Category: All About Guns

Have Guns Got Better Over Time?!

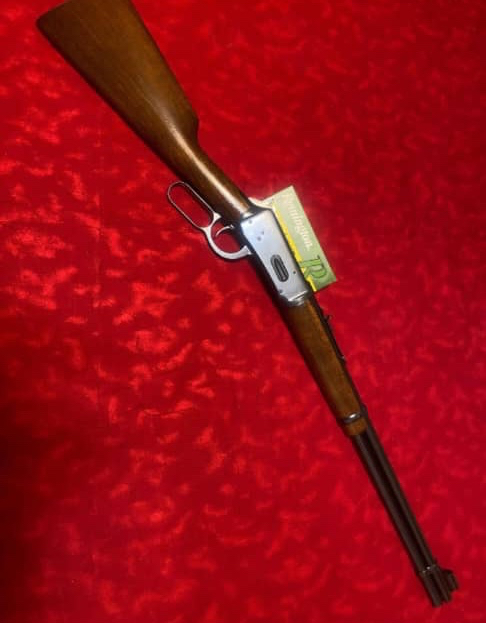

Henry Homesteader

Note: This was one of Skeeters early articles for Shooting Times and he had not starting using his nickname of “Skeeter” in his byline.

In the uncomplicated days before the Great Misunderstanding of December 7, 1941, no one I knew had a .44 Special because no one I new could afford to by a gun. Although plenty of Smith & Wesson’s New Century (Triplelock), 1917 Hand Ejector, and 1926 Military models must have been around somewhere, I couldn’t find ’em.

Handgunnery in my Dust Bowl social circle was carried on with creaky old Colt single actions and modestly priced Iver Johnson Owlheads in .32 caliber . Forward-thinking pistoleros, a lot of them Texas Rangers, favored 1911 Colt .45 autos – mostly marked “United States Property,” relics of the Argonne Forest or some such.

Colt catalogs of the period mentioned that New Service, New Service Target, and Single Action Army models were in the .44 Special dimension, but the only ones I ever located reposed in the displays of affluent postwar collectors.

It was a situation to drive a man to the jug, and the inflated prices of a gunless, wartime market did nothing to help. Every year or two, if you were lucky, you might glimpse a classified ad offering a .44 Special revolver, at prices that would bankrupt a bricklayer. The postwar boom helped little. Years went by before any gunmaker got around to dishing up a good forty-four.

Through this whole mess, my appetites were honed by a dedicated group of individualists who called themselves “The .44 Associates.” At the time I thought these aficionados of the .44 Special rather smug. They already had their guns, and interchanged loading information and jokes about .357 shooters in a regular newsletter. My simmering envy of the .44 Associates was finally boiled over by the excellent magazine articles of Gordon Boser and the flamboyant Elmer Keith.

I sold my .38 Special. I sold my saddle. I cashed in my War Bonds and quit smoking. With bulging pockets, I walked to Polley’s Gunshop in Amarillo and paid my friend, Tex Crossett, $125 for a clean, tight .38-40 Colt single action. This was in the late ‘forties, and the thumbusters’ prices were still held high by the Colt factory’s refusal to tool up and produce them for their postwar fans.

Trying not to think of my stripped bank account, I shipped the old Colt to Christy Gun Works, who installed a matched .44 Special barrel and cylinder of their own manufacture. California’s old King Gunsight Company added a lowslung adjustable rear sight and a mirrored, beaded, ramp front. Somebody else did me a trigger job, and bright blued the whole package. Panting for breath, I plunked down 20 bucks for a pair of one-piece ivory grips, $20 more for bullet molds, sizers, and loading dies, and started a charge account to get empty cases. It had taken ten years, but I had my .44 Special.

Any handgunner who got his start less than ten years ago may well wonder what all the fretting was about. The .44 Magnum completes its first decade this year. A longer, stronger version of the .44 Special, it eclipses the performance of the Special even more than that cartridge overshadowed its own father, the .44 Russian. All fire bullets of the same diameter, of approximately the same weight, and revolvers of the newer calibrations will efficiently handle the older factory loadings.

The .44 S. & W. Special is simply a longer version of the .44 Russian, throwing the same bullet at the same velocity. It is inherently more accurate than any other pistol cartridge that I have fired, as loaded by the ammunition factories. This trait can be improved upon by handloading. Therein lies its fascination.

As a defense or hunting load, the factory .44 Special is on a par with the .45 ACP and the .38 Special – both notoriously poor performers. Commercial cartridges in .45 Colt, .44-40, .38-40, and .357 Magnum far outshine the leisurely moving, roundnosed .44, which for generations has maintained its staid, 760 fps pace. But put a bullet of the right configuration over a .44 Special case, crackling with enough of the right, slow burning powder, and its superiority to any of the above-named killers is so apparent as to make comparison a waste of time.

The .357 Magnum, with much justification, has enjoyed a heyday since 1935. Smith & Wesson’s advertising for this revolver used to proclaim, “The S & W ‘.357’ Magnum Has Far Greater Shock Power Than Any .38, .44, or .45 Ever Tested.” With factory loads, this was true. Handloaded, the .44 Special made the .357 – also handloaded to peak performance – eat dust. It was the case of a good big man beating hell out of a good little man.

Basic mathematics made it obvious to experimenters that if the .44 Special were loaded up to its maximum velocity – generally accepted as 1,200 fps at the muzzle with 250-grain bullets – it could skunk the 158-grain .357 slug at 1,500 fps.

Topped with cast bullets in Hollow-point form, both the .357 and .44 Special handloads ran several times higher than their closest competitors on General Julian Hatcher’s scale of relative stopping power. Significantly, the .44 had almost double the stopping effect of the .357 when this scale was applied, in spite of its moving at 300 less velocity.

Homebrewed work loads for my .44 were originally based on the excellent Lyman 429244 cast bullet, in both solid and hollowpoint form. For me, this was a natural choice of bullets after having found the .357 version of the same design – 358156 – to be an extremely accurate one in my guns of that caliber, and to shoot at maximum velocities without leading.

My gorgeous custom Colt ate up many hundreds of heavy loads with this bullet before I realized that the gascheck, so necessary to prevent leading in hot .357 loads, served no good purpose in the .44 Special. Lyman 429421 molds, throwing the well-known Keith Semiwadcutter bullets in both solid and hollowpoint forms, were acquired. The Keith Bullet, cast in a 1 in 15 tin-to-lead mixture, gives minimal leading problems in the .44 Special, and is fully as accurate as the gaschecked 429244 when care is taken in casting.

Some critics of the 429244 say that this gascheck bullet, designed by Ray Thompson, can’t be as accurate as a plain base bullet because the copper cup at its bottom prevents it from slugging out and forming a gas seal in the barrel. This, the detractors claim, allows hot gases to squeeze by the bearing surfaces of the slug, misshaping it and prematurely eroding the bore of the revolver. I have not found this to be so, and heartily recommend the gascheck version to everyone who is willing to go the extra trouble nad expense necessary to produce it. Because of the perfect bullet bases provided by the preshaped gaschecks, the Thompson guarantees accuracy, and I Supect still slugs out to form as good a gas seal as any plain base bullet.

I chose the Keith design because I found it possible, through careful casting, to produce bullets that would perform as well without the necessity of fiddling with the little copper cups.

Solid or hollowpoint, these forty-fours are deadly, and can’t be bettered as manstoppers by any cartridge other than the .44 and .41 magnums, equally properly loaded. My heavy load for police work or big game shooting is an easy one to put together. Size either the Thompson or Keith bullet to .429″ for Smith & Wesson or Ruger guns, .427″ for Colts. Seat this bullet over 17½ grains of Hercules 2400 powder and cap with CCI Magnum primers. If you can shoot a pistol, this load will arm you better than you would be with a 30-30 rifle.

This is a maximum load, and it is unlikely that it will be employed exclusively by men who shoot a great deal. For an intermediate cartridge of around 1,000 fps, 8½ grains of Unique serves well, and outperforms most factory pistol cartridges of any caliber. Charges of 6½ grains of 5066 or 5 grains of Bullseye with either the Lyman 429244 or 429421 bullets will give fine, about-factory-velocity, performance.

For normal to medium-heavy charges, almost any pistol, shotgun, or fast rifle powder may be used for the .44 Special. The Alcan and Red Dot Shotgun powders give singular performance, as well as such slow burners as Du Pont’s IMR4227. A comprehensive list of un-tempermental .44 loads will fill books.

The .44 Special is versatile. Although recommended by some of the more magnum-minded as being a fine deliverer of such small table game as cottontails, squirrels, and grouse, it is a bit severe on these edibles when loaded with full or semiwadcutter bullets, usually leaving a great deal of good meat mangled or bloodshot. Lyman, as well as other mold makers, offers several roundnosed bullet styles and weights that penetrate your entree with no more damage than a .38 Special

If making your own bullets holds no appeal, excellent commercial ones are available. The 240-grain Norma, jacketed in mild steel under a soft nose, serves well as an all-around number, although it doesn’t expand spectacularly at lower velocities. The various swaged bullets, with copper base cups covering their pure lead cores, are very good. Speer Bullets, among many others, merchandise an excellent .44 Semi-wadcutter. And don’t forget the super accurate factory load’s usefulness for small game. The cheapest cases for reloading can be obtained by fireing these loads that shoot so pleasantly.

I’m a little saddened by the fate of the .44 Special sixguns. My first custom Colt cost almost $200 just a few years ago. Acceding the rule of supply and demand, it was worth the price in terms of enjoyment and education. Smith & Wesson finally got some of their 1950 Target Models on dealer’s shelves in 1954.

I bought one of the first, and immediately returned it to the factory to have its 6½” barrel cut to 5″ and a ramp front sight installed. The factory later offered these revolvers with 4″ barrels and ramp sights on special order, and they were a superb law enforcement weapon, selling at a discount to police officers. Hunter who knew handloading grabbed eagerly for these target-quality revolvers and recorded many big-game kills, form deer to Alaskan brown bear.

Scarcely two years of readily available .44 Specials were enjoyed by those who wanted them before the .44 Magnum was foaled in 1956. There can be no argument the the Big One did in all others who vied for top berth in the power department.

Remington’s sensational 240-grain lead bullet at 1500 fps gave even the most power-mad pistolero more than he bargained for. Whimpers were heard from effete shooters who allowed that shooting the .44 Magnum compared to the sensation of burning bamboo splinters being driven into the palm.

While touching off the Magnum is far from being that rough, it is true that few want to shoot a steady diet of full charge loads in it. It results in .44 Magnum shooters loading their big guns down to more palatable levels. A favorite “heavy” cartridge for .44 Magnum devotees is comprised of the Keith or Thompson bullet over 18 grains of Hercules 2400, although the acceptable maximum with these balls is 23 grains. This about duplicates the old, proven .44 Special handloads, and is, in truth, adequate for about any situation a six-shooter man may face.

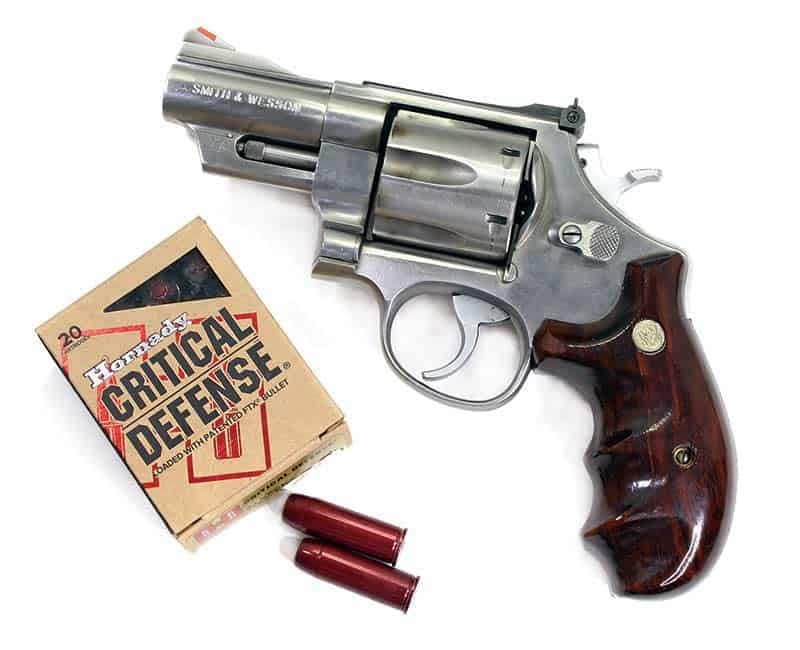

Hearkening to their siren cry I bought every variation of the .44 Magnum that was commercially produced. In the process I rid myself of all my fine, proven .44 Special guns. Sheriff of a Texas County, I felt the need of a powerful holster gun, and dallied with the S & W .44 Magnum in 4″ length.

With factory Magnum or full-powered handloads, its recoil was so pronounced (although not painful) as to make it a poor choice for strings of double action shots in combat situations. Loading it down rendered it no more potent than a .44 Special, and I soon traded it for one. Along with others, I hounded Smith & Wesson for a .41 Magnum, whose two factory loadings would bracket the needs of police officers who did not handload. Since introduction of this revolver in 1964, it has been the best choice for that purpose.

The .44 Magnum is odds-on the selection as a hunting handgun. Because that is what it is, there is small reason to ever load anything but heavy loads for it, and so is my Ruger loaded.

So now the fallen knight, the one-time expensive glamour boy can come out of hiding. Forty-four Specials dirt cheap, with used 1950 Military Smith & Wessons and rebuilt Colt New Service and Single Action Armies going for 50 to 60 bucks. Smith still makes their 1950 Target Models, but rumor has it they may stop. This will leave only the horse-and-buggy Colt single action available in that caliber, if you crave a brand new gun.

Cops need sidearms that will use powerful, store-bought ammunition, and thus should stick with the .357 and .41 Magnums. The everyday man who bolsters a handgun for come-what-may eventualities cannot improve on a .44 Special revolver.

If he owned a higher-priced .44 magnum, he would likely load it down to Special capabilities. With factory ammunition, the Special shoots as accurately as any revolver yet made. Although capable of taking any game that the Magnums can, the old .44 carries half the price of its Magnum “betters.”

A big, holstered sixgun is no longer part of my work, but when I get the chance, I roam in the brush country where a rattler, a whitetail buck, or a javelina might join me at any moment. I have a .44 Magnum, but my .44 Special seems more relaxed – and prettier. Buying a Colt New Frontier Model, with its beautiful blue and old style, mottled, casehardened colors took me back 15 years.

A lot of money is being spent by romantic types who want a big pistol and a little, lever action saddle carbine chambered for the same round. The general approach toward satisfying this craving is to have a Model 92 Winchester .44-40 rebarreled to handle .44 Magnum cartridges. This is expensive and results in a rifle very little more effective than it would have been with hot .44-40 loads. Further, the straight cases of the Magnum rounds often cause exasperating feeding problems in these little actions.

My solution is simpler – change the revolver instead of the rifle. Digging around in my bag of tricks, I fished out an old, but solid, .44-40 cylinder from a forgotten Colt single action. It slipped readily into battery in my sleek New Frontier Model, indexed crisply, and locked up tight. Groups fired with factory .44-40 ammo are adequately tight, opening up another career for my Frontier.

This finely fitted single action suits me well, and is the epitome of the forty-fours I dreamed of for fruitless years. At $150, it seems at first of little overpriced. But then – I once spent more.

Nah as I like wood on my rifles!

YOUR GUN SPEAKS…

WHAT CAN IT TEACH YOU? BY CLAYTON WALKER

Sometimes, it’s the kit, not the gat. Gloves often make

Sometimes, it’s the kit, not the gat. Gloves often make

big guns and very tiny guns more shootable.

I’m going to guess you’ve been in a similar situation to what I’m about to describe. First, you see a new gun — perhaps in our pages here, maybe in a consignment counter of a local shop. You initially tell yourself you don’t need it, but then you crack and find yourself reading reviews and browsing pictures on the internet. Willpower fully sapped, you head to the store and empty your wallet. You give it a good function check, racking slides or cocking hammers, and your head spins with just how cool this thing is going to be once you get to the range.

The days move slowly as you deal with the usual commitments and drudgery. The kids need to get dropped off or picked up from somewhere, projects need to be completed for work, dinner needs to be put on the table, and there’s no end of household chores that need to be put to bed. But at long last, you find yourself the beneficiary of unallocated time. Guns and ammo are collected, the jalopy is gassed up, and you make the trip to the range. Eye and ear protection is donned, your new acquisition is raised to the target, and your index finger begins to take up pressure on the trigger.

One minute later, you’re staring at a mediocre group. Maybe you’ve missed your target entirely. And just like that, it seems you’ve fallen entirely out of love.

On one hand, life is short, and if you sold off every firearm that didn’t bring you constant, unmitigated joy and 100% effortless shooting, I wouldn’t fault you! However, there have been more than a few pieces in my personal collection that I might not have appreciated fully the first time I shot them but have since taught me something and made me a better shooter in general.

In fact, I’d argue more people fall out of love with all of the handguns I’m about to mention than any other — they can make a very poor first impression. However, I’ve since learned to love them, and I’d be a far worse shot if I impulsively kicked a lot of these purchases to the curb.

Range and dry-fire practice with a magnum handgun can

Range and dry-fire practice with a magnum handgun can

really target recoil tolerance and anticipation!

The Magnum

Most men feel like they can drive fast, cook, make love and shoot magnum handguns without ever feeling like they need to put in the work to actually become proficient. Lots of people saw Dirty Harry back in the day and pined for what was then “the most powerful handgun on earth.” After about a few cylinders of big bore, full-power .44 Magnum out of S&W’s Model 29, no shortage of owners turned 180 degrees and marched that sixgun right back to the gun store — along with a half-full box of ammo.

I’m of the distinct opinion that shooting the magnum handgun requires more than just holding it in the general direction of one’s target, pulling the trigger and hanging along for the ride. I think you also need to hit what you aim at. Unfortunately, recoil has long been a detriment to realizing good accuracy, and our reptile brains are hard-wired through millions of years of evolution to freak out (if only a little bit) when we hear a gigantic boom.

Often, the fight-or-flight reflex that accompanies the first round of magnum handgunning produces an adrenaline dump that makes fine motor manipulations more challenging. Slow, careful trigger presses often turn into exaggerated mashes, particularly among novice and intermediate handgun shooters.

However, the magnum handgun is undoubtedly “expert mode” when it comes to teaching careful and deliberate trigger manipulations and learning to fight one’s way back through stress and adrenaline is immensely valuable. I’ve found the real-deal magnum handgun to be excellent when it comes to magnifying any bad habits one has in terms of recoil anticipation and providing an immediate opportunity to correct them.

Additionally, after one gets some trigger time on a .44 Magnum (or bigger!), it’s funny how the recoil of just about any other self-defense cartridge ceases to be a big deal. Once you know how a gun can bite, twist, or buck under heavy recoil, you become that much more appreciative of anything that makes a well-mannered pop and settles back down in the hand.

SIG’s P229 and Wilson Combat/Beretta’s 92G offer great

SIG’s P229 and Wilson Combat/Beretta’s 92G offer great

advantages to those who learn the DA trigger.

A small “TDA” design, the Beretta 84 requires dedication and patience to fully harness what it has to offer.

A small “TDA” design, the Beretta 84 requires dedication and patience to fully harness what it has to offer.

Another great take on the “Traditional”

Another great take on the “Traditional”

Double-Action auto: CZ’s SP-01.

The “Traditional” DA

About 10 years ago, a lot of the common dogma on the internet seemed to favor striker-fired autos. There was a distinctively sour note when it came to those asking about the viability of the Beretta 92, S&W “Third Gen” autos, or even H&K’s USP series. “It doesn’t make sense to try to master two trigger pulls,” opined the self-appointed experts. “Just pick a platform where you only have to get good with one.”

A few people I knew competing in IDPA bought into that methodology fully — even problematically. If they did have to compete with a DA/SA auto, they saw the first shot almost as a throw-away. “Might as well just mash the trigger and get that first round over with,” said one shooter. It was a perspective that could, in some cases, work out okay in matches with lots of close targets, though I hope we all recognize how this could create a liability if one adopted the same philosophy with a CCW piece. As I heard it first from Clint Smith, “Every bullet has a lawyer behind it.”

In reality, it might surprise a few people to hear I’ve had fun mastering two separate trigger pulls. In most cases, the DA pulls of most autos are heavier in comparison to revolver triggers, a platform I was once far more familiar with. I couldn’t really “stage” a DA auto trigger. Instead, I had to learn better techniques to get the trigger moving and continue through the motion fluidly until the shot finally broke. Even a mediocre DA auto trigger often behaves fairly predictably: Don’t start and stop. Make a commitment to the pull and execute consistent, increasing pressure until the resistance seems to drop off the proverbial table.

Surprise, surprise: I now often shoot DA/SA autos better in the DA mode simply because of that surprise break. I also very much like the peace of mind that comes with employing these guns for CCW or home defense with the chamber loaded and the hammer down, ensuring that the first round can only be fired with care and deliberation. My DA familiarity has also made me a much better revolver shooter, to boot!

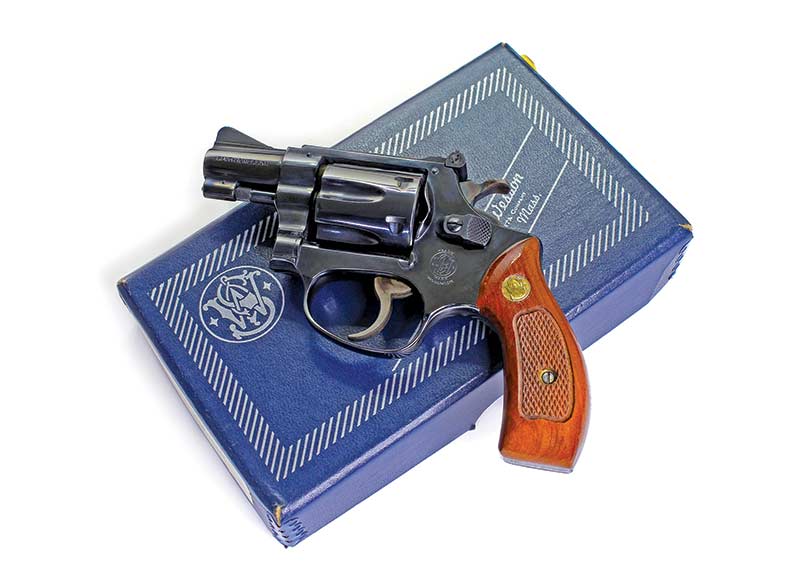

Double-challenging: S&W’s Model 34 is small and has

Double-challenging: S&W’s Model 34 is small and has

a stiff DA pull. Hits are earned!

The Mouse Gun

Perhaps no handguns produce more of a palpable difference between expectation and reality than itty-bitty guns. They look cute and unassuming — something, maybe, your wife, daughter, or grandma could handle and instantly start shooting like Annie Oakley, right? At the very least, shouldn’t a big, strapping man be able to wrangle something so Lilliputian with total ease?

The fantasy typically dies after a few presses of the trigger. Often, the mouse gun’s drawback is similar to that of the magnum handgun: They’re typically not easy to shoot due to aggressive, snappy recoil. Sure, the guns are small, but they’re often chambered for defense-capable rounds like .380 ACP and .38 Special. Some can be downright painful under recoil.

However, even if they’re comfortable to shoot, design constraints present their own challenges. They’re hard to grip, making them susceptible to point-of-aim variations due to grip inconsistency. They don’t have a lot of mass, so it’s easier to push the muzzle to and fro in the event of a mash. A majority of designs depend on tiny, hellaciously stiff springs to power slides, hammers and other working parts — as a result, their triggers tend to suck.

Getting good at shooting a mouse gun means adapting to a platform that is flat-out working against you. It requires more on all fronts: more attention to the light on both sides of the front post in the rear notch. More consciousness of pulling the trigger straight back, even through greater resistance. More mindfulness of how the dominant hand interfaces with the tiny grips and if one’s “natural” point of aim is actually pointing the firearm where you want it to.

But work through those idiosyncrasies and I guarantee you’ll feel like you’ll have well and truly earned your hits. The mouse gun accepts absolutely nothing less than excellence, and as a result, it can be a superb coach for a shooter who wants to push their abilities and get to know how solid (or shaky) their fundamentals truly are. “Not good enough,” the mouse gun often says. “Run it again.”

Small but well-made firearms like the GLOCK 42 and Beretta 70 nearly always outshoot their owners.

Small but well-made firearms like the GLOCK 42 and Beretta 70 nearly always outshoot their owners.

Tiny sights and a short sight radius complicate

Tiny sights and a short sight radius complicate

(but don’t obviate) good hits!

Hard Fun?

I have many handguns in my collection that feel like an extension of my arm that seem to put bullets exactly where I want them. Many guns didn’t require any kind of warm-up, break-in period, getting to know their quirks, or whatever else: I just aimed them at the target, and they seemed to do my bidding! At the end of the day, I have to admit I like hitting more than missing.

However, there’s been a good 30% of my collection that I’ve had to come around on. Most fit one of the above three categories. Over a decades-long, getting-to-know-you period, they’ve shown me that as far as handgun accuracy goes, and in the overwhelming majority of contexts, “It’s the Indian, not the arrow.” I’m a better shot for not having ditched some guns that stymied me as a younger shooter, and today, I appreciate the extra level of challenge in having to work a little harder for a clean hit.

Again, some guns won’t meet you where you are. But before you angrily sell a seemingly non-compliant heater for less than you paid, ask yourself whether it can be a tool to get your skill set to where you want it to go. Its foibles might turn out to be features, after all.

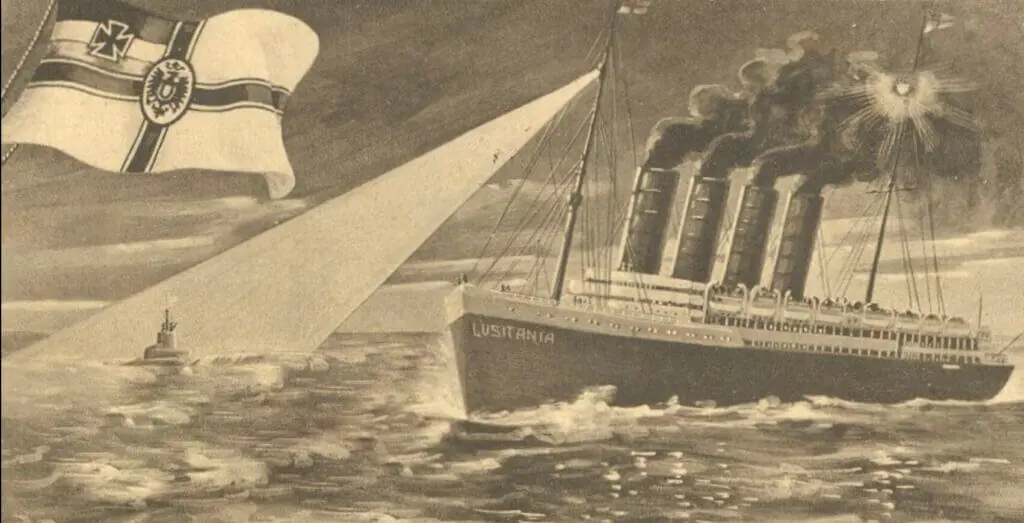

We drape our wars in a thin layer of respectability, but we are still just bloodthirsty animals at heart.

We drape our wars in a thin layer of respectability, but we are still just bloodthirsty animals at heart.Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

War is the most uncivilized of human pursuits. If you think about it, it is mind-boggling we’re still doing it. One nation-state gets cross with another, and the next thing you know we are slaughtering each other’s young folks wholesale. It seems there’s not such a grand gulf between us and the beasts of the fields after all.

Table of contents

We couch the practice underneath a veneer of respectability. Our finest strategists earn advanced degrees in the prosecution of modern war, and our military-industrial complex drives technical innovation on an unrivaled scale. And yet at its heart, the true mission of the military is to simply rip the very life out of other human beings who would, in general, really sooner not be there.

Martial Philosophy

If I’m coming across as a pacifist, I’m not. The world is a dangerous place, and our adversaries are frankly insane. Whether it is ISIS, Hamas, Boko Haram, al Qaeda, or the Russians you happen to see over your rifle sights, you’d best be metaphorically ready to pull that trigger. Rest assured were the roles reversed those guys would not be particularly morally encumbered.

It is, however, essentially impossible to excise emotion from that equation. No matter how civilized we claim to be, the very act of war is an innately barbaric unrestrained thing. It is for this reason I am philosophically opposed to embedded reporters in war zones.

War is ugly, horrifying, and bad. Our young studs have enough on their minds without having to fret about their actions being broadcast into living rooms across America. If it is important enough to go to war I think we should just get out of the way and let our warriors take care of business. Turns out I’m not the first guy to feel that way.

Setting the Stage For Baralong

World War 1 was a transformational event in human history. This vast conflict was the planet’s rude introduction to combat on a truly industrial scale. The learning curve was steep.

Previously it was a fairly straightforward thing to fractionate war into combatants and everyone else. On 21 July 1861, droves of civilians showed up with food to spectate during the First Battle of Bull Run. They arrived expecting a gay holiday, initially referring to the ominously pending event as the “Picnic Battle.”

The end result was more than 4,000 killed and wounded and an irretrievable loss of innocence for all involved. Come World War 1, all pretense of civility was gone. Technology had rendered chivalry and restraint obsolete.

The U-boat Scourge

In no place was this lamentable reality more starkly manifest than in the burgeoning art of submarine warfare. The concept of the combat submarine was brand spanking new, and the Kaiser’s Navy led the technological charge. Now a warship could approach a target submerged and strike from a position of stealthy advantage.

It also became increasingly difficult to differentiate between men of war and transport ships fat with civilians. Sometimes those transport vessels had their staterooms packed with civilians and their holds full of war materiel. The end result was the perfect recipe for tragedy.

That tragedy struck in May of 1915 with the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by U-20, a German U-boat. The Lusitania was a passenger liner on its 202d transit across the Atlantic carrying some 1,962 passengers and crew. U-20 centerpunched the fast liner with a single torpedo just beneath the wheelhouse.

The massive ship sank eighteen minutes later, carrying 1,199 souls to the bottom with her. That number included a great many British women and children as well as 123 Americans. Once word of this attack made the rounds, the sailors of the Royal Navy were disinclined to show much mercy to German U-boat men.

The Rules Change

This bloodlust was fairly institutionalized. In the aftermath of the Lusitania sinking, two officers of the Admiralty’s Secret Service branch approached Lieutenant Commander Godfrey Herbert, skipper of the British Q-ship HMS Baralong, saying, “This Lusitania business is shocking. Unofficially, we are telling you…take no prisoners from U-boats.” Herbert took his new directive quite literally.

At this point in the war, the Q-ship was England’s best weapon against U-boat attacks. These heavily armed merchant vessels masqueraded as helpless transports to lure U-boats in close before exposing hidden guns and sending many a submarine to the bottom. Torpedo technology was still in its infancy, so much of a U-boat’s firepower came from its deck guns. U-boats would often approach a target ship via stealth and then surface to prosecute the attack. Q-boats were designed to feed that right back to the Kaiserliche Marine.

Personalities In the Baralong Incident

LCDR Herbert was not your typical Royal Navy ship’s Captain. He purportedly encouraged his men to terrorize the countryside in drunken binges while on shore leave.

In one sordid incident in Dartmouth, several of his sailors destroyed a local pub and were arrested. Herbert paid their bail personally and then returned to sea as soon as everyone was accounted for. He also inexplicably insisted on his crew calling him “Captain William McBride” to his face.

In August of 1915, a German U-boat sank the liner SS Arabic while within 20 miles of the Baralong’s patrol area. The Baralong made haste to the site but failed to recover any survivors. This left Herbert’s crew in a proper state. Meanwhile, about seventy miles away, the German U-boat U-27 had intercepted the British steamer Nicosian.

Battle is Joined

The skipper of U-27, Kapitanleutnant Bernd Wegener, led a six-man boarding party to search the Nicosian. They discovered war materiel and 250 American mules making the transit over to assist with the war effort. As a result, Wegener ordered the crew off the Nicosian and prepared to sink her with his deck guns.

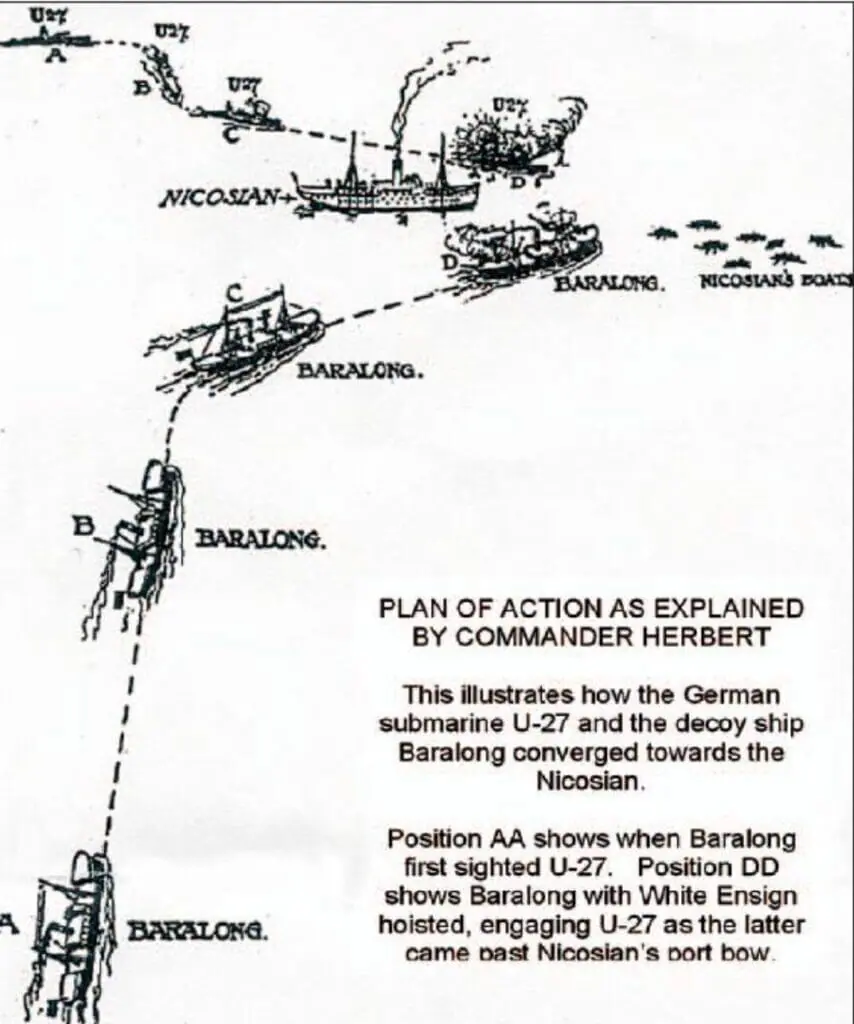

HMS Baralong arrived at the site of this little nautical dustup intentionally flying an American flag. Under the false guise of neutrality, the Baralong maneuvered within 600 yards of the U-boat, claiming their mission was to rescue survivors. U-27 held fire and assumed a course parallel to the stricken Nicosian.

Meanwhile, the Baralong adopted an identical course on the opposite side of the doomed British ship. Once the Nicosian effectively masked the Baralong, Herbert exposed his guns and prepared for surface action. As soon as she cleared the Nicosian, the Baralong opened up with everything she had.

Raw Firepower Trumps Absolutely Everything

Baralong was equipped with three big 12-pounder guns. These quick-firing 76mm cannon could fire a blistering 15 rounds per minute. Their withering fusillade overwhelmed the wallowing U-boat in short order.

Once the engagement was decided, Herbert called for a cease-fire. However, his crew ignored the order, incensed as they were over the recent loss of civilian life to the cowardly U-boats. The Baralong got off 34 rounds for the U-boat’s one. Now thoroughly ventilated, U-27 rolled over and began to sink.

Up until this point, things were sort-of unfolding according to accepted convention, the confusion over the spurious American ensign notwithstanding. However, the Nicosian crew was goading the British sailors from their lifeboats, shouting, “If any of those bastard Huns come up, lads, hit ’em with an oar!”

A Dark Turn

Twelve German sailors escaped the stricken U-boat before it slipped under. These were the deck gun crews and those men on duty in the conning tower. They dove into the water and swam for the Nicosian, now occupied solely by the German boarding party.

Herbert later claimed at an inquiry that he feared the Germans would scuttle the defenseless civilian vessel. As a result, he ordered his men to gun down the U-boat survivors with small arms. They did so willingly, killing every last one of them as they floundered in the sea.

Herbert then dispatched his 12-man contingent of Royal Marines in a small boat under a Corporal Collins to the Nicosian to root out the surviving Germans. As they departed the Baralong, Herbert publicly ordered them to, “Take no prisoners.”

It Gets Worse For The Germans

The Germans had taken refuge in the freighter’s engine room. Collins and his Marines cut them down to a man. Some reports had Kapitan Wegener having hidden in a bathroom. The Royal Marines supposedly broke down the door with their rifle butts, and the German officer dove into the water. Collins then purportedly took careful aim with his revolver and shot the German U-boat skipper through the head.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the British Admiralty ordered the report suppressed. However, there had been Americans among the Nicosian’s survivors in the lifeboats, and they spoke with newspaper reporters upon their return home. The sordid details of the exchange soon circled the globe.

Not unexpectedly, the Germans had a veritable conniption, threatening a variety of unspecified reprisals. However, the two nations were already at war. This seminal event did, however, drive the German Navy to abandon the accepted Prize Rules wherein some modicum of restraint was shown toward target crews and embrace unrestricted submarine warfare. Countless more subsequently perished as a result.

Damage Control On the Baralong

To help protect the Baralong and her crew from the Germans should she ever be captured, the ship was renamed HMS Wyandra. The name Baralong was deleted from the Lloyd’s Register, and the vessel was assigned new duties in the Mediterranean. Regardless of their having committed unfettered murder, the crew of the Baralong along with her Captain were awarded a 185-pound bounty for having sunk the German U-Boat U-27.

It has been said that, in war, the victors write the history. This is undoubtedly true. LCDR Herbert and his crew certainly committed a war crime in machinegunning the helpless survivors of U-27 after crippling their vessel. However, the Germans were sinking ocean liners filled with civilians at the time. As a result, nobody really much cared.

LCDR Herbert was an unscrupulous brigand who managed his warship beautifully. He approached the scene of the battle under a flag of truce.

LCDR Herbert was an unscrupulous brigand who managed his warship beautifully. He approached the scene of the battle under a flag of truce.