEAL colleague, but was rejected because the recruiters worried his kids could be a distraction. He ended up in Thailand where he fought kickboxing matches and taught English.

He wrote his memoir, he said, to explain himself to his children. “If you ever want to talk to me just make a Facebook page,” he wrote, addressing his kids. “I look.”

He titled the book “The Fall of a Man.”

No retreat

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February of last year, news reports of the war’s child victims reminded Mr. Swift of his own children and stirred him to action, he later told friends.

He entered Ukraine in early March and joined a platoon running missions behind enemy lines near Kyiv, according to soldiers who fought with him there.

During his first operations, he taped body armor to his chest under a white Fruit of the Loom T-shirt because he arrived without a vest to hold bulletproof plates. His teammates called it the “Dan special.”

Conducting reconnaissance and hunting armored vehicles with a Javelin antitank missile, he soon developed a reputation as highly skilled, methodical and most comfortable in the middle of a firefight, according to men who fought with him.

Adam Thiemann, a former U.S. Army Ranger, recalled one mission, where he and Mr. Swift set off with five others to ambush a Russian barrack. Outside the compound, they surprised a handful of uniformed Russian soldiers and quickly killed them. The Ukrainian commander ordered a retreat. Mr. Swift, who’d been quiet up to that point, was incredulous.

“Retreat?” Mr. Swift said, according to Mr. Thiemann and another team member. “We didn’t even get shot at.”

When Russian troops pulled back from Kyiv at the end of March, many foreign fighters went home, feeling they’d helped fend off the existential threat to Ukraine. Mr. Swift stayed.

His foreign legion team—a unit of Ukraine’s military intelligence, made up of about 20 foreigners and a Ukrainian commander—was dispatched to the city of Mykolaiv in the country’s south.

There, Mr. Swift led the squad on aquatic missions, often using inflatable boats to travel across open sea at night to target Russian positions, according to several soldiers in his unit.

During down time, teammates said, he was quiet and uncommonly disciplined. He didn’t drink or smoke, and worked out obsessively. Even near the front, he’d go out for long solo runs.

Men fighting with Mr. Swift in Ukraine said he would accompany them for shawarma in Mykolaiv, walking around shirtless in jeans and sandals and getting waitresses’ phone numbers. In photos, he rarely smiled; he was more likely to crack a joke during missions, they said.

He told only a few comrades about his life outside the military.

One teammate, a 29-year-old American who goes by the call sign Tex, said Mr. Swift confided in him about his troubles at home.

“He loved his kids,” Tex said. “A lot of things didn’t bother Dan. But the thought of his kids maybe being told who he was and not actually knowing him, that worried him.”

Ukrainian soldiers in the eastern city of Bakhmut in January. PHOTO: EMANUELE SATOLLI FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In early June, the team headed to the eastern city of Severodonetsk, which the Russians were flattening with artillery.

The group had earned a reputation for taking on missions that others turned down. As the situation in Severodonetsk grew worse, Mr. Swift joked that if they were surrounded, at least they could shoot in every direction.

On its last trip into the city, the team tried to hit a building where they believed about 10 Russians were hiding. As soon as they fired the first rocket, however, they found themselves under heavy assault. Dozens of Russians were in the building. Mr. Swift ended up trapped in a corner, trading machine-gun fire with a Russian.

The legion team’s Ukrainian commander, Oleksiy Chubashev, was shot through the neck.

With a Russian tank approaching, Mr. Swift laid down covering fire to free a group of pinned-down comrades, who put Capt. Chubashev on a stretcher and carried him out the back of the building.

Mr. Swift joined them outside to help carry the stretcher. A video seen by The Wall Street Journal shows them hauling the body through the city in daylight, without cover, while artillery shells whistle and crash around them.

After about a half a mile in the June heat, an exhausted young soldier dropped his corner of the stretcher.

“Dan just tore into him,” a member of the team from Minnesota recalled. “He never yells. But he screamed, like, ‘What are you saving your energy for?’ ”

Capt. Chubashev died before making it back to base.

The next morning, Mr. Swift sat down beside several teammates who were drinking coffee. He said he was thinking about calling his children.

The men were shocked. They didn’t know he had kids.

Soon after, Ukrainian forces started to retreat from Severodonetsk. Several of the men on Mr. Swift’s team decided they’d had enough. They went home.

‘I’ll walk out’

Mr. Swift, by contrast, began setting up for life in Ukraine. He was looking for an apartment in Kyiv and sorted out a Ukrainian visa for a Thai woman he’d met when he was living there. He spoke of establishing an academy in Ukraine after the war to teach military tactics.

He returned to Mykolaiv, where he again led aquatic missions into Russian-held territory.

In August, Mr. Swift led an attack on a Russian-held village across the Inhulets River. Working with Ukrainian special forces, the team forced the Russians to retreat, calling in a strike on a house full of enemy soldiers and taking seven prisoners.

But they ended up sheltering in a basement under Russian artillery fire. Mr. Swift called the unit’s new Ukrainian commander, asking to pull back, according to team members. The commander said no.

Mr. Swift pulled the team out anyway. In the middle of the night, he and the team medic swam upriver to retrieve a half-inflated boat to bring their comrades and gear back across to Ukrainian-held territory. When they got back to the base, Mr. Swift quit and moved to another foreign legion team.

A spokesman for Ukraine’s foreign legion declined to comment.

By the new year, Ukraine’s hold on Bakhmut, in the eastern Donetsk region, was tenuous. Mr. Swift’s unit, dispatched there, found Ukrainian troops scattered in basements around the city sheltering from withering Russian artillery fire.

“I’m just here in the basement,” Mr. Swift said in a phone call with a former Green Beret, who’d fought with him earlier in the war. “Trying to plan missions that are not going to get us killed.”

Mr. Swift was scheduled to leave Bakhmut later in January and planned to meet the Thai woman in Romania and bring her to Kyiv.

On the night of Jan. 17, Mr. Swift led a small team of Western fighters into a cluster of homes and began clearing them of fighters from the Russian paramilitary group Wagner, according to Mr. Swift’s unit commander. As Mr. Swift led his squad between buildings, a Russian soldier fired a rocket-propelled grenade.

A projectile, either shrapnel or a bullet, penetrated Mr. Swift’s helmet and lodged in his brain.

His commander found Mr. Swift lying prone, yet coherent. As the unit hurried to evacuate, Mr. Swift fought to remain lucid and asked for help getting to his feet. “I’ll walk out,” he said.

He lost consciousness and died three days later at a trauma center in Dnipro, a nearby regional capital. He was 35 years old.

A memorial service for Daniel Swift in Lviv, Ukraine. PHOTO: STANISLAV IVANOV/GLOBAL IMAGES UKRAINE/GETTY IMAGES

Mr. Swift died while still a SEAL, though AWOL, in a war to which the U.S. hasn’t committed troops. This has complicated his family’s effort to collect benefits from Washington.

A Navy spokesman said Mr. Swift was considered to be an active deserter at the time of his death, and that “we cannot speculate as to why the former Sailor was in Ukraine.” The Pentagon has yet to make a ruling on the family’s petition.

On Feb. 11, several SEALs attended Mr. Swift’s funeral in Oregon. In a video viewed by the Journal, one by one they punched metal SEAL pins into the surface of his casket, a SEAL ritual to the fallen.

Nikita Nikolaienko contributed to this article.