Category: Leadership of the highest kind

For example here is the Big Guy (General George Patton) who is doing some land navigation with his compass it the right way! Note that he is OUTSIDE & FAR AWAY from his tank. So that is its magnetic signature will not f*ck up his compass sighting.

For example here is the Big Guy (General George Patton) who is doing some land navigation with his compass it the right way! Note that he is OUTSIDE & FAR AWAY from his tank. So that is its magnetic signature will not f*ck up his compass sighting.

It was stuff like this & other stuff that made his Armies so much more effective. Like stress on Land Navigation, Marksmanship, Combined Arm Tactics, Communicatiosn, taking care of your gear and your troops. etc etc. No wonder why the German High Command always rated him as their most dangerous opponent!

I just hope that Valhalla is as much fun as the Old timers say for him! Anyways thanks sir for terminating with extreme prejudice so many of our Foes in your time.

Grumpy

John Wayne’s departure for a three week

tour in Vietnam in the Spring of 1966 was just

what you’d expect from old Duke’s modest

sense of deprecatory humor, when he told

reporters, “I can’t sing or dance, but I can

sure shake a lot of hands and share a bunch

of cold beers with our boys there.”

He did just that, then stayed another four

weeks on his own dime and time. Therein is

the real story of John Wayne in Vietnam.

Hollywood lore is the stuff of legend, especially when it involves iconic actor John Wayne, best known for

playing macho soldiers or western characters in more than 250 films

before his death in 1979. However, his real-life military involvement is

what had people talking in 1966 during the height of the Vietnam War.

Thanks to the USO’s tireless efforts, celebrities have visited and

cheered American soldiers since 1941. However, Wayne’s visit was

different. The U.S. Department of Defense contracted Wayne for the

three-week tour of Vietnam. According to Wayne, he would be “going

around the hinterlands to give the boys some personal support.”

John Wayne’s Vietnam tour had three missions.

One was his good

will visit to cheer American combat troops and their wounded, plus

some serious fact-finding for a movie he had in mind. Also, he

believed in the political necessity of the war.

Wayne said, “It is important that we keep our word on treaties to

protect our allies, a universally unpopular view in peace-loving, pink

Hollywood.”

He felt so strongly about this that he said it was his duty to make a film

that showed why the war was needed. He said that his planned film,

The Green Berets, was “anti-Communist, pro-Saigon and prompted

by the American Left’s anti-war sentiment.”

It was the only major Hollywood film to support the war effort.

Wayne’s son, Patrick, told me of his father’s Vietnam experiences,

“To make a truly realistic, authentic film, My father said he needed

to go to Vietnam personally and meet with the real combat soldiers

who were literally sometimes face to face with the enemy on their

turf….and gain their first-hand experiences. He wanted this film

to feature the Army’s Special Forces guys, the early Marines in

Vietnam and their role in the war…and he wanted to get it right.”

John Wayne’s in-country education began in the spring of 1966,

at age 59, with a visit to the 3rd Battalion 7th Marines at Chu Lai,

where he shook a lot of hands, passed out a lot of good will, cold

beer and also came away with a lot of good Marine field craft.

For the rest of his tour, though, Wayne visited the Army’s Special Forces (SF) camps, especially the ones out in the boonies, far away from REMF Central.

Former SF SSG John E Padgett recalled, “When an SF camp began

construction, the first priority was a strong defensive perimeter. The

very next priority was a heavily fortified team house/club from which

planning and missions originated, often accompanied by copious

supplies of Carlings Black Label and Pabst Blue Ribbon beers. This

was also the guest house for our few welcomed visitors.”

Retired SFC Ken Richter recalled Wayne’s time at the 5th Special

Forces Group, Detachment A-219, Mike Force, Pleiku, saying, “I

remember him in the C-2 bar one evening saying he hoped he could

witness us SF guys kicking Charlie’s ass. He got his wish.”

After his discharge, SFC Richter worked for Wayne as dive master on

his boat, working on a charitable discovery and salvage assignment

for Stanford University. He adds, “John Wayne was a true patriot and

his boat was full of memorabilia from various military units.”

Wayne’s boat, a World War II minesweeper he bought and converted into his private yacht, was named The Wild Goose.

It was

added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Speaking of WWII, there has always been a persistent myth that John

Wayne dodged the wartime draft, which he did not do. He was classified as 3A (head of family) in 1942. In 1943, he requested a change to 1A, which was turned down, through backdoor politics by Republic Pictures.

He persisted and in May of 1944, was re-classified as l-A. Republic Pictures intervened openly against Wayne’s wishes and got his classification changed to 2-A (support of national

interest) in August of 1944.

Some insiders, including family, said that

he always felt guilty about not serving in

WWII and that is what drove him to be so

personally up front about Vietnam.

Thus, John Wayne made stops at Nui

Ba Den to visit the men of A-324 B and

Detachment C-3 at Bien Ha. His stated

goal to his Saigon minders was to spend

time with most of the A and B teams in the

III Corps, soaking up SF background and

accuracy for his film and hoping to boost

the morale of these warriors.

By June 1966, already past his scheduled

departure time, Wayne made layovers at

Throng Toi and An Lang, where he gathered real and hard experience from the

warriors of A-425. Officers, NCOs and EM

debriefed him on their mission, operational

area and the enemy situation. He was also

shown how the new camp was set up,

including its defenses.

“This was not an easy visit for us,” recalled

former SGT John McGovern, who was one

of Wayne’s guides there. McGovern, a Psy

Ops NCO, recalls, “He wanted to go where

the action was, far away from the flagpole

and the safer sites. Our S-2 knew that the

other side knew he was there and we knew

what a coup it would be if the Cong could

kill the great John Wayne.”

One of Wayne’s guides was SGT Leroy Scott, who told how Wayne’s

helicopter was headed into a Special Forces camp near Pleiku in

the middle of some heavy incoming action, and were warned to

abort landing when two rounds smacked the Huey. SGT Scott adds,

“An immediate 180 occurred.”

This was a larger problem, too, as there was documented intel

that the Republic of North Vietnam’s Soviet mentors, the GRU and

Spetnetz, had already planted the propaganda benefits of Wayne’s

chopper being shot down, his jeep blown up or for a sniper to pick

him off.

John Wayne spent time under fire at the wire plus in the OPs and

LPs. And, of course, he chowed down with the guys. But not every

day in Vietnam was a picnic. Stories abound about the “close calls”

Wayne had. One report mentioned that a Viet Cong sniper’s bullet

narrowly missed him, hitting the ground 50 feet behind him. Wayne

Beer in hand and in his rarely seen reading glasses, The Duke visited the fighting men at SF a Team

323 at Camp Trai Bi in June of ’66. (Jari Salo)

It was a welcoming Jeep delivery of Wayne from the chopper pad at Plei Djerang, with Capt John Kai,

camp CO, at the wheel. Passengers were chopper crew, PIO officer, C-2 officer and The Duke. (Don Briere)

later said to film historian Michael Munn in 1974, “I almost walked

into a sniper’s bullet that had my name on it. I heard the wind of the

bullet whistle past my ear and realized I had had a narrow escape.”

He added later to family members, “Those tough kids of ours over

there have narrow escapes every day, God bless ‘em, ‘cause sometimes they can’t escape getting hit.”

Fortunately, wherever John Wayne would go, for the most part,

good times rode along. From all reports, he had a true and sincere

knack for putting soldiers at ease by signing autographs, taking pictures of them and happily posing for pictures with the guys.

Young Marines called him SGT Stryker, his character’s name in his classic

WWII film, The Sands of Iwo Jima. Men from out of the way firebases threw parties and barbecues in his honor. All agreed that

John Wayne knew how to party and how to work.

4 Sentinel | November 2020

“When he visited us, he brought in both ice

and beer, so we started the day with an

ice chest of cold American beer,” recalled

Retired MAJ John Hyatt, of Wayne’s visit

to A-219. “It was empty when we returned

home at the end of the day.”

Then a first lieutenant with the 281st AHC,

flying support missions for 5th SF units, John

Hyatt recalls John Wayne’s visit to Det C-3,

Bien Hoa, in June. “We had just put A-323 on

the ground at Trai Bi, Tay Ninh, and were taking sporadic fire on the perimeter, and there goes The Duke out to join some of the team

on the line. Helluva man.”

Interestingly, two years later, John Hyatt was at Ft. Rucker flying a camera ship to film some of the scenes for The Green Berets.

Even though Wayne was offered VIP treatment, he visited very remote Special Forces camps, unlike many celebrities, who stayed

comfortable in safer urban zones.

The few others who joined the field troops included

brave USO visitors, the wonderful Donut

Dollies, and the heroic Martha Raye. One of the more amazing “John Wayne in Vietnam” stories centers around the SF A-251 camp at Plei Djereng.

As Wayne made his stop there in June, the camp

allegedly came under attack. Supposedly, everyone was returning fire, including Wayne, who was on an M-60, according to

the tales, which the Internet grew taller than

The Duke himself. Someone was quoted on

at least two blogs saying, “I’m telling ya…

John Wayne was real fuckin’ John Wayne

right with us. He was on top of the TOC

choppin’ Charlie with a 60.” Dramatic, exciting and what you’d expect from The Duke.

But, it’s fiction, not fact.

Special Forces vets

who really were there at the time deny the

story totally, as did Wayne and his family.

Spec4 Donald Briere, who was the camp radio operator then and

who would retire as an SF LTC, said, “There was no raid when Mr

Wayne was there. That nasty raid happened a few days prior to his

arrival. Obviously, the camp was under enemy observation and tension was high. While there, John Wayne did get familiarization with

some of SF’s own special armament.”

As for his dad “chopping Charlie,” son, Patrick, said of the incident,

“Never happened. If it had, he would have told us in grand detail. It

is also a certainty that the military PIO and the Saigon press corps

would have had a field day with it, too.”

For all the stories of fun, heroism and adventure, there are also tales

of sentimentality. Two of these center around bracelets that were

bestowed on Wayne during his time in Vietnam. The first bracelet

was a POW/MIA bracelet that represented the life of CPT Stephen

P. Hanson, USMC. Hanson had sent his wife and son a picture of

himself with the caption “Me as John Wayne.” Sadly, the Marine

was shot down over Laos; he never returned home. Wayne wore his

bracelet to commemorate Hanson. He kept in touch with Hanson’s

wife and son until his own death.

The other memento was a “Yard” bracelet given to him by the Degar

or Montagnard People of Vietnam’s Central Highlands, fighters

against communism. The brass bracelet was a gift from the II CTZ

Mike Force, presented by their Montagnard commander, Ka Doh.

The bracelet is a symbol of friendship and respect. Sentinel editor

Camp Plei Djerang was home to SF Team A-251 during John Wayne’s memorable visit there in 1966. It

is where the reality of then and the internet rumors of today were separated. (Special Forces Association)

Plei Djerang, June 1966, Camp CO Capt John Kai; their guest, John Wayne; SP4 Don Briere; unidentified C-2 officer. (Don Briere)

November 2020 5 | Sentinel

CHURCHILL’S 1911

In May 1915, following the failure of the Allied landings at Gallipoli, Winston Churchill the First Lord of the Admiralty and one of the architects of the landings was sacked. In November he returned to the army, he had graduated from Sandhurst in 1894 and had seen active service in India, Sudan and South Africa. Since 1902 he had been a reserve officer, a major in the yeomanry regiment the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars. On the 20th November, Churchill was attached to the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards to gain experience at the front and to prepare him for command of a brigade.

In December 1915, the Grenadier Guards rotated out of the frontline and Churchill toured nearby French sectors where he was gifted a steel Adrian helmet. Churchill wore this for the rest of his time on active service. The brigade Churchill had hoped for never materialised with Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig willing only to give Churchill command of a battalion.

On 1st January 1916, Churchill was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers replacing Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Northey.

The battalion had taken heavy casualties at the Battle of Loos and was suffering from low morale when he took command. Initially struggling to gain the trust of his officers and men, in part due to his cavalry training he quickly learnt the necessary commands for infantry and learnt how to use all the weapons the battalion was issued with.

During this time Churchill armed himself with a privately purchased American Colt Government Model (or Model 1911) with a specially made custom holster to fit his Sam Browne belt (see image #3). Bought in London, with London proof markings, Churchill had his name engraved onto the right side of the slide.

It is unclear if the pistol was bought by himself or he was given it as a gift. However, he liked the pistol and certainly favoured it over the often carried Webley revolver approved by the army and carried by many officers.

As a wealthy man Churchill had always enjoyed being able to purchase the latest and best campaign equipment. While serving in the Sudan he had carried a Mauser C96 and while in France he had his own water heater brought to the front line and had his wife send him wading boots and a sheepskin lined sleeping bag.

Churchill wearing his French Adrian helmet and possibly armed with his Colt 1911 (source)

When the battalion returned to the frontline Churchill was in his element visiting the trenches three times a day and directing the improvement of his sectors trench fortifications. He frequently came under fire but was said to be calm and collected even when his command post was shelled.

While Churchill commanded the battalion the sector remained quiet and was not called upon to undertake offensive operations. In May 1916 the understrength 6th and 7th battalions of the Royal Scots Fusiliers were ordered to amalgamate with the 7th battalion’s commanding officers taking command. Churchill spent 108 days in command and took this opportunity to return to London and was appointed Minister of Munitions in July 1917.

Churchill himself later said: “I shall always regard this period when I have had the honour to command a battalion of this prestigious regiment (Royal Scots Fusiliers) in the field, as one of the most memorable in my life.”

Sources:

Churchill and War, G. Best (source)

Finest Hour “In The Field” – Churchill and Northey, B. Nanny (source)

Churchill During the Great War (source)

Colt Government Model (civilian, 1911) IWM, (source)

Churchill Rejoins the Ranks, Military History Oct. 2015, B.P. Tolppanen

Commonly known as the father of the modern U.S. Marine Corps sniper program, former NRA Secretary and retired USMC Major Edward James “Jim” Land Jr. has had a life full of significant accomplishments, challenges

and change.

Edward James Land, Jr. was born in 1935 and was raised on a farm in Lincoln, Nebraska. Land graduated at 17 from high school in 1953. He had a full scholarship to the University of Nebraska Agricultural College because of his work on his family farm with soil conservation. “Most of the time when we sat down for a meal, the only thing at the table that didn’t come off the farm was salt and pepper,” said Land. A few days after he graduated high school, Land changed course and enlisted in The Marine Corps.

Planning on serving his country and then using the GI Bill, Land was transferred to Marine Barracks 8th & I which is where he met his wife. They were married and welcomed a daughter while stationed there. Somewhere along the way he changed his plans and wanted to become a Marine Corps officer. He started taking college courses and reenlisted for recruit training to become a Drill Instructor (DI). In 1957, Land went to Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) San Diego for Drill Instructor School and upon completion of their 9-week school became a DI. After 22 months Land was selected for Officer Candidate School (OCS).

After 12 weeks of training at OCS, located at Marine Base Quantico, Land was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant. He had 9 months of training at The Basic School (TBS) and was transferred to the 4th Marine Regiment in Hawaii. After being a platoon commander at Marine Corps Base Hawaii for a year, Land began to grow restless. “Mrs. Land pointed out that I had achieved my goal to become an officer. She said ‘You need a new goal, that’s your problem.’” Land said it made a lot of sense to him since he had always had goals to aspire towards, so he set a new one. To get his college degree.

Land was scheduled to go to Marine Corps Reconnaissance Company that was attached to the Brigade in Hawaii. Before joining Recon Company, he had orders to Panama for Jungle Warfare School. Ten days before his departure, Land was informed by his battalion commander that his orders had been canceled and he was now going to Division Matches. “I had no idea what the division matches were, and I had never shot competitively,” said Land. They won the Pacific Division Match Team Championship his first competition. He was then selected to join the FAF PAC Rifle & Pistol team.

Land worked with CWO Arthur Terry to found the Corps’ first modern sniper course. “We decided you can only give the commanding general so many pot medal trophies…we needed to provide a service,” said Land.

“So we were trying to find something that could provide a service.” Land got the idea from an Army shooter who attended a Canadian sniper school. “So that got me started on the sniper business.”

“My mom used to have a saying ‘If you want to hear God laugh just tell him your plans.’ Because I was going in one direction and he took me somewhere else,” said Land.

Land went to Vietnam as Officer in Charge (OIC) of the 1st Marine Division Sniper Teams. It was in Vietnam that he was the Commanding Officer of legendary Marine Corps sniper, Carlos Hathcock.

After his time in Vietnam, Land was Inspector-Instructor (I&I) for a reserve unit. In 1973 he was sent back to Washington, DC, this time to Headquarters Marine Corps Henderson Hall to be a briefing officer for the Commandant. Due to the high-stress environment of the position, briefing officers were only given a 6-month billet. Land was then assigned as the Marksmanship Coordinator for the Marine Corps, making him responsible for all the marksmanship training across the Corps. Unfortunately, the sniper program had been canceled in 1972. Through his efforts and the help of several fellow Marines, Land managed to get the sniper program started again.

Land was able to reestablish the MOS (military occupational specialty), got the table of organization (TO) and the table of equipment (TE). And finally, the Commandant approved the first permanent Marine Corps Scout Sniper School in Quantico, Virginia. It is still in full operation today.

“The good Lord gave me the contacts that helped me make this possible,” said Land. “I had no idea how to function at that high level of bureaucracy of the Marine Corps. I had many help and guide me along the way.”

When Land retired from the Marine Corps in 1977, he had finally achieved his goal that was set back in Hawaii. He graduated with a Bachelor of Political Science from George Washington University in 1976 and upon his retirement he found himself unemployed and again, without a goal. 6 days later he was hired by the National Rifle Association (NRA), and he would start the second career path that would lead him to be the Secretary of the NRA for 21 years.

In 2015, at the age of 80, he retired from the NRA after being there for 31 years. Shortly after his retirement, his wife of 60 years passed away. “When I was on I&I duty in 1976, I was a Casualty Assistance Officer,” said Land. “I knocked on 211 doors for casualty notifications to families, and one of the things I always told them was not to make any major decisions for at least a year.” He took that advice after his wife, Elly, passed and tried to come up with a new plan.

He purchased a small farm in rural Virginia that he says was “the only thing that kept me going at the time.”

Land starts each day as he always has, with his “plan of the day.” He works on projects out at the farm, hunts and encourages other veterans, many of them his former Marines, to continue living life to the fullest. He has a bucket list of items that he checks off as he completes them and has no plans of slowing down.

Also on his list of projects are motivational sayings that he has come up with and used over the years:

“Establish your priorities and get to work.”

“Nothing will work unless you do.”

“Done is better than perfect.”

He looks at this every day to keep him on track and encourages others to do the same.

Not too bad for a “friendly drill instructor.”

It’s a trope of pirate movies everywhere. Two massive galleons slug it out with their long nines before heaving alongside battered and broken. With masts shattered and rigging in disarray, the two mighty vessels collide like punch-drunk fighters, grapnels spanning the gap as soon as they come within range. Marines, stewards, and able seamen crouch behind the heavy oak with cutlasses and pistols in hand, ready to go. At the Captain’s command, the melee begins.

There’s always somebody who swings Tarzan-fashion from one ship to another amidst sleeting musket fire. As these are movies the injured do not scream for their mothers and those destined to die just fall over without a great deal of fuss. As a species, we have forgotten the details of what happens when two groups of desperate men go at each other with blades. The end result in the real world, particularly onboard an 18th-century Man-o-War with no medical facilities beyond a near-sighted cook with a dirty bone saw, would be gruesome beyond imagining.

The recent Tom Holland epic Uncharted had a variation on that theme that made me want to hurl. In this case, two 16th-century derelict treasure ships once helmed by Ferdinand Magellan are rigged as sling loads beneath these weird twin-rotor Chinook/Skycrane cyborg helicopters. Forget for a moment that the smallest of Magellan’s carracks, the Victoria, weighed 85 tons or 170,000 pounds. Two matching helicopters nonetheless hoist the two supposedly-fragile antique ships out of the Filipino jungle and fly off with them.

There results that same basic ship-to-ship combat set piece only this time it is executed while both vessels are suspended underneath helicopters in flight. Eventually, the Good Guys even use the 500-year-old cannon on one of the ships to shoot down a helicopter. I thought I would be sick. However, it seems not everybody agreed with me. The movie returned $401 million on a $120 million investment and was the fifth-highest-grossing video game movie adaptation of all time. I’m sure we will see sequels until the sun burns out.

While the repel boarders scene in Uncharted indeed savaged credulity, there was an actual exchange on the high seas off the Cape Verde Islands on the evening of May 5, 1943, that was itself pretty darn weird. The epic fight between DE-51, the destroyer escort USS Buckley, and the German U-boat U-66 involved, believe it or not, the weaponization of coffee mugs, empty brass from the American destroyer escort’s deck guns, and a coffee pot. The end result was the last ship-to-ship close-quarters fight in American naval history.

The evening was clear with a bright moon. U-66 was a Type IXC U-boat and the seventh most successful German submarine of the war, having sunk 33 Allied merchant vessels. U-66 was on her ninth war cruise. She had been at sea for four months and was perilously low on fuel. The skipper was Oberleutnant Gehard Seehausen.

Unknown to the Captain and crew of U-66, a US Navy TBM Avenger launched from the American escort carrier USS Block Island on antisubmarine patrol had picked up her radar return and pinpointed the boat’s location some 20 miles from the USS Buckley. The German Kriegsmarine used massive replenishment U-boats called Milk Cows as well as dedicated submarine tenders to resupply their tactical subs with fuel and ordnance while patrolling downrange. On this crisp clear night, U-66 was desperate for a nocturnal rendezvous.

The Buckley’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Brent Able, headed toward the boat’s location at his best possible speed–around 23 knots. It was LCDR Able’s 28th birthday. Seven miles out he picked up the U-boat on his own radar. Presuming a stationary German submarine on the surface was waiting for resupply, LCDR Able took a gamble and approached the German boat boldly hoping the enemy Captain might mistake him for the expected sub tender.

Once within range, the U-boat skipper fired three red flares, the prearranged signal between his boat and their supply ship while under radio silence. Able closed the distance to 4,000 yards before Seehausen realized his mistake. In desperation, the German skipper ordered a torpedo snapshot in the darkness. The crew of the Buckley was not aware of this until they noticed the German fish passing harmlessly off their starboard side. In response, LCDR Able positioned his ship such that the U-boat was silhouetted in the moonlight and opened fire with everything he had.

For the next two minutes, the American destroyer pummeled the surfaced U-boat with withering fire from her 3-inch deck guns, 40mm Bofors, 20mm Oerlikons, and .50-caliber machine guns. High explosive rounds were observed tearing into the conning tower and superstructure of the boat. Seehausen fired another ineffectual torpedo before beginning to maneuver randomly. By now the Buckley had pulled to within twenty yards of the stricken boat. When the geometry was perfect, LCDR Able gave his vessel a hard right rudder and rode the nimble warship up onto the deck of the U-boat. At this point things got real.

The Close Fight

Now realizing their dire straits, the German skipper ordered his men up and on deck. Some attempted to surrender, while others continued the fight. In the bright moonlight, the next ten minutes were unfettered chaos.

The crew of the Buckley had time to prepare for this moment, and the small arms lockers had been emptied. Under the immediate command of the U-boat’s First Officer Klaus Herbig, German sailors began swarming up and onto the forecastle of the destroyer escort. Pintle-mounted .50-calibers and Thompson submachine guns exacted a horrible butcher’s bill, yet the desperate Germans pushed forward still. When the enemy sailors started clambering onto the deck the Americans took it personally.

Two of the attacking enemy were struck in the head with thrown coffee mugs. The crew of the second 3-inch gun was unable to depress the weapon sufficiently to bring effective fire onto the U-boat so they began throwing the heavy empty cases down on the swarming Kriegsmariners. Despite their valiant efforts, five German sailors still managed to make it onboard the American vessel.

The boatswain’s mate responsible for the forward ammunition party came face to face with a German sailor heaving himself over the deck coaming. The American sailor pulled his 1911 pistol and shot the man dead, his body pitching backward and falling into the sea. The Chief Fire Controlman’s duty station was on the bridge, and he had a Thompson. With a clear view of the chaos below he swept the deck of the German boat with long bursts of automatic fire, obtaining what the skipper later described as, “Excellent results.”

One of the rampaging Germans did manage to make it into the wardroom. He was then confronted by a ship’s cook who doused him in hot coffee. The steward proceeded to give the guy a proper pummeling with the coffee pot. At this point, five Germans have accessed the American vessel and LCDR Able wanted some breathing room. He ordered reverse screws and pulled his destroyer escort off of the ventilated U-boat. The five Germans were captured in short order and then escorted below by a sailor armed with a hammer.

The damaged U-boat was still making turns for about 18 knots, so the fight immediately became dynamic yet again. One German attempted to unlimber the U-boat’s main deck gun. Once again per LCDR Able’s after-action report, his body, “disintegrated when struck by four 40mm shells.” As the U-boat scraped along the Buckley’s starboard side a dead-eyed American torpedo man lobbed an armed hand grenade through the open hatch to the U-boat’s conning tower. The Buckley’s gunners continued to rake the enemy ship with quarter-pound high explosive 20mm rounds. Then the GI grenade detonated with a sickening crump within the bowels of the German vessel.

Before the Americans could react, the U-boat veered into the side of the Buckley near the stern. The crushing impact tore a hole in the engine room and sheared off the starboard screw. With flames spouting from the conning tower and multiple cannon holes, the Germans abandoned ship.

The Aftermath

The entire engagement spanned some sixteen minutes. During the course of the fight, the crew of the Buckley expended 300 rounds of .45ACP, sixty rounds of .30-06, thirty rounds of 12-gauge 00 buckshot, and a pair of fragmentation grenades. This is obviously in addition to the dinnerware and coffeepot.

Over the next half hour, the Buckley recovered 36 German sailors, roughly half of the U-boat’s crew. Oberleutnant Seehausen went down with his ship. Despite some not inconsiderable damage, the Buckley returned to Boston under her own power. She was refit and returned to active service in June of 1944. After 23 years on the reserve list, the Buckley was scrapped in 1969.

Oberleutnant Seehausen was posthumously promoted to Kapitainleutnant and awarded the German Cross in Gold in 1944. He already held the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd classes. He was 26 at the time of his death. U-boat service was the most hazardous posting in the German military. Roughly 75% of U-boat crewmen perished before the end of hostilities.

The USS Buckley earned a Navy Unit Citation for the action. LCDR Brent Able was awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second-highest award for valor. Because of the intimate nature of the engagement, the crew of the Buckley was authorized to wear a combat star on their European-African Theater ribbons. The sinking of the German U-boat U-66 was likely the only naval engagement in history to be waged with ammunition drawn from the ship’s galley.

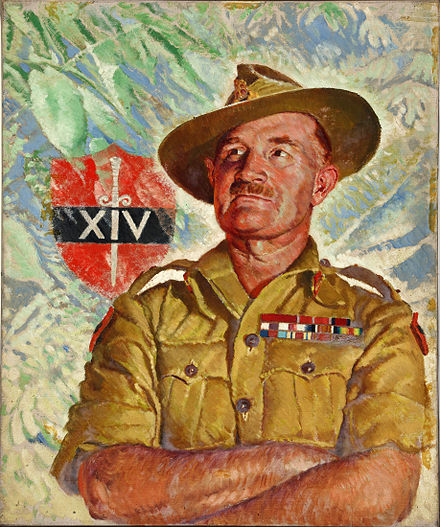

Slim should be remembered as the greatest British general of World War Two.

Even the most sketchily educated Briton today will nevertheless recognise in the murky depths of their consciousness the name of that great British general of World War Two, Montgomery of Alamein. To an older generation perhaps another name resonates equally and perhaps more strongly, the name of a man Montgomery airily dismissed as a mere ‘sepoy general’, and yet someone whose military legacy has arguably outlasted even that of the great ‘Monty’ himself.

That the name of Field Marshal William Slim is remembered by only a few old soldiers and interested military buffs today is a tragedy of enormous proportions, when one assesses in the great weighing scales of history his contribution to Britain’s success in the Second World War and his more longer lasting contribution to the art and science of war as a whole.

The war in the Far East is easy to forget, given that it took place far from home and in the shadow of the titanic struggle against Nazism in Europe. Yet the war against Japan in Burma, India and China was no less titanic, as two competing empires collided violently, with profound implications for the future of the post-war global order, not just in the Pacific but also for the whole of Britain’s creaking empire. Slim played a significant part in the whole story.

Slim was, first and foremost, a born leader of soldiers. It would be inconceivable to think of Monty as ‘Uncle Bernard’, but it was to ‘Uncle Bill’ that soldiers in Burma, from the dark days of 1942 and 1943, through to the great victories over the Japanese in 1944 and 1945, put their confidence and trust.

He inspired confidence because he instinctively knew that the strength of an army lies not in its equipment or its officers, but in the training and morale of its soldiers. Everything he did as a commander was designed to equip his men for the trials of battle, and their interests were always at the forefront of his plans.

He knew them because he was one of them, and had experienced their bitterest trials. Brigadier Bernard Fergusson (later Earl Ballantrae and Governor General of New Zealand), believed that Slim was unlike any other British higher commander to emerge in the Second World War, ‘the only one at the highest level in that war that… by his own example inspired and restored its self-respect and confidence to an army in whose defeat he had shared.’

Not for him the aristocratic or privileged middle class upbringing of some many of his peers, but an early life of industrial Birmingham, relieved only by the opportunities presented for advancement by the upheavals of the First World War. The 100 day 1000 mile retreat from Burma to India in 1942, the longest in the long history of the British Army was, whilst a bitter humiliation, nevertheless not a rout, in large part because Slim was put in command of the fighting troops.

He managed the withdrawal through dust bowl, jungle and mountain alike so deftly that the Japanese, though undoubtedly victorious, were utterly exhausted and unable to mount offensive operations into India for a further year. In time Slim was given the opportunity no British soldier has been given since the days of Wellington: the chance to train an army from scratch and single-handedly mould it into something of his own making, an army of extraordinary spirit and power against which nothing could stand.

By 1945 Slim’s 14th Army, at 500,000 men the largest ever assembled by Britain, had decisively and successively defeated two formidable Japanese armies, the first in Assam in India in 1944 and the second on the banks of the great Irrawaddy along the infamous ‘Road to Mandalay’ in Burma in 1945.

Slim’s victories in 1944 and 1945 were profound, and yet were quickly forgotten by a Britain focused principally on the defeat of Germany, and by a United States gradually pushing back the barriers of Japanese militaristic imperialism in the Pacific. In late 1943 the 14th Army had begun to call itself the ‘Forgotten Army’, because of the apparent lack of interest back home of their exertions.

Sadly, from the time of the last climactic battles and the dash to seize Rangoon in May 1945 Slim’s achievements as the leader of this great army have equally been forgotten, although not of course by those who served under him who were all, as Mountbatten declared, ‘his devoted slaves’, nor indeed by their children and grandchildren who together make the Burma Star Association the only old soldiers’ association that actually continues to grow, rather than diminish.

What were these achievements? In terms of his contribution to Allied strategy in Burma and India between 1942 and 1945 they were threefold. First, he prevented, by his dogged command of the withdrawal from Burma the invasion of India proper in 1942 by a Japanese Army exulting in its omnipotence after the collapse of the rest of East Asia and the Pacific rim.

Second, he removed forever any further Japanese ambitions to invade India proper by his destruction of Mutaguchi’s legions in the Naga Hills around Kohima and the Manipur Plain around Imphal in the spring and early summer of 1944, and in so doing he decisively shattered the myth of Japanese invincibility that had for so long crippled the Allied cause.

Third, despite the prognostications of many, and subtly influencing Mountbatten to conform to his own strategy, Slim drove his armoured, foot and mule-borne and air-transported troops deep into Burma in late 1944 and 1945, across two of the world’s mightiest rivers, to outwit and outfight the 250,000 strong Burma Area Army of General Kimura and in so doing engineer the complete collapse of Japanese hegemony in Burma.

Given the pattern of British misfortune in 1942 and in 1943 it is not fanciful to argue that without Slim neither the safety of India (in 1942 as well as in 1944), nor the recovery of Burma in 1945, would ever have been possible. Slim’s leadership and drive came to dominate the 14 Army to such a degree that it became, in Jack Master’s phrase, ‘an extension of his own personality.’

Slim’s achievements need also to be examined from a more personal, professional perspective. That he was able to defend India’s eastern borders from imminent doom, and crush both Mutaguchi and Kimura in the gigantic and decisive struggles of 1944 and 1945 was due to his qualities as a military thinker and as a leader of men.

Slim was a master of intelligent soldiering. That a man becomes one of the most senior officer of his generation is not always evidence per se that he has mastered this most fundamental of requirements: in Slim’s case it was.

His approach to the building up of the fighting power of an army – from a situation of profound defeat and in the face of crippling resource constraints – is a model that deserves far greater attention today than it has received in the past. It was an approach built on the twin platforms of rigorous training and development of each individual’s will to win, through a deeply thought-out programme of support designed to meet the physical, intellectual and spiritual needs of each fighting man.

Slim’s description of General Sir George Giffard, his superior for a time, can equally be applied to himself: Giffard’s great strength, Slim commented, lay in his grasp of ‘the fundamentals of war – that soldiers must be trained before they can fight, fed before they can march, and relieved before they are worn out.’

Second, Slim was a remarkable coalition commander. The Army that defeated the might of the Japanese in both India and Burma during 1944 and 1945 was a thoroughly imperial one, seventy-five percent Indian, Gurkha and African. Even in the British Empire of the time it was not self-evident that a British officer would secure the commitment of the various diverse nationalities he commanded: indeed, many did not.

In his study of military command the psychiatrist Norman Dixon considered Slim’s quite obvious ability to join many of these diverse national groups to fight together in a single cause to be nothing less than remarkable, and the antithesis of the norm.

That he did so at a time of social and political unrest in India with the anti-colonial ‘Quit India’ campaign, and in the face of some early desertions to the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army under Subhas Chandra Bose, makes his achievements even the more remarkable. The British soldier was also suspicious of officers of the Indian Army, but Slim succeeded effortlessly in winning them over, too.

He ‘was the only Indian Army general of my acquaintance that ever got himself across to British troops’ recalled Fergusson. ‘Monosyllables do not usually carry a cadence; but to thousands of British troops, as well as to Indians and to his own beloved Gurkhas, there will always be a special magic in the words “Bill Slim.”

But in addition to his success in defeating the Japanese in 1944 and 1945, and in building up 14 Army to become a formidable fighting machine, Slim’s most abiding legacy was his approach to war, which at the time was singularly different to that adopted elsewhere during the war, either by Monty in Africa and North West Europe or Alexander in Italy.

Slim’s pre-eminent concern was to defeat the Japanese army facing him in Burma, not merely to recover territory, and he determined to do this through the complete dominance of the Japanese strategic plan. Training his troops relentlessly through monsoon, mountain and jungle, joining the command and operation of his land and air forces together, so that they served a single object, and delegating command to the lowest levels possible, Slim created an army of a power and fighting spirit rarely ever encountered in the history books.

In 1944 he allowed Mutaguchi’s 100,000 strong 15 Army to extend itself deep into India, there to be met by a ruthlessly determined 4 Corps, supplied by air and attacking at every opportunity the tenuous Japanese lines of communication back to the Chindwin. It was high risk, and more than one senior officer in Delhi and London despaired of success.

Slim, however, knew otherwise, and in the process of the climatic battles of Imphal and Kohima he succeeded in shattering the cohesion of a whole Japanese army and destroying its will to fight, a situation as yet unheard of for a fully formed Japanese army in the field. There were a number of close calls, and Slim was always the first to admit to his mistakes, but his steady nerve never failed. He moulded the Japanese offensive to suit his own plans, and step-by-step, he decisively broke it in the hills of eastern Assam and the Imphal plain.

Many commanders would then have sat on their laurels. Not so Slim. He was convinced that real victory against the Japanese required an aggressive pursuit, not just to the Chindwin but into the heart of Burma itself. Single-handedly he worked to put in place all the ingredients of a bold offensive to seize Mandalay at a time when every inclination in London and Washington was to seek an amphibious solution to the problem of Burma and thus avoid the entanglements of a land offensive.

Slim believed, however, that it could be done. Virtually alone he drove his plans forward, winning agreement and acceptance to his ideas as he went, particularly with Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Far East, and went on to execute in Burma in 1945 one of the most brilliant expositions of the strategic art that warfare has ever seen.

He did this in the face of difficulties of every sort and degree. Employing his abundant strategic initiative to the full, he succeeded in outwitting and destroying an even larger army under General Kimura along the Irrawaddy between Meiktila and Mandalay in the spring of 1945, Kimura himself describing Slim’s operation as the ‘masterstroke of allied strategy’. In both these operations Slim prefigured the doctrine of ‘manoeuvre warfare’.

Although Slim would not have recognised the term, his exercise of command in 14 Army indicates clearly that he espoused all of the fundamental characteristics. The modern British Army defines it as ‘the means of concentrating force to achieve surprise, psychological shock, physical momentum and moral dominance… At the operational level, manoeuvre involves more than just movement; it requires an attitude of mind which seeks to do nothing less than unhinge the entire basis of the enemy’s operational plan.’

It argues that the extreme military virtue does not lie, as Monty practised, in the direct confrontation of the enemy mass, in an attempt to erode his strength to the point where he no longer has the physical wherewithal to continue the contest, but rather in the subtlety of the “indirect approach”, where the enemy’s weaknesses rather than his strengths are exploited, and his mental strengths and, in particular his will to win are undermined without the necessity of a mass-on-mass confrontation of the type that characterised so much of Allied operations on both the Western and Eastern Fronts in Europe during the Second World War. Slim’s exercise of command in Burma makes him not merely a fine example of a ‘manoeuvrist’ commander but in actuality the template for modern manoeuvrist command.

‘Slim’s revitalisation of the Army had proved him to be a general of administrative genius’ argues the historian Duncan Anderson: ‘his conduct of the Burma retreat, the first and second Arakan, and Imphal-Kohima, had shown him to be a brilliant defensive general; and now, the Mandalay-Meiktila operation had placed him in the same class as Guderian, Manstein and Patton as an offensive commander.’

Mountbatten claimed that despite the reputation of others, such as the renowned self-publicist, Montgomery of Alamein, it was Slim who should rightly be regarded as the greatest British general of the Second World War. Slim’s failing was to deprecate any form of self-publicity believing, perhaps naively, that the sound of victory had a music all of its own. The ‘spin doctors’ of our own political generation have sadly taught us something Monty knew instinctively and exploited to his own advantage, namely that if you don’t blow your own trumpet no one else will.

The final word should be left to one who served under him. ‘“Bill” Slim was to us, averred Antony Brett-James, ‘a homely sort of general: on his jaw was carved the resolution of an army, in his stern eyes and tight mouth reside all the determination and unremitting courage of a great force.

His manner held much of the bulldog, gruff and to the point, believing in every one of us, and as proud of the “Forgotten Army” as we were. I believe that his name will descend into history as a badge of honour as great as that of the “Old Contemptibles.” Sadly, Slim’s name and achievements have not done what Brett-James hoped, and it is now the responsibility of a new generation to understand and appreciate his achievements.’

Robert Lyman’s A War of Empires will be published by Osprey in November 2021.

————————————————————————————–Lord William Slim in the House of Lords London UK