Category: Ammo

Nitrous Oxide Shotgun Slugs – We test them!

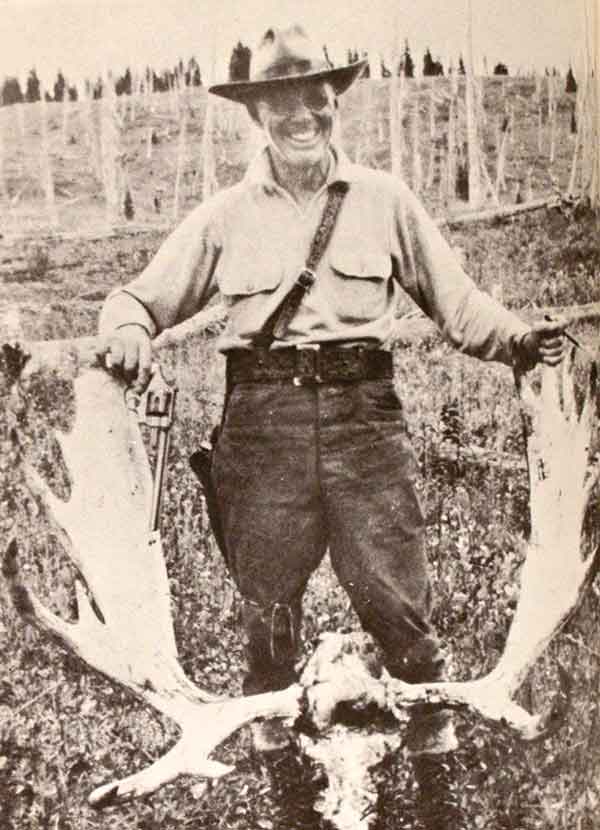

It wasn’t long before experimenters came up with even heavier loads for the .38/44. In 1932, Ed McGivern had high praise for both the revolvers and the new cartridge. He spoke of shooting the Outdoorsman out to 500 yards and called it the finest gun ever turned out by anybody at any time. The .38/44 Heavy Duty was considered “… the finest, strongest, all around general-purpose gun, coming from all angles, that has ever been given to the shooting public.” Experimenters like Elmer Keith and Phil Sharpe came up with much heavier loads and Keith’s .38/44 load is still a standard today among sixgunners.

The Beginning

The S&W .38/44 Outdoorsman made the .357 Magnum possible and the latter really started in the hunting fields. Sharpe, in his monumental work, Complete Guide To Handloading, published in 1937, said, “The .357 Magnum cartridge was born in the mind of the author several years ago. On a hunting trip with Col. D.B. Wesson, Vice-President of Smith & Wesson, a pair of heavy framed Outdoorsman revolvers was used with a large assortment of handloads developed and previously tested by the author. In the field they proved entirely practical, but Col. Wesson was not content to attempt the development of a Magnum .38 Special cartridge for ordinary revolvers, and set to work on a new gun planned in the field.”

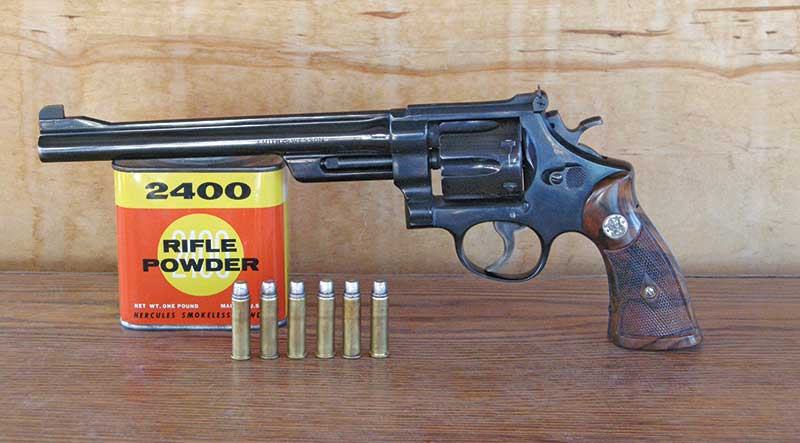

In 1935 their work with the .38/44, as well as, by ammunition companies, resulted in a new cartridge. The .38 Special case was lengthened and a new name was needed. Wesson, of Smith & Wesson, used the diameter of the bullet, .357″ and the French word for a large bottle of champagne, Magnum, and the .357 Magnum arrived. The original load was 15.4 grains of Hercules 2400 under a 158-grain lead bullet and ignited by a large—not small—primer.

The first Magnum sixgun, known appropriately as “The .357 Magnum” was born. The .357 Magnum sixguns were more than simply production guns. Each of the new .357s were specially fitted and finished, and given a registration number in addition to a serial number. In 1935, in the midst of the Great Depression, the new sixgun and cartridge were so popular Smith & Wesson soon dropped the special registration, as they could not keep up with the demand. Back then, $60 was a lot of money, but many shooters were more than willing to pay it to get the finest revolver ever made up to that point.

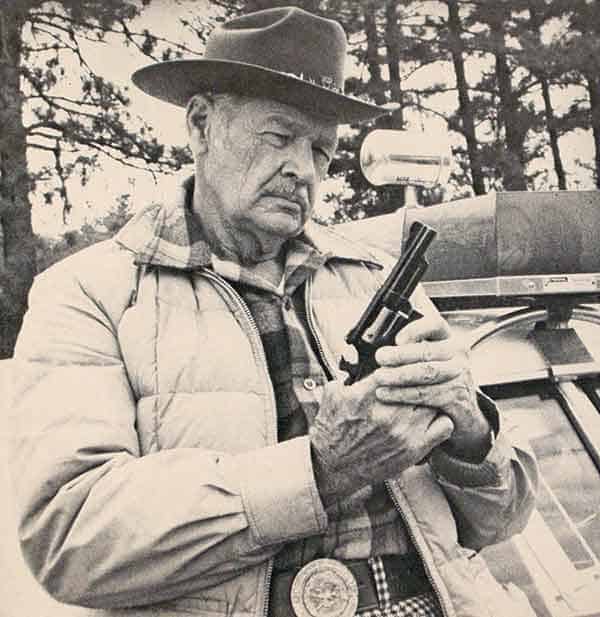

Remember, 1935 was long before the age of instant communication or even gun magazines, except the American Rifleman. Elmer Keith wrote up the .357 for the latter, but opined the barrel was too long and he still preferred the .44 Special. Wesson promoted the new gun and cartridge using both a 6-1/2″ and 8-3/4″ .357 Magnum-taking elk, antelope and black bear. He even went to Alaska with the hopes of taking a brown bear, but was unable to find one. After contemplation, he felt it was a good thing he had not done so. In later years both of these early .357 Magnum, revolvers were owned by Col. Rex Applegate, and it was my privilege to be able to handle them. After his death they were sold, so they now belong to a Smith & Wesson collector somewhere.

Keith’s .38/44 load used his 173-grain 358429 hardcast bullet, which proved too long for use in the .357 Magnum cartridge due to the length of the Smith & Wesson cylinder. Sharpe designed a 158-grain bullet with a shorter nose and less bearing surface for use in the new cartridge, and published extensive reloading data while warning reloaders not to take this cartridge for granted. In the early 1950s it was left to Ray Thompson to come up with the ideal bullet for the .357 Magnum with his gas-checked 358156. Leading was always a problem with both factory and reloads for the .357 Magnum until Thompson solved the issue. I have never been able to get really good accuracy using plain-based bullets in full-house .357 Magnum loads, but the Thompson gas-checked bullet works perfectly. I consider it the number one bullet for standard weight loads in the .357 Magnum.

The FBI Gun

Smith & Wesson advertised the .357 Magnum as the most powerful revolver ever made, far above any .44 or .45 available. It was not only promoted by Col. Wesson, but Smith & Wesson was also wise enough to present one of the first production 8-3/4″ .357 Magnums to the then head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover. That barrel length was, of course, too long for law enforcement use, however, 4″ and 3-1/2″ .357 Magnums soon became very popular with FBI agents.

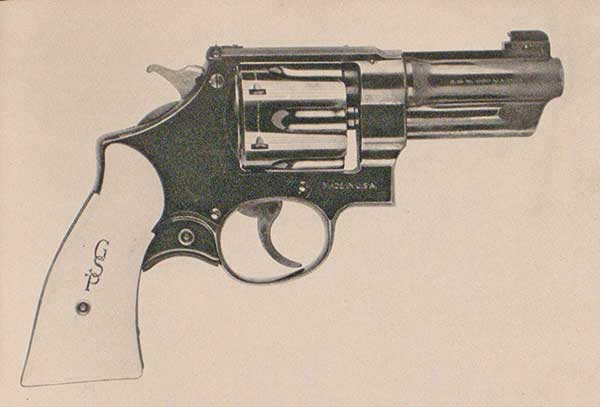

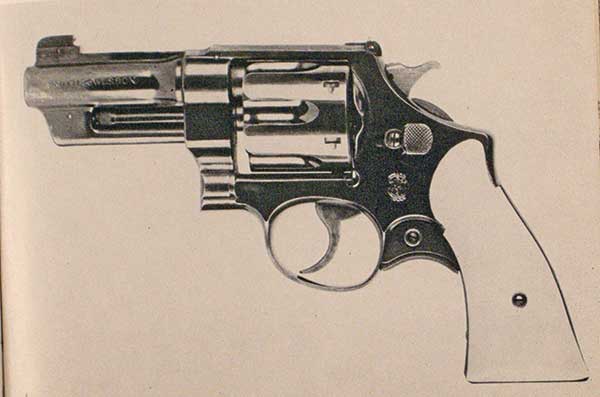

Soon-to-be General George Patton purchased a 3-1/2″ .357 Magnum in Hawaii in 1935 and carried it in tandem with his Colt Single Action .45 during World War I. He called the Smith & Wesson .357 his “killing gun.” Even though both his Colt and Smith & Wesson wore ivory grips, contrary to popular belief, they were not finished the same. The Colt was engraved and nickel-plated, while the Smith & Wesson was plain high-polish blue. https://gunsmagazine.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=29220&action=edit#

Those early .357 Magnums may very well be the finest revolvers to ever come from the Smith & Wesson factory. From 1935 to 1939 approximately 5,200 “Registered Magnums” were manufactured. These guns were basically handfitted, beautifully polished and, in addition to a serial number, had a second number, a registration number, placed on the yoke cuts. Patton’s .357 Magnum carried registration No. 506. Registration No. 1 went to Hoover and No. 2 to Sharpe.

Barrel lengths in order of preference were 6-1/2″, 5″, 6″, 8-3/4″, 3-1/2″ and 4″. In 1939 Smith & Wesson dropped the registration procedure and barrel lengths were standardized at 3-1/2″, 5″, 6″, 6-1/2″ and 8-3/8″, not necessarily in order of preference. All of these guns had a beautiful high bright-blue finish (nickel was an extra option) with a fine-line checkering on the barrel rib, top strap and rear sight assembly. Both the backstrap and the frontstrap were serrated and the first grips/stocks were the small old-style found on all N-frames since late 1907. The .357 Magnum was the first Smith & Wesson to be fitted with Magna stocks, which were soon offered as an option. These filled in on both sides of the grip frame to the top of the backstrap.

Of course, production of the .357 Magnum and all other firearms stopped at the beginning of WWII as machinery was geared up for wartime production. After the war, it would be December of 1946 before another .357 Magnum would be produced, and only 142 were manufactured through 1949. One of these went to President Harry Truman. Obviously, .357 Magnums were hard to find.

Debut Of The Short Action

In 1950 the long action of the .357 Magnum was changed to the current short action, which allowed a shorter distance for the hammer to travel. Skeeter Skelton often remarked how hard it was to find a .357 Magnum in the 1950s. When I started really getting interested in gunshops in 1956, I don’t recall ever seeing any. In fact, I saw the .44 Magnum first.

In 1956, the upper sideplate screw was deleted and the “5-screw” .357 Magnum became a “4-screw” with three screws in the sideplate and one in the front of the triggerguard. One year later, this magnificent revolver, which had been known only as the .357 Magnum since its inception, now became a number instead of a name: the Model 27. Four years later, the screw in the front of the triggerguard was eliminated and the Model 27 became a “3-screw” sixgun.

In 1994 the unbelievable happened, and the .357 Magnum, the Model 27, was dropped from production. However, it was not forgotten and just before the end of the 20th century a new Model 27 appeared. This Performance Center gun bears little resemblance to the original with an 8-shot cylinder and a heavy tapered underlugged barrel. It is a good sixgun, but simply not the same. Just recently, in their Classic Series, Smith & Wesson reintroduced the Model 27 in time for its Diamond Anniversary.

The .357 Magnum, as mentioned, was a beautifully finished revolver, so beautiful in fact, some were reluctant to carry it as a duty gun. In 1954, to answer this “problem,” Smith & Wesson brought out a special version of the .357 Magnum known as the Highway Patrolman. This was a basic no-frills .357. No high polish here as the finish was a matte blue, and also gone was the fine checkering on the top strap. Barrel length was 4″ or 6″ and Magna stocks were standard. The first new Smith & Wesson I ever purchased was a 4″ Highway Patrolman. In 1957 the Highway Patrolman became the Model 28.

Now we had a less fancy .357 Magnum for duty and outdoor use. What’s next? Bill Jordan began petitioning Smith & Wesson to produce a lighter weight .357 Magnum using the Military & Police .38 as the basic platform. In 1955 Smith & Wesson unveiled the .357 Combat Magnum. Using the K-frame .38, a full-length .357 Magnum cylinder was installed matched up with a 4″ bull barrel. The result was a revolver Bill Jordan called “The Peace Officers Dream.” Weighing a full 1/2-pound less than its older brother and with a smaller cylinder diameter, the Combat Magnum was much easier to carry all day.

In 1957 the Combat Magnum became the Model 19. Somehow, .357 Magnum, Highway Patrolman and Combat Magnum stir the sixgunning soul a whole lot more than 27, 28 and 19! In 1963 a 6″ version was introduced for the Model 19, followed by a 2-1/2″ in 1966. In 1970, the Model 19 was produced in stainless steel with the same barrel lengths, and was called the Model 66. In 1999, the Model 19 was dropped, and the Model 66 received the same fate in 2005. Long before they disappeared, they had basically been replaced by the stronger L-Frame, heavy under lugged–barreled Models 586 and 686.

Prior to World War II, Colt chambered their New Service, Shooting Master and Single Action Army in .357 Magnum. Production ceased in 1940. However, in 1954 Colt introduced their .357 Magnum followed by the Python, their Cadillac of revolvers, in 1955, and in 1956, the Colt Single Action Army returned in .357 Magnum.

Ruger’s first centerfire sixgun was the .357 Blackhawk in 1955. This was a true outdoorsman’s sixgun with adjustable sights, a heavy top strap and a Colt-sized grip frame. Since that time, both companies have introduced several other .357 Magnums, including the underrated Ruger GP100 and Colt King Cobra, and we have also seen .357s from manufacturers such as Freedom Arms, Dan Wesson and Taurus.

The .357 Magnum remains extremely popular and is probably the most powerful revolver most shooters can handle really well. We have a long list of revolvers chambered in the original Magnum available today. However, my heart still belongs to the old classics, and especially to the original .357 Magnum. With the Lyman/Thompson 158-grain gas-checked bullet over 14 to 15 grains of 2400 loaded in any of the above, life is quite pleasurable. Happy 75th anniversary to the Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum.

Smith & Wesson

2100 Roosevelt Avenue

Springfield, MA 01104

(800) 331-0852, www.smith-wesson.com

BluMagnum

2605 East Willamette Avenue

Colorado Springs, CO 80909

(719) 632-9417, www.blu-magnum.com

Herrett’s STOCKS

P.O. Box 741, Twin Falls, ID 83303

(208) 733-1498, www.herrettstocks.com

Keith Brown Grips

3586 Crab Orchard Avenue

Beavercreek, OH 45430

(937) 426-4147

www.kbgrips.com

Any debate about the quintessential American hunting rifle would be incomplete without a mention of a lever-action rifle chambered in .30-30 Winchester.

The .30-30 was originally known as the .30-30 WCF (Winchester Centerfire Cartridge), which indicated that the round had a .30 caliber bullet sitting in front of 30 grains of then-new smokeless powder.

Debuting in Winchester’s 1895 catalogue paired with the iconic Model 1894 lever-action rifle, the round became wildly popular with hunters across North America, remaining a widely used hunting cartridge to this day.

In light of the cartridge’s age and the advent of newer, more advanced cartridges, one might wonder, “Is the .30-30 still any good?”

The answer is a resounding “yes!” While true that newer cartridges like the 6.5 Creedmoor and 300 PRC have undeniable advantages over the .30-30 in some areas, the old classic still has its place.

In many parts of the country, such as the Southeast, medium game such as Whitetail are encountered inside 200 yards and often in thick brush. A .30-30 lever-action rifle excels in these conditions, being easily maneuverable and able to deliver quick follow-up shots when needed.

The .30-30 delivers projectiles weighing between 110 and 170 grains at velocities ranging from 2200 fps to 2700 fps, providing more than enough energy to take medium game at 200 yards and closer.

The restricted range is partially due to the fact that .30-30 is most commonly a lever-action rifle cartridge, and therefore most ammunition uses a flat nose bullet that doesn’t run the risk of setting off the round in front of it in the rifle’s tubular magazine. An exception to this is Hornady’s Leverevolution line of ammunition, which makes use of a modern, more aerodynamic Spitzer-style bullet that is safe to use in lever action rifles. These rounds greatly reduce drag and deliver greater energy at longer ranges relative to the more traditional, flat nose variety of bullet.

Lever-action rifles chambered in .30-30 continue to be very popular. Both Henry and Marlin have introduced updated versions of their classic rifles that feature threaded barrels, picatinny rails for optics, and other accessory mounting options.

While it might not be taking elk at 600 yards, I suspect that, thanks to modern ammunition and continued manufacturer support, the .30-30 will be filling American freezers for many years to come, just as it has done since 1895.

What do you think about the old .30-30? Share this out to your social media of choice and let us know!

Duke’s altered Model 1886 .40-82 (top) with a 20″ barrel shown for comparison

with a new Japanese Winchester Model 1886 .45-70 with its standard 26″ barrel.

Naturally we clearly remember the “firsts” in our lives — first gun, first car, first date, etc. I remember fondly my first experience with an antique lever gun because it started my career on a path still followed today: learning the ins and outs of safely shooting old and obsolete guns and their cartridges.

Back in the late 1970s a friend, knowing of my handloading and bullet casting experience, asked if I would load some .40-82 cartridges if he supplied brass, dies and bullet mold. His lever gun was a nice Winchester Model 1886 .40-82 manufactured in the late 1880s. It was a family heirloom but had not been fired in decades due to the lack of factory ammunition. His request sounded like an easy way to introduce myself to Winchester lever guns. The experience turned out to be more complicated, but more educational, than expected.

The Loads

The mold supplied was an Idea/Lyman #406169 which dropped a 0.408″ bullet weighing 260 grains of the wheel weight alloy I had on hand. I lucked out because the groove diameter of old .40-82 measured 0.408″ instead of the nominal 0.406″. Cases supplied were RCBS .45 Basic with a length of 3.25″. Those were hacksawed to just over the .40-82’s length of 2.40″ then trimmed to the final spec. Next, a now-forgotten charge of a likewise forgotten smokeless powder was dumped in 20 cases. Bullets were seated and crimped and I was ready to shoot.

Only I wasn’t! The rounds were too fat to chamber. It had not occurred to me the .45 basic case walls increased in thickness from case mouth to case rim. Thinning the case walls was the cure so RCBS tooling for the chore was acquired. Again I thought everything was a go. It wasn’t. Every shot fired gave a click-bang. The click was the hammer falling. The bang was the powder charge firing a second or so later, meaning it wasn’t igniting properly. At least the bullets passed through paper targets point on. Some research revealed an old remedy for poor powder ignition was to fill the case atop the powder charge with corn meal. The fix worked and the old rifle began to shoot beautifully. In fact we took it hunting and I shot an elk with it.

Collecting

As I began to assemble an array of vintage Winchesters, for my own Model 1886 slot I wanted a .40-82. What I finally landed was one made in 1887 as indicated by its serial number. However, it was not a prime specimen. Its buttstock and receiver actually were very nice and it even had a Lyman No. 21 side-mounted peep sight. The problem was the barrel. While bore condition was very good, it had been shortened from 26″ to 20″ with the magazine tube cut correspondingly. Also, someone had roughly filled the original barrel sight’s dovetail and cut another one a few inches ahead of it but left it empty. Because of those problems the price was right.

Cleaning Up

In my mind the idea was to restore it someday with an intact .40-82 barrel and magazine tube. In the meantime I wanted to enjoy shooting it. Times had changed a bit. I knew to slug the barrel first — it was a whopping 0.409″, so I had custom mold maker Steve Brooks (brooksmoulds.com) cut a set of blocks for a 0.410″ bullet with a gas check shank. From my favorite 1–20 tin to the lead alloy I favor, the mold dropped them a mite heavy at 280 grains. A batch of .45 Basic cases were cut and inside reamed as before.

Between my first .40-82 and the one I purchased there was a new smokeless powder introduced. The powder was Accurate 5744 and it revolutionized all my thinking about smokeless powders in voluminous cases. Because it easily ignites in large cases there is no filler necessary. To my great pleasure, 100 yard groups from my .40-82 were outstanding from the very beginning. When I pull the trigger properly, most are in the 2″ to 3″ range at 100 yards. My favored 5744 charge of 25 grains pushes those 280-gr. bullets out at about 1,390 fp. All ideas about getting a replacement barrel for my cut down ’86 were forgotten.

Other shooters might prefer more glamorous ’86 chamberings like .45-90 or .50-110. I’ve even had such but it’s the .40-82 I’ve kept.