Used guns are a great way to shop for a bargain-priced self-defense pistol. As we accept more modern guns with modern features, like rails, optics, and ambidextrous controls, we can find guns that lack those features for a relatively fair price. That’s why we’ve come to the classic carry gun corner to find you an option for a great handgun at a great price.

Table of contents

The Problem With Classic Carry Guns

Before I gush over some quasi-retro firearms, let’s be real here. There are some downsides to these classic carry guns. Most of them are heavier and bigger than modern guns. There is a reason that the P365 was so revolutionary. These older guns are not as efficient.

The biggest downside will come from trying to find a holster. Old guns aren’t typically addressed by modern holster manufacturers. This can limit you significantly in your holster selection. That can make carrying some of these classics a chore or require a custom holster to be made.

All that being said…

The Best Classic Carry Guns

Beretta 80 Series

Beretta recently revived the 80 series with the 80X, but the classic 80 series are still some classic carry guns. The 80 series is made up of a mix of .22LR, .380 ACP, and .32 ACP handguns. The most popular is the .380 Model, which consists of the 83, 84, 85, and 86 models. These are small, compact firearms but are not pocket pistols. They are incredibly well-made and very easy to shoot.

Their ergonomics are on point and are some of the best examples of what a metal-framed gun can be. They have that Beretta M9 style shape, with much thinner grips that make the gun easier to conceal and more accessible to those with small hands. They are hand-filling guns, and that makes them quite easy to control. Capacity varies between thirteen and seven rounds depending on caliber and design. Beretta made various models in both single and double-stack capacities.

The Beretta 80 Series seem out of date until you start shooting. They are all fairly light recoiling and very easy to control. They don’t beat your hand up like a .380 Pocket pistol and are much easier to control than even a P365 in 9mm. Guns like the Beretta 81 offer a .32 ACP option with very little recoil for those who might be recoil-sensitive. The .22LR options are silly soft to shoot. These are all top-of-the-line classic carry guns.

Beretta makes legendary firearms, and you’d have a hard time finding one that didn’t work well. These guns might be past their prime and seem old school, but they are very easy to handle and fun to shoot. They are more akin to the Shield EZ series, especially the 86 with its tip-up barrel.

The Ruger P Series

The P series might have been the series of firearms that established Ruger as a company that makes tanks for guns. They might be ugly, but they are 100% functional, incredibly reliable, and last forever. The Ruger P series guns are still kicking around and are still quite affordable. I run across these guns for less than 300 dollars all day long, and they still represent self-defense-worthy handguns.

The P series is fairly broad. You can pick from numerous models in various calibers, including 9mm, 40 S&W, and .45 ACP. The P Series lasted from 1985 all the way up to 2013. Over that time, there were tons of variants. The P85 through P944 used investment cast metal frames, and the P95 and beyond used a polymer frame. The modern polymer frame models also feature a rail system.

These are pure ’80s guns. They feature the hammer fire design that was popular for the era. The gun has a combined de-cocker and safety that was ambidextrous. They are fairly simple guns but were quite easy to shoot and handle. The guns feature modern capacities and, outside of the .45 ACP, used double-stack magazines.

They aren’t fancy, they aren’t pretty, but they do function well. If you can get past their blocky design and ugly frames, you can have a very capable firearm for very little money. I’d choose a Ruger P series over most modern budget options. If you are looking for a more carry-friendly option, the P94 and P95 offer compact options for a tank-like classic carry gun.

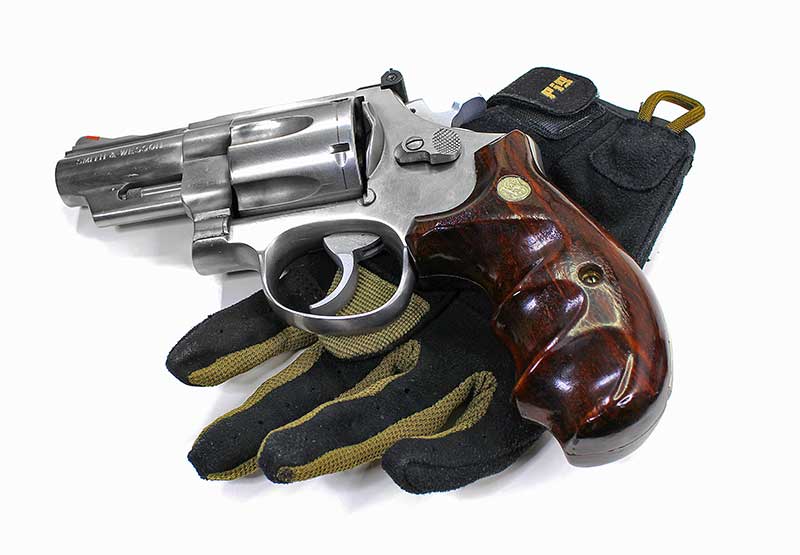

Smith and Wesson 3rd Gen Guns

Smith and Wesson produced a number of semi-auto handguns from 1913 onward, and in the late 1980s, they arrived at what is collectively known as the third-generation pistols. These represent the last line of S&W automatics to use all metal frames, DA/SA hammer-fired actions, and a mix of double and single-stack magazines. They were quite popular with police forces and remain a great option these days.

Some are more expensive than others. The S&W 1006 and 1026 in 10mm, for example, are not cheap options. However, the 5906, the various 900 series guns, and even the 4506 tend to be fairly affordable and easy to find. These third-gen guns come in all the big calibers, including 9mm, 45 ACP, 40 S&W, and, of course, the aforementioned 10mm. What’s a gun from the late 80s and early 90s without a 10mm chambering?

These heavy steel guns might weigh you down a fair bit, but they can still be fantastic classic carry guns and home defense options. S&W produced some small subcompact models, including the various 9mm subcompacts like the 908 and 3914, and basically every model that starts with 39. These are still quite compact, and while unusual in today’s era, they still last for basically ever.

If you find a lack of Picatinny rails disturbing, then the TSW models might be for you. These guns feature a nice metal rail for all the accessories you could ever need, but the TSW models tend to call for a higher price on the used market.

Smith and Wesson SW99 – Classic Carry Option

Let’s stick with S&W because they’ve been around a long time, and they have a wide variety of pistols in their lineup. In the late 1990s, it was apparent that polymer-frame, striker-fired guns were going to be the dominant force in firearms. S&W had already tried to produce one in the budget-friendly Sigma series but got sued by Glock. Plus, the Sigma series weren’t duty-ready guns. S&W teamed up with Walther to produce an S&W pistol.

Kind of an S&W pistol, anyway. It’s a Walther P99 with a standard rail. The SW99 and P99 are nearly identical, and the SW99 came in both 9mm and 40 S&W, like the P99, but the SW99 also got the 45 ACP. These polymer frame pistols were a joint effort. Walther made the frames, and S&W made the slides and barrels. Like the P99, these are one of the very few DA/SA guns that are striker-fired. A decocking button sits on the top to instantly toss it back to double action only.

The SW99 trigger is absolutely fantastic. The DAO is super smooth, and while heavy, it glides rearward. The single action is crazy light and absolutely fantastic. It’s a great setup that I wish was a bit more common. I really like the striker-fired DA/SA design. Sadly, the SW99 is one of the very few options out there.

What’s great is that the SW99 remains affordable. Walther fans want P99s, and guns like the P99 compact are fairly tough to find. However, the SW99 compact is easy to find and fairly cheap. These guns use Walther mags, and they tend to be fairly common. This is one of my favorite classic carry guns.

Glock Trade-Ins

Finally, another great option is the great many Glock police trade-ins out there. Glock pistols dominate the law enforcement market, and with a new generation of Glock getting out there and with competition from SIG, used Glocks are hitting the market hard. Glocks are great guns that last forever and are well-reputed for their durability, reliability, and general effectiveness.

A lot of these Glock pistols are the .40 S&W models that have been traded in for the great 9mm influx. Plenty of Glock 22s are floating around at a great price. Additionally, the Glock 23 and 27 are popular trade-ins. In 40 S&W, these guns can be found for less than 400 dollars. That’s a great price for a very reliable weapon, even if you have to deal with 40 S&W.

With that said, we do see some 9mms coming in and out, and these are great grabs. The desirability of 9mm does create an increased cost, but they are still fairly affordable firearms all around. Glock trade-ins are a great way to get a great handgun for a low price. If you see one, act quickly because they tend to sell fast.

Giving Used Guns a Chance

The used gun market is nothing like other used markets. Used cars can be a gamble. Used furniture is for the insane, but used guns are a great choice. When something is wrong, it’s easy to see. Cracks in frames, bad bores, and the like don’t hide easily. Typically, used guns are rarely shot, but they often have a chunk of their price squirreled away.

A used gun allows you to get a great gun at a budget gun’s price. Sure, they might not always have rails, night sights, or be optics ready, but they go bang and do so reliably.