Whether munitions drove the development of firearms or firearms drove the development of munitions is one of those chicken and egg questions which keeps coffee table philosophers busy and off the streets. There’s at least one case where we can make the argument that available munitions drove the development of the guns — with the great .577 revolvers produced in the late Victorian Era.

With the exception of the huge Dragoon and Walker Colts, percussion revolvers were typically anemic performers by today’s standards. Even the .44 1860 Army model, perhaps the most widely made and distributed of the Colt percussion revolvers, offered mediocre ballistic performance. The 148 grain conical ball ambling along at a stately 800 fps sounds suspiciously like the .38 Special round-nose factory load which nobody has ever accused of superior man-stopping prowess. Yes, you could kill somebody deader than a hammer with one, but not always right now.

The advent of cartridge revolvers and ammunition didn’t improve matters a great deal. Only the .45 Colt with its 250 gr. bullet at 900 fps was really an adequate performer. Pity the poor English whose concurrent revolver developments offered nothing nearly so useful. The early British cartridge revolvers were chambered for a variety of pathetic little numbers such as the .442 Webley and .450 Adams, most of which tossed along 200-220 gr. bullets at 550-650 fps, underwhelming to say the least. But lackluster performance was no academic question to users of these guns.

The British Empire spanned the globe and was, in many cases, peopled by reluctant participants in this imperial glory. Often as not, these folks did not domesticate well and caused all manner of trouble. Indeed, many offered spirited and effective resistance. Whether on a mission from God to expel the white devils, or simply fortified by locally manufactured pharmaceuticals, the locals often took a lot of killing.

Many a brave officer in the Queen’s service discovered this the hard way after emptying his token side arm to no effect, then getting gigged in the guts or sliced from crown to crotch. Didn’t take much of this for the brighter members of the officer corps to understand more stopping power was in order. Since officers provided their own side arms, those who could afford to procured better ones.

In those days, the only propellant was black powder. The only way to get more power was to use more powder. More powder, in turn required larger

cartridges which, not surprisingly, required larger guns. Out of the quest for effective man-stopping revolvers came some of the most fascinating revolvers ever made, the .577s. Doubtless, designers settled on the .577 caliber because of the familiar Enfield and Snider rifles of the day, figuring that a shortened case suitable to revolvers would do the trick. Regardless, in this instance black powder was the chicken that laid the revolver performance egg.

Cartridge Guns

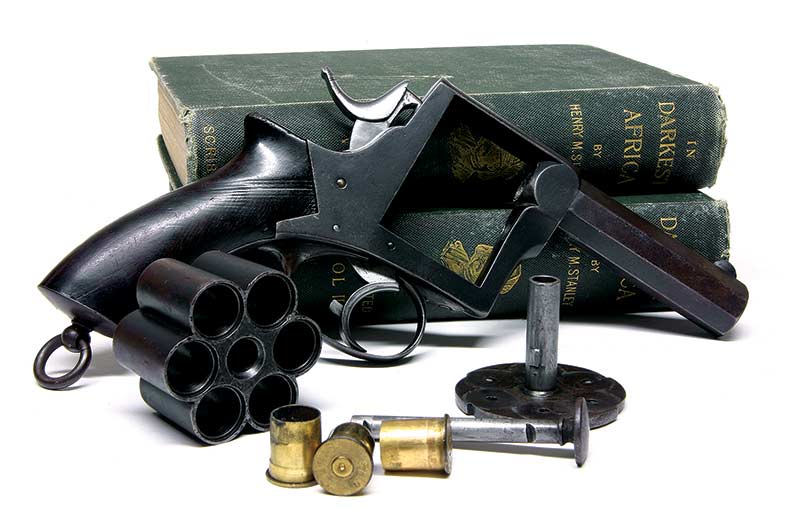

While some .50 and .54 caliber percussion revolvers exist, the literature doesn’t show any .577s. Most known .577s are cartridge guns. Even so, these guns evolved some over their brief history. Early coiled-brass cartridge cases were not terribly dependable and caused function problems. The earliest known solid-frame specimens had complicated cylinder assemblies with backing plates with firing pin holes that fitted between

the case heads and standing breech to assure dependable cycling even in the event of a case failure.

Problem was that reloading was time-consuming and troublesome since you ended up with a handful of parts during the loading operation — cylinder, backing plate and axel, to say nothing of the ammo. Drop any one part and the gun was disabled, a real bummer in a square surrounded by dervishes intent on doing Allah’s work against the infidels.

Improvements in cartridge cases gave rise to the more conventional revolvers made along the lines of the familiar top-break ejector Webleys. In

their final iteration, .577 revolvers used a drawn brass cartridge case heaving a 400 gr. bullet at about 725 fps — by all accounts an effective manstopper. Determining who made the .577 revolvers is a bit tricky. Patent holders and retailers were not always manufacturers. While Webley and Tranter probably produced the earlier solid-frame guns with the backing-plate cylinders, it isn’t clear Webley ever produced any top-break .577s. Some were probably made by Pryse in England, and perhaps by other licensed English makers. Some were manufactured on the continent by August Francotte & Co. of Liege and retailed by outfitters such as the Army and Navy cooperative and various sporting arms makers.

All top-break ejector revolvers I’ve seen have been made on the Pryse patent, regardless of the retailer’s name. Distinguished from the Webley latch system, the Pryse top fastener between barrel extension and receiver consists of a couple of frame-mounted levers which retract a couple of pins from a hole in the barrel extension to permit opening. At least a couple variations in the guns exist with subtle differences in barrel

form, cylinder length and hammer fastener. One thing is for certain, .577 revolvers are extremely rare. Credible estimates suggest fewer than a hundred or so of all stripes were ever made.

Rare or not, vintage .577 revolvers are magnificent arms. The examples we have here are very similar in size and weight to the contemporary Ruger Redhawk. They are perfectly handy and agile in their handling. Recoil, while not insubstantial, is a gentle heave and not bothersome. Sadly, most devout gun cranks will never have a chance to see, let alone shoot one of these marvels. That gave rise to the notion it might be nice to try and build a modern .577.

Ordinary?

In keeping with the character of the original .577s, we (“we” being the Bowen Classic Arms crew, shop dog, et al) wanted a revolver of relatively ordinary size and shape, not some outsized, eight-pound monstrosity with all the grace and handling of an anvil. The basic problem was the cartridge size. The original .577 revolver cartridges were based on shortened .577 Express cases. Since these cases were quite heavily tapered, the original .577 revolvers actually have groove diameters more on the order of .610″-.615″ rather than the usual .585″- .588″ for .577 rifles.

Our only hope of shoe-horning a .577 cartridge of some kind into a revolver lay in dramatically reducing its diameter. Pegging the groove diameter, rather than the bore diameter, at .577, was a good place to start. Even so, if you added in .015″ per side for the brass and a bit of cartridge taper, you’d still have a case with a head diameter of about .610″. For the smallest possible cartridge, the solution was a heeled bullet with a .577 front driving band in a .577″ diameter case, basically a giant .22 Long Rifle cartridge.

So far, so good. But if the groove diameter is .577″, how could the gun shoot well with a heel of only .547″ diameter? More head scratching offered the answer in the form of the Minie ball with its hollow base. In theory, the skirt would obdurate to driving-band diameter and give guidance on each end of the bullet. Since bullets would weigh around 400 grains and be subject to considerable recoil inertia, how to crimp them

firmly was the next question. Heeled bullets can’t be roll crimped because the case mouth is covered by the bullet. Time-tried technology in the form of collet crimping saved the day.

All that remained to complete the basic cartridge design was to procure a suitable parent case. Perusing spec sheets on virtually every known cartridge case turned up nothing useful. Alas, our baby was a bastard. Nothing would do but to make cases. Obviously, drawn brass would have been prohibitively expensive so we turned to the Ballard Rifle & Cartridge Company who, at the time, produced excellent turned brass (now produced by Rocky Mountain Cartridge Company). With the flexibility of CNC machinery, they could make cases of virtually any description. And thus was born the .577 No. 2 revolver cartridge.

Redhawk Rebore

The smallest .577 revolver cartridge still required a substantial gun. At the time, the Ruger Redhawk was the obvious candidate since no other normal revolver had its cylinder and barrel shank diameters. Even then, the .577 No. 2 Revolver cartridge is a tight fit. The chamber walls and webs of the 5-shot cylinder are quite thin, limiting the gun to black powder pressures. Barrels with .565″ bore and .577″ groove diameters are not a size found in nature, so to speak, but we were able to gull our good friend Cliff LaBounty into making a rifling head to rebore the

original Redhawk barrel. In keeping with the vintage nature of the gun, the top strap and barrel were modified to resemble a Smith & Wesson M&P fixed-sight model. Building the gun was simple enough — ammunition proved to be much more troublesome.

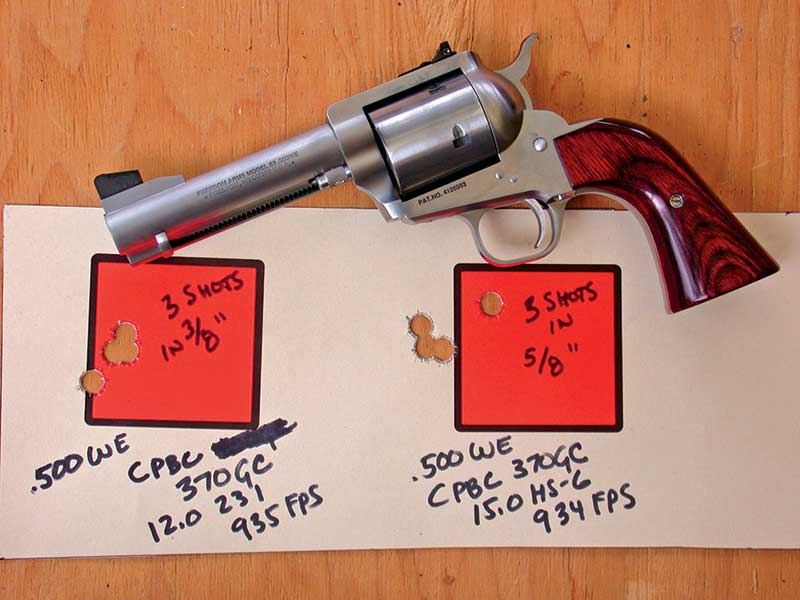

Initial test firing was conducted with standard pistol primers, FFFg powder and a generic black powder lube. Muzzle velocity was about 725 fps but accuracy was disappointing. After 15- 20 rounds, powder and lead fouling were so bad bullets would not stay on the target paper at 20 yards. Consulting with an expert may be unmanly but, in this case, it saved the day.

Mike Venturino and his shooting cohorts had begun to unravel the lost secrets of sustainable black powder accuracy. Mike counseled there are

three basic elements: Use magnum primers, use a drop tube to charge the cases with powder and use SPG lube. Armed with this intelligence, we tried again. Muzzle velocities were still around 725 fps +/- 5 fps. Off-hand groups shrunk to a couple inches and fouling, even after 25-30 rounds, never impaired accuracy or function. Recovered bullets showed the skirts hadexpanded to engage the rifling as hoped.

With good ammo in hand, regulating the sights was a snap. The .577 Redhawk has performed flawlessly to date. Thanks to the weight reduction afforded by .577 chambers and bore, handling is light and quick. Recoil is substantial, much like a heavy .44 Magnum loading but without the bite and piercing report. Scientific penetration tests conducted against a handy fence post demonstrated very modest penetration but a great deal of whack. After two or three solid hits, the post stayed right where it was, unable to escape.

Sadly, the future for newly-made .577 revolvers is pretty bleak. The National Firearms Act of 1934 classifies rifled, breech-loading guns with

bores larger than .5″ as “destructive devices” and levies on the transfer of such arms a $200 tax. Production for resale of destructive devices requires a license costing thousands of dollars a year to maintain.

Big-bore sporting long arms are largely exempt but the BATF would not extend any such sympathy to a .577 revolver and treats the gun exactly the same as a 155MM howitzer. Quite a distinction for a revolver that was state of the art in 1885. Within a few years of their introduction, the .577

revolvers disappeared, usurped by smaller guns made possible by smokeless power — yet another argument in favor of ammunition as chicken and gun as egg.

Two examples of a .32-20 WCF cartridge.

Two examples of a .32-20 WCF cartridge. The .32-20 WCF (left) compared with the .44-40 WCF (center) and .45 Colt (right).

The .32-20 WCF (left) compared with the .44-40 WCF (center) and .45 Colt (right).

An example of a Winchester Model 92 chambered in .32-20 WCF.

An example of a Winchester Model 92 chambered in .32-20 WCF.