When loading them, it was just another box of .45 Colt handloads. I was preparing for a handgun hunt with good buddy Dick Thompson. My mom had died a few months before and Dick graciously invited me out for a handgun hunt in his home state of Idaho.

With mom’s death fresh in my mind the “you only live once attitude” was strong, and I accepted. It was my first trip out west and I’d never met Dick before. I knew we were both huge Elmer Keith fans from our interactions online. So that qualifies him as a great guy, right?

A Proper Load

Since this was to be a handgun only hunt, in Idaho, a proper cast “Keith” bullet was the obvious choice for my handgun hunt. I have a 1970s vintage Lyman four cavity 454424 mold which drops the prettiest bullets weighing in at 260 grains. With its large meplat, or nose, the bullet almost takes on the appearance of a full wadcutter. My chosen load is 20 grains of 2400, sparked by a large pistol primer, in .45 Colt brass from Starline. This load chronographs at just over 1,250 fps.

Load Background

The load comes from a story I read where a Keith fan met Elmer at a gun show. The fan told Keith he uses his advertised load of 18.5 grains of 2400 in his large frame Ruger but has unburned kernels left in his barrel after each shot. Keith pulled him aside and told him, “Bump the charge up to 20.0 grains, it’s what I do,” and winked to him, “That will take care of it.”

Now having a classic, vintage load, with pertinent history behind it, I cast and loaded them in nickeled Starline brass. I filled a plastic 50 round box, smoke gray in color, for the trip. I would be shooting them from my Ruger Bisley Hunter with iron sights sporting a 7.5” barrel.

Success

Luck was with me, and I took a nice cow elk at 121 yards on the second day of the hunt. At the shot the cow elk swung her head, biting at the entrance wound, as if stung by a bee. She was stung all right — with a Lyman 454424 cast slug. She took three wobbly steps and tilted over. Keith’s finest, consisting of 260 grains of WW alloy center punched both lungs and zinged right on through her.

There’s More

Maryland’s opening day of firearms season was a couple weeks later, and I was lucky enough to take a buck and doe with the same outfit and box of shells. The box was quickly developing a track record and I liked it. Five more whitetails were taken from the same box, each taken with one shot.

While it was never my intention to load a special box of shells, it just happened. Shooting a special load learned from a mentor using a humble cast bullet designed by the same, while using an iron-sighted revolver takes me back in time. Using basic equipment doesn’t mean it’s not effective. It just puts the emphasis on the hunter, not the equipment. And as Keith was fond of saying, “you can eat right up to the hole” when shooting a critter with a big bore cast slug.

Afterthoughts

It’s good to know our roots and revisit them from time to time. Experiencing and appreciating what our mentors went through, understanding the hows and whys, and being able to duplicate the way they did things is inspiring. It brings you closer to them as you experience their feats, walking not in their footsteps but beside them.

No Purist Here

As Dick Thompson is fond of saying, “any animal taken with an iron-sighted sixgun is a trophy.” I’ve been fortunate to take a few and experience the rush, pride, and feeling of accomplishment. The challenge is tough, and you must be willing to fail when limiting yourself with a sixgun.

I’m no purist to handgun hunting by any means, not in the sense of Dick Thompson or John Taffin. I still love my rifles and admit to taking them out from time to time. I have the upmost respect and admiration for the purists of the sport, for more times than naught, these guys are going home empty handed.

Dick also says, “I’d rather shoot a grasshopper with a sixgun than a 6X6 bull elk with a rifle.” It’s been more than 45 years since traded in his rifles and he’s still bringing home the meat.

Last Thoughts

While some may see an almost empty box cartridges with about a dozen leftover handloads, for me, it’s a box of memories, adventure, and fulfilled dreams. This box of shells has traveled to Maryland, Pennsylvania, Idaho and West Virginia. Each empty case, with its cratered primer, is a reminder of past experiences. I hope everyone has the chance to load a box of shells as special and lucky as this one has been to me.

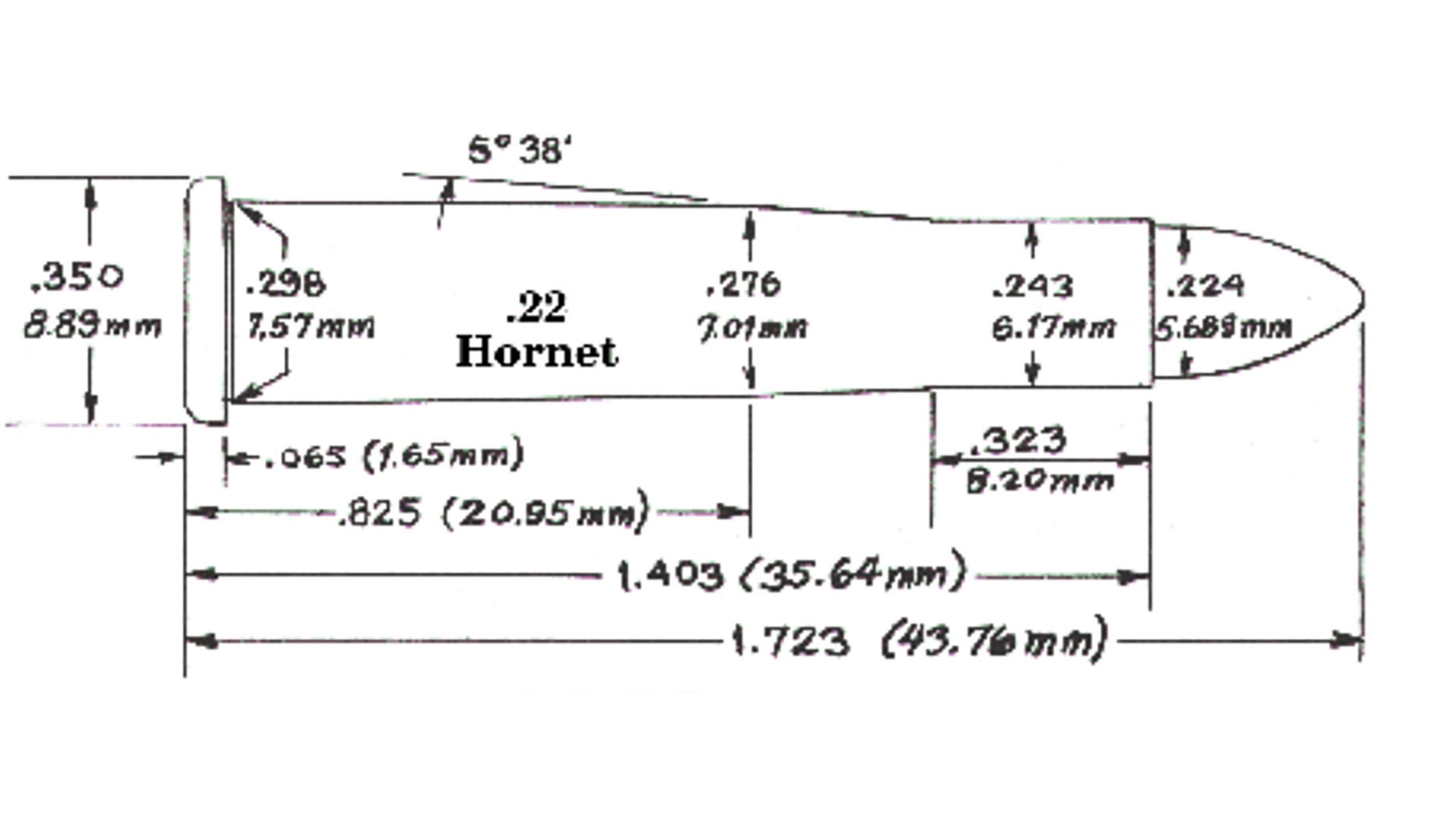

A dimensional schematic of the .22 Hornet cartridge.

A dimensional schematic of the .22 Hornet cartridge.

The standard .22 Hornet on the left compared with the .22 K-Hornet on the right.

The standard .22 Hornet on the left compared with the .22 K-Hornet on the right. A box of Federal 20-grain .17 Hornet.

A box of Federal 20-grain .17 Hornet.