Category: Ammo

The British firm of John Rigby & Co. is older than the United States. Founded in 1775 by John Rigby, the Dublin, Ireland, gunmaker manufactured elegant flintlock rifles and pistols. Some 23 years later, Rigby’s facility was raided by Town-Major Henry Sirr and police force. Virtually every firearm in his place was seized and kept for a lengthy time. By the time they were returned, the firearms were virtually worthless, most having been disassembled and cannibalized for parts.

In 1816, Rigby, now 58 years old, brought his son, William, in as a partner. Two years later, John Rigby died, and William brought in his brother, John Jason Rigby, into the business. The brothers ran it—now called W&J Rigby—until 1887 when John Jason was appointed superintendent of the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock. The Rigby name was always identified with the finest quality in firearms, and as the 19th century came to a close, firearm technology was skyrocketing.

Cordite—a double-based smokeless propellant that looks similar to spaghetti—was patented in Britain in 1889. The burn rate of Cordite was modified by the surface area early on. Thin strands burned at a faster rate, while thicker strands had a slower rate of deflagration. Big-game hunting was still popular among the privileged class, but those gorgeous examples of the gunmaker’s art—double rifles—were terribly expensive.

Cordite—a double-based smokeless propellant that looks similar to spaghetti—was patented in Britain in 1889. The burn rate of Cordite was modified by the surface area early on. Thin strands burned at a faster rate, while thicker strands had a slower rate of deflagration. Big-game hunting was still popular among the privileged class, but those gorgeous examples of the gunmaker’s art—double rifles—were terribly expensive.

Too, the idea caught on among some that a magazine rifle could hold more cartridges and therefore be rather valuable when things went sideways with an animal that can bite, claw or stomp a hunter, as well as his entourage, in the event of a poorly placed shot. However, magazine rifles can be problematic in feeding the rimmed cartridges used in double rifles. W.J. Jeffery & Co. and Westley Richards each came out with proprietary heavy-game cartridges in 1905 and 1909, respectively.

The .404 Jeffery was initially loaded with either a 300-grain bullet at 2,600 f.p.s. with 4,500 ft.-lbs. of energy or a 400-grain bullet at 2,150 f.p.s. and 4,100 ft.-lbs. of energy. Westley Richards developed a .425 Westley Richards launching a 410-grain bullet at 2,350 f.p.s. with 5,010 ft.-lbs. of thump. Each of these cartridges easily outshined the .450 Black Powder Express cartridge that they replaced. The .425 Westley Richards features a rebated rim , allowing it to be built on a standard .30-’06 Sprg. length Mauser 98 action.

The .404 Jeffery was initially loaded with either a 300-grain bullet at 2,600 f.p.s. with 4,500 ft.-lbs. of energy or a 400-grain bullet at 2,150 f.p.s. and 4,100 ft.-lbs. of energy. Westley Richards developed a .425 Westley Richards launching a 410-grain bullet at 2,350 f.p.s. with 5,010 ft.-lbs. of thump. Each of these cartridges easily outshined the .450 Black Powder Express cartridge that they replaced. The .425 Westley Richards features a rebated rim , allowing it to be built on a standard .30-’06 Sprg. length Mauser 98 action.

The .404 Jeffery needed a Magnum Mauser action to accommodate its overall length. John Rigby wasn’t sitting on the sidelines. In 1897, he negotiated an agreement with Mauser-Oberndorf to be the exclusive source for all Mauser-made rifles, barreled actions and parts in Great Britain; an arrangement that extended into the first 40 years of the 20th century. Rigby then set about designing a cartridge that worked well in a bolt-action magazine rifle and perform as well or better than the Jeffery and Westley Richards cartridges.

He started from scratch—no parent case and no existing bullet—a rather expensive way to develop a new cartridge. Rigby’s cartridge turned out to be slightly rebated-rim case, 2.900″ long, .589″ in diameter at its base tapering to .540″ at the shoulder with a bullet diameter of .416″. Such a huge case could only be contained in a Magnum Mauser No. 5 receiver. Rigby’s magnum magazine rifle was an instant success, though the raw numbers made it seem paltry. This was a custom rifle for those who traveled the world in search of big game, so rifle and cartridge were proprietary.

He started from scratch—no parent case and no existing bullet—a rather expensive way to develop a new cartridge. Rigby’s cartridge turned out to be slightly rebated-rim case, 2.900″ long, .589″ in diameter at its base tapering to .540″ at the shoulder with a bullet diameter of .416″. Such a huge case could only be contained in a Magnum Mauser No. 5 receiver. Rigby’s magnum magazine rifle was an instant success, though the raw numbers made it seem paltry. This was a custom rifle for those who traveled the world in search of big game, so rifle and cartridge were proprietary.

Too, while the magazine rifle was popular because of its cost—about half that of a double rifle at that time—and lighter weight, Rigby still continued to crank out double rifles for those who wanted the best and could afford it. From 1912 until World War II, Rigby turned out just 169 rifles on the Magnum Mauser receiver. Over the following 59 years, just 364 copies were built. A resurgence of interest in the .416 Rigby rifle and cartridge came from Jack O’Connor in the 1960s.

The .416 Rigby, left, is shown next to a .375 Holland & Holland cartridge.

O’Connor had a .416 made up on a Brevex Mauser receiver and took it to Africa. He found it a very effective cartridge for heavier game, with less recoil than the .450 Watts O’Connor used on previous hunts on the Dark Continent. In his The Rifle Book—a must-have tome for any serious student of the hunting rifle—O’Connor said, “[The .416] is an outstanding cartridge…drives a 410-grain bullet, according to claims, at a velocity of 2,371 and turns up 5,100 ft.-lbs. of energy.” O’Connor was a gifted wordsmith and shared compelling stories of adventure with his rifles around the world.

It was these tales that fueled new interest in both the rifle and .416 Rigby cartridge. While the interest was strong because of more people heading into big game country, ammo was still a sticking point. Kynoch had been the sole supplier of .416 Rigby ammunition until the 1970s, and the company was twisting in the wind by that time. It would later rise again as a British company with a separate U.S. base. Ruger introduced the .416 Rigby in 1991 in its Model 77 RSM Magnum Mk II rifle. Now nearly anybody could have a solid .416 Rigby rifle, and ammunition manufacturers took note.

Federal, Hornady and Norma tooled up and began producing .416 Rigby ammunition. Later, Nosler and Winchester began loading the .416 Rigby. The British firm of Eley licensed rights for the Kynoch name to Kynamco, a British firm, in Suffolk, England, and rekindled .416 Rigby ammo under its original name. Today’s loads in .416 Rigby feature 400- to 410-grain soft-nose or FMJ bullets at 2,300 to 2,400 f.p.s. and churning up some 4,700 to 5,100 ft.-lbs. of energy and have a maximum-point-blank range of 198 yards.

Compare that to the .458 Winchester Magnum with a 500-grain bullet at 2,050 f.p.s. and 4,665 ft.-lbs. of energy. The .416 Rigby may have started from scratch, but it has spawned several notable progenies. Such uber-mags like the .300 and .338 Lapua cartridges are based on the .416 Rigby case, as are the .450 Dakota, .450 Rigby and .500 Whisper. Weatherby’s .30-378, .338-378, .378, .416 and the .460 Weatherby Magnums may have a belt—almost a trademark of Weatherby cartridges—but dimensionally each can be traced back the Rigby’s original case.

As a sporting cartridge, the .416 Rigby may not be as popular as the .30-’06 Sprg. or .375 H&H, but that’s normal. Not every hunt is for huge animals that can and will stomp you back if you mess up a shot. Too, it’s not something any sane person would want to shoot 200 rounds of it in a day of shooting. Besides the recoil, cartridges are more than $5 per round. But for serious work on dangerous game, the .416 Rigby remains in a class by itself.

32 Remington Model 14

In 1899, a group of Moro tribesmen in the Philippines took umbrage toward a United States occupation force in the southern islands, thereby initiating what became known as the Moro Rebellion. The Moros were fierce fighters, with a reputation of resistance toward any outside rule. Officers in the U.S. force were armed with Colt Model 1892 revolvers chambered in .38 Long Colt, a cartridge that originated the blackpowder era. The load at the time featured a 150-grain lead round-nose bullet launched at 750 f.p.s. using smokeless powder. Muzzle energy was 201 ft.-lbs., about the same energy as a .380 ACP with a 90-grain bullet.

The Moros were reputed to tie themselves up with strips of vegetation from the jungles to prevent excessive bleeding and ingested locally made drugs to block the pain from wounds. Engagements involving the Colt double-action Model 1892 often resulted in the officer being killed or severely wounded by these motivated Moro juramentados. This prompted the War Department to launch the Thompson-LaGarde Tests of 1904. As expected, the rather grisly tests showed the .38 Long Colt significantly lacking in the power needed to stop a determined assailant. The tests determined that what was needed were the ballistics of the .45 Colt in a more compact round. Semi- and full-automatic arms were being developed, and the old .45 Colt would not function in the new pistols.

Colt and John Moses Browning were developing a .41-cal. cartridge in a semi-automatic pistol in 1904. As a result of the Thompson-LaGarde Tests, the Ordnance Department specified a .45-cal. cartridge, and Browning obliged the department with a .45-cal. Model 1905 pistol. Browning and Colt continued to refine the design, and on March 29, 1911, the Colt Model 1911 pistol and the “Cal. 45 Automatic Pistol Ball Cartridge, Model of 1911″—now known as the .45 ACP—were formally adopted by the Army.

Remington 230-grain JHP .45 ACP loads (left), compared with Winchester 230-grain ball loads.

Remington 230-grain JHP .45 ACP loads (left), compared with Winchester 230-grain ball loads.

Winchester, Frankford Arsenal and the Union Metallic Cartridge Co. had been working on the loads for the new pistol cartridge. At the time of the trials, these ammo companies were loading a 200-grain full metal jacket (FMJ) bullet with a velocity of 900 f.p.s. This load passed the tests, but later, it was modified to have a 230-grain FMJ round traveling at 850 f.p.s. The first cartridges sent into service came from the Frankford Arsenal and were headstamped “F A 8 11,” for the August 1911 date.

Both cartridge and pistol enjoyed immediate success—too much, in fact, because as World War I came along, demand far outstripped availability. Both Smith & Wesson and Colt were forced to ramp up their large-frame revolver production chambered for the .45 ACP during World War I. These revolvers relied on “half-moon clips” to provide for simultaneous extraction and ejection of the rimless cases from the cylinder. After the war, the Peters Cartridge Company added a thick rim to the .45 ACP, calling it the .45 Auto Rim. It is ballistically and dimensionally identical to the ACP cartridge, save for the rim. This development was the result of thousands of surplus Model 1917 Smith & Wesson and Colt revolvers being dumped onto the surplus market.

The reason for the success of the .45 ACP cartridge is simple. It works. People shot with it “stay shot,” as it is often said. A 230-grain, .45-cal. bullet with proper placement is capable of effectively putting an assailant down. The .45 ACP cartridge also has the very desirable characteristic of being inherently accurate. A properly tuned semi-automatic pistol or revolver can often put five shots into a ragged hole at 25 yards.

A Smith & Wesson Model of 1917 service revolver chambered for .45 ACP.

A Smith & Wesson Model of 1917 service revolver chambered for .45 ACP.

For several decades, the M1911 pistol and .45 ACP cartridge had an undeserved reputation for being difficult to shoot. Early pistols were loosely fitted in order to keep them running in wartime environments of mud, dust and sludge. Pistols with a lot of free tolerances do not group as well as those that have had those tolerances tightened up. Of course, fitted pistols need to be kept clean and lubricated to maintain their reliability.

Any U.S. military cartridge is going to have some built-in popularity due to the surplus market. Surplus guns and ammunition are often heavily discounted, and when that gun and cartridge were the staple of the U.S. military and many law-enforcement agencies for 71-plus years, the result is that the .45 ACP is almost universally available.

The popularity of the .45 ACP was not limited to the M1911 pistol. The cartridge has been chambered for semi-automatic pistols made by Browning, Colt, Heckler & Koch, Ruger, SIG Sauer, Smith & Wesson, Taurus, Walther and many more. Colt and Smith & Wesson have been joined by Ruger and Taurus, as well as many Italian replica manufacturers, in creating revolvers chambered for the .45 ACP, both single action as well as double action. Carbines and submachine guns emerging after the famous Thompson have been chambered in .45 ACP. Micro pistols like the Semmerling LM4 and the Liberator were also chambered for the cartridge. It is safe to state that the .45 ACP is ubiquitous.

Two .45 Auto Rim cartridges, designed to work in revolvers like the S&W Model 1917 without the need for moon clips.

Two .45 Auto Rim cartridges, designed to work in revolvers like the S&W Model 1917 without the need for moon clips.

Handloading the .45 ACP is pretty straightforward, provided you don’t try to turn it into a magnum. Bullets—both cast and jacketed—are available from 118 to 250 grains, and when shoved by a medium-fast powder like Alliant’s Unique, Winchester’s W231 or IMR’s SR 4756, they provide good results. One note of caution, however, is that some .45 ACP brass has been made with small primer pockets. If you want to avoid suddenly ceasing your loading operation to pick out components from your reloading tools and punctuating that chore with loud profanities, make sure you separate small primer pockets from large primer pockets beforehand.

Factory ammunition runs an equally diverse profile, with everything from lightweight hollow points to monolithic solids and even some snake-shot loads. The length and breadth of what the .45 ACP is capable of doing is impressive.

Yes, there are cartridges with higher velocities and flatter trajectories. Yes, there are cartridges and loads that are more powerful and hit harder. But it’s worth noting that, even though the cartridge and its original pistol are more than 110 years old and have been superseded by “wonder nines” and “shorty forties,” the .45 ACP and the M1911 pistol are often still the preferred choice of many, whether in commercial circles, law enforcement or the military.

I’ve been paying close attention to the war in Israel and Gaza; watching a lot of footage. Came across some video of Palestinians — probably late teens/early 20s — throwing stones at vehicles in a chaotic protest on a road. This was, I believe, on Saturday, and it wasn’t clear to me whether the footage was real time or from recent protests.

Suddenly, one of the most active stone-throwers pulled up his right leg, his face knotted in a grimace of pain, and he began to hop away on his good leg. His comrades abandoned their pile of rocks and helped him down an incline and out of the frame.

I knew immediately what had happened: The stone-thrower had taken a .22lr round to the ankle or shin.

“Medics in the Gaza Strip have reported treating an influx of protesters who appear to have been deliberately targeted in the ankle by Israeli forces in recent unrest at the volatile boundary of the blockaded Palestinian enclave. At least one person has been killed and dozens more wounded since demonstrations by groups of young men, some of them throwing stones and molotov cocktails, began in mid-September.”

The Guardian being The Guardian, this was presented as a new cruelty inflicted by the Occupation on oppressed Palestinians.

Human rights groups say that such targeting procedures are unlawful as they allow the use of potentially lethal force with no immediate threat to soldiers’ lives.

They did get one paragraph of “balance” into the piece:

In a statement, the IDF said: “Over the past few weeks, the Hamas terror organisation has organised violent riots along the border fence, for purposes of harming Israeli security forces … It should be noted that the IDF resorts to live fire only after exhausting all available options, and only as necessary to handle imminent threat.”

For years, the IDF has been deploying integrally suppressed .22 caliber Ruger 10/22 carbines, originally as a “less lethal” option for riot control. They are also used as a “hush puppy” to take out dogs and lights in raid operations. Because Israel actually adheres to rules of engagement and laws of combat, the Israeli Judge Advocate General tested the effect of fire from the .22lr and reclassified it as a lethal weapon, which restricts its use.

But clearly, it was in the field in the weeks preceding the explosion of violence in Hamas’ Operation Al Aqsa Flood.

The use of a .22 in a sniper role at limited range, especially in urban environments makes a lot of sense. It’s comparatively quiet even unsuppressed, making it difficult for an enemy to determine where fire is coming from. Suppressed, it’s pretty close to silent; only the sonic crack of the bullet is heard. If your target is higher than the ankles, a .22 can be plenty lethal. Ask any emergency room doc.

Chechens deployed .22 snipers against Russian troops in urban combat in the 1990s, using makeshift suppressors made from plastic bottles — a technique depicted in the movie Shooter, based off of Stephen Hunter’s classic thriller Point of Impact. They were taking head shots.

The Russians took heed, and developed a purpose-built .22 sniper rifle, the Kalashnikov SV99:

The .22 LR SV-99 sniper rifle was developed as a precision small-caliber weapon for special forces snipers to silently engage enemy personnel and other targets at ranges up to 100 meters, as well as for training purposes.

For their part, the IDF now has an updated and upgraded Ruger to work with (seen in the top photo):

Countless threads on gun forums have flogged the topic to death and beyond, but it bears keeping in mind that the .22 is more than just a plinker.

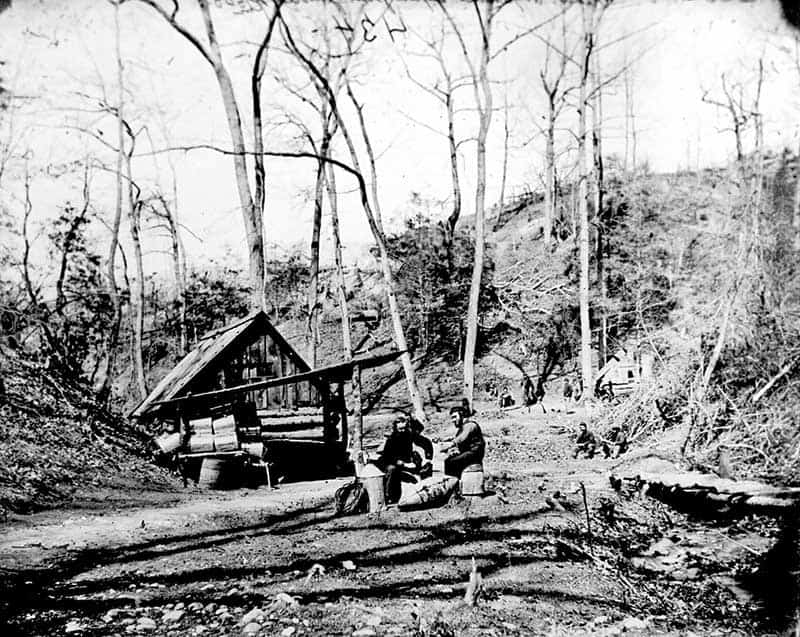

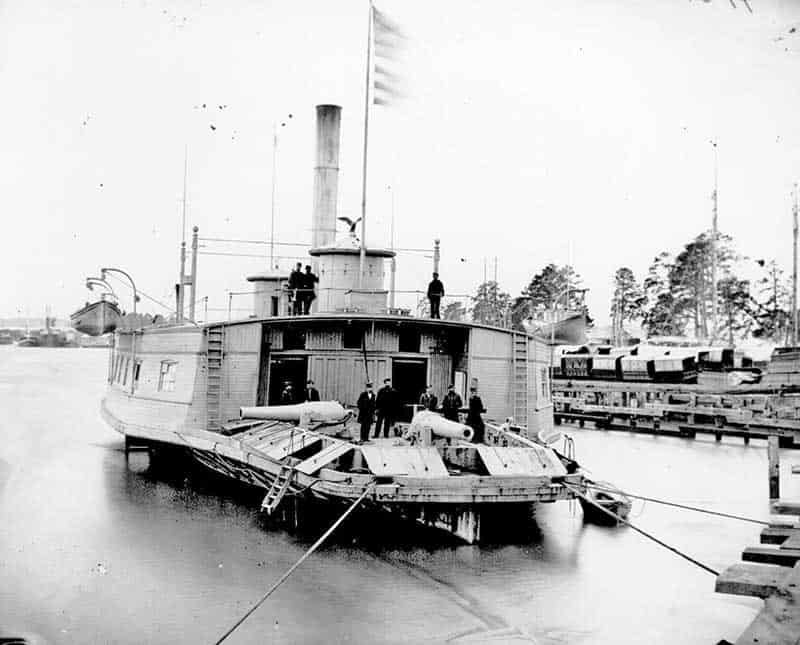

Will’s Civil War-era cannonball (above) originated from the guns of a Union gunboat that once plied the waters of the

Mississippi during the War Between the States.

The Bormann time fuse was a simple powder train arranged underneath something like a clock face. The gunner turned

the fuse with a key and punched through the desired time delay with an awl. The train was supposed to ignite upon firing,

but Bormann fuses suffered a 50 percent failure rate in combat.

America, while still the finest place on earth to live, seems awash in a sundry of tribulations these days. Our moral compass spins faster than the federal government’s debt clock, and verifiable examples of sound judgment in Washington seem skimpier than Paris Hilton’s wardrobe. In addition to these oft-lamented ills, there also seems to be a precipitous and unprecedented decline and dearth of Dads.

Mind you, we’ve got scads of fathers. You can’t swing a dead cat in a public venue without striking a male who has fathered a child. But what we are really growing short on is good old-fashioned, share-an-address-with-his-children Dads. The impetus behind this contemporary pestilence is a complex contagion, but I am blessed with such a Dad, and I am proudly one myself. There are some interesting perks a man can expect from the job.

Mine was a fairly rural upbringing, and we Dabbs men have always prided ourselves on being able woodsmen. My own Dad was out squirrel hunting many years ago when he happened upon what looked like a piece of fruit half buried in the mud. This particular strand of Delta forest was on the wet side of the Mississippi River levee and as such had flooded vigorously every spring since the very beginning of time. Being a typical inquisitive American male, my dad acquired a stick and poked it. The incongruous item turned out to be, much to his surprise, a dud Civil War-era cannonball. As he and I share an unfortunate amount of genetic material, he did exactly what I would have done––he innocently picked it up and carried it home.

Obligatory Disclaimer

Before half the world writes in with colorful observations of what a rank idiot I am, this amusing little tome does indeed have a happy ending. However, never disturb or relocate unexploded ordnance. Your local Law Enforcement officials can put you in contact with the proper agencies for managing such things. The anecdote related herein occurred many years ago. My dad and I are both older and wiser now. The story is related solely for its entertainment value. Testosterone is the most potent poison known to man and many a voyage across the River Styx was indeed launched with the otherwise-innocent question, “I wonder what that does?” Now, back to our tale.

As my dad was walking to his Jeep with the heavy bomb hoisted upon his shoulder, he kept wondering what people would think if it spontaneously detonated. He doubted much would subsequently be discovered of his remains beyond his two smoldering boots. A typical local bait shop discussion might go something like this––“I heard Woody was out squirrel hunting the other day and just blowed slap up. I seem to recall the same thing happened to Billy Ray back in ’73.”

Anyway, he got the thing to the house, aggressively photographed it, and entombed the entire affair in the backyard. On my next free weekend, I made my way home. At the time, I was a mechanical engineer/former Army helicopter pilot grinding his way through medical school. Between the two of us, we had exactly zero useful professional expertise to lend to this unusual undertaking.

At cursory glance, the thing looked like a rusted version of the “Death Star” from the Star Wars movies. It was a typical example of hollow shot fired from the Union gunboats that plied the Mississippi River some nearly 150 years ago during the War Between the States. The iron ball incorporated a Bormann time fuse. This soft metal insert sports something akin to a clock face replete with embossed numbers. Prior to firing, the gunner would punch through the number corresponding to the desired time delay with an awl and load the bomb fuse-forward. Fiery blowby would supposedly ignite the black powder train enclosed therein and detonate the ball the appropriate distance from the gun. Bormann fuses suffered roughly a 50 percent failure rate in combat.

There had been a minor skirmish involving the nearby port town of Friars Point, Mississippi, where Union forces occupied the town and, for reasons lost to history, burned all the churches to the ground. Angry locals fired upon the moored gunboats from the banks of the river, and Union forces peppered the surrounding countryside with random cannonade. The sketchy performance of the Bormann fuse is the reason our example remained intact. Satisfied the fusing system was a simple waterlogged powder train and not some dangerous clockwork contrivance, we advanced to the next stage of our adventure.

Civil War-era gunboats were remarkably complex vessels for their time. Steam-powered and heavily armed, these

leviathans projected Union combat power along the vital Mississippi River. The cannonball depicted in this article was

fired in 1862 from a gunboat similar to this one. Photo courtesy: US National Archives.

Technical Details

We procured a drill press, mounted it atop an old tabletop and headed out to the woods in my folks’ gosh-awful-huge motor home. Behind the RV we pulled a boat trailer loaded solely with a pickle bucket full of sand ridiculously over-secured with heavy nylon tie-down straps. As this is not a particularly atypical sight in the rural Deep South, we aroused little suspicion. Upon arrival at the base of the Mississippi River levee, we ran 300 feet of orange extension cord out into the forest and tied a comparable length of trotline to the drill press handle. We gently removed the sand from the bucket and replaced it with water to keep everything cool, fired up the RV generator and were in business. We had acquired a large rubber gasket upon which to place the rusty cannonball so as to retain it securely within our contraption. I oriented our proposed 1/4-inch breach 90 degrees out from the fuse.

Imagine if you will, the sight of two nominally grown men crouched in trepidation behind a large fallen log next to a motor home, big enough for its own zip code, parked at the base of the Mississippi River levee. Now picture we are also gently tugging a trotline snaking off blindly into the woods. This bizarre sight greeted the game warden as he pulled up alongside us in his big green cop truck.

Law Enforcement Involved

“What you boys up to?” the cop inquired amicably. My dad and I looked at each other, and after a moment’s reflection I said, “Drilling a hole in an old cannonball?” They say honesty is always the best policy.

Now this is one of the countless things I do truly love about the rural Deep South. Had we lived in New York, New Jersey, California, or some similarly storied locale, we’d undoubtedly be immediately clapped in irons, transferred to some special dungeon and labeled a father-and-son homegrown terrorist squadron. However, as we live in God’s country down here in Mississippi (don’t knock it––at least our air is still invisible), this upstanding officer of the law simply said, “Cool. Don’t blow yourselves up.”

We socialized for a bit before he wished us good fortune in our undertaking and drove off. It turns out he was simply concerned we might be trying to camp at the base of the levee, a practice indeed verboten per local statute. Convinced our sojourn was but temporary he departed placated.

The entire process took about 3 hours. We gently tugged on the trotline for a few minutes then unplugged the extension cord to allow everything to cool off while we visited together in safety behind the ample fallen log. We repeated the process as needed while surveilling the ball through a pair of binoculars. When finally we had the hole bored, we allowed another 1/2 hour for cooling and squirted a bit of chilled motor oil into the hole as a spot of insurance.

The cannonball now rests proudly on my mantle, minus the 1/2-pound of quite volatile Yankee black powder it once contained, the very centerpiece of my ever-expanding cool guy-stuff collection. Additionally, Dad and I had an absolute blast together (figuratively, of course) and but for the grace of God got neither killed nor arrested.

Musings

deactivating Civil War-era artillery rounds. It is in the murky spaces between these two ends of the spectrum where profound happiness resides. My own three kids are grown nowadays, and were we to serendipitously trip over a Civil War-era cannonball today, we would indeed leave its recovery to the professionals. However, while we did our share of romping and stomping through the woods together, truth be told, they were not necessarily the greatest beneficiaries of our adventures. This notion has added a depth and richness to my life not to be found in the more civilized pursuits. In the broad field of human accomplishment, little brings quite so much satisfaction, if well executed, as the rewarding job of being a Dad. To my own Dad, thanks. I love you.