From the Feral Irishman: “The Magic Carpet Ride”

Returning the troops home after WWII was a daunting task

The Magic Carpet that flew everyone home.

The U.S. military experienced an unimaginable increase during World War II.

In 1939, there were 334,000 servicemen, not counting the Coast Guard.

In 1945, there were over 12 million, including the Coast Guard.

At the end of the war, over 8 million of these men and women were scattered overseas in Europe, the Pacific and Asia. Shipping them out wasn’t a particular problem but getting them home was a massive logistical headache.

The problem didn’t come as a surprise, as Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had already established committees to address the issue in 1943.

Soldiers returning home on the USS General Harry Taylor in August 1945

When Germany fell in May 1945, the U.S. Navy was still busy fighting in the

Pacific and couldn’t assist.

The job of transporting 3 million men home fell to the Army and the Merchant Marine.

300 Victory and Liberty cargo ships were converted to troop transports for the task.

During the war, 148,000 troops crossed the Atlantic west to east each month;

the rush home ramped this up to 435,000 a month over 14 months.

Hammocks crammed into available spaces aboard the USS Intrepid

In October 1945, with the war in Asia also over, the Navy started chipping in,

converting all available vessels to transport duty.

On smaller ships like destroyers, capable of carrying perhaps 300 men,

soldiers were told to hang their hammocks in whatever nook and cranny they could find.

Carriers were particularly useful, as their large open hangar decks could house 3,000

or more troops in relative comfort, with bunks, sometimes in stacks of five welded

or bolted in place.

Bunks aboard the Army transport SS Pennant

The Navy wasn’t picky, though: cruisers, battleships, hospital ships,

even LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) were packed full of men yearning for home.

Two British ocean liners under American control, the RMS Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth,

had already served as troop transports before and continued to do so during the operation,

each capable of carrying up to 15,000 people at a time, though their normal,

peacetime capacity was less than 2,200.

Twenty-nine ships were dedicated to transporting war brides:

women married to American soldiers during the war.

Troops performing a lifeboat drill onboard the Queen Mary in December 1944,

before Operation Magic Carpet

The Japanese surrender in August 1945 came none too soon,

but it put an extra burden on Operation Magic Carpet.

The war in Asia had been expected to go well into 1946 and the Navy and

the War Shipping Administration were hard-pressed to bring home all

the soldiers who now had to get home earlier than anticipated.

The transports carrying them also had to collect numerous POWs

from recently liberated Japanese camps, many of whom suffered

from malnutrition and illness

U.S. soldiers recently liberated from Japanese POW camps

The time to get home depended a lot on the circumstances. USS Lake Champlain,

a brand new Essex-class carrier that arrived too late for the war,

could cross the Atlantic and take 3,300 troops home a little under 4 days and 8 hours.

Meanwhile, troops going home from Australia or India would sometimes spend

months on slower vessels.

Hangar of the USS Wasp during the operation

There was enormous pressure on the operation to bring home as many men

as possible by Christmas 1945

Therefore, a sub-operation, Operation Santa Claus, was dedicated to the purpose.

Due to storms at sea and an overabundance of soldiers eligible for return home,

however, Santa Claus could only return a fraction in time and still not quite home

but at least to American soil.

The nation’s transportation network was overloaded:

trains heading west from the East Coast were on average 6 hours behind schedule

and trains heading east from the West Coast were twice that late.

The crowded flight deck of the USS Saratoga.

The USS Saratoga transported home a total of 29,204 servicemen during Operation Magic Carpet,

more than any other ship.

Many freshly discharged men found themselves stuck in separation centers

but faced an outpouring of love and friendliness from the locals.

Many townsfolk took in freshly arrived troops and invited them to Christmas dinner

in their homes.

Still others gave their train tickets to soldiers and still others organized quick parties

at local train stations for men on layover.

A Los Angeles taxi driver took six soldiers all the way to Chicago;

another took another carload of men to Manhattan, the Bronx, Pittsburgh,

Long Island, Buffalo and New Hampshire.

Neither of the drivers accepted a fare beyond the cost of gas.

Overjoyed troops returning home on the battleship USS Texas

All in all, though, the Christmas deadline proved untenable.

The last 29 troop transports, carrying some 200,000 men from the

China-India-Burma theater, arrived to America in April 1946,

bringing Operation Magic Carpet to an end,

though an additional 127,000 soldiers still took until September

to return home and finally lay down the burden of war.

Category: Interesting stuff

My Gentle Readers, Frankly this has been one of my better DVD buys lately. In that it was so refreshing to go back to a time.

When the Land abounded in adults and even during a horrible Civil War. They were some giants walking the land & because of their guidance. Made us the Last Great Hope of Man.

‘I’ll Never Be the Same’: My Ukrainian Wife’s First Trip to the United States

For Lilya Peterson—shown here in Boca Grande, Florida—visiting the United States was a lifelong dream. “This is the greatest country in the world,” she said. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

By the size of its economy, or the strength of its military?

By the height of its city skylines, or the audacity of the moon landings?

Perhaps, by the heroism of the Marines who landed on Iwo Jima, or of the Army soldiers who landed on Omaha Beach?

Maybe. But America’s greatness is not always measured like in the movies or a campaign speech. Sometimes, an anonymous act of gratitude is proof enough, even if we, as Americans, don’t always see it that way.

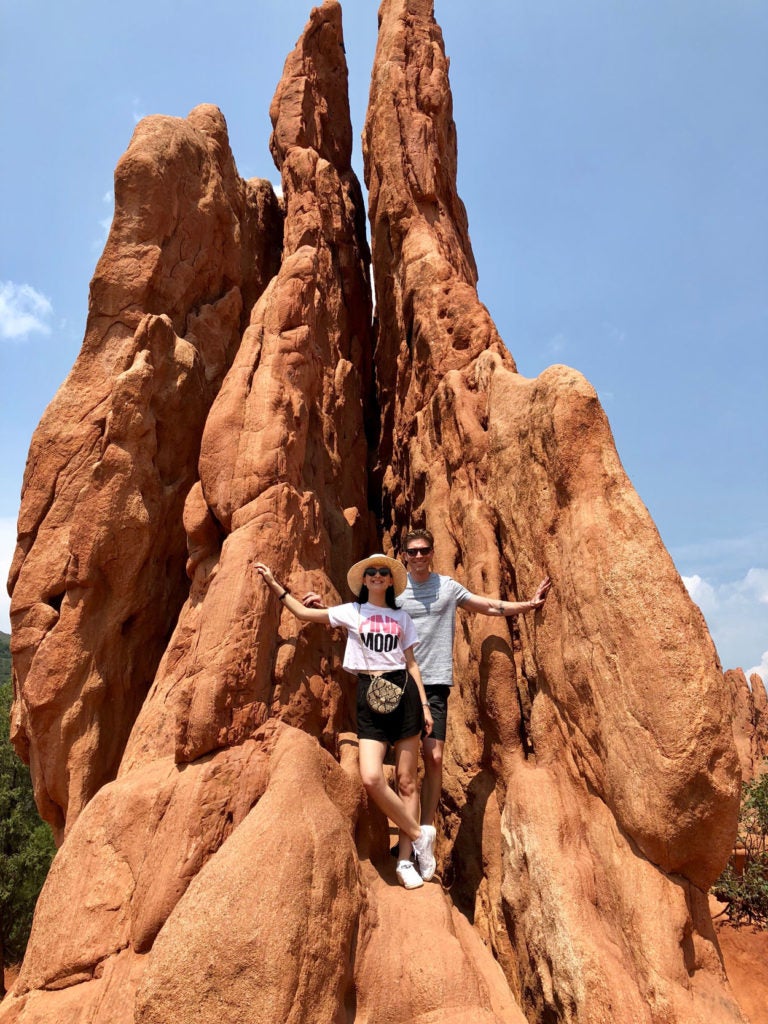

At Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs, Colorado. For one month, the author and his wife, Lilya, traveled across the United States for their honeymoon. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

In August, my wife, Lilya, and I were at dinner in Geyserville, California, with my younger brother, Drew, and his girlfriend, Gabrielle.

We’d been wine tasting all afternoon and had rounded off the day with a few cocktails to boot. Feeling a bit loosened up, my brother and I, as is our habit, slipped into a familiar topic of conversation—the war in Afghanistan.

You see, both Drew and I are U.S. military veterans. And, naturally, we get to talking about our wartime experiences whenever we’re together. Often a bit too loudly, as Lilya and Gabrielle gently suggested on that night in Geyserville.

In any case, as we wrapped up dinner and asked for the check, the waitress informed us that someone had already paid our bill. We asked who this person was, but he or she had already left, the waitress explained.

“They asked me to tell you, ‘Thank you for your service,’” she said.

My brother and I were speechless. It is, after all, all too easy to assume the country has moved on and forgotten about our wars when so many of the things that divide us seem to occupy so much of the news.

The United States is an inspiration for many people fighting for their freedom around the world, such as these Kurdish peshmerga soldiers outside Mosul, Iraq, in 2016. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

On the walk back to the hotel that night, my wife, who is Ukrainian, told me, “I’m so shocked and impressed. I’ve never seen such a kind gesture by a stranger. It was magnificent.”

I was moved by the gesture, too. But it wasn’t the first time someone in America had bought me a drink for being a veteran. What I didn’t immediately understand is that from my wife’s point of view, it was a singularly unprecedented, characteristically American, display of gratitude.

A week later, Lilya and I were having a drink at a bar in my hometown of Sarasota, Florida. We chatted with the barman and it came up that I was a former Air Force pilot and a war correspondent.

When it was time to square up the tab, the barman said with a smile that he wouldn’t take my money.

“Thank you for your service,” he simply explained.

On our way out the door, my wife stopped, took my hand, turned to me, and said, “This is the greatest country in the world.”

Love and War

In the summer of 2014, I left for Ukraine to report on the war, thinking I’d be gone for only two weeks. More than four years later, the war isn’t over and I still live in Ukraine. Most importantly, I’m now married to Lilya.

In August, Lilya and I traveled across the United States on our honeymoon. It was her first trip to America. For my part, I’d spent only a handful of weeks in the U.S. since I first left for Ukraine in 2014. So, this trip was a homecoming of sorts for me, as well as a chance to take stock of how much America had changed in the years I’ve been away.

You, dear reader, surely understand all the challenges facing our country. You’re likely bombarded with reminders of these challenges each time you go online or turn on your TV.

Yet, I want to share with you a perspective of your country that might be as foreign to you as the conflicts on which I’ve reported. It’s the perspective of my wife—a 22-year-old Ukrainian woman who was born in the shadow of the Soviet Union and spent most of her young life amid the backdrop of revolutions and war.

Despite all the broken dreams in her country, Lilya, like so many Ukrainians of her generation, possesses a clear vision of the life she wants and deserves. And you, dear reader, are already living it.

When the jet broke through the clouds and out the window we saw the lights of the New York City skyline, Lilya smiled and said, “This is the dream of all my life.”

Checkpoints

We started in New York City. Despite my best efforts not to, I wept at ground zero, remembering things from my youth I don’t often revisit. Like watching on TV as the towers fell during a morning class at the Air Force Academy. I was only 19, but I understood what that day meant for my future.

The author and his wife, Lilya, in the Cadet Chapel at the U.S. Air Force Academy. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

We marveled at the skyscrapers in New York and Chicago, and we visited all of Washington, D.C.’s monuments. Later, under the shadow of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, we visited the Air Force Academy, my alma mater.

I won’t lie, I bursted with pride to show Lilya that place.

We walked across the terrazzo—the academy’s massive central courtyard—and Lilya shook her head in disbelief at the spectacle of the freshmen (known as doolies) who ran along the marble strips, dutifully stopping to recite volumes of memorized knowledge at the upper class cadets’ behests.

At the academy’s War Memorial—a black stone monument to graduates who fell in battle—I took a quiet moment alone and ran my fingers across the freshly engraved names of remembered faces.

During our visit, I was honored with the opportunity to speak to a couple classes, as well as with the faculty, to share my wartime experiences. During one classroom session, the professor put Lilya on the spot and asked for her impression of America.

Impromptu public speaking in a foreign language isn’t easy. But she nailed it.

Without missing a beat, Lilya replied: “This is the greatest country in the world. But most Americans don’t know it.”

Gratitude

From Colorado we flew to Phoenix and drove across the desert to the Grand Canyon and then on to Las Vegas. In California, we visited Hollywood, drove over the Golden Gate Bridge, hiked in the redwood forests, and enjoyed wine country to its fullest. We doubled back across the country to Florida and toured the Kennedy Space Center, where we saw the Space Shuttle Atlantis and a Saturn V moon rocket.

In the end, we traveled from sea to shining sea and concluded our journey in Sarasota, where Lilya met my 93-year-old grandmother, Joan, for the first time.

Lilya with her grandmother-in-law, Joan Peterson, in Sarasota, Florida. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

As they held hands and chatted, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude that we were able to find a way to America while there was still time. And while more than 70 years separated their lives, I also observed a special bond between my wife and grandmother.

They both possess a unique appreciation for life’s little pleasures. And for good reason. My grandmother has lived through the Great Depression, wars, and societal upheavals. For her part, my young wife has already lived through two revolutions and a war.

Of course, you don’t have to endure such historic challenges to appreciate life’s blessings. But, I must say, it’s all too easy to misjudge the gravity of life’s problems when you’re used to peace and prosperity—after all, there’s no microaggression, no trigger, no slur or verbal insult that could ever compare with the impartial brutalities of revolution and war.

The author with his grandmother, Joan Peterson, in Sarasota, Florida. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

The truth is, every American, each and every one of us, is privileged. We’re privileged because we are American.

If you don’t think so then lift your eyes to the horizon, over which exists a world where the overwhelming majority of humanity does not enjoy the self-evident entitlements we so flippantly take for granted—things like life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The more cynical among us will likely roll their eyes at the preceding sentence, writing it off as overwrought jingoism. But when hardship and war comprise your daily reality, you don’t take America’s greatness lightly, or for granted.

Whether we want it or not, we Americans have inherited an awesome responsibility. We are the caretakers of the promise of democracy for people around the world who yearn for it.

Of course, we’re not the only democracy in the world. But I’ve seen firsthand how the ideal of American democracy stands alone in the eyes of Ukraine’s soldiers, the Kurds in Iraq, or even octogenarian Tibetan freedom fighters. For them, America symbolizes a dream worth fighting for.

I was proudest of my homeland when I showed it to my wife for the first time and saw her eyes illuminate in witness of a dream foretold. I also silently hoped that America wouldn’t let her down.

The author and his wife at dinner at the top of the John Hancock Center in Chicago. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

Yes, we may fail in our time to realize the promise of our founding for every American.

Yet, despite the long shadow of our past sins and the gravity of our contemporary shortcomings, we haven’t quit yet and better make sure we never do.

Because the world is always watching us. Always. And there are plenty of dark forces in this world held at bay by the simple fact that America is still a dream worth fighting for.

Yes, we aren’t perfect. But if not us then who?

Common Bonds

The front lines against tyranny aren’t always found on the battlefields against goose-stepping armies. Sometimes, that battle is won at the dinner table, in a classroom, in a random encounter on the sidewalk, or even in a Facebook post.

Sometimes, victory is measured by the courage to show decency and respect and to find common purpose with someone with whom you share nothing in common except for being American.

After everything I’ve seen, I still believe that if the better angels of our nature win in America, then they will win everywhere. The world is watching us, remember.

In Las Vegas, Nevada—one stop on a monthlong, cross-country trip for the author and his wife, Lilya. After more than four years of reporting on the war in Ukraine, it was a homecoming of sorts for the author. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

So, how do you measure America’s greatness?

My wife saw our moon rockets and our skyscrapers and our monuments and our natural wonders. Yet, in the end, what impressed her most were those unnecessary and unsolicited acts of thanksgiving for my military service by total strangers.

“I never thought that random people would be so kind to strangers just because they respect them,” Lilya told me. “America really is the greatest country on earth.”

She paused for a beat and then added, “This trip changed the way I see everything, and I’ll never be the same.”

I shamelessly clipped this one from a friend on the book of Face

The passenger steamer SS Warrimoo was quietly knifing its way through the waters of the mid-Pacific on its way from Vancouver to Australia. The navigator had just finished working out a star fix and brought Captain John DS. Phillips, the result.

The Warrimoo’s position was LAT 0º 31′ N and LONG 179 30′ W. The date was 31 December 1899. “Know what this means?” First Mate Payton broke in, “We’re only a few miles from the intersection of the Equator and the International Date Line”.

Captain Phillips was prankish enough to take full advantage of the opportunity for achieving the navigational freak of a lifetime. He called his navigators to the bridge to check & double check the ship’s position.

He changed course slightly so as to bear directly on his mark. Then he adjusted the engine speed. The calm weather & clear night worked in his favor.

At mid-night the SS Warrimoo lay on the Equator at exactly the point where it crossed the International Date Line! The consequences of this bizarre position were many:

The forward part (bow) of the ship was in the Southern Hemisphere & in the middle of summer.

In the bow (forward) part it was 1 January 1900.

I bet that is not a cheap hunt! Grumpy

The Man Who Saved Korea

Matthew B. Ridgway, who brought a beaten Eighth Army back from disaster in 1951, was a thinking—and fighting—man’s soldier.

IF YOU ASKED A GROUP OF AVERAGE AMERICANS to name the greatest American general of the twentieth century, most would nominate Dwight Eisenhower, the master politician who organized the Allied invasion of Europe, or Douglas MacArthur, a leader in both world wars, or George C. Marshall, the architect of victory in World War II. John J.

Pershing and George S. Patton would also get a fair number of votes. But if you ask professional soldiers that question, a surprising number of them will reply: “Ridgeway.”

When they pass this judgment, they are not thinking of the general who excelled as a division commander and an army corps commander in World War II.

Many other men distinguished themselves in those roles. The soldiers are remembering the general who rallied a beaten Eighth Army from the brink of defeat in Korea in 1951.

THE SON OF A WEST POINTER who retired as a colonel of the artillery, Matthew Bunker Ridgeway graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1917.

Even there, although his scholastic record was mediocre, he was thinking about how to become a general. One trait he decided to cultivate was an ability to remember names. By his first-class year, he was able to identify the entire 750-man student body.

To his dismay, instead of being sent into combat in France, Ridgeway was ordered to teach Spanish at West Point, an assignment that he was certain meant the death knell of his military career.

(As it turned out, it was probably the first of many examples of Ridgway luck; like Eisenhower and Omar Bradley, he escaped the trench mentality that World War I experience inflicted on too many officers.)

Typically, he mastered the language, becoming one of a handful of officers who were fluent in the second tongue of the western hemisphere.

He stayed at West Point for six years in the course of which he became acquainted with its controversial young superintendent, Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, who was trying in vain to stop the academy from still preparing for the War of 1812.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Ridgeway’s skills as a writer and linguist brought him more staff assignments than he professed to want—troop leadership was the experience that counted on the promotion ladder.

But Ridgeway’s passion for excellence and commitment to the army attracted the attention of a number of people, notably that of a rising star in the generation ahead of him, George Marshall. Ridgeway served under Marshall in the 15th Infantry in China in the mid-1930s and was on his general staff in Washington when Pearl Harbor plunged the nation into World War II.

As the army expanded geometrically in the next year, Ridgeway acquired two stars and the command of the 82nd Division.

When Marshall decided to turn it into an airborne outfit, Ridgeway strapped on a parachute and jumped out of a plane for the first time in his life. Returning to his division, he cheerfully reported there was nothing to the transition to paratrooper.

He quieted a lot of apprehension in the division—although he privately admitted to a few friends that “nothing” was like jumping off the top of a moving freight train onto a hard roadbed.

Dropped into Sicily during the night of July 9, 1943, Ridgeway’s paratroopers survived a series of snafus. Navy gunners shot down twenty of their planes as they came over the Mediterranean from North Africa.

In the darkness their confused pilots scattered them all over the island. Nevertheless, they rescued the invasion by preventing the crack Hermann Göring panzer division from attacking the fragile beachhead and throwing the first invaders of Hitler’s Fortress Europe into the sea.

In this campaign, Ridgeway displayed many traits that became hallmarks of his generalship. He scored a rear-area command post.

Battalion and even company commanders never knew when they would find Ridgeway at their elbows, urging them forward, demanding to know why they were doing this and not that.

His close calls with small- and large-caliber enemy fire swiftly acquired legendary proportions. Even Patton, who was not shy about moving forward, ordered Ridgeway to stop trying to be the 82nd Division’s point man. Ridgeway pretty much ignored the order, calling it “a compliment.”

FROM PATTON, RIDGEWAY ACQUIRED ANOTHER COMMAND HABIT: the practice of stopping to tell lower ranks—military policemen, engineers building bridges—they were doing a good job. He noted the remarkable way this could energize an entire battalion, even a regiment.

At the same time, Ridgeway displayed a ruthless readiness to relieve any officer who did not meet his extremely high standards of battlefield performance. Celerity and aggressiveness were what he wanted. If an enemy force appeared on a unit’s front, he wanted an immediate deployment for flank attacks. He did not tolerate commanders who sat down and thought things over for an hour or two.

In the heat of battle, Ridgeway also revealed an unrivaled capacity to taunt the enemy. One of his favorite stunts was to stand in the middle of a road under heavy artillery fire and urinate to demonstrate his contempt for German accuracy. Aides and fellow generals repeatedly begged him to abandon this bravado. He ignored them.

Ridgeway’s experience as an airborne commander spurred the evolution of another trait that made him almost unique among American soldiers—a readiness to question, even to challenge, the policies of his superiors.

After the snafus of the Sicily drop, Eisenhower and other generals concluded that division-size airborne operations were impractical. Ridgeway fought ferociously to maintain the integrity of his division.

Winning that argument, he found himself paradoxically menaced by the widespread conclusion that airborne assault could solve problems with miraculous ease.

General Harold Alexander, the British commander of the Allied invasion of Italy, decided Ridgeway’s paratroopers were a God-given instrument for disrupting German defense plans. Alexander ordered the 82nd Airborne to jump north of Rome, seize the city, and hold it while the main army drove from their Salerno beachhead to link up with them.

Ridgeway was appalled. His men would have to fly without escort—Rome was beyond the range of Allied fighters—risking annihilation before they got to the target.

There were at least six elite German divisions near the city, ready and willing to maul the relatively small 82nd Airborne. An airborne division at this point in the war had only 8,000 men.

Their heaviest gun was a 75 pack howitzer, “a peashooter,” in Ridgeway’s words, against tanks. For food, ammunition, fuel, transportation, the Americans were depending on the Italians, who were planning to double-cross the Germans and abandon the war.

Ridgeway wangled an interview with General Alexander, who listened to his doubts and airily dismissed them. “Don’t give this another thought, Ridgeway. Contact will be made with your division in three days—five at the most,” he said.

RIDGEWAY WAS IN A QUANDARY. He could not disobey the direct orders of his superior without destroying his career. He told his division to get ready for the drop, but he refused to abandon his opposition, even though the plan had the enthusiastic backing of Dwight Eisenhower, who was conducting negotiations with the Italians from his headquarters in Algiers.

Eisenhower saw the paratroopers as a guarantee that the Americans could protect the Italians from German retribution.

Ridgeway discussed the dilemma with Brigadier General Maxwell Taylor, his artillery officer, who volunteered to go to Rome incognito and confer with the Italians on the ground.

Ridgeway took this offer to General Walter Bedell Smith, Alexander’s American chief of staff, along with more strenuous arguments against the operation.

Smith persuaded Alexander to approve Taylor’s mission. Taylor and an air corps officer traveled to Rome disguised as captured airrmen and met Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the acting prime minister, who was in charge of the negotiations.

Meanwhile, plans for the drop proceeded at a dozen airfields in Sicily. If Taylor found the Italians unable to keep their promises of support, he was to send a radio message with the code word innocuous in it.

In Rome, Taylor met Badoglio and was appalled by what he heard. The Germans were wise to the Italians’ scheme and had reinforced their divisions around Rome.

The 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division alone now had 24,000 men and 200 tanks—enough firepower to annihilate the 82nd Airborne twice over.

A frantic Taylor sent three separate messages over different channels to stop the operation, but word did not reach the 82nd until sixty-two planes loaded with paratroopers were on the runways warming their engines. Ridgeway sat down with his chief of staff, shared a bottle of whiskey, and wept with relief.

Looking back years later, Ridgeway declared that when the time came for him to meet his maker, his greatest source of pride would not be his accomplishments in battle but his decision to oppose the Rome drop. He also liked to point out that it took seven months for the Allied army to reach the Eternal City.

Repeatedly risking his career in this unprecedented fashion, Ridgeway was trying to forge a different kind of battle leadership. He had studied the appalling slaughters of World War I and was determined that they should never happen again.

He believed “the same dignity attaches to the mission given a single soldier as to the duties of the commanding general. . . . All lives are equal on the battlefield, and a dead rifleman is as great a loss in the sight of God as a dead general.”

IN THE NORMANDY INVASION, RIDGEWAY HAD NO DIFFICULTY accepting the 82nd’s task.

Once more, his men had to surmount a mismanaged airdrop in which paratroopers drowned at sea and in swamps and lost 60 percent of their equipment. Ridgeway found himself alone in a pitch-dark field. He consoled himself with the thought that “at least if no friends were visible, neither were any foes.”

Ten miles away, his second-in-command, James Gavin, took charge of most of the fighting for the next twenty-four hours.

The paratroopers captured only one of their assigned objectives, but it was a crucial one, the town of Sainte-Mére-Eglise, which blocked German armor from attacking Utah beach. Ridgway was given a third star and command of the XVIII Airborne Corps.

By this time he inspired passionate loyalty in the men around him. Often it came out in odd ways. One day he was visiting a wounded staff officer in an aid station. A paratrooper on the stretcher next to him said, “Still sticking your neck out, huh, General?” Ridgeway never forgot the remark.

For him it represented the affection one combat soldier feels for another.

Less well known than his D-Day accomplishments was Ridgeway’s role in the Battle of the Bulge.

When the Germans smashed into the Ardennes in late December 1944, routing American divisions along a 75-mile front, Ridgeway’s airborne corps again became a fire brigade. The “battling bastards of Bastogne”—the 101st Airborne led by Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe—got most of the publicity for foiling the German lunge toward Antwerp.

But many historians credit Ridgeway’s defense of the key road junction of Saint-Vith as a far more significant contribution to the victory.

Ridgeway acquired a visual trademark, a hand grenade attached to his paratrooper’s shoulder harness on one side and a first-aid kit, often mistaken for another grenade, on the other strap.

He insisted both were for practical use, not for picturesque effect like Patton’s pearl-handled pistols. In his jeep he also carried an old .30-06 Springfield rifle, loaded with armor-piercing cartridges.

On foot one day deep in the Ardennes forest, trying to find a battalion CP, he was carrying the gun when he heard a “tremendous clatter.” Through the trees he saw what looked like a light tank with a large swastika on its side.

He fired five quick shots at the Nazi symbol and crawled away on his belly through the snow. The vehicle turned out to be a self-propelled gun. Inside it, paratroopers who responded to the shots found five dead Germans.

THIS WAS THE MAN—now at the Pentagon, as deputy chief of staff for administration and training—whom the army chose to rescue the situation in Korea when the Chinese swarmed over the Yalu River in early December 1950 and sent EUSAK (the Eighth U.S. Army in Korea) reeling in headlong retreat.

Capping the disarray was the death of the field commander, stumpy Major General Walton (“Johnnie”) Walker, in a jeep accident. Ridgeway’s first stop was Tokyo, where he was briefed by the supreme commander, Douglas MacArthur.

After listening to a pessimistic summary of the situation, Ridgeway asked: “General, if I get over there and find the situation warrants it, do I have your permission to attack?”

“The Eighth Army is yours, Matt,” MacArthur responded. “Do what you think best.”

MacArthur was giving Ridgeway freedom—and responsibility—he had never given Walker. The reason was soon obvious: MacArthur was trying to distance himself from a looming disaster.

Morale in the Eighth Army had deteriorated alarmingly while they retreated before the oncoming Chinese. “Bugout fever” was endemic. Within hours of arriving to take command, Ridgeway abandoned his hopes for an immediate offensive. His first job was to restore this beaten army’s will to fight.

He went at it with incredible verve and energy. Strapping on his parachute harness with its hand grenade and first-aid kit, he toured the front for three days in an open jeep in bitter cold. “I held to the old-fashioned idea that it helped the spirits of the men to see the Old Man up there in the snow and sleet . . . sharing the same cold miserable existence they had to endure,” he said.

But Ridgeway admitted that until a kindhearted major dug up a pile-lined cap and warm gloves for him, he “damn near froze.

Everywhere he went, Ridgeway exercised his fabulous memory for faces. By this time he could recognize an estimated 5,000 men at a glance. He dazzled old sergeants and MPs on lonely roads by remembering not only their names but where they had met and what they had said to each other.

But this trick was not enough to revive EUSAK. Everywhere Ridgeway found the men unresponsive, reluctant to answer his questions, even to air their gripes.

The defeatism ran from privates through sergeants all the way up to the generals. He was particularly appalled by the atmosphere in the Eighth Army’s main command post in Taegu. There they were talking about withdrawing from Korea, frantically planning how to avoid a Dunkirk.

In his first 48 hours, Ridgeway had met with all his American corps and division commanders and all but one of the Republic of Korea division commanders.

He told them—as he had told the staffers in Taegu—that he had no plans whatsoever to evacuate Korea. He reiterated what he had told South Korean president Syngman Rhee in their meeting: “I’ve come to stay. ”

But words could not restore the nerve of many top commanders. Ridgeway’s reaction to this defeatism was drastic: He cabled the Pentagon that he wanted to relieve almost every division commander and artillery commander in EUSAK.

He also supplied his bosses with a list of younger fighting generals he wanted to replace the losers. This demand caused political palpitations in Washington, where MacArthur’s growing quarrel with President Harry Truman’s policy was becoming a nightmare.

Ridgeway eventually got rid of his losers—but not with one ferocious sweep. The ineffective generals were sent home singly over the next few months as part of a “rotation policy.”

Meanwhile, in a perhaps calculated bit of shock treatment, Ridgeway visited I Corps and asked the G-3 to brief him on their battle plans. The officer described plans to withdraw to “successive positions.”

“What are your attack plans?” Ridgeway growled. The officer floundered. “Sir—we are withdrawing.” There were no attack plans. “Colonel, you are relieved,” Ridgeway said.

That is how the Eighth Army heard the story. Actually, Ridgeway ordered the G-3’s commanding officer to relieve him—which probably intensified the shock effect on the corps.

Many officers felt, perhaps with some justice, that Ridgeway was brutally unfair to the G-3, who was only carrying out the corps commander’s orders. But Ridgeway obviously felt the crisis justified brutality.

As for the lower ranks, Ridgeway took immediate steps to satisfy some of their gripes. Warmer clothing was urgently demanded from the States.

Stationery to write letters home, and to wounded buddies, was shipped to the front lines—and steak and chicken were added to the menu, with a ferocious insistence that meals be served hot.

Regimental, division, and corps commanders were told in language Ridgeway admitted was “often impolite” that it was time to abandon creature comforts and slough off their timidity about getting off the roads and into the hills, where the enemy was holding the high ground.

Again and again Ridgeway repeated the ancient army slogan “Find them! Fix them! Fight them! Finish them!”

As he shuttled across the front in a light plane or a helicopter, Ridgeway studied the terrain beneath him. He was convinced a massive Communist offense was imminent. He not only wanted to contain it, he wanted to inflict maximum punishment on the enemy.

He knew that for the time being he would have to give some ground, but he wanted the price to be high. South of the Han River, he assigned Brigadier General Garrison Davidson, a talented engineer, to take charge of several thousand Korean laborers and create a “deep defensive zone” with a trench system, barbed wire, and artillery positions.

RIDGEWAY ALSO PREACHED DEFENSE IN DEPTH to his division and regimental commanders in the lines they were holding north of the Han.

Although they lacked the manpower to halt the Chinese night attacks, he said that by buttoning up tight, unit by unit, at night and counterattacking strongly with armor and infantry teams during the day, the U.N. army could inflict severe punishment on anyone who had come through the gaps in their line.

At the same time, Ridgeway ordered that no unit be abandoned if cut off. It was to be “fought for” and rescued unless a “major commander” after “personal appraisal” Ridgeway-style—from the front lines—decided its relief would cost as many or more men.

Finally, in this race against the looming Chinese offensive, Ridgeway tried to fill another void in the spirit of his men. He knew they were asking each other, “What the hell are we doing here in this God-forgotten spot?” One night he sat down at his desk in his room in Seoul and tried to answer that question.

His first reasons were soldierly: They had orders to fight from the president of the United States, and they were defending the freedom of South Korea.

But the real issues were deeper—”whether the power of Western civilization, as God has permitted it to flower in our own beloved lands, shall defy and defeat Communism; whether the rule of men who shoot their prisoners, enslave their citizens and deride the dignity of man, shall displace the rule of those to whom the individual and his individual rights are sacred.”

In that context, Ridgeway wrote, “the sacrifices we have made, and those we shall yet support, are not offered vicariously for others but in our own direct defense.”

On New Year’s Eve, the Chinese and North Koreans attacked with all-out fury. The Eighth Army, Ridgeway wrote, “were killing them by the thousands,” but they kept coming.

They smashed huge holes in the center of Ridgeway’s battle line, where ROK divisions broke and ran. Ridgeway was not surprised—having met their generals, he knew most had little more than a company commander’s experience or expertise. Few armies in existence had taken a worse beating than the ROKs in the first six months of the war.

By January 2 it was evident that the Eighth Arrny would have to move south of the Han River and abandon Seoul. As he left his headquarters, Ridgeway pulled from his musette bag a pair of striped flannel pajama pants “split beyond repair in the upper posterior region.” He tacked them to the wall, the worn-out seat flapping. Above them, in block letters, he left a message:

TO THE COMMANDING GENERAL

CHINESE COMMUNIST FORCES

WITH THE COMPLIMENTS OF

THE COMMANDING GENERAL

EIGHTH ARMY

The story swept through the ranks with predictable effect.

The Eighth Army fell back fifteen miles south of the Han to the defensive line prepared by General Davidson and his Korean laborers. They retreated, in Ridgeway’s words, “as a fighting army, not as a running mob.”

They brought with them all their equipment and, most important, their pride. They settled into the elaborate defenses and waited for the Chinese to try again.

The battered Communists chose to regroup. Ridgeway decided it was time to come off the floor with some Sunday punches of his own.

He set up his advanced command post on a bare bluff at Yoju, about one-third of the way across the peninsula, equidistant from the I Corps and X Corps headquarters.

For the first few weeks, he operated with possibly the smallest staff of any American commander of a major army.

Although EUSAK’s force of 350,000 men was in fact the largest field army ever led by an American general, Ridgeway’s staff consisted of just six people: two aides, one orderly, a driver for his jeep, and a driver and radio operator for the radio jeep that followed him everywhere.

He lived in two tents, placed end-to-end to create a sort of two-room apartment and heated by a small gasoline stove. Isolated from the social and military formalities of the main CP at Taegu, Ridgeway had time for “uninterrupted concentration” on his counteroffensive.

Nearby was a crudely leveled airstrip from which he took off repeatedly to study the terrain in front of him. He combined this personal reconnaissance with intensive study of relief maps provided by the Army Map priceless asset.”

Soon his incredible memory had absorbed the terrain of the entire front, and “every road, every cart track, every hill, every stream, every ridge in that area . . we hoped to control . . . became as familiar to me as . my own backyard,” he later wrote. When he ordered an advance into a sector, he knew exactly what it might involve for his infantrymen.

ON JANUARY 25, WITH A THUNDEROUS ERUPTION OF MASSED ARTILLERY, the Eighth Army went over to the attack in Operation Thunderbolt.

The goal was the Han River, which would make the enemy’s grip on Seoul untenable. The offensive was a series of carefully planned advances to designated “phase lines,” beyond each of which no one advanced until every assigned unit reached it.

Again and again Ridgeway stressed the importance of having good coordination, inflicting maximum punishment, and keeping major units intact. He called it “good footwork combined with firepower.” The men in the lines called it “the meat grinder.”

To jaundiced observers in the press, the army’s performance was miraculous. Rene Cutforth of the BBC wrote: “Exactly how and why the new army was transformed…from a mob of dispirited boobs…to a tough resilient force is still a matter for speculation and debate.”

A Time correspondent came closest to explaining it: “The boys aren’t up there fighting for democracy now. They’re fighting because the platoon leader is leading them and the platoon leader is fighting because of the command, and so on right up to the top.”

By February 10 the Eighth Army had its left flank anchored on the Han and had captured Inchon and Seoul’s Kimpo Airfield. After fighting off a ferocious Chinese counterattack on Lincoln’s birthday, Ridgeway launched offensives from his center and right flank with equal success.

In one of these, paratroopers were used to trap a large number of Chinese between them and an armored column. Ridgeway was sorely tempted to jump with them, but he realized it would be “a damn fool thing” for an army commander to do. Instead, he landed on a road in his light plane about a half hour after the paratroopers hit the ground.

M-1s were barking all around him. At one point a dead Chinese came rolling down a hill and dangled from a bank above Ridgeway’s head.

His pilot, an ex-infantryman, grabbed a carbine out of the plane and joined the shooting. Ridgeway stood in the road, feeling “that lifting of the spirits, that sudden quickening of the breath and the sudden sharpening of all the senses that comes to a man in the midst of battle.”

None of his exploits in Korea better demonstrates why he was able to communicate a fierce appetite for combat to his men.

Still another incident dramatized Ridgeway’s instinctive sympathy for the lowliest private in his ranks.

In early March he was on a hillside watching a battalion of the 1st Marine Division moving up for an attack. In the line was a gaunt boy with a heavy radio on his back. He kept stumbling over an untied shoelace. “Hey, how about one of you sonsabitches tying my shoe?” he howled to his buddies. Ridgeway slid down the snowy bank, landed at his feet, and tied the laces.

Fifty-four days after Ridgeway took command, the Eighth Army had driven the Communists across the 38th parallel, the line dividing North and South Korea, inflicting enormous losses with every mile they advanced.

The reeling enemy began surrendering by the hundreds. Seoul was recaptured on March 14, a symbolic defeat of tremendous proportions to the Communists’ political ambitions.

Ridgeway was now “supremely confident” his men could take “any objective” assigned to them. “The American flag never flew over a prouder, tougher, more spirited and more competent fighting force than was the Eighth Army as it drove north beyond the parallel,” he declared.

But he agreed with President Truman’s decision to stop at the parallel and seek a negotiated truce.

In Tokyo his immediate superior General Douglas MacArthur, did not agree and let his opinion resound through the media. On April 11 Ridgeway was at the front in a snowstorm supervising final plans for an attack on the Chinese stronghold of Chörwön, when a correspondent said, “Well, General, I guess congratulations are in order.”

That was how he learned that Truman had fired MacArthur and given Ridgeway his job as supreme commander in the Far East and as America’s proconsul in Japan.

Ridgeway was replaced as Eighth Army commander by Lieutenant General James Van Fleet, who continued Ridgeway’s policy of using coordinated firepower, rolling with Communist counter punches, inflicting maximum casualties.

Peace talks and occasionally bitter fighting dragged on for another twenty-eight months, but there was never any doubt that EUSAK was in Korea to stay.

Ridgeway and Van Fleet built the ROK Army into a formidable force during these months. They also successfully integrated black and white troops in EUSAK.

Later, Ridgeway tried to combine his “profound respect” for Douglas MacArthur and his conviction that President Truman had done the right thing in relieving him.

Ridgeway maintained that MacArthur had every right to make his views heard in Washington, but not to disagree publicly with the president’s decision to fight a limited war in Korea.

Ridgeway, with his deep concern for the individual soldier, accepted the concept of limited war fought for sharply defined goals as the only sensible doctrine in the nuclear age.

After leaving the Far East, Ridgeway would go on to become head of NATO in Europe and chairrnan of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President Eisenhower.

Ironically, at the end of his career he would find himself in a MacArthuresque position. Secretary of Defense Charles E. (“Engine Charlie”) Wilson had persuaded Ike to slash the defense budget—with 76 percent of the cuts falling on the army.

Wilson latched on to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’s foreign policy, which relied on the threat of massive nuclear retaliation to intimidate the Communists. Wilson thought he could get more bang for the buck by giving almost half the funds in the budget to the air force.

Ridgeway refused to go along with Eisenhower. In testimony before Congress, he strongly disagreed with the administration’s policy.

He insisted it was important that the United States be able to fight limited wars, without nuclear weapons. He said massive retaliation was “repugnant to the ideals of a Christian nation” and incompatible with the basic aim of the United States, “a just and durable peace.”

EISENHOWER WAS INFURIATED, BUT RIDGEWAY STOOD HIS GROUND—and in fact proceeded to take yet another stand that angered top members of the administration. In early 1954 the French army was on the brink of collapse in Vietnam. Secretary of State Dulles and a number of other influential voices wanted the United States to intervene to rescue the situation.

Alarmed, Ridgeway sent a team of army experts to Vietnam to assess the situation. They came back with grim information.

Vietnam, they reported, was not a promising place to fight a modern war. It had almost nothing a modern army needed—good highways, port facilities, airfields, railways. Everything would have to be built from scratch.

Moreover, the native population was politically unreliable, and the jungle terrain was made to order for guerrilla warfare. The experts estimated that to win the war the United States would have to commit more troops than it had sent to Korea.

Ridgeway sent the report up through channels to Eisenhower. A few days later he was told to have one of his staff give a logistic briefing on Vietnam to the president. Ridgeway gave it himself.

Eisenhower listened impassively and asked only a few questions, but it was clear to Ridgeway that he understood the full implications. With minimum fanfare, the president ruled against intervention.

For reasons that still puzzle historians, no one in the Kennedy administration ever displayed the slightest interest in the Ridgeway report—not even Kennedy’s secretary of state, Dean Rusk, who as assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs in 1950–51 knew and admired what Ridgeway had achieved in Korea.

As Ridgeway left office, Rusk wrote him a fulsome letter telling him he had “saved your country from the humiliation of defeat through the loss of morale in high places.”

The report on Vietnam was almost the last act of Ridgeway’s long career as an American soldier. Determined to find a team player, Eisenhower did not invite him to spend a second term as chief of staff, as was customary. Nor was he offered another job elsewhere.

Although Ridgeway officially retired, his departure was clearly understood by Washington insiders as that rarest of things in the U.S. Army, a resignation in protest.

After leaving the army in 1955, Ridgeway became chairman and chief executive officer of the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, in Pittsburgh. He retired from this post in 1960 and has continued to live in a suburb of Pittsburgh. At this writing he is 97. [Editor’s note: Ridgeway died at age 98 on July 26, 1993.]

When Ridgeway was leaving Japan to become commander of NATO, he told James Michener, “I cannot subscribe to the idea that civilian thought per se is any more valid than military thought.”

Without abandoning his traditional obedience to his civilian superiors, Ridgeway insisted on his right to be a thinking man’s soldier—the same soldier who talked back to his military superiors when he thought their plans were likely to lead to the “needless sacrifice of priceless lives.”

David Halberstam is among those who believe that Ridgeway’s refusal to go along with intervention in Vietnam was his finest hour. Halberstam called him the “one hero” of his book on our involvement in Vietnam, The Best and the Brightest.

But for the student of military history, the Ridgeway of Korea towers higher. His achievement proved the doctrine of limited war can work, provided those fighting it are led by someone who knows how to ignite their pride and confidence as soldiers. Ridgeway’s revival of the Eighth Army is the stuff of legends, a paradigm of American generalship.

Omar Bradley put it best: “His brilliant, driving uncompromising leadership [turned] the tide of battle like no other general’s in our military history.”

Not long after Ridgeway’s arrival in Korea, one of the lower ranks summed up EUSAK’s new spirit with a wisecrack: “From now on there’s a right way, a wrong way, and a Ridgeway.” MHQ

THOMAS FLEMING is a historian, novelist, and contributing editor of MHQ. He is at present working on a novel about the German resistance to Hitler.

These guys a really good by the way! Grumpy

Well I thought it was funny! Grumpy

Switchblade

SwitchbladeUSA – -(AmmoLand.com)- Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) has introduced S.3264, the Knife Owners’ Protection Act of 2018 (KOPA) including repeal of the Federal Switchblade Act. This is a companion to the House KOPA bill, H.R.84, introduced last year. Originally conceived and authored by Knife Rights in 2010 and first introduced in 2013, KOPA will remove the irrational restrictions on interstate trade in automatic knives that are legal to one degree or another in 44 states, while also protecting the right of knife owners to travel throughout the U.S. without fear of prosecution under the myriad patchwork of state and local knife laws.

Sen. Wicker said, “I am pleased to introduce the Knife Owners Protection Act. This legislation would provide law-abiding knife owners the appropriate protection when transporting knives across state lines. It would also repeal the antiquated Federal Switchblade Act. I look forward to working with my Senate colleagues to advance this sensible policy for knife owners”

Knife Rights Chairman Doug Ritter said, “We are proud to have Senator Wicker leading the KOPA effort in the Senate, a bill that will actually protect traveling knife owners and repeal the archaic and useless Federal Switchblade Act. It is clear that Senator Wicker understands the plight of knife owners placed in legal jeopardy by the patchwork of knife laws they encounter traveling in America.”

Unlike S.1092, the problematic and seriously inadequate Interstate Transport Act that was recently marked up in committee and which is being promoted by one segment of the industry, S.3264 and H.R. 84 include a robust Right of Action that would actually provide real protections for knife owners that need these protections the most.

TAKE ACTION!

We need your help to gain additional co-sponsors. Please call or email your Senators and Representative and urge them to co-sponsor this commonsense legislation.

A Right of Action provides for persons unlawfully detained for transporting their knives properly secured in compliance with the act to seek financial compensation from a jurisdiction that ignores the intent of Congress to protect these travels. Without a strong right of action, there is no deterrent—biased and rogue jurisdictions like New York and New Jersey would have no incentive to follow the law. In a state like New Jersey, where knife law offences are felonies, it is especially critical to dissuade them from prosecuting law-abiding citizens.

Lacking a Right of Action, acting with impunity, without fear of any meaningful recourse from their law-abiding victims, these rogue jurisdictions will further persecute citizens who attempt to defend themselves from illegal, and unjust or misguided enforcement actions. A robust right of action holds jurisdictions financially accountable if they willfully ignore the law. A strong right of action causes jurisdictions to consider these adverse repercussions before they arrest or prosecute an individual that is protected under the act.

Ritter said, “ignoring the unfortunate lessons of the past and passing a knife transport bill without a robust right of action would be unconscionable and an extraordinary disservice to knife owners and the entire knife community. KOPA’s right of action provides the teeth needed to actually give real protection to knife owners.”

Ritter added, “The Federal Switchblade Act was an asinine idea when it was passed in 1958 in a wave of Hollywood-inspired politically motivated hysteria and has only become more irrelevant as time has passed. The majority of states have always allowed switchblade possession and with Knife Rights’ repeal of switchblade bans in 15 states in the past eight years, more than four-fifths of the states now allow switchblade possession to one degree or another. It is way past time to repeal this law that only serves to interfere with lawful trade and commerce.”

A FAQ on KOPA with additional details and background can be found at: www.KnifeRights.org/KOPAFAQ2017.pdf

TAKE ACTION!

We need your help to gain additional co-sponsors. Please call or email your Senators and Representative and urge them to co-sponsor this commonsense legislation. PLEASE use the EMAIL A FRIEND option after you email or call to ask your friends to support this effort!

You can use Knife Rights Legislative Action Center to easily email Congress: CLICK HERE to email your Senators and Representative.

Or, CLICK HERE to locate your Senators’ and Representative’ phone numbers. We have included a call script to make it easy.

About Knife Rights :

About Knife Rights :

Knife Rights (www.KnifeRights.org) is America’s Grassroots Knife Owners Organization, working towards a Sharper Future for all knife owners. Knife Rights is dedicated to providing knife owners an effective voice in public policy. Become a Knife Rights member and make a contribution to support the fight for your knife rights. Visit www.kniferights.org