Category: All About Guns

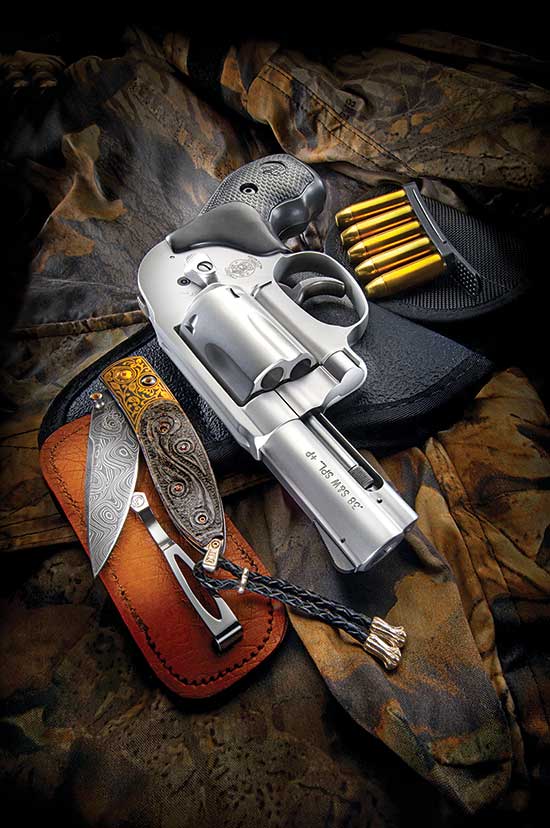

Colt Python at 40yards one handed

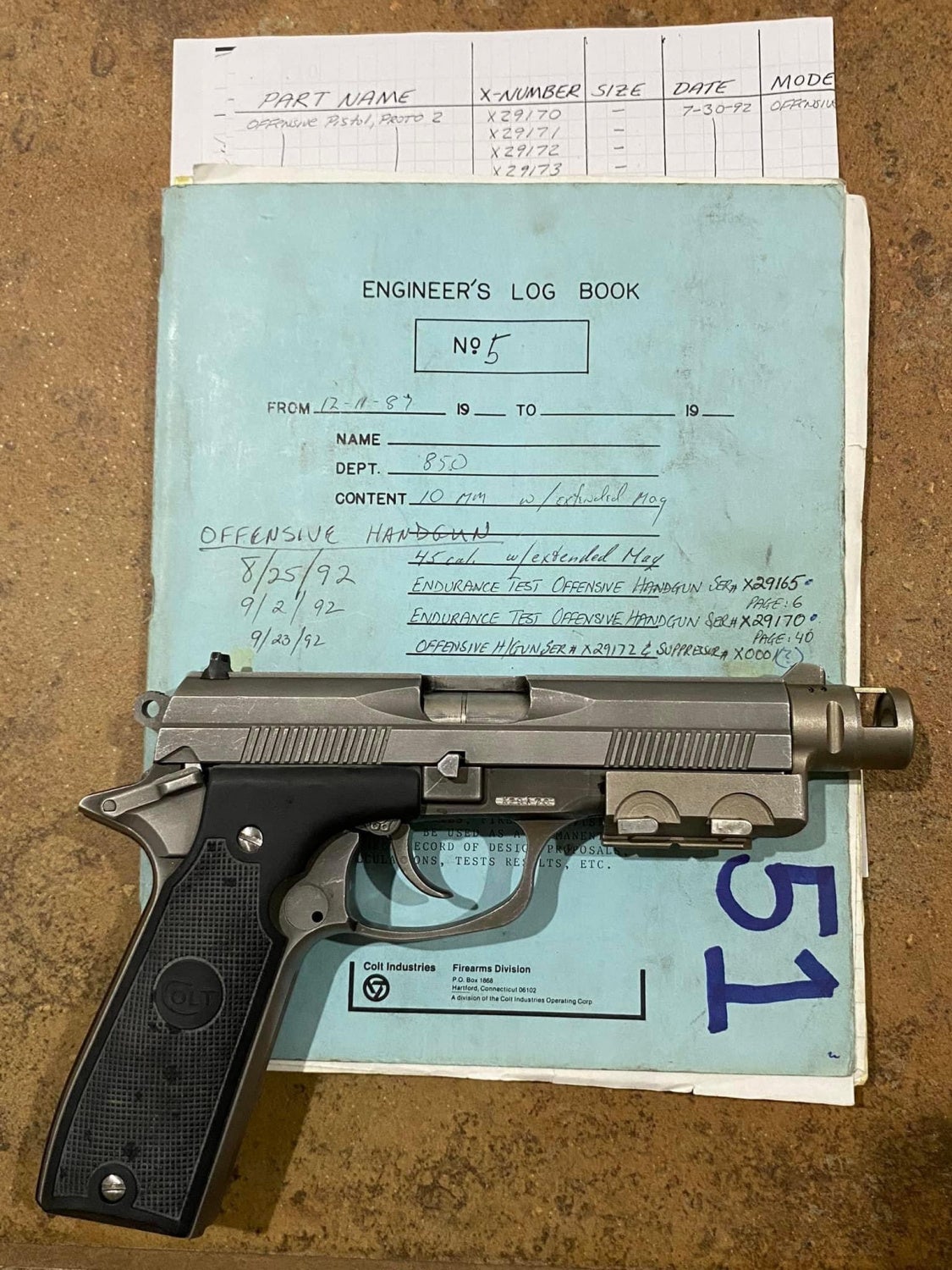

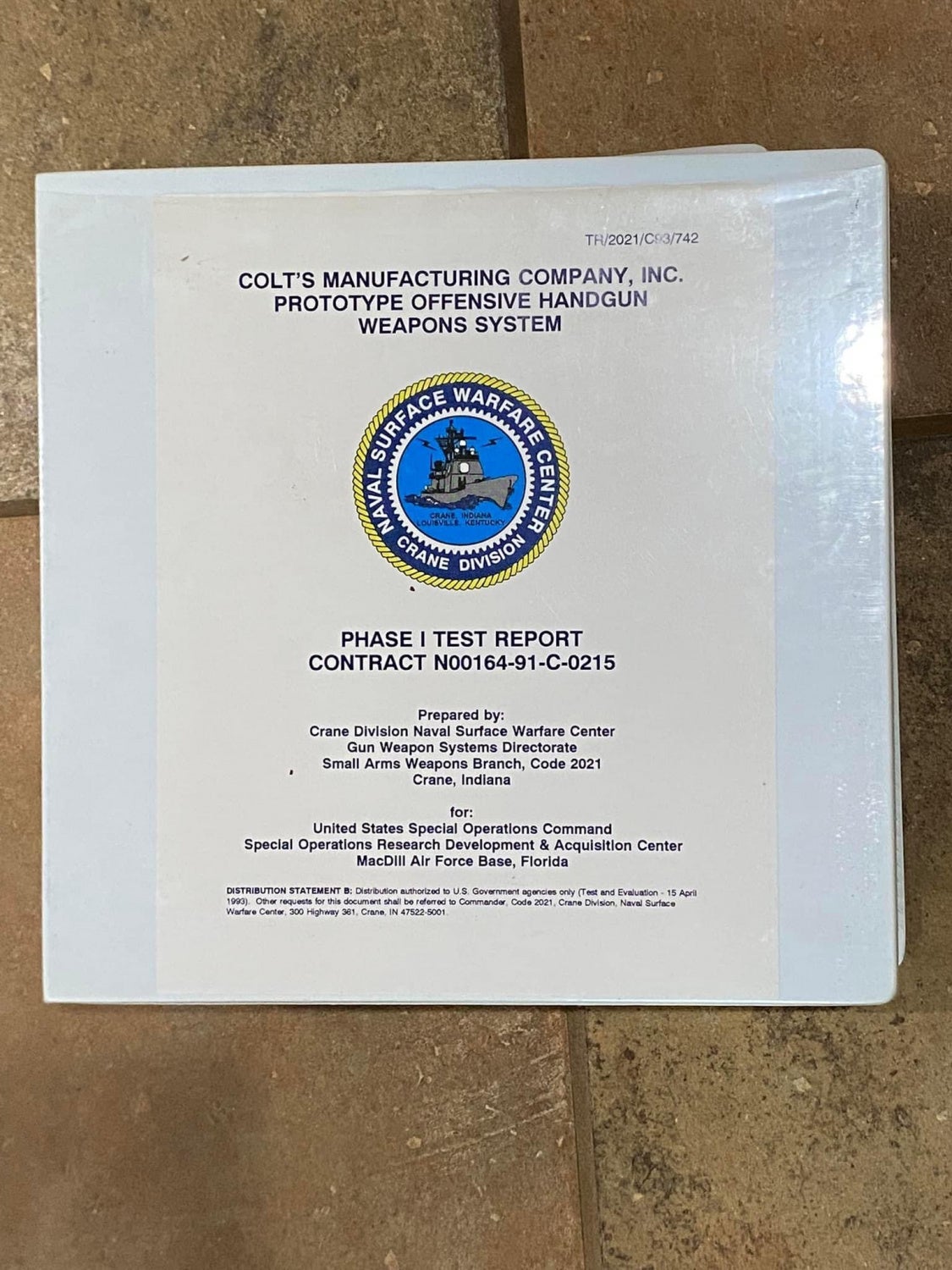

For those who do not know Alex Young, he is an avid aficionado and collector of Colt products and rare AR-15s. I wrote an article on his collection of original Colt roll dies for the AR-15 and M16. Well, Alex has managed to acquire a Colt OHWS. Here are some photos he shared of his Colt OHWS.

OHWS @ TFB:

- Review: H&K MARK23 The Civilian Version MK23 SOCOM

- TFB Collab: H&K Mark 23 Special with 1911 Syndicate

- SILENCER SATURDAY #178: H&K And KAC MK23 – The Most Famous Suppressor Combo?

Back when SOCOM wanted a new Offensive Handgun, the two main competitors were H&K and Colt. H&K ended up winning the contract but what happened to the Colt OHWS? See what Alex wrote about his Colt OHWS.

Colt’s Offensive Hand Gun (OHG) [Colt OHWS]

So this has been something I have been wanting for a while and my first guess was possibly getting one from the Colt archives but was told there weren’t any left.I also sent an email to a few high end dealers that have dealt with larger collections and higher colt employee collections and still nothing.I know 42 [Colt OHWS] serial numbers were made with 30 being shipped to crane in 1992 as tests for the SOCOM’s contract that HK and colt entered. Before that, 2 ‘prototype 1’ guns were made using modified Colt Double eagles with 1 being destroyed. They then moved on to ‘prototype 2’ guns which I was honored enough, thank you to a certain individual putting me in contact with the owner, to get. When I made my offer, I assumed it was for one of the 12 other excess guns colt made. Of those 12, maybe 3-4 still exist. This one was an X marked ‘prototype 2’ version which was the same gun sent to Crane except they had a different finish.The [Colt OHWS] Offensive handguns were a beast of a gun. The contract stated that it had to be at least 10 rounds of 45 capable of shooting 45 +P, have a laser aiming module, quick detach suppressor, double/single action, decocker, slide lock for suppressed single shot use and then weight and dimension requirements.Colt management at the time was suffering a huge loss due to the failed Am2000 design they bought from Knight’s and didn’t have 2 cents to rub together. The pistol I bought was from of the design engineers so most information came from him as well the Crane report I will mention later.With the overwhelming debt Colt had, they saw an opportunity to use the Socom contract money to do more research on some current models they were having issues with. Management made the engineers use the double eagle trigger action and the rotating barrel of the AM2000 both of which the engineers said was a horrible idea, but management wanted the time and money to find a way to fix these 2 systems.So the engineers made this from what they were allowed to do by management.Colt even went to S-Tron for the laser aiming module (LAM) which they ended up going bankrupt during phase one testing and could not supply colt with any parts of assistance during testing. Reps were not even sent to Crane to assist in their own product. Almost every unit was deemed worthless at the end of testing due to cheap materials and several didn’t work right out of the gate when the crane soldiers were unboxing them upon delivery.The muzzle device did have some Eugene Stoner inspiration. When he was accompanying Reed to the back vaults of colt getting anything of value to get reimbursed, the engineer introduced himself to Eugene and asked him about an issue they were having with attaching a suppressor mount to a rotating barrel and he sketched something up really quick and the design was based upon that. Again, rotating barrel, not a great idea but managements idea.The main issue with this design was that the barrels cracked around the 20k-23k range. The barrels were machined incorrectly from their suppliers and have a sharp face instead of a slanted face to soften the blow so they were cracking right at the sharp face. There were other smaller issues like misc springs and small parts breaking but those are simple fixes. The guns also averaged 6” unsupsressed and 11” suppressed, again due to a managements decision for a rotating barrel.The magazines that were tested in the prototype phase were adapted off the shelf 11 round magazines that colt later made themselves some 10rd mags for the actual trials.The colt submission was a last minute design and by the time everything was done and loaded and the drive was made, they had made it to crane within 3 hours of the deadline so they cut it pretty close!So with this [Colt OHWS] specifically, the engineer was able to save the original engineers log book from the trash for this specific gun documenting all rounds and issues this gun had over its 23k round life. The main things were the barrel cracking at around 10k round and ended breaking at 21,500 and being replaced. Also a few other small parts at the 21k-23k range so if the barrels were machined correctly, probably last a lot longer than that. All of this was with 100% 45+P ammo so pretty good. I also got an original S-Tron manual, pictures of the colt offensive handgun team, crane test team and a copy of the X prefix book showing this serial number.Also from a different collection just this last week I got the original Crane report that was sent to command in FL for colts pistols [Colt OHWS] showing all serial numbers, testing factualities, pictures of guns, and defects. It also goes over issues they saw and what needed fixed in phase 2 that never ended up happening.

So, excuse my poor article writing and such but hope this was informative and brought some light to an otherwise dark program.

Photo by Alex Young

Photo by Alex Young

Photo by Alex Young

Photo by Alex Young

Photo by Alex Young

The below is an excerpt from the 1978 book, Olympic Shooting, written by Col. Jim Crossman and published by the NRA.

The National Skeet Shooting Association

By Colonel Jim Crossman

Unlike most shooting events, skeet is of fairly recent origin and it is easily possible to trace the history of this shotgun game and its parent organization, the National Skeet Shooting Association.

Unable to get in enough grouse hunting to satisfy themselves, and not enthusiastic about trapshooting because it did not simulate bird shooting conditions, a group of New England hunters experimented with traps and clay birds until they worked out a game that seemed practical as field training, was fun to shoot, and was not too difficult to set up.

One of the group, W. H. Foster, became associated with a publishing firm which put out two very popular outdoor magazines, the five-cent Hunting and Fishing and the expensive 10-cent National Sportsman. Foster’s articles on the subject of the new game, first called “clock shooting,” aroused so much interest among readers that it was promoted as a new shooting sport. In 1925 complete rules and instructions were published. At the same time a prize was offered for the best name. “Skeet” was the name selected, and a good name it was, so that it remains skeet to this day.

Skeet grew rapidly up to World War II. The designers of skeet had done their work well in working up a game for teaching people to hit moving targets. So, skeet went to war. With the sudden urgent necessity of training aerial gunners as well as anti-aircraft gunners how to hit a moving airplane, skeet was seized upon as an important step in teaching swing and lead on a flying target. Many skeet shooters of the time found themselves in uniform, teaching skeet every day. Thousands of young men were exposed to shotgun shooting for the first time during this training, which was partly responsible for the great increase in shooting and hunting after the war.

The Hunting and Fishing and National Sportsman magazines had a proprietary interest in skeet, since they had originally promoted it and had devoted much money and magazine space to it. Thus, while there was a National Skeet Shooting Association in the 1930s, its officers read like the masthead of the magazines. But with the war and the lack of ammunition, skeet shooting for civilians practically stopped. The two magazines went out of business and the association became inactive.

With the end of the war, the National Rifle Association of America undertook to revive the skeet association. The NRA lent the embryo organization money and provided it office space. E. F. “Tod” Sloan was appointed manager of the organization. Sloan, although a rifle shooter, had long experience in competitive shooting and in promoting civilian shooting, his most recent military assignment having been as the Army’s Director of Civilian Marksmanship.

In 1952, after the organization was on its feet, Sloan resigned and the NRA bowed out, with Sloan taking a position as NRA field representative in the West, a position he filled with distinction. The skeet organization was turned over to the members and their elected officials. For many years, NSSA conducted its championships at various locations across the country, including the International Gun Club at San Antonio, Texas. This was a privately owned beautiful big layout, with all sorts of shotgun shooting taking place and with much room for expansion. The NRA conducted tryouts for its shotgun squads for the 1967 World Moving Target Championships and the 1968 Olympics at this club. In recent years the club ran into financial difficulties and NSSA bought it in 1974 and has moved its headquarters to that location.

Skeet is relatively new to the Olympic Games, although it has been part of the UIT program for many years. Skeet first appeared in the Olympic program in 1968 and it carried on into 1972 and 1976, although in a form barely recognizable by American shooters.

U.S. skeet has gotten away from some of the basic principles of the original game and a few major changes in rules have made it a much easier game. International skeet, on the other hand, is more difficult than the original sport, so there is now considerable difference between skeet as shot in the United States and as shot in international competition. There has been much discussion about making U.S. skeet tougher, both to reduce the large number of perfect tie scores and to improve international chances, but a vote by the directors in 1968 said no to the attempt to make U.S. skeet more difficult.

For those shooters who are interested in international skeet, the NSSA has established a separate International Division and there are a few events at the national championship shot under the international rules. The NSSA, not a member of the UIT, now works closely with the National Rifle Association in promoting international skeet. [Note: USA Shooting took the reins for international and Olympic skeet development and competition in the United States in 1994.]

If lightweight, maneuverable, and easy-to-handle firearms are interesting to you, then you better start paying attention to KelTec.

At SHOT Show 2023, KelTec showed off a miniature bullpup KSG chambered in 410 that is lightweight with virtually no recoil. They also unveiled the new R50 5.7 Carbine which is built upon their famed P50 pistol but features a full-length 16-inch barrel and folding stock.

R50 5.7 Carbine

Very similar to the tried and true KelTec P50 pistol, the R50 rifle features a 16-inch threaded barrel and folding stock to make quite an effective and compact package.

Due to the design, there is no need for a buffer tube and the R50 still ends up with an overall length shorter than AR pistols or other AR-style SBRs. It features a Picatinny rail on the top of the receiver ready for any modern optics and runs off of 50-round standard capacity magazines for the FN P90.

The top of the receiver pops open to reload the R50, and then clamps back down tight. While reloads take a little longer than with some other platforms, they won’t be needed as often due to the 50-round capacity.

Also, 5.7x28mm fired from a 16-inch barrel is zipping through the air fast! This is a pretty sweet setup if you ask me.

Featuring a folding stock that can rotate in either direction, the R50 is one compact package. The stock felt fairly comfortable and was quick to deploy. Utilizing grooves in the side of the receiver, the stock stows away well.

The R50 5.7 Carbine should be available somewhere between July-August and will have a posted MSRP of around $825.

Specs

- CALIBER: 5.7 x 28mm

- WEIGHT UNLOADED: 3.48lbs

- MAGAZINE CAPACITY: 50

- OVERALL LENGTH: 30.5″

- LENGTH COLLAPSED: 21.5″

- BARREL LENGTH: 16.1″

- TWIST” 1:7″

- TRIGGER PULL: 5lbs

KSG410 Shotgun

KelTec was happy to show off its newest shotgun, the KSG410. Rept told us that it is the “lightest, thinnest and shortest 410 bullpup shotgun in the world.”

Maintaining the dual tubes like the traditional KSG, the KSG410 is able to hold 5 + 5 + 1 three-inch shells. It also features a carry handle grip with a fiber-optic sighting system similar to the KS7.

Specifications:

- CALIBER: .410 Bore

- WEIGHT UNLOADED: 5.4lbs

- MAGAZINE CAPACITY: 5 + 5 + 1 (3″ shells)

- OVERALL LENGTH: 26.1″

- BARREL LENGTH: 18.5″

- TRIGGER PULL: 5lbs

- LENGTH OF PULL: 13″

Coming in at just only 1.7 inches wide, the KSG410 is a very slim platform. Especially so, due to the fact that it incorporates dual tubes for larger shell capacity.

It also weighs in at a mere 5.4 pounds so it can be easily managed by nearly all age groups. While 410 is still a competent round, the KSG410 was built to fire these rounds while being “virtually recoilless by any pump-action shotgun standards.”

The KSG410 should be available around Q3 and will have an MSRP of about $495. To read more about the KelTec KSG410, click HERE.

—————————————————————————————Buck Rodgers would like this one! Grumpy

IWI Masada

1929 Colt Police Positive Special

The mighty X-frame revolvers and the gorgeous handguns of their Performance Center notwithstanding, the single most popular handgun Smith & Wesson makes today is the J-frame revolver. Now in its 60th year, it’s probably our most ubiquitous “everyday” handgun. While the classic service revolver has largely been relegated to the police museum, the J-frame outnumbers even baby Glocks in the backup holsters of America’s police.

Many concealed carry instructors find it the most common gun for newbie students to bring to class. When American Handgunner polled its staff writers on their carry guns a couple of years ago, the one most constant factor was one or another permutation of the J-frame in almost everyone’s “carry rotation.”

They’re handy, they’re simple, and they’re dead-nuts reliable. Their slim barrels and rounded butts make concealment easier in pocket holsters, ankle holsters, belly bands and even inside the waistband holsters. You can get them as light as 10.5 ounces (the Model 317 Titanium 8-shot .22 LR) and 12 ounces (the Model 340 PD Scandium .357 Magnum 5-shot); and with barrel lengths from 17/8″ (nominally 2″, and still the most popular), to 5″ (the Model 60 .357 variant introduced in 2005). Calibers over the years have included .22 LR, .22 Magnum, .32 Long, .32 H&R Magnum, .327, .38 S&W, .38 Special, .357 Mag, 9mm and even the short-lived .356 TSW. Of them all, though — from the first Chief Special of 60 years ago, to the single best-seller today, the Model 642 — their most enduring and most popular format has been that of a 5-shot, snub-nosed .38 Special.

A Brief History

The year was 1949. Carl Hellstrom had taken over as CEO of S&W, and didn’t like the fact that arch-rival Colt had possessed a monopoly on small frame, short barrel .38 Special revolvers since introducing the Detective Special circa 1927. He ordered his engineers to beef up the small I-frame revolver, hitherto the core of S&W’s .22 Kit Gun and small .32 and .38 S&W pocket revolvers, so it could be manufactured in .38 Special. This required lengthening the frame and the cylinder. The new revolver was introduced at the 1950 national conference of the International Association of Chiefs of Police in Colorado Springs, and was dubbed the Chief Special. (Or “Chiefs Special” according to S&W historian Roy Jinks, or “Chief’s Special” according to the authoritative Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson by Jim Supica and Richard Nahas). The little revolver was an instant hit, and the die was cast. The new paradigm of the hideout revolver would, forever after, be a 5-shot .38 Special on a stretched .32-size frame.

There are three primary configurations of J-frame, and that was set in stone within the first five years of the line’s existence. In 1952, at the request of the already famous Col. Rex Applegate, Hellstrom blended the Chiefs Special platform with the enclosed hammer and grip safety features of the top-break New Departure Safety Hammerless, an 1880s design. Because 1952 marked S&W’s hundredth year in business, they called the new “hammerless” the Centennial. Then, 1955 would see a third option. Reacting to Colt’s introduction of an optional bolt-on hammer shroud for their small frame revolvers circa 1950, S&W designers created a Chief with a built-in hammer shroud and dubbed it the Bodyguard. The tip of its specially-shaped hammer created a “cocking button” that allowed easy-trigger single action firing, but retained the snag-free nature of the Centennial.

The J-frame would be a test bed for S&W innovation. In 1952, the first aluminum-framed Airweight to leave the production line was a Chief’s Special, a variant that would later become known as the Model 37 when S&W went to numerical designations in 1957. So was the first all stainless steel revolver by S&W (or anyone else), the Model 60, introduced in 1965. The first Titanium Smith & Wesson was yet another J-frame, the .22 caliber Model 317 of 1997. When Scandium first made its way into Smith & Wessons at the turn of the 21st Century, those were J-frames, too.

Picking Your Format

Shooting paradigms change, and tastes of shooters change with them. The Chief and the Bodyguard have been in continuous production in one form or another since their introduction. The Chief, of course, is a traditional look double/single action revolver with exposed, spurred hammer, though it has been produced for NYPD and others with the hammer “bobbed.” The Bodyguard looked different enough that some purists thought it ugly, and from the beginning Smith fans nicknamed it “the humpback,” a term you’ll see at the excellent S&W Forum (www.smith-wessonforum.com) to this day.

The Centennial was a different kettle of fish, and quickly found itself on the hind teat of J-frame sales. In the mid-20th Century, many shooters preferred to cock their wheel-guns to single action, and considered double action shooting to be something they would do only in a rare, fast-breaking emergency. The grip-safety put them off, too. The Bodyguard was just as snag-proof coming out of a pocket or shoulder holster, so what the heck was the point of the Centennial? Circa 1974, S&W put the Centennial out of its sales misery and out of the catalog.

Somewhere in the background, one could almost hear the choir singing, “You don’t know what you got, ‘til it’s gone.” By the mid-70s, people were growing savvy to the fact that if you were carrying the gun for those “rare, fast-breaking emergencies,” that’s what you should be practicing for by shooting it that way all the time, so who needed single action? Suddenly, demand for Centennials on the used gun market skyrocketed, and so did their prices.

Along about then, folks were figuring out that because the “horn” on the backstrap rose higher on the frame of a Centennial than other J-frames, the shooter could get the firing hand higher on the gun, lowering the bore axis and significantly reducing muzzle rise. A clamor arose for the reintroduction of the Centennial. Circa 1988, I was at a conclave of writers hosted at the S&W factory by then-CEO Steve Melvin. He told us he wanted to reintroduce the Centennial, this time without the superfluous grip safety. We endorsed it heartily, to a man, and the “hammerless” was soon back in the line as the Model 640 — a stainless .38 Special in all steel in its first iteration, with traditional 17/8″ barrel, sans grip safety, and marked +P+ on the frame. It sold like the proverbial hotcakes. Fifteen years after its discontinuance, the Centennial’s time had finally come in the marketplace.

Today, S&W’s head of revolver production, Jim Unger, says the Centennial is the strongest seller in the entire line. The Chief Special with traditional spurred hammer, is second. He tells me the Bodyguard is experiencing something of a resurgence in popularity and biting close at the heels of the Chief for second place honors. The single best-selling handgun in the whole S&W catalog is the Model 642. That’s the classic-look Centennial in .38 Special, with stainless barrel and cylinder and “stainless-look” aluminum Airweight frame. Weight is just under a pound, unloaded. In sales by caliber, according to Jim, the old standby .38 Special remains number one, with .357 Mag second and the .22 rimfires third. In 2009, the company responded to dealer demand and began offering the J-frame chambered as a six-shot .327, which of course will also fire .32 H&R Mag and .32 S&W Long.

The choice between Chief, Bodyguard and Centennial is among the first of many branched paths you take when you enter the vast domain of S&W J-frame options. Each has pros and cons. It goes kinda like this.

Details

Good news: Easy to cock if that’s how you like to shoot, particularly with something like the longer barrel 317 .22 carried as a trail gun. Potential snag of hammer can be overcome by drawing with thumb on hammer, turning your thumb into a “human hammer shroud.” Keeping finger off trigger and thumbing hammer back just enough to drop the bolt and free-up the cylinder allows a cylinder rotation check to make sure there are no high primers that are going to jam the gun in firing. If something does make the cylinder bind, the Chief gives you the most leverage of the three designs to force the hammer back and get a shot off.

Bad news: Too-small, too-smooth, old-style stocks (or too weak a grasp) allow the gun to roll up in the shooter’s hand. In rapid fire, that can quickly allow the spurred hammer to contact the web of the hand, which will block its motion and prevent the gun from firing. The hammer spur, even the reduced profile on the currently produced models, is still “shaped like a fish hook” as NYPD Inspector and firearms authority Paul B. Weston used to say, and can snag on something and stall your draw in an emergency. If fired through a coat pocket, it is possible for a fold of pocket lining to get caught between the face of the hammer and the frame, jamming the gun and preventing firing.

Bodyguard

Good news: That ugly hump of the hammer shroud acts as a “catch point” against the web of the hand to make it much less likely that the gun will roll upward in your grasp upon recoil sufficiently to impair your ability to fire the gun. It is totally snag free. You can thumb the hammer back for an easy single action pull for a “precision shot” if need be. You can safely perform cylinder rotation checks, as with a Chief.

Bad news: Dust collects inside the hammer shroud, and you’ll need to take a pipe cleaner or Q-tip to it regularly, particularly if you carry in the pocket. With just the tiny stub of the cocking button to work with, un-cocking the hammer can become a nightmare, and that problem increases exponentially when you have to do so with hands that are covered with sweat, shaking from adrenaline, and numb from fight-or-flight-induced vasoconstriction, or from winter cold.

Centennial

Good news: It has the best control in a J-frame because you can get your hand so high and the bore axis so low. Even with the super-light .357 Mags, which come back into the hand brutally, you can keep all shots on target fast because the muzzle doesn’t rise as much. You will stop hurting when you stop shooting. This won’t be true for the bad guy on the other side of your gunfire. You have absolute freedom from snag in any kind of draw.

Bad news: There is no safe way to do a cylinder rotation check on the fully loaded Centennial, because the trigger will have to be pulled slightly back for the bolt to release. We’ve tried all sorts of “stick another finger behind the trigger” and all that, and it’s just too awkward. With the Centennial, you have to have your double action trigger pull skills down pat, and you have to know the chambers are clean and won’t keep a fresh cartridge from seating fully, and you have to inspect and know your carry rounds have no high primers.

Shooting The J-Frame

By the time your J-frame reaches .38 Special caliber, the recoil starts getting mean with serious ammunition. By the time it hits .357 Magnum with full power loads in the 12-ounce variation, it turns into something close to a torture device. It wants to move in your hand, and your hand just wants it to move away. A few tips from an adult lifetime of teaching folks to shoot these things might be in order about now.

Hold the gun hard. Whomever it was that said “hold your gun with 40-percent strength in your dominant hand, and 60-percent strength in your support hand, and above all, just relax” had never fired a light J-frame with +P or, God help us, full-power .357 Magnum. The harder you hold it, the less it will move upon recoil. The harder you hold it, the less it can come back and whack the web of your hand with the upper part of its backstrap, or your middle finger with the back of its trigger guard. And the harder you hold it, the less the ten-ounce gun can move off point of aim as you exert a ten-pound trigger pull upon it, suddenly and swiftly.

Unless you have extra-long stocks, which kinda get in the way of the whole hideout gun concept in the first place, curl your little finger tightly under the butt. This makes the other fingers sympathetically stronger, and also creates a block against the gun rolling backward and muzzle upward/butt downward in your grasp upon recoil.

S&W has equipped these guns with at least four different cylinder latch configurations over the years. The one least likely to slice your thumb firing right-handed, and will still allow you to open the cylinder quickly, is the current production version, which is sort of a checkered semi-oval shape.

From the beginning, these guns were cursed with tiny .10″ wide front sights, with correspondingly tight rear sight notches, which were almost useless under less than perfect conditions. They’ve gotten better. The replacement fixed sights from Bill Laughridge at Cylinder & Slide Shop are so good that S&W put them on their larger framed Night Guard snubbies. Dave Lauck at D&L Sports came out with a great retrofit that I have on my 11-ounce Model 342 Titanium Centennial, and just love. Hamilton Bowen of Bowen Classic Arms also does a sterling job with his sights. At Smith, the humongous Tritium XS 24/7 sight with correspondingly large rear U-notch gives a superb combination of speed and accuracy. It’s found only on the Model 340 M&P .357 at this time, and is the primary reason I bought that gun and carry it most of the time as a backup.

Consider Crimson Trace LaserGrips. I have them on multiple J-frames. Particularly on the older models with less-perfect sights, they make huge sense. They’re now available as S&W factory options on many J-frame models.

Latest Developments

One shortcoming of the J-frame snub has always been incomplete ejection. Between the 17/8″ barrel and the traditional ejector rod lug, the ejector rod became necessarily stubby and just didn’t have enough stroke. That has been changed of late, and you can thank American Handgunner editor Roy Huntington, a long-time J-frame fan.

Roy explains, “After a comprehensive shoot at Gunsite with S&W’s Paul Pluff and about 30 J-frames of all flavors, I came away with the firm conviction a slightly longer barrel and ejector rod would be more efficient. I chatted at length with Jim Unger at S&W, and he was very open to improvement ideas. Some months later during a meeting at a trade show, Jim said, ‘Wait until you see what we have out later. I’m sure you’ll like what you see!’ It turns out the newest offering in the J-frame line-up does indeed have slightly longer barrels and ejector rods. I’m impressed Jim listened to what we learned at the shoot at Gunsite. The guns should offer more reliable ejection and a bit more sight radius to make hitting easier. On a side note, I was not surprised to see many of us regularly hitting 100 yard steel silhouettes, even with the 2″ guns. These guns are indeed accurate in the right hands, solidifying my trust in the J-frame.”

Having shot several of the new 2.5″ J-frames, I can tell you Roy’s predictions have come true. The 5/8″ difference in sight radius becomes significant in a gun as short overall as the J-frame snub, and probably most important, ejection of spent casings is much more positive. Plucking partially ejected brass out of the chambers does not make for a “speed reload,” it makes for a “slow reload.” This longer rod definitely helps. Barrel profile is dramatically changed, of course, but Jim Unger tells me that DeSantis and Galco are already on line with holsters to fit the new-length “J,” with more to come from other makers. The 21/2″ guns are available in Airweight Chief Model 637, Airweight Bodyguard 638 and Airweight Centennial 642 configurations. All weigh 16 ounces with the slight added barrel heft, and all carry a suggested retail of $640 with standard “rubber” grips, and $924 with Crimson Trace LaserGrips.

Also available from the list are J-frames with an integral recoil reduction port ahead of the muzzle. These are in the Pro Series, S&W’s line of upscaled handguns designed and engineered in the Performance Center but built in main-line mass production to reduce cost to the buying public. Upward jets of expanding gases at the instant of the shot do indeed help keep the muzzle down, but they also pose a danger of burning powder debris striking the shooter’s eyes and face if fired from a close-to-the-body retention position. Tailor your choice to your particular defensive manual of arms. My own favorite in the crop is the Pro Series Model 60 .357 with flat-sided 3″ barrel.

And More To Come

By the time you read this, S&W will have introduced their 2010 new products list, in which the J-frame line is richly represented. We will see the return of the all-steel .22 Kit Gun, the stainless Model 63, now in a 3″ barrel/8-shot cylinder format.

And, speaking of .22 Kit Guns, remember the Model 43 Airweight Kit Gun in .22 LR, and the Model 51 Kit Gun in .22 Magnum? Well, 2010 will see the Models 43C and 351C. The “C” stands for Centennial, and we’re talking about eleven-ounce “hammerless” .22s to duplicate the feel of today’s most popular pocket revolver. The 43C will hold eight .22 Long Rifles, and the 351C, seven .22 Magnum rounds. Sights will resemble the excellent high-visibility models seen on the M&P 340 in .357.

The J-frame Smith & Wesson’s 60 year history encompasses both evolution and revolution — and that history is far from over.