Carlos Hathcock at work in the fields of Vietnam. (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps)

Long before Chris Kyle penned “American Sniper,” Carlos Hathcock was already a legend.

He taught himself to shoot as a boy, just like Alvin York and Audie Murphy before him.

He had dreamed of being a U.S. Marine his whole life and enlisted in 1959 at just 17 years old.

Hathcock was an excellent sharpshooter by then, winning the Wimbledon Cup shooting championship in 1965, the year before he would deploy to Vietnam and change the face of American warfare forever.

He deployed in 1966 as a military policeman, but immediately volunteered for combat and was soon transferred to the 1st Marine Division Sniper Platoon, stationed at Hill 55, South of Da Nang.

This is where Hathcock would earn the nickname “White Feather” — because he always wore a white feather on his bush hat, daring the North Vietnamese to spot him — and where he would achieve his status as the Vietnam War’s deadliest sniper in missions that sound like they were pulled from the pages of Marvel comics.

White Feather vs. The General

Early morning and early evening were Hathcock’s favorite times to strike. This was important when he volunteered for a mission he knew nothing about.

“First light and last light are the best times,” he said. “ In the morning, they’re going out after a good night’s rest, smoking, laughing. When they come back in the evenings, they’re tired, lollygagging, not paying attention to detail.”

He observed this first hand, at arm’s reach, when trying to dispatch a North Vietnamese Army General officer.

For four days and three nights, he low crawled inch by inch, a move he called “worming,” without food or sleep, more than 1500 yards to get close to the general. This was the only time he ever removed the feather from his cap.

“Over a time period like that you could forget the strategy, forget the rules and end up dead,” he said. “I didn’t want anyone dead, so I took the mission myself, figuring I was better than the rest of them, because I was training them.”

Hathcock moved to a treeline near the NVA encampment.

“There were two twin .51s next to me,“ he said. “I started worming on my side to keep my slug trail thin. I could have tripped the patrols that came by.”

The general stepped out onto a porch and yawned. The general’s aide stepped in front of him and by the time he moved away, the general was down, the bullet went through his heart. Hathcock was 700 yards away.

“I had to get away. When I made the shot, everyone ran to the treeline because that’s where the cover was.” The soldiers searched for the sniper for three days as he made his way back. They never even saw him.

“Carlos became part of the environment,” said Edward Land, Hathcock’s commanding officer. “He totally integrated himself into the environment. He had the patience, drive, and courage to do the job. He felt very strongly that he was saving Marine lives.”

With 93 confirmed kills – his longest was at 2,500 yards – and an estimated 300 more, for Hathcock, it really wasn’t about the killing.

“I really didn’t like the killing,” he once told a reporter. “You’d have to be crazy to enjoy running around the woods, killing people. But if I didn’t get the enemy, they were going to kill the kids over there.”

Saving American lives is something Hathcock took to heart.

Carlos Hathcock, in camp (left), and ready to go out on a kill mission (right).

“The Best Shot I Ever Made”

“She was a bad woman,” Carlos Hathcock once said of the woman known as ‘Apache.’

“Normally kill squads would just kill a Marine and take his shoes or whatever, but the Apache was very sadistic. She would do anything to cause pain.”

This was the trademark of the female Viet Cong platoon leader. She captured Americans in the area around Carlos Hathcock’s unit and then tortured them without mercy.

“I was in her backyard, she was in mine. I didn’t like that,” Hathcock said. “It was personal, very personal. She’d been torturing Marines before I got there.”

In November of 1966, she captured a Marine Private and tortured him within earshot of his own unit.

“She tortured him all afternoon, half the next day,” Hathcock recalls. “I was by the wire… He walked out, died right by the wire.”

Apache skinned the private, cut off his eyelids, removed his fingernails, and then castrated him before letting him go. Hathcock attempted to save him, but he was too late.

Carlos Hathcock had had enough. He set out to kill Apache before she could kill any more Marines.

One day, he and his spotter got a chance. They observed an NVA sniper platoon on the move. At 700 yards in, one of them stepped off the trail and Hathcock took what he calls the best shot he ever made.

“We were in the midst of switching rifles. We saw them,” he remembered. “I saw a group coming, five of them. I saw her squat to pee, that’s how I knew it was her. They tried to get her to stop, but she didn’t stop. I stopped her. I put one extra in her for good measure.”

Women were a regular part of the Viet Cong, like the evil torturer “The Apache”

A Five-Day Engagement

One day during a forward observation mission, Hathcock and his spotter encountered a newly minted company of NVA troops. They had new uniforms, but no support and no communications.

“They had the bad luck of coming up against us,” he said. “They came right up the middle of the rice paddy. I dumped the officer in front, my observer dumped the one in the back.”

The last officer started running the opposite direction.

“Running across a rice paddy is not conducive to good health,” Hathcock remarked. “You don’t run across rice paddies very fast.”

NVA and Viet Cong troops in action somewhere in Vietnam.

According to Hathcock, once a Sniper fires three shots, he leaves. With no leaders left, after three shots, the opposing platoon wasn’t moving.

“So there was no reason for us to go either,” said the sniper. “No one in charge, a bunch of Ho Chi Minh’s finest young go-getters, nothing but a bunch of hamburgers out there.”

Hathcock called artillery at all times through the coming night, with flares going on the whole time.

When morning came, the NVA were still there.

“We didn’t withdraw, we just moved,” Hathcock recalled. “They attacked where we were the day before. That didn’t get far either.”

White Feather and The M2

Though the practice had been in use since the Korean War, Carlos Hathcock made the use of the M2 .50 caliber machine gun as a long-range sniper weapon a normal practice. He designed a rifle mount, built by Navy Seabees, which allowed him to easily convert the weapon.

M25 rifle

“I was sent to see if that would work,” he recalled. “We were elevated on a mountain with bad guys all over. I was there three days, observing. On the third day, I zeroed at 1,000 yards, longest 2,500. Here comes the hamburger, came right across the spot where it was zeroed, he bent over to brush his teeth and I let it fly. If he hadn’t stood up, it would have gone over his head. But it didn’t.”

The distance of that shot was 2,460 yards – almost a mile and a half – and it stood as a record until broken in 2002 by Canadian sniper Arron Perry in Afghanistan.

White Feather vs. The Cobra

“If I hadn’t gotten him just then,” Hathcock remembers, “he would have gotten me.”

Many American snipers had a bounty on their heads. These were usually worth one or two thousand dollars. The reward for the sniper with the white feather in his bush cap, however, was worth $30,000.

Like a sequel to Enemy at The Gates, Hathcock became such a thorn in the side of the NVA that they eventually sent their own best sniper to kill him. He was known as the Cobra and would become Hathcock’s most famous encounter in the course of the war.

“He was doing bad things,” Hathcock said. “He was sent to get me, which I didn’t really appreciate. He killed a gunny outside my hooch. I watched him die. I vowed I would get him some way or another.”

That was the plan. The Cobra would kill many Marines around Hill 55 in an attempt to draw Hathcock out of his base.

“I got my partner, we went out we trailed him. He was very cagey, very smart. He was close to being as good as I was… But no way, ain’t no way ain’t nobody that good.”

In an interview filmed in the 1990s, He discussed how close he and his partner came to being a victim of the Cobra.

“I fell over a rotted tree. I made a mistake and he made a shot. He hit my partner’s canteen. We thought he’d been hit because we felt the warmness running over his leg. But he’d just shot his canteen dead.”

Eventually the team of Hathcock and his partner, John Burke, and the Cobra had switched places.

“We worked around to where he was,” Hathcock said. “I took his old spot, he took my old spot, which was bad news for him because he was facing the sun and glinted off the lens of his scope, I saw the glint and shot the glint.” White Feather had shot the Cobra just moments before the Cobra would have taken his own shot.

“I was just quicker on the trigger otherwise he would have killed me,” Hathcock said. “I shot right straight through his scope, didn’t touch the sides.”

With a wry smile, he added: “And it didn’t do his eyesight no good either.“

1969, a vehicle Hathcock was riding in struck a landmine and knocked the Marine unconscious. He came to and pulled seven of his fellow Marines from the burning wreckage. He left Vietnam with burns over 40 percent of his body. He received the Silver Star for this action in 1996.

Lieutenant General P. K. Van Riper, Commanding General Marine Corps Combat Development Command, congratulates Gunnery Sgt. Carlos Hathcock (Ret.) after presenting him the Silver Star during a ceremony at the Weapons Training Battalion. Standing next to Gunnery Sgt. Hathcock is his son, Staff Sgt. Carlos Hathcock, Jr.

After the mine ended his sniping career, he established the Marine Sniper School at Quantico, teaching Marines how to “get into the bubble,” a state of complete concentration. He was in intense pain as he taught at Quantico, suffering from Multiple Sclerosis, the disease that would ultimately kill him — something the NVA could never accomplish.

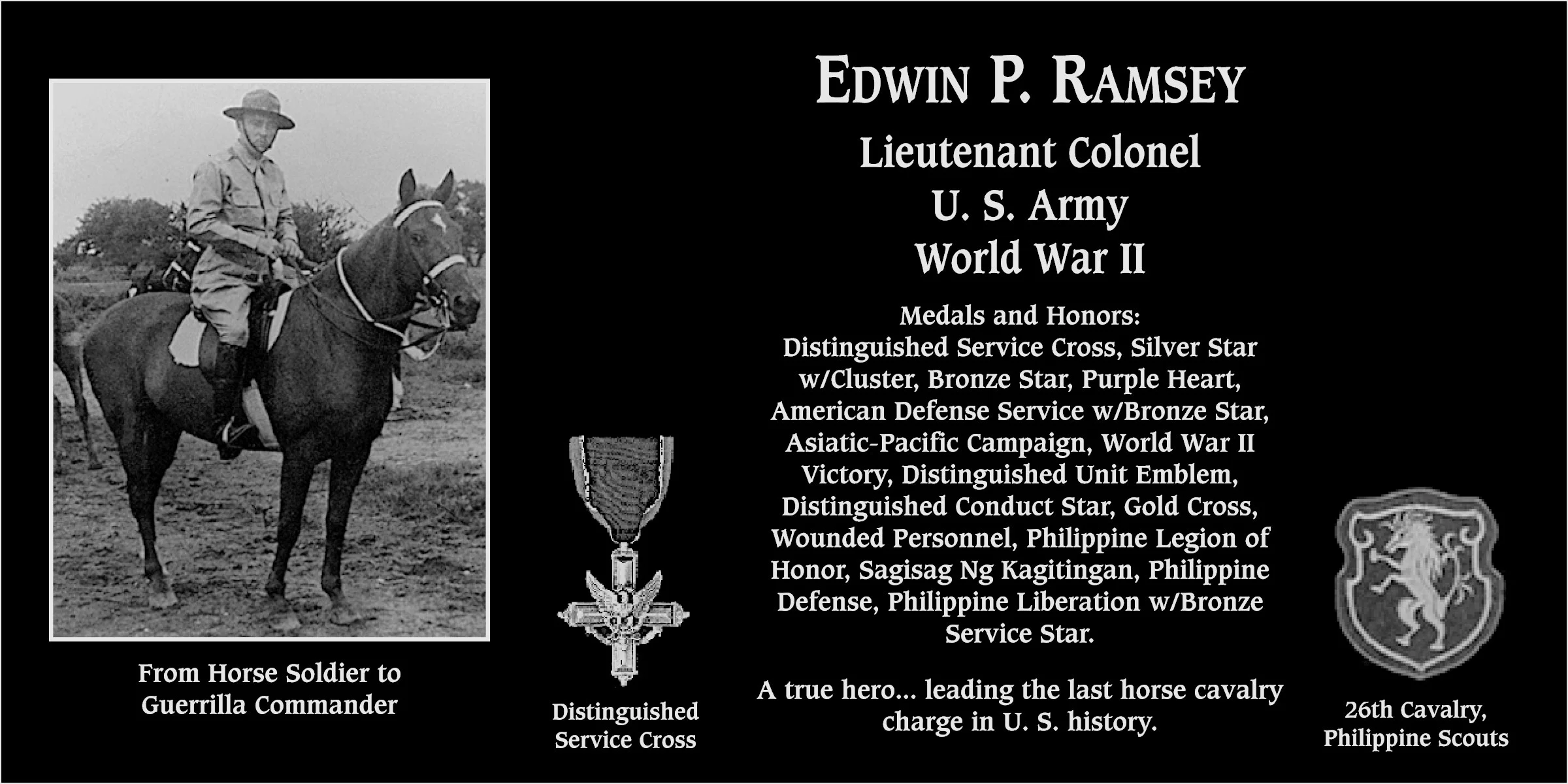

Ramsey quickly signaled his men to deploy into forager formation. Then he raised his pistol and shouted, “Charge!” With troops firing their pistols, the galloping cavalry horses smashed into the surprised enemy soldiers, routing them.

Ramsey quickly signaled his men to deploy into forager formation. Then he raised his pistol and shouted, “Charge!” With troops firing their pistols, the galloping cavalry horses smashed into the surprised enemy soldiers, routing them.

.JPG)