This article is about the writer. For other people named Mencken, see

Mencken (surname).

| H. L. Mencken |

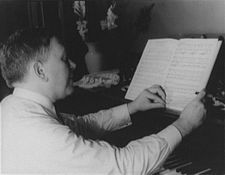

H. L. Mencken in 1928

|

| Born |

Henry Louis Mencken

September 12, 1880

Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died |

January 29, 1956 (aged 75)

Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Occupation |

Journalist, satirist, critic |

| Notable credit(s) |

The Baltimore Sun |

| Spouse(s) |

Sara Haardt |

| Relatives |

August Mencken, Jr.

Brother |

| Family |

August Mencken, Sr.

Father |

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, satirist, cultural critic and scholar of American English.[1]Known as the “Sage of Baltimore”, he is regarded as one of the most influential American writers and prose stylists of the first half of the twentieth century. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians and contemporary movements. His satirical reporting on the Scopes trial, which he dubbed the “Monkey Trial”, also gained him attention.

As a scholar, Mencken is known for The American Language, a multi-volume study of how the English language is spoken in the United States. As an admirer of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, he was a detractor of religion, populism and representative democracy, which he believed to be a system in which inferior men dominated their superiors.[2]Mencken was a supporter of scientific progress, skeptical of economic theories and critical of osteopathic and chiropractic medicine.

Mencken opposed American entry into World War I and World War II. His diary indicates that he was a racist and anti-semite, and privately used coarse language and slurs to describe various ethnic and racial groups (though he believed it was in poor taste to use such slurs publicly).[3]Mencken also at times seemed to show a genuine enthusiasm for militarism, though never in its American form. “War is a good thing,” he once wrote, “because it is honest, it admits the central fact of human nature… A nation too long at peace becomes a sort of gigantic old maid.”[4]

Mencken’s longtime home in the Union Square neighborhood of West Baltimore was turned into a city museum, the H. L. Mencken House. His papers were distributed among various city and university libraries, with the largest collection held in the Mencken Room at the central branch of Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library.[citation needed]

Early life[edit]

Mencken was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 12, 1880. He was the son of Anna Margaret (Abhau) and August Mencken, Sr., a cigar factory owner. He was of German ancestry and spoke German in his childhood.[5] When Henry was three, his family moved into a new home at 1524 Hollins Street facing Union Square park in the Union Squareneighborhood of old West Baltimore. Apart from five years of married life, Mencken was to live in that house for the rest of his life.[6]

In his best-selling memoir Happy Days, he described his childhood in Baltimore as “placid, secure, uneventful and happy.”[7]

When he was nine years old, he read Mark Twain‘s Huckleberry Finn, which he later described as “the most stupendous event in my life”.[8] He became determined to become a writer and read voraciously. In one winter while in high school he read Thackeray and then “proceeded backward to Addison, Steele, Pope, Swift, Johnson and the other magnificos of the Eighteenth century”. He read the entire canon of Shakespeare and became an ardent fan of Kipling and Thomas Huxley. As a boy, Mencken also had practical interests, photography and chemistry in particular, and eventually had a home chemistry laboratory in which he performed experiments of his own devising, some of them inadvertently dangerous.[10]

He began his primary education in the mid-1880s at Professor Knapp’s School, located on the east side of Holliday Street between East Lexington and Fayette Streets, next to the Holliday Street Theatre and across from the newly constructed Baltimore City Hall. The site today is the War Memorial and City Hall Plaza laid out in 1926 in memory of World War I dead. At fifteen, in June 1896, he graduated as valedictorian from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. BPI was a mathematics, technical and science-oriented public high school, founded in 1883, which was then located on old Courtland Street just north of East Saratoga Street. This location is today the east side of St. Paul Street in St. Paul Place and east of Preston Gardens.

He worked for three years in his father’s cigar factory. He disliked the work, especially the sales aspect of it, and resolved to leave, with or without his father’s blessing. In early 1898 he took a class in writing at one of the country’s first correspondence schools, the Cosmopolitan University. This was to be the entirety of Mencken’s formal education in journalism, or in any other subject. Upon his father’s death a few days after Christmas in the same year, the business reverted to his uncle, and Mencken was free to pursue his career in journalism. He had applied in February 1899 to the Morning Herald newspaper (which became the Baltimore Morning Herald in 1900) and had been hired as a part-timer there, but still kept his position at the factory for a few months. In June he was hired as a full-time reporter.

Mencken served as a reporter at the Herald for six years. Less than two and a half years after the Great Baltimore Fire, the paper was purchased in June 1906 by Charles H. Grasty, the owner and editor of The News since 1892, and competing owner and publisher Gen. Felix Agnus, of the town’s oldest (since 1773) and largest daily, The Baltimore American. They proceeded to divide the staff, assets and resources of The Herald between them. Mencken then moved to The Baltimore Sun, where he worked for Charles H. Grasty. He continued to contribute to The Sun, The Evening Sun(founded 1910) and The Sunday Sun full-time until 1948, when he stopped writing after suffering a stroke.

Mencken began writing the editorials and opinion pieces that made his name at The Sun. On the side, he wrote short stories, a novel, and even poetry, which he later revealed. In 1908, he became a literary critic for The Smart Set magazine, and in 1924 he and George Jean Nathan founded and edited The American Mercury, published by Alfred A. Knopf. It soon developed a national circulation and became highly influential on college campuses across America. In 1933, Mencken resigned as editor.

Personal life[edit]

Marriage[edit]

In 1930, Mencken married Sara Haardt, a German American professor of English at Goucher College in Baltimore and an author eighteen years his junior. Haardt had led efforts in Alabama to ratify the 19th Amendment.[12] The two met in 1923, after Mencken delivered a lecture at Goucher; a seven-year courtship ensued. The marriage made national headlines, and many were surprised that Mencken, who once called marriage “the end of hope” and who was well known for mocking relations between the sexes, had gone to the altar. “The Holy Spirit informed and inspired me,” Mencken said. “Like all other infidels, I am superstitious and always follow hunches: this one seemed to be a superb one.”[13] Even more startling, he was marrying an Alabama native, despite his having written scathing essays about the American South. Haardt was in poor health from tuberculosis throughout their marriage and died in 1935 of meningitis, leaving Mencken grief-stricken.[14]He had always championed her writing and, after her death, had a collection of her short stories published under the title Southern Album.

Great Depression, war and after[edit]

During the Great Depression, Mencken did not support the New Deal. This cost him popularity, as did his strong reservations regarding US participation in World War II, and his overt contempt for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He ceased writing for the Baltimore Sun for several years, focusing on his memoirs and other projects as editor, while serving as an adviser for the paper that had been his home for nearly his entire career. In 1948, he briefly returned to the political scene, covering the presidential election in which President Harry S. Trumanfaced Republican Thomas Dewey and Henry A. Wallace of the Progressive Party. His later work consisted of humorous, anecdotal, and nostalgic essays, first published in The New Yorker, then collected in the books Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and Heathen Days.

Last days[edit]

On November 23, 1948, Mencken suffered a stroke, which left him aware and fully conscious but nearly unable to read or write and able to speak only with difficulty. After his stroke, Mencken enjoyed listening to Classical music and, after some recovery of his ability to speak, talking with friends, but he sometimes referred to himself in the past tense, as if he were already dead. During the last year of his life, his friend and biographer William Manchester read to him daily.[15]

Preoccupied as Mencken was with his legacy, he organized his papers, letters, newspaper clippings and columns, even grade school report cards. After his death, these materials were made available to scholars in stages in 1971, 1981, and 1991, and include hundreds of thousands of letters sent and received; the only omissions were strictly personal letters received from women.

The H.L. Mencken Club was founded in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania in 2008.[16] The organization was founded by Paul Gottfried, the current president.[17]

Mencken died in his sleep on January 29, 1956.[18] He was interred in Baltimore’s Loudon Park Cemetery.[19]

Though it does not appear on his tombstone, during his Smart Set days Mencken wrote a joking epitaph for himself:

If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.[20]

Man of ideas[edit]

In his capacity as editor and man of ideas, Mencken became close friends with the leading literary figures of his time, including Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Hergesheimer, Anita Loos, Ben Hecht, Sinclair Lewis, James Branch Cabell, and Alfred Knopf, as well as a mentor to several young reporters, including Alistair Cooke. He also championed artists whose works he considered worthy. For example, he asserted that books such as Caught Short! A Saga of Wailing Wall Street (1929), by Eddie Cantor (ghost-written by David Freedman) did more to pull America out of the Great Depression than all government measures combined. He also mentored John Fante. Thomas Hart Bentonillustrated an edition of Mencken’s book Europe After 8:15.

Mencken also published many works under various pseudonyms, including Owen Hatteras, John H Brownell, William Drayham, WLD Bell, and Charles Angoff.[21] As a ghostwriter for the physician Leonard K. Hirshberg, he wrote a series of articles and (in 1910) most of a book about the care of babies.

Mencken admired German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (he was the first writer to provide a scholarly analysis in English of Nietzsche’s views and writings) and Joseph Conrad. His humor and satire owe much to Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain. He did much to defend Dreiser despite freely admitting his faults, including stating forthrightly that Dreiser often wrote badly and was a gullible man. Mencken also expressed his appreciation for William Graham Sumner in a 1941 collection of Sumner’s essays, and regretted never having known Sumner personally. In contrast, Mencken was scathing in his criticism of the German philosopher Hans Vaihinger, whom he described as “an extremely dull author” and whose famous book Philosophy of ‘As If’ he dismissed as an unimportant “foot-note to all existing systems.”[22]

Mencken recommended for publication libertarian philosopher and author Ayn Rand‘s first novel, We the Living, calling it “a really excellent piece of work.” Shortly afterward, Rand addressed him in correspondence as “the greatest representative of a philosophy” to which she wanted to dedicate her life, “individualism,” and later listed him as her favorite columnist.[23]

For Mencken, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was the finest work of American literature. Much of that book relates how gullible and ignorant country “boobs” (as Mencken referred to them) are swindled by con men like the (deliberately) pathetic “Duke” and “Dauphin” roustabouts with whom Huck and Jim travel down the Mississippi River. These scam-artists swindle by posing as enlightened speakers on temperance (to obtain the funds to get roaring drunk), as pious “saved” men seeking funds for far off evangelistic missions (to pirates on the high seas, no less), and as learned doctors of phrenology (who can barely spell). Mencken read the novel as a story of America’s hilarious dark side, a place where democracy, as defined by Mencken, is “the worship of jackals by jackasses.”

Such turns of phrase evoked the erudite cynicism and rapier sharpness of language displayed by Bierce in his darkly satiric Devil’s Dictionary. A noted curmudgeon,[24] democratic in subjects attacked, Mencken savaged politics,[25]hypocrisy, and social convention. Master of English, he was given to bombast, once disdaining the lowly hot dog bun’s descent into “the soggy rolls prevailing today, of ground acorns, plaster of paris, flecks of bath sponge and atmospheric air all compact.”[26]

As a nationally syndicated columnist and book author, he commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians and contemporary movements, such as the temperance movement. Mencken was a keen cheerleader of scientific progress but very skeptical of economic theories and critical of osteopathic/chiropractic medicine.

As a frank admirer of Nietzsche, Mencken was a detractor of populism and representative democracy, which he believed was a system in which inferior men dominated their superiors.[2] As did Nietzsche, he also spoke out against religious belief (and as a fervent nonbeliever, against the very notion of a deity), particularly Christian fundamentalism, Christian Science and creationism, and against the “Booboisie,” his word for the ignorant middle classes.[27][28][29] In the summer of 1925, he attended the famous Scopes “Monkey Trial” in Dayton, Tennessee, and wrote scathing columns for the Baltimore Sun (widely syndicated) and American Mercury mocking the anti-evolution Fundamentalists (especially William Jennings Bryan). The play Inherit the Wind is a fictionalized version of the trial, and, as noted above, the cynical reporter E.K. Hornbeck is based on Mencken. In 1926, he deliberately had himself arrested for selling an issue of The American Mercury that was banned in Boston under the Comstock laws.[30] Mencken heaped scorn not only on the public officials he disliked, but also on the contemporary state of American elective politics itself.

In the summer of 1926, Mencken followed with great interest the Los Angeles grand jury inquiry into the famous Canadian-American evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. She was accused of faking her reported kidnapping and the case attracted national attention. There was every expectation Mencken would continue his previous pattern of anti-fundamentalist articles, this time with a searing critique of McPherson. Unexpectedly, he came to her defense, identifying various local religious and civic groups which were using the case as an opportunity to pursue their respective ideological agendas against the embattled Pentecostal minister.[31] He spent several weeks in Hollywood, California, and wrote many scathing and satirical columns on the movie industry and the southern California culture. After all charges had been dropped against McPherson, Mencken revisited the case in 1930 with a sarcastically biting and observant article. He wrote that since many of that town’s residents acquired their ideas “of the true, the good and the beautiful” from the movies and newspapers, “Los Angeles will remember the testimony against her long after it forgets the testimony that cleared her.”[32]

In 1931 the Arkansas legislature passed a motion to pray for Mencken’s soul after he had called the state the “apex of moronia.”[33]

In the mid 1930s Mencken feared Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal liberalism as a powerful force. Mencken, says Charles A. Fecher, was, “deeply conservative, resentful of change, looking back upon the ‘happy days’ of a bygone time, wanted no part of the world that the New Deal promised to bring in.”[34]

The striking thing about Mencken’s mind is its ruthlessness and rigidity … Though one of the fairest of critics, he is the least pliant. … [I]n spite of his skepticism, and his frequent exhortations to hold his opinion lightly, he himself has been conspicuous for seizing upon simple dogmas and sticking to them with fierce tenacity … true skeptics … see both truth and weakness in every case.

Theology: An effort to explain the unknowable by putting it into terms of the not worth knowing

Racism and elitism[edit]

In addition to his identification of races with castes, Mencken had views about the superior individual within communities. He believed that every community produced a few people of clear superiority. He considered groupings on a par with hierarchies, which led to a kind of natural elitism and natural aristocracy. “Superior” individuals, in Mencken’s view, were those wrongly oppressed and disdained by their own communities, but nevertheless distinguished by their will and personal achievement, not by race or birth.

In 1989, per his instructions, Alfred A. Knopf published Mencken’s “secret diary” as The Diary of H. L. Mencken. According to an Associated Press story, Mencken’s views shocked even the “sympathetic scholar who edited it,” Charles A. Fecher of Baltimore.[37] There is a club in Baltimore called the Maryland Club which had one Jewish member, and that member died. Mencken said, “There is no other Jew in Baltimore who seems suitable,” according to the article. The diary also quoted him as saying of blacks, in September 1943, that “it is impossible to talk anything resembling discretion or judgment to a colored woman. They are all essentially child-like, and even hard experience does not teach them anything.”

Mencken opposed lynching. For example, he had this to say about a Maryland incident:

Not a single bigwig came forward in the emergency, though the whole town knew what was afoot. Any one of a score of such bigwigs might have halted the crime, if only by threatening to denounce its perpetrators, but none spoke. So Williams was duly hanged, burned and mutilated.

Mencken also wrote: “I admit freely enough that, by careful breeding, supervision of environment and education, extending over many generations, it might be possible to make an appreciable improvement in the stock of the American Negro, for example, but I must maintain that this enterprise would be a ridiculous waste of energy, for there is a high-caste white stock ready at hand, and it is inconceivable that the Negro stock, however carefully it might be nurtured, could ever even remotely approach it. The educated Negro of today is a failure, not because he meets insuperable difficulties in life, but because he is a Negro. He is, in brief, a low-caste man, to the manner born, and he will remain inert and inefficient until fifty generations of him have lived in civilization. And even then, the superior white race will be fifty generations ahead of him.”[38]

Democracy[edit]

Rather than dismissing democratic governance as a popular fallacy or treating it with open contempt, Mencken’s response to it was a publicized sense of amusement. His feelings on this subject (like his casual feelings on many other such subjects) are sprinkled throughout his writings over the years, very occasionally taking center-stage with the full force of Mencken’s prose:

Democracy gives [the beatification of mediocrity] a certain appearance of objective and demonstrable truth. The mob man, functioning as citizen, gets a feeling that he is really important to the world—that he is genuinely running things. Out of his maudlin herding after rogues and mountebanks there comes to him a sense of vast and mysterious power—which is what makes archbishops, police sergeants, the grand goblinsof the Ku Klux and other such magnificoes happy. And out of it there comes, too, a conviction that he is somehow wise, that his views are taken seriously by his betters—which is what makes United States Senators, fortune tellers and Young Intellectuals happy. Finally, there comes out of it a glowing consciousness of a high duty triumphantly done which is what makes hangmen and husbands happy.

This sentiment is fairly consistent with Mencken’s distaste for common notions and the philosophical outlook he unabashedly set down throughout his life as a writer (drawing on Friedrich Nietzsche and Herbert Spencer, among others).[39]

Mencken wrote as follows about the difficulties of good men reaching national office when such campaigns must necessarily be conducted remotely:

The larger the mob, the harder the test. In small areas, before small electorates, a first-rate man occasionally fights his way through, carrying even the mob with him by force of his personality. But when the field is nationwide, and the fight must be waged chiefly at second and third hand, and the force of personality cannot so readily make itself felt, then all the odds are on the man who is, intrinsically, the most devious and mediocre—the man who can most easily adeptly disperse the notion that his mind is a virtual vacuum.

The Presidency tends, year by year, to go to such men. As democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.[40]

Science[edit]

Mencken supported biology and the theory of evolution by Charles Darwin but spoke unfavorably of physics and mathematics. In Charles Angoff’s record, Mencken said:

[Isaac Newton] was a mathematician, which is mostly hogwash, too. Imagine measuring infinity! That’s a laugh.[41]

In response, Angoff said: “Well, without mathematics there wouldn’t be any engineering, no chemistry, no physics.” Mencken responded: “That’s true, but it’s reasonable mathematics. Addition, subtraction, multiplication, fractions, division, that’s what real mathematics is. The rest is baloney. Astrology. Religion. All of our sciences still suffer from their former attachment to religion, and that is why there is so much metaphysics and astrology, the two are the same, in science.”[41]

Elsewhere, he spoke of the nonsense of higher mathematics and “probability” theory, after he read Angoff’s article for Charles S. Peirce in the American Mercury. “So you believe in that garbage, too—theories of knowledge, infinity, laws of probability. I can make no sense of it, and I don’t believe you can either, and I don’t think your god Peirce knew what he was talking about.”[42]

Mencken also repeated these opinions multiple times in articles for the American Mercury. He said mathematics is simply a fiction, compared with individual facts that make up science. In a review for Vaihinger’s The Philosophy of “As If”, he said:

The human mind, at its present stage of development, cannot function without the aid of fictions, but neither can it function without the aid of facts—save, perhaps, when it is housed in the skull of a university professor of philosophy. Of the two, the facts are enormously the more important. In certain metaphysical fields, e.g. those of mathematics, law, theology, osteopathy and ethics—the fiction will probably hold out for many years, but elsewhere the fact slowly ousts it, and that ousting is what is called intellectual progress. Very few fictions remain in use in anatomy, or in plumbing and gas-fitting; they have even begun to disappear from economics.[43]

Mencken repeatedly identified mathematics with metaphysics and theology. According to Mencken, mathematics is necessarily infected with metaphysics because of the tendency of many mathematical people to engage in metaphysical speculation. In a review for A. N. Whitehead’s The Aims of Education, Mencken remarked that despite his agreement with Whitehead’s thesis and approval of his writing style, “now and then he falls into mathematical jargon and pollutes his discourse with equations”, and “[t]here are moments when he seems to be following some of his mathematical colleagues into the gaudy metaphysics which now entertains them”.[44] For Mencken, theology is characterized by the fact that it uses correct reasoning from false premises. Mencken also uses the term “theology” more generally, to refer to the use of logic in science or any other field of knowledge. In a review for both A. S. Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World and Joseph Needham’s Man a Machine, Mencken forcefully ridiculed the use of reasoning to establish any fact in science, because theologians happen to be masters of “logic” and yet are mental defectives:

Is there anything in the general thinking of theologians which makes their opinion on the point of any interest or value? What have they ever done in other fields to match the fact-finding of the biologists? I can find nothing in the record. Their processes of thought, taking one day with another, are so defective as to be preposterous. True enough, they are masters of logic, but they always start out from palpably false premises.[45]

Mencken also wrote a review for Sir James Jeans’s book, The Mysterious Universe, in which he said that mathematics is not necessary for physics. Instead of mathematical “speculation” (such as quantum theory), Mencken believed physicists should just directly look at individual facts in the laboratory like chemists:

If chemists were similarly given to fanciful and mystical guessing, they would have hatched a quantum theory forty years ago to account for the variations that they observed in atomic weights. But they kept on plugging away in their laboratories without calling in either mathematicians or theologians to aid them, and eventually they discovered the isotopes, and what had been chaos was reduced to the most exact sort of order.[46]

In the same article which he later re-printed in the Mencken Chrestomathy, Mencken primarily contrasts what real scientists do, which is to simply directly look at the existence of “shapes and forces” confronting them instead of (such as in statistics) attempting to speculate and use mathematical models. Physicists and especially astronomers are consequently not real scientists, because when looking at shapes or forces, they do not simply “patiently wait for further light”, but resort to mathematical theory. There is no need for statistics in scientific physics, since one should simply look at the facts while statistics attempts to construct mathematical models. On the other hand, the really competent physicists do not bother with the “theology” or reasoning of mathematical theories (such as in quantum mechanics):

[Physicists] have, in late years, made a great deal of progress, though it has been accompanied by a considerable quackery. Some of the notions which they now try to foist upon the world, especially in the astronomical realm and about the atom, are obviously nonsensical, and will soon go the way of all unsupported speculations. But there is nothing intrinsically insoluble about the problems they mainly struggle with, and soon or late really competent physicists will arise to solve them. These really competent physicists, I predict, will be too busy in their laboratories to give any time to either metaphysics or theology. Both are eternal enemies of every variety of sound thinking, and no man can traffic with them without losing something of his good judgment.[46]

Mencken also ridiculed Einstein’s theory of general relativity, saying “in the long run his curved space may be classed with the psychosomatic bumps of Gall and Spurzheim”.[47] In his private letters, he said:

It is a well known fact that physicists are greatly given to the supernatural. Why this should be I don’t know, but the fact is plain. One of the most absurd of all spiritualists is Sir Oliver Lodge. I have the suspicion that the cause may be that physics itself, as currently practised, is largely moonshine. Certainly there is a great deal of highly dubious stuff in the work of such men as Eddington.[48]

Anglo-Saxons[edit]

Mencken countered the arguments for Anglo-Saxon superiority prevalent in his time in a 1923 essay entitled “The Anglo-Saxon”, which argued that if there was such a thing as a pure “Anglo-Saxon” race, it was defined by its inferiority and cowardice. “The normal American of the ‘pure-blooded’ majority goes to rest every night with an uneasy feeling that there is a burglar under the bed and he gets up every morning with a sickening fear that his underwear has been stolen.”[49]

In the 1930 edition of Treatise on the Gods, Mencken wrote:

The Jews could be put down very plausibly as the most unpleasant race ever heard of. As commonly encountered, they lack many of the qualities that mark the civilized man: courage, dignity, incorruptibility, ease, confidence. They have vanity without pride, voluptuousness without taste, and learning without wisdom. Their fortitude, such as it is, is wasted upon puerile objects, and their charity is mainly a form of display.[50]

That passage was removed from subsequent editions at his express direction.[51]

Author Gore Vidal later deflected claims of anti-Semitism against Mencken:

Far from being an anti-Semite, Mencken was one of the first journalists to denounce the persecution of the Jews in Germany at a time when The New York Times, say, was notoriously reticent. On November 27, 1938, Mencken writes (Baltimore Sun), “It is to be hoped that the poor Jews now being robbed and mauled in Germany will not take too seriously the plans of various politicians to rescue them.” He then reviews the various schemes to “rescue” the Jews from the Nazis, who had not yet announced their own final solution.[52]

As Germany gradually conquered Europe, Mencken attacked President Roosevelt for refusing to admit Jewish refugees into the United States and called for their wholesale admission:

There is only one way to help the fugitives, and that is to find places for them in a country in which they can really live. Why shouldn’t the United States take in a couple hundred thousand of them, or even all of them?[53]

However, Jewish historian Michael Kazin accused Mencken of being “a lifelong anti-Semite with a reverence for German culture so strong it blinded him to the menace of Nazism.”[54]

Memorials[edit]

Mencken’s home at 1524 Hollins Street in Baltimore’s Union Square neighborhood, where he lived for sixty-seven years before his death in 1956, was bequeathed to the University of Maryland, Baltimore on the death of his younger brother, August, in 1967. The City of Baltimore acquired the property in 1983, and the H. L. Mencken House became part of the City Life Museums. It has been closed to general admission since 1997, but is opened for special events and group visits by arrangement.

Shortly after World War II, Mencken expressed his intention of bequeathing his books and papers to Baltimore‘s Enoch Pratt Free Library. At his death, it was in possession of most of the present large collection. As a result, his papers as well as much of his personal library, which includes many books inscribed by major authors, are held in the Library’s Central Branch on Cathedral Street in Baltimore. The original third floor H. L. Mencken Room and Collection housing this collection was dedicated on April 17, 1956. The new Mencken Room, on the first floor of the Library’s Annex, was opened in November 2003.

The collection contains Mencken’s typescripts, newspaper and magazine contributions, published books, family documents and memorabilia, clipping books, large collection of presentation volumes, file of correspondence with prominent Marylanders, and the extensive material he collected while he was preparing The American Language.

Other Mencken related collections of note are at Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Princeton University, Johns Hopkins University, and Yale University. In 2007, Johns Hopkins acquired “nearly 6,000 books, photographs and letters by and about Mencken” from “the estate of an Ohio accountant.”[55]

The Sara Haardt Mencken collection at Goucher College includes letters exchanged between Haardt and Mencken and condolences written after her death. Some of Mencken’s vast literary correspondence is held at the New York Public Library. “Gift of HL Mencken 1929” is stamped on the Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Luce 1906 edition of William Blake, which shows up from the Library of Congress online version for reading.

- George Bernard Shaw: His Plays (1905)

- The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1907)

- The Gist of Nietzsche (1910)

- What You Ought to Know about your Baby (Ghostwriter for Leonard K. Hirshberg) (1910)

- Men versus the Man: a Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist and H. L. Mencken, Individualist(1910)

- Europe After 8:15 (1914)

- A Book of Burlesques (1916)

- A Little Book in C Major (1916)

- A Book of Prefaces (1917)

- In Defense of Women (1918)

- Damn! A Book of Calumny (1918)

- The American Language (1919)

- Prejudices (1919–27)

- First Series (1919)

- Second Series (1920)

- Third Series (1922)

- Fourth Series (1924)

- Fifth Series (1926)

- Sixth Series (1927)

- Selected Prejudices (1927)

- Heliogabalus (A Buffoonery in Three Acts) (1920)

- The American Credo (1920)

- Notes on Democracy (1926)

- Menckeneana: A Schimpflexikon (1928) – Editor

- Treatise on the Gods (1930)

- Making a President (1932)

- Treatise on Right and Wrong (1934)

- Happy Days, 1880–1892 (1940)

- Newspaper Days, 1899–1906 (1941)[56]

- A New Dictionary of Quotations on Historical Principles from Ancient and Modern Sources (1942)

- Heathen Days, 1890–1936 (1943)

- Christmas Story (1944)

- The American Language, Supplement I (1945)

- The American Language, Supplement II (1948)

- A Mencken Chrestomathy (1949)

Posthumous collections

- Minority Report (1956)

- On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe (1956)

- Cairns, Huntington, ed. (1965), The American Scene.

- The Bathtub Hoax and Blasts & Bravos from the Chicago Tribune (1958)

- Lippman, Theo jr, ed. (1975), A Gang of Pecksniffs: And Other Comments on Newspaper Publishers, Editors and Reporters.

- Rodgers, Marion Elizabeth, ed. (1991), The Impossible HL Mencken: A Selection of His Best Newspaper Stories.

- Yardley, Jonathan, ed. (1992), My Life As Author and Editor.

- A Second Mencken Chrestomathy (1994)

- Thirty-five Years of Newspaper Work (1996)

- A Religious Orgy in Tennessee: A Reporter’s Account of the Scopes Monkey Trial, Melville House Publishing, 2006.

Chapbooks, pamphlets, and notable essays[edit]

- Ventures into Verse (1903)

- The Artist: A Drama Without Words (1912)

- The Creed of a Novelist (1916)

- Pistols for Two (1917)

- The Sahara of the Bozart (1920)

- Gamalielese (1921)

- “The Hills of Zion” (1925)

- The Libido for the Ugly (1927)