I found these on Pinterest. So I thought would share the results of some one’s great skill and talent to make these great looking rifles .

Here is their email address

CUSTOM RIFLES GALLERY

I found these on Pinterest. So I thought would share the results of some one’s great skill and talent to make these great looking rifles .

Here is their email address

A Fantastic Tribute to the Art of High End Gunsmithing!

Just look at the engraving alone! They look like to me to be “Yellowboy” Winchester Model 1866 on the right.

I do not know what the one on the left is. Maybe a Winchester 1873? Or it may be a Reproduction? I also wonder what calibers they are in?

All I know is that you will not see their like for sale at Walmart!

Here is also a pretty good picture. Of the inside guts of what these guns look like. The simplicity of it is just stunning!

Can you imagine what the recoil must be like? That & where do you hold on to it? Supposedly it is in 12 gauge.

As I was zooming thru the Net. I spied upon this little nugget of information. So being the Shameless thief that I am. I thought that there might be an interest about this subject. I hope that you wonderful folks out there will like it.

Grumpy

“Phil, we’re going to pass on him; he’s just a bit too short for what we’re looking for.”

The author with the Heym 89B in .470 Nitro Express, and a huge bodied Australian water buffalo. Photo Courtesy: Stealth Films/Steve Couper

Really? The bull was as dead as yesterday, comfortably wading in the billabong, completely oblivious to the hunters standing 40 paces away behind the shade tree on the bank. But, professional hunter Graham Williams was very serious, and all I could do was draw the rifle down on the buffalo and count coup. Something in my body language must have expressed frustration, and the ever-cool Willams uttered what I would soon learn was his catch-phrase: “Please be patient, there are many bulls to be looked over.” I shouldered the big German double, and continued on the buffalo trail beside the series of waterholes that dotted the small valley.

It had been a journey of epic proportions; the East Coast weather in the U.S. caused me to miss my connecting flight, and therefore the flight to Sydney. That wrinkle, coupled with the rigidity of the Australian firearms policies and a lost rifle and baggage made for a stressful couple of days. In camp already, my partners and cameraman were on the hunt, and I was sitting in Darwin waiting for gear. No worries, I was just 36 hours late, but I had arrived. The charter flight was smooth and we saw some good water buffalo bulls and a trio of wallabies on the drive into Graham Williams’ remote camp in Arnhemland, in the Northern Territory of Australia.

The hunt was a combination of work and play; we were filming an episode of Trijicon’s World of Sports Afield, but it was with a group of friends that enjoyed hunting together. Chris Sells, head honcho at Heym USA, had put the hunt together, and his buddies John Lott and John Saltys were along as well. Chris and I had a purpose: to put the Heym Model 89B double rifle — chambered in .470 Nitro Express — through its paces. It wasn’t my first jaunt with the 89B – I had the privilege of taking the first animal, a Cape buffalo bull, with the 89B in .450/400 at the end of 2016 — but it would be a great opportunity to play with the rifle chambered in .470 Nitro Express. Arnhemland is comprised of mostly Aboriginal land, and the hunting operations provide a source of income for the indigenous peoples, in addition to keeping the water buffalo population in check. You see, the Asiatic water buffalo – Bubalus bubalis – was introduced to the Northern Territory in the 1830s, and have since gone feral. Australia classifies them as an invasive species, and they are readily hunted for sport and for meat. Easily weighing over a ton – bigger than any Cape buffalo in Africa – the bulls take a pounding and can soak up a lot of lead. Using a double rifle makes a lot of sense, as the Arnhemland terrain provides enough cover to allow for a good stalk, and the shooting tends to be at close range.

For the big game hunter who’s looking for the best value in a double rifle, the Heym 89B is undoubtedly at the top of the heap.

With a rounded boxlock action, squared at the rear, the Heym 89B offers classic British styling mated with German engineering; truly a sound marriage.

The Heym Model 89B is a perfect choice for this style of hunting, and the .470 Nitro Express is a classic, rimmed, double-rifle cartridge that has proven itself on any and all dangerous game animals, including the African elephant. Ah, the 89B! If you’re a student of dangerous game rifles, I’m certain you’ve heard the Heym name before, and I’m equally sure you are familiar with their Model 88B double rifle. Well, the 89B is the heir to the empire, the successor to the throne. It maintains the same inner workings of the 88B – a highly dependable boxlock – and pays homage to the classic Anson & Deeley design, including the Greener crossbolt and disc-set strikers. That is where the similarities end.

Ammunition for the water buffalo hunt was built with 500-grain North Fork cup solids over Alliant Reloder 15, in Hornady cases. Velocities were at the standard 2,150 fps mark.

When I first held the Model 89B, I immediately noticed the difference in the stock design. German-born gunmaker Ralf Martini was brought in again – he had an integral part in designing the Heym Express by Martini bolt-action rifle I love so much – and formulated a stock design that emulates the classic pre-war British doubles. A sweet, sloping pistol grip – with an angle more relaxed than that of the Model 88B – is designed with a smaller circumference fits perfectly in the hand. In addition, the smaller, sloping forend – in the classic splinter design – gives a firm grip yet none of the bulk or weight of the huge beaver-tail forend designs. The nose of the comb has been moved rearward, and the overall stock design is fundamental to keeping the balance point and weight of the rifle between the hands, to ensure a sweet-handling rifle that is characteristic of the classic double rifles of a century ago. And sweet it is! If you’ve ever handled those classic designs – the Webley & Scott, the Westley Richards – you’ll find the Heym Model 89B to be an immediate friend; it’ll feel like you’ve known each other for years.

Famed stockmaker Ralf Martini was brought in to design the Heym 89B stock, and did a fantastic job creating stylish and ergonomic furniture.

But the stock is only the beginning. During the design process, which took up the better part of a decade, the action and barrels also received an overhaul. Where the 88B has a signature look at the back of the action, with the wood jutting into the rear metal of the action, the 89B has a square action at the rear, in the classic fashion of the Webley P.R.V. 1 action. In comparison to the 88B action, many of those square edges have been rounded – especially on the top and bottom of the action – and some well-placed stippling adds a bit of flair to the action’s top. Heym saw fit to produce another frame size: a larger frame for the .470 Nitro Express and its big brother the .500 Nitro Express.

The splinter forend gave a positive grip, with none of the bulk of the larger beavertail forend designs.

The barrel contour was also made slimmer, once again to put the balance of the rifle between the shooters hands. While this may not seem like such an important feature, trust me when I tell you that the handling of a gun designed specifically to serve on a dangerous game hunt is paramount. The barrel is topped off with a rear sight bedecked with a gold vertical line and some anti-glare stippling on the primary sight, with flip up leaves for further yardages. The bold front bead is filed flat, one of the little things that Heym does to enhance performance. The rib is machined to accept either the Trijicon RMR red-dot or the Docter sight; this is one feature we took full advantage of in Australia. While I used the traditional iron sights in Mozambique for my Cape buffalo, Australia does have some terrain where the shots are in open country, and the Trijicon RMR RM09 – with the oneMOA dot – makes life easier when distances approach 100 yards. As you’ll see shortly, that Trijicon was put to the test and came out shining. The rifle was certainly accurate enough, putting a right and a left within an inch of each other at 50 yards. The Heym rifles are regulated with Hornady ammunition, but for our hunt, we developed a load around the 500-grain North Fork Cup Solid, a bullet designed for all sorts of penetration, with a small cup at the nose for just the slightest hint of expansion. Fueled by Alliant Reloder 15 and clocking in at 2,147 feet per second (fps), this load regulated perfectly, and I was eager to see the performance on those huge Australian bovines.

The twin triggers of the 89B broke cleanly and crisply, offering two quick shots for a perfect dangerous game setup. Photo Courtesy: Stealth Films/Steve Couper

So, with this new frame size, in a rifle with undeniably classic lines, chambered in a time-proven caliber, Graham Williams, Chris Sells and I headed into the Australian bush to stalk some bulls. I was up first, and once I had that encounter with the bull in the billabong, I began to see why Mr. Williams insisted on my patience. Apparently, that bull was positioned at what we dubbed The Valley of the Bulls, as we immediately bumped into several bigger specimens, with Graham pausing an extra bit to glass a distant bull, quietly feeding in the tall grass on a slight hillside. “Do you see that bull Phil? The big one feeding up there?”

A good, bold front sight is easily picked up by the shooter’s eye. HeymUSA has the bead filed flat to reduce glare and allow for more precise shot placement.

“The one with the pink horns? Does he seriously have pink horns?” I asked.

“It’s the color of the soil; it has many different shades and changes quickly in this area. That’s a damned good bull, and we need to take him, but the wind is going to be tricky. Follow me, stay low, and if we bump another bull, stand still and let it pass.”

Aye, aye, Cap’n – right behind you. We had spotted the bull from 350 yards or so, and while he was in an open area dotted with trees, the trees got a bit thicker off to his right, and we used those trees for cover to make an approach. Along the way, two younger bulls had caught our movement, but luckily enough bounded off without too much noise; we felt good that things weren’t disturbed too badly.

Graham and I stopped long enough to have a discussion, or perhaps a debate, about where the bull last was in comparison to where we were heading. During the talk, we simultaneously spotted those pink horns again, this time we watched him lay down about 100 yards off. Slowly, furtively, quietly we snuck from tree to tree, hoping to get good and close to the bull. There was no doubt that he was the bull we wanted to take; he had great mass and was immense in the body. The distance shortened from 50 yards to 30 yards, as Graham and I tiptoed from paperbark tree to paperbark tree, then shortened to 25 yards as I began to question exactly how close he wanted to get. Thumb firmly planted on the 89B’s safety, we ran out of trees at 17 yards, and the bull knew something was up. He got up quickly, but not quickly enough and the 89B floated to my shoulder. The shot presentation wasn’t stellar, but I had enough of an angle to see some ribs and just a hint of the shoulder from the bull’s right side; that’s fine, I didn’t have to penetrate that grass-packed paunch on the left side. The Trijicon dot settled just behind the shoulder and I broke the right trigger, immediately followed by the left. The bull stumbled to his front knees, moving straight away from me now, and another North Fork placed exactly at the root of his tail put him down for good. Still, I gave him another between the shoulder blades as he lay twitching on the ground, and only then did I get the exact scale of a mature Asiatic water buffalo: he went well over a ton, probably closer to 2,200 pounds. Huge, worn horns, caked in reddish-pink mud and broomed off at the tips, swept back beautifully, measuring well over 40 inches between the tips. I stood in awe of this magnificent animal, and as the adrenaline subsided, I reflected back on exactly how wonderful the rifle I carried was. That Trijicon RMR was so good I didn’t even notice it, the dot floated onto the target and the bullet went where the dot was. Watching the footage on film, it looked as though I was shooting a lesser caliber than the big .470; such is the case when a rifle fits you properly.

Graham Williams’ camps offered rustic, yet comfortable, accommodations, in a truly vast and wild area of Australia.

Chris Sells had the opposite end of the distance spectrum a couple days later, when a wise, old bull that we had bumped three times stopped at 120 yards to look back, and Sells and the Heym/RMR combo settled the score for good. “Phil, I wouldn’t have tried that shot with iron sights, but that RMR changes the game” Sells confided. The two of us had carried that gun – trading off for my faithful Heym .404 Jeffery for backup – and both enjoyed the weight and balance. Even with 26-inch barrels, the Heym 89B was never cumbersome, in spite of tipping the scales at an even 11 pounds.

The North Fork Cup Solids worked just fine, giving all sorts of penetration, regardless of shot angle, and among three bulls and numerous shots, we only recovered one bullet. Just a hint of expansion and 100-percent weight retention are common features of the Cup Solid, and that’s exactly what we found.

Now if you don’t feel the need to own a good double rifle, I sort of understand, but if you end up in pursuit of dangerous game – and Graham Williams will attest to the fact that water buffalo can and will charge – a double is an excellent tool for close-quarters work. I feel confident, having handled and shot a fair number of double rifles, that the Heym 89B represents the best value on the double rifle market today. They are made to fit the client in both barrel length and length of pull, and in a market where prices can easily get into six figures, the 89B is a means of attaining a dependable and reliable, yet attractive rifle. There are numerous levels of fine wood and engraving patterns to choose from, as well as a caliber for every shooter’s comfort level. How much did I enjoy my couple of hunts with the 89B? I ordered a .470 NE, stocked to my dimensions, and I cannot wait to take delivery.

SPECIFICATIONS

Weight: 11 lbs.

Caliber: .470 Nitro Express (tested)

Action: Break action, boxlock

Barrel: 26 in. steel barrels

Magazine: N/A

Sights: Iron sights furnished, able to accept red dot sights, scope mounts available by special order

Overall Length: 43 in.

MSRP: Starting at ~$21,000US (call for pricing)

For more information about Heym rifles, click here.

For more information about Trijicon Red Dot sights, click here.

For more information about hunting Austrailia, click here.

For more information about North Fork Bullets, click here.

To purchase a dangerous game rifle on GunsAmerica, click here.

![Location of Finland (dark green)– in Europe (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/EU-Finland.svg/250px-EU-Finland.svg.png)

Location of Finland (Dark Green)

The Sniper Version

Poor Finland! Sadly it holds the Record of being the only Democracy that fought with Hitler. Not that they wanted to, I am willing to bet. But when you have Stalin as your neighbor. One really does not have much of a choice. Since it is the Devil or the Deep Blue Sea time.

Now the Finns are a hostage of geography. What with being stuck between the two major powers of Europe. (Germany & Russia)

You also have to remember that the First campaign of conquest in WWII in Europe. Was by Hitler’s then Ally -Stalin. A true Monster of a Man.

https://youtu.be/4Fo7PZzrBVU

So The Finns really did not have a choice on the matter. I mean look at who do you want to have pissed off at you? Pretty tough choice huh?

So the Finns just hunkered down. And then started throwing punches & somehow survived. Due to some great Leadership under this stud of a man.

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Now about the Guns

I have owned a couple of the Mosin–Nagant rifles over the years. During which I have found the Finnish models to be the best of the lot.

That & while they are heavy and bulky. They do shoot pretty well with the Russian 7.62x54r round. Which is a serious man stopper round.

As this guy would heartily agree with down below.

| Simo Häyhä | |

|---|---|

Häyhä after being awarded the honorary rifle model 28.

|

|

| Nickname(s) | White Death |

| Born | 17 December 1905 Rautjärvi, Viipuri Province, Finland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 1 April 2002 (aged 96) Hamina, Finland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | Finnish Army |

| Years of service | 1925–1940 (2) |

| Rank | Alikersantti (Corporal) during the Winter War, promoted to Vänrikki (Second Lieutenant) shortly afterward[1] |

| Battles/wars | Winter War |

| Awards | Cross of Liberty, 3rd class and 4th class Medal of Liberty, 1st class and 2nd class Cross of Kollaa Battle[1] |

Simo “Simuna” Häyhä (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈsimo̞ ˈhæy̯ɦæ]; 17 December 1905 – 1 April 2002), nicknamed “White Death” (Russian: Белая смерть, Belaya Smert; Finnish: valkoinen kuolema; Swedish: den vita döden) by the Red Army[citation needed], was a Finnish sniper. According to western sources, using a Finnish-produced M/28-30 rifle (a variant of the Mosin–Nagant rifle) and the Suomi KP/-31 submachine gun, he is reported as having killed 505 men during the 1939–40 Winter War, the highest recorded number of confirmed sniper kills in any major war.[2][3] However, Antti Rantama (Häyhä’s unit military chaplain), credited 259 confirmed sniper kills were made by Simo Häyhä during the Winter War.[4] Häyhä wrote in his diary, found in 2017, that he killed over 500 Soviet soldiers (by both sniper rifle and machine/submachine gun).[5]

[hide]

Häyhä was born in the municipality of Rautjärvi in the Grand Duchy of Finland, in present-day southern Finland near the border with Russia, and started his military service in 1925. He was the second youngest of a Lutheran heritage family of farmers of eight children.[6] Before entering combat, Häyhä was a farmer and hunter. At the age of 20, he joined the Finnish voluntary militia White Guard (Suojeluskunta) and was also successful in shooting sports in competitions in the Viipuri Province. His home was reportedly full of trophies for marksmanship.[7]

During the 1939–40 Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union, Häyhä served as a sniper for the Finnish Army against the Red Army in the 6th Company of JR 34 during the Battle of Kollaa in temperatures between −40 °C (−40 °F) and −20 °C (−4 °F), dressed completely in white camouflage. Because of Joseph Stalin’s purges of military experts in the late 1930s, the Red Army was highly disorganised and Soviet troops were not issued with white camouflage suits for most of the war, making them easily visible to snipers in winter conditions.[8]

According to Western sources, Simo Häyhä has been credited with 505 confirmed sniper kills.[2] A daily account of the kills at Kollaa was made for the Finnish snipers. All of Häyhä’s kills were accomplished in fewer than 100 days – an average of just over five per day – at a time of year with very few daylight hours.[9][10][11]

However, Simo Hayha’s result is impossible to check, because his targets were always on the Russian side.[12] During the war, the “White death” is one of the leading themes of Finnish propaganda.[13] The Finnish newspapers frequently featured the invisible Finnish soldier, thus creating a heroic myth.[14][15] Depending on the statistics, Häyhä is believed to have killed between 200 to 500 enemies by sniper rifle.[15]

A. Svensson, Häyhä’s division commander, credited Häyhä with 219 confirmed sniper kills, and an equal number of kills by submachine gun, when he awarded Häyhä an honorary rifle on 17 February 1940. In his diary, military chaplain Antti Rantamaa reported 259 confirmed sniper kills and an equal number of kills by machine/submachine gun from the beginning of the war until 7 March 1940, one day after Simo Hayha was seriously wounded.[16]

Some of Simo Häyhä’s figures are from a Finnish Army document (counted from beginning of the war, 30/11/1939):

Häyhä used his issued Civil Guard rifle, an early series SAKO M/28-30 (Civil Guard district number S60974). The rifle was a Finnish White Guard militia variant of the Mosin–Nagant rifle, known as “Pystykorva” (literally “The Spitz”, due to the front sight’s resemblance to the head of a spitz-type dog) chambered in the Finnish Mosin–Nagant cartridge 7.62×53R. He preferred iron sights over telescopic sights as to present a smaller target for the enemy (a sniper must raise his head a few centimeters higher when using a telescopic sight), to increase accuracy (a telescopic sight’s glass can fog up easily in cold weather), and to aid in concealment (sunlight glare in telescopic sight lenses can reveal a sniper’s position). Häyhä also did not have prior training with scoped rifles thus using captured Soviet scoped rifle (m/91-30 PE or PEM) in combat without proper training was not what he preferred to do. As well as these tactics, he frequently packed dense mounds of snow in front of his position to conceal himself, provide padding for his rifle and reduce the characteristic puff of snow stirred up by the muzzle blast. He was also known to keep snow in his mouth whilst sniping, to prevent steamy breaths giving away his position in the cold air.[19]

In their efforts to kill Häyhä, the Soviets used counter-snipers and artillery strikes,[citation needed] and on 6 March 1940, Häyhä was hit in his lower left jaw by an explosive bullet fired by a Red Army soldier.[20] He was picked up by fellow soldiers who said “half his face was missing”, but he did not die, regaining consciousness on 13 March, the day peace was declared. Shortly after the war, Häyhä was promoted from alikersantti (Corporal) to vänrikki (Second lieutenant) by Finnish Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim.[21]

It took several years for Häyhä to recuperate from his wound. The bullet had crushed his jaw and blown off his left cheek. Nonetheless, he made a full recovery and became a successful moose hunter and dog breeder after World War II, and even hunted with the Finnish President Urho Kekkonen.[19]

When asked in 1998 how he had become such a good shot, Häyhä answered, “Practice.” When asked if he regretted killing so many people, he said, “I only did my duty, and what I was told to do, as well as I could.” Simo Häyhä spent his last years in Ruokolahti, a small municipality located in southeastern Finland, near the Russian border. Simo Häyhä died in a war veterans’ nursing home in Hamina in 2002 at the age of 96,[21][22] and was buried in Ruokolahti.[23]

All that I know for a Red Hot Gospel Truth. Is that I would not want him pissed off at me in my Area of Operations!

for your time spent here!

Grumpy

What is there to say about “Old Blood & Guts* “, General George Patton USA? Actually a lot. I am also willing to bet that Folks a couple of Hundred years from now. Will be talking about him and his Career.

To begin with. I extremely doubt that a Character like Patton could survive politically in Today’s Army. (I have heard that he does though have some distant relatives still serving in the Green Machine)

General Patton IV – He was the last direct relative to serve in the Army.

Want to hear him? The man had a very strange voice by the way.

But let us get to part of his gun collection. This what I have been able to find so far. Now I am willing to bet on a couple of issues. So here goes the old fool!

Patton came from Money. He was at the time probably the Richest Officer in the Army.

(There are still a lot of folks in the military. Who do not depend on their paycheck. But you would never know it from looking at them.)

The class of folks that he came from. Are real big on the sport of shooting, riding & fishing.

I am also been told by folks that I believe. That if you were in Europe during WWII. The sky was the limit. On opportunities of getting a high end gun to add to your own collection. Especially if you were an Officer.

Now let us get to the Good General and a few of his known to be owned by guns!

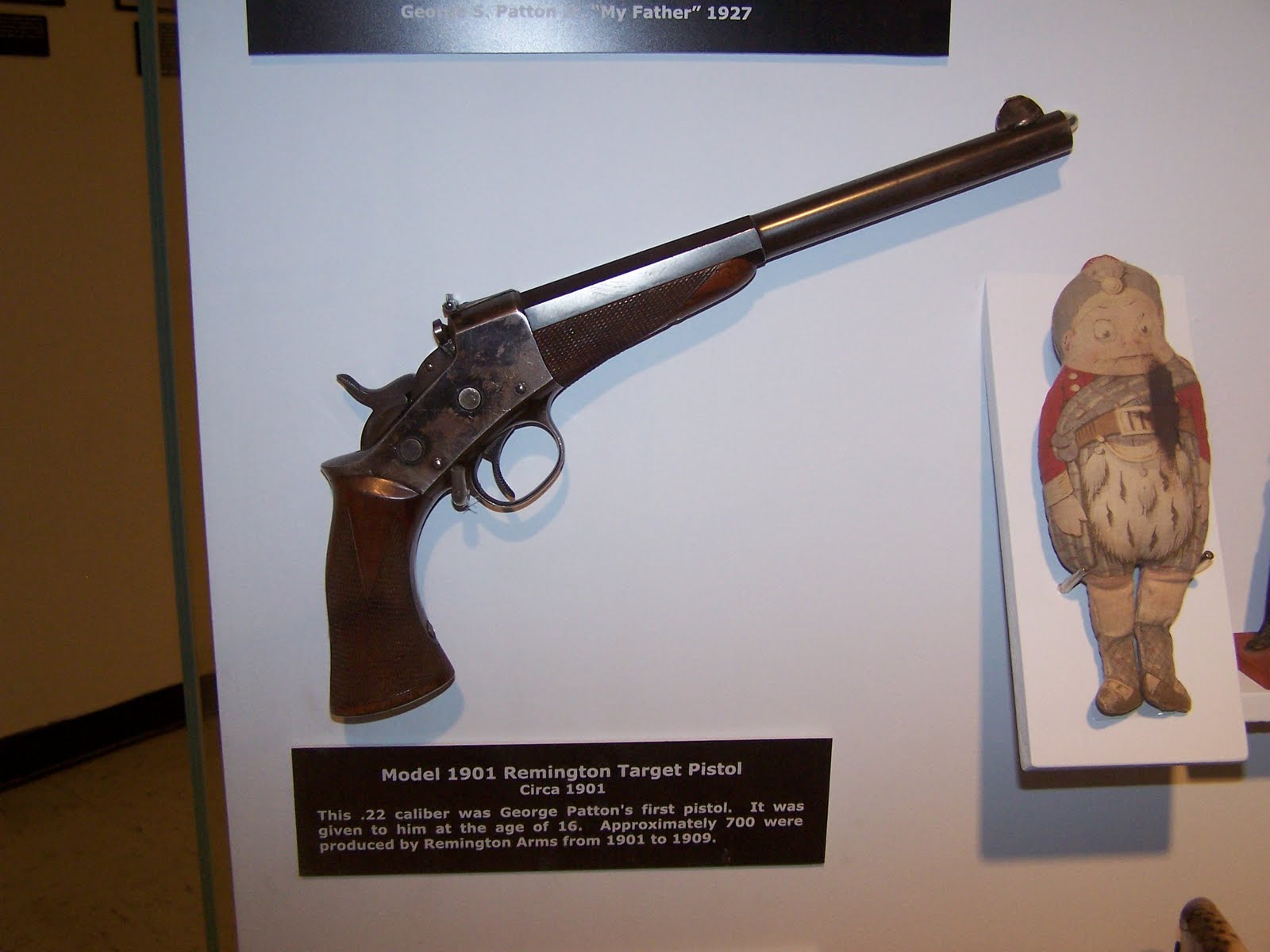

This somewhat freaky-looking 1901 Remington Target Pistol was Patton’s first pistol.

This is the famous .45 Colt Model 1873 Single-Action Army revolver, serial number 332088, purchased by George S. Patton on March 4, 1916 for $50. Its right ivory (not pearl) handle is monogrammed “GSP”, and it resides at the George Patton Museum at Fort Knox, Kentucky. – $50 equals about $4000 in today’s (2017) money. But if one considers all the engraving on it. The Old boy got his money’s worth for it.

Patton’s rig & holster.

13 Patton’s Thompson Submachine Gun

Thompson Submachine Gun of General George S. Patton Jr.Caliber: .45 ACP General Patton had this particular Thompson Submachine Gun, which he owned, in his vehicle when he was in combat areas. |

General George S. Patton with a “liberated” 18th century German Jaeger rifle .

Seems to me that somebody got himself a Mauser KAR 98 somehow.

This looks like a Colt Woodsman in his holster. While at what is called now Fort Irwin California / NTC.

Here is also another article I found that might be interesting to you. Thanks for your taking the time to read this!

Grumpy

Also do not be afraid of the PayPal service either. God am I shameless!

Here is also some other information about this Colorful Character!

Patton as a lieutenant general

|

|

| Birth name | George Smith Patton Jr. |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | “Bandito” “Old Blood and Guts” “The Old Man” |

| Born | November 11, 1885 San Gabriel, California, United States |

| Died | December 21, 1945 (aged 60) Heidelberg, Germany |

| Buried | American Cemetery and Memorial, Luxembourg City |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1909–1945 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Cavalry Branch |

| Commands held | Seventh United States Army Third United States Army Fifteenth United States Army |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross (2) Distinguished Service Medal (3) Silver Star (2) Legion of Merit Bronze Star Purple Heart Complete list of decorations |

| Relations | George Patton IV (son) John K. Waters (son-in-law) |

| Signature | |

General George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a senior officer of the United States Army who commanded the U.S. Seventh Army in the Mediterranean and European theaters of World War II, but is best known for his leadership of the U.S. Third Army in France and Germany following the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

Born in 1885 to a family with an extensive military background (with members having served in the United States Army and Confederate States Army), Patton attended the Virginia Military Institute and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He studied fencing and designed the M1913 Cavalry Saber, more commonly known as the “Patton Sword”, and partially due to his skill in the sport, he competed in the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. Patton first saw combat during the Pancho Villa Expedition in 1916, taking part in America’s first military action using motor vehicles. He later joined the newly formed United States Tank Corps of the American Expeditionary Forces and saw action in World War I, commanding the U.S. tank school in France before being wounded while leading tanks into combat near the end of the war. In the interwar period, Patton remained a central figure in the development of armored warfare doctrine in the U.S. Army, serving in numerous staff positions throughout the country. Rising through the ranks, he commanded the 2nd Armored Division at the time of the American entry into World War II.

Patton led U.S. troops into the Mediterranean theater with an invasion of Casablanca during Operation Torch in 1942, where he later established himself as an effective commander through his rapid rehabilitation of the demoralized U.S. II Corps. He commanded the U.S. Seventh Army during the Allied invasion of Sicily, where he was the first Allied commander to reach Messina. There he was embroiled in controversy after he slapped two shell-shocked soldiers under his command, and was temporarily removed from battlefield command for other duties such as participating in Operation Fortitude‘s disinformation campaign for Operation Overlord. Patton returned to command the Third Army following the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, where he led a highly successful rapid armored drive across France. He led the relief of beleaguered American troops at Bastogneduring the Battle of the Bulge, and advanced his Third Army into Nazi Germany by the end of the war.

After the war, Patton became the military governor of Bavaria, but he was relieved of this post because of his statements trivializing denazification. He commanded the United States Fifteenth Army for slightly more than two months. Patton died in Germany on December 21, 1945, as a result of injuries from an automobile accident twelve days earlier.

Patton’s colorful image, hard-driving personality and success as a commander were at times overshadowed by his controversial public statements. His philosophy of leading from the front and his ability to inspire troops with vulgarity-ridden speeches, such as a famous address to the Third Army, attracted favorable attention. His strong emphasis on rapid and aggressive offensive action proved effective. While Allied leaders held sharply differing opinions on Patton, he was regarded highly by his opponents in the German High Command. A popular, award-winning biographical film released in 1970 helped transform Patton into an American hero.

Anne Wilson “Nita” Patton, Patton’s sister. She was engaged to John J. Pershingin 1917-18.

George Smith Patton Jr. was born on November 11, 1885[1][2] in San Gabriel, California, to George Smith Patton Sr. and his wife Ruth Wilson. Patton had a younger sister, Anne, who was nicknamed “Nita”.

Patton at the Virginia Military Institute, 1907

As a child, Patton had difficulty learning to read and write, but eventually overcame this and was known in his adult life to be an avid reader.[Note 1] He was tutored from home until the age of eleven, when he was enrolled in Stephen Clark’s School for Boys, a private school in Pasadena, for six years. Patton was described as an intelligent boy and was widely read on classical military history, particularly the exploits of Hannibal, Scipio Africanus, Julius Caesar, Joan of Arc, and Napoleon Bonaparte, as well as those of family friend John Singleton Mosby, who frequently stopped by the Patton family home when George S. Patton was a child.[3] He was also a devoted horseback rider.[4]

Patton married Beatrice Banning Ayer, the daughter of Boston industrialist Frederick Ayer, on May 26, 1910 in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts. They had three children, Beatrice Smith (born March 1911), Ruth Ellen (born February 1915), and George Patton IV (born December 1923).[5]

Patton never seriously considered a career other than the military.[4] At the age of seventeen he sought an appointment to the United States Military Academy. Patton applied to several universities with Reserve Officer’s Training Corps programs. Patton was accepted to Princeton College but eventually decided on VMI, which his father and grandfather had attended.[6] He attended the school from 1903 to 1904 and, though he struggled with reading and writing, performed exceptionally in uniform and appearance inspection as well as military drill. While Patton was at VMI, California’s Senator nominated him for West Point.[7]

In his plebe (first) year at West Point, Patton adjusted easily to the routine. However, his academic performance was so poor that he was forced to repeat his first year after failing mathematics.[8] Patton excelled at military drills though his academic performance remained average. He was cadet sergeant major his junior year, and cadet adjutant his senior year. He also joined the football team but injured his arm and ceased playing on several occasions, instead trying out for the sword team and track and field,[9] quickly becoming one of the best swordsmen at the academy.[10] Ranked 46 out of 103, Patton graduated from West Point on June 11, 1909 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Cavalry Branch of the United States Army.[11][12]

The Patton family was of Irish, Scots-Irish, English, and Welsh ancestry. His great-grandmother came from an aristocratic Welsh family, descended from many Welsh lords of Glamorgan,[4] which had an extensive military background. Patton believed he had former lives as a soldier and took pride in mystical ties with his ancestors.[13][14][15][16] Though not directly descended from George Washington, Patton traced some of his English colonial roots to George Washington’s great-grandfather.[17][18] He was also descended from England’s King Edward I through Edward’s son Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent.[17][18] Family belief held the Pattons were descended from sixteen barons who had signed the Magna Carta.[19] Patton believed in reincarnation, and his ancestry was very important to him, forming a central part of his personal identity.[20] The first Patton in America was Robert Patton, born in Ayr, Scotland. He emigrated to Culpeper, Virginia, from Glasgow, in either 1769 or 1770.[21] His paternal grandfather was George Smith Patton, who commanded the 22nd Virginia Infantry under Jubal Early in the Civil War and was killed in the Third Battle of Winchester, while his great-uncle Waller T. Patton was killed in Pickett’s Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg. Patton also descended from Hugh Mercer, who had been killed in the Battle of Princeton during the American Revolution. Patton’s father graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), became a lawyer and later the district attorney of Los Angeles County. Patton’s maternal grandfather was Benjamin Davis Wilson, a merchant who had been the second Mayor of Los Angeles. His father was a wealthy rancher and lawyer who owned a thousand-acre ranch near Pasadena, California.[22][23] Patton is also a descendant of French Huguenot Louis DuBois. [24] [25]

Patton’s first posting was with the 15th Cavalry at Fort Sheridan, Illinois,[26] where he established himself as a hard-driving leader who impressed superiors with his dedication.[27] In late 1911, Patton was transferred to Fort Myer, Virginia, where many of the Army’s senior leaders were stationed. Befriending Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, Patton served as his aide at social functions on top of his regular duties as quartermaster for his troop.[28]

Patton (at right) fencing in the modern pentathlon of the 1912 Summer Olympics

For his skill with running and fencing, Patton was selected as the Army’s entry for the first modern pentathlon at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden.[29] Of 42 competitors, Patton placed twenty-first on the pistol range, seventh in swimming, fourth in fencing, sixth in the equestrian competition, and third in the footrace, finishing fifth overall and first among the non-Swedish competitors.[30] There was some controversy concerning his performance in the pistol shooting competition, where he used a .38 caliber pistol while most of the other competitors chose .22 caliber firearms. He claimed that the holes in the paper from his early shots were so large that some of his later bullets passed through them, but the judges decided he missed the target completely once. Modern competitions on this level frequently now employ a moving background to specifically track multiple shots through the same hole.[31][32] If his assertion was correct, Patton would likely have won an Olympic medal in the event.[33] The judges’ ruling was upheld. Patton’s only comment on the matter was:

The high spirit of sportsmanship and generosity manifested throughout speaks volumes for the character of the officers of the present day. There was not a single incident of a protest or any unsportsmanlike quibbling or fighting for points which I may say, marred some of the other civilian competitions at the Olympic Games. Each man did his best and took what fortune sent them like a true soldier, and at the end we all felt more like good friends and comrades than rivals in a severe competition, yet this spirit of friendship in no manner detracted from the zeal with which all strove for success.[31]

Following the 1912 Olympics, Patton traveled to Saumur, France, where he learned fencing techniques from Adjutant Charles Cléry, a French “master of arms” and instructor of fencing at the cavalry school there.[34] Bringing these lessons back to Fort Myer, Patton redesigned saber combat doctrine for the U.S. cavalry, favoring thrusting attacks over the standard slashing maneuver and designing a new sword for such attacks. He was temporarily assigned to the Office of the Army Chief of Staff, and in 1913, the first 20,000 of the Model 1913 Cavalry Saber—popularly known as the “Patton sword”—were ordered. Patton then returned to Saumur to learn advanced techniques before bringing his skills to the Mounted Service School at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he would be both a student and a fencing instructor. He was the first Army officer to be designated “Master of the Sword”,[35][36] a title denoting the school’s top instructor in swordsmanship.[37]Arriving in September 1913, he taught fencing to other cavalry officers, many of whom were senior to him in rank.[38]Patton graduated from this school in June 1915. He was originally intended to return to the 15th Cavalry,[39] which was bound for the Philippines. Fearing this assignment would dead-end his career, Patton traveled to Washington, D.C. during 11 days of leave and convinced influential friends to arrange a reassignment for him to the 8th Cavalry at Fort Bliss, Texas, anticipating that instability in Mexico might boil over into a full-scale civil war.[40] In the meantime, Patton was selected to participate in the 1916 Summer Olympics, but that olympiad was cancelled due to World War I.[41]

1915 Dodge Brothers Model 30-35 touring car. This model from the new Dodge Brothers company won some renown for its durability because of its use in the 1916 Pancho Villa Expedition.[42]

In 1915 Patton was assigned to border patrol duty with A Company of the 8th Cavalry, based in Sierra Blanca.[43][44] During his time in the town, Patton took to wearing his M1911 Colt .45 in his belt rather than a holster. His firearm discharged accidentally one night in a saloon, so he swapped it for an ivory-handled Colt Single Action Army revolver, a weapon that would later become an icon of Patton’s image.[45]

In March 1916 Mexican forces loyal to Pancho Villa crossed into New Mexico and raided the border town of Columbus. The violence in Columbus killed several Americans. In response, the U.S. launched the Pancho Villa Expedition into Mexico. Chagrined to discover that his unit would not participate, Patton appealed to expedition commander John J. Pershing, and was named his personal aide for the expedition. This meant that Patton would have some role in organizing the effort, and his eagerness and dedication to the task impressed Pershing.[46][47]Patton modeled much of his leadership style after Pershing, who favored strong, decisive actions and commanding from the front.[48][49] As an aide, Patton oversaw the logistics of Pershing’s transportation and acted as his personal courier.[50]

In mid-April, Patton asked Pershing for the opportunity to command troops, and was assigned to Troop C of the 13th Cavalry to assist in the manhunt for Villa and his subordinates.[51] His initial combat experience came on May 14, 1916 in what would become the first motorized attack in the history of U.S. warfare. A force under his command of ten soldiers and two civilian guides with the 6th Infantry in three Dodge touring cars surprised three of Villa’s men during a foraging expedition, killing Julio Cárdenas and two of his guards.[47][52] It was not clear if Patton personally killed any of the men, but he was known to have wounded all three.[53] The incident garnered Patton both Pershing’s good favor and widespread media attention as a “bandit killer”.[47][54] Shortly after, he was promoted to first lieutenant while a part of the 10th Cavalry on May 23, 1916.[43] Patton remained in Mexico until the end of the year. President Woodrow Wilson forbade the expedition from conducting aggressive patrols deeper into Mexico, so it remained encamped in the Mexican border states for much of that time. In October Patton briefly retired to California after being burned by an exploding gas lamp.[55] He returned from the expedition permanently in February 1917.[56]

Patton at Bourg in France in 1918 with a Renault FT light tank

After the Villa Expedition, Patton was detailed to Front Royal, Virginia, to oversee horse procurement for the Army, but Pershing intervened on his behalf.[56] After the United States entered World War I, and Pershing was named commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) on the Western Front, Patton requested to join his staff.[47] Patton was promoted to captain on May 15, 1917 and left for Europe, among the 180 men of Pershing’s advance party which departed May 28 and arrived in Liverpool, England, on June 8.[57] Taken as Pershing’s personal aide, Patton oversaw the training of American troops in Paris until September, then moved to Chaumont and assigned as a post adjutant, commanding the headquarters company overseeing the base. Patton was dissatisfied with the post and began to take an interest in tanks, as Pershing sought to give him command of an infantry battalion.[58] While in a hospital for jaundice, Patton met Colonel Fox Conner, who encouraged him to work with tanks instead of infantry.[59]

On November 10, 1917 Patton was assigned to establish the AEF Light Tank School.[47] He left Paris and reported to the French Army‘s tank training school at Champlieu near Orrouy, where he drove a Renault FT light tank. On November 20, the British launched an offensive towards the important rail center of Cambrai, using an unprecedented number of tanks.[60] At the conclusion of his tour on December 1, Patton went to Albert, 30 miles (48 km) from Cambrai, to be briefed on the results of this attack by the chief of staff of the British Tank Corps, Colonel J. F. C. Fuller.[61] On the way back to Paris, he visited the Renault factory to observe the tanks being manufactured. Patton was promoted to major on January 26, 1918.[59] He received the first ten tanks on March 23, 1918 at the Tank School at Bourg, a small village close to Langres, Haute-Marne département. The only US soldier with tank-driving experience, Patton personally backed seven of the tanks off the train.[62] In the post, Patton trained tank crews to operate in support of infantry, and promoted its acceptance among reluctant infantry officers.[63] He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on April 3, 1918, and attended the Command and General Staff College in Langres.[64]

In August 1918, he was placed in charge of the U.S. 1st Provisional Tank Brigade (re-designated the 304th Tank Brigadeon November 6, 1918). Patton’s Light Tank Brigade was part of Colonel Samuel Rockenbach‘s Tank Corps, part of the American First Army.[65] Personally overseeing the logistics of the tanks in their first combat use by U.S. forces, and reconnoitering the target area for their first attack himself, Patton ordered that no U.S. tank be surrendered.[64][66] Patton commanded American-crewed Renault FT tanks at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel,[67] leading the tanks from the front for much of their attack, which began on September 12. He walked in front of the tanks into the German-held village of Essey, and rode on top of a tank during the attack into Pannes, seeking to inspire his men.[68]

Patton’s brigade was then moved to support U.S. I Corps in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 26.[67] He personally led a troop of tanks through thick fog as they advanced 5 miles (8 km) into German lines. Around 09:00, Patton was wounded while leading six men and a tank in an attack on German machine guns near the town of Cheppy.[69][70] His orderly, Private First Class Joe Angelo, saved Patton, for which he was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[71]Patton commanded the battle from a shell hole for another hour before being evacuated. He stopped at a rear command post to submit his report before heading to a hospital. Sereno E. Brett, commander of the U.S. 326th Tank Battalion, took command of the brigade in Patton’s absence. Patton wrote in a letter to his wife: “The bullet went into the front of my left leg and came out just at the crack of my bottom about two inches to the left of my rectum. It was fired at about 50 m so made a hole about the size of a [silver] dollar where it came out.”[72]

While recuperating from his wound, Patton was promoted to colonel in the Tank Corps of the U.S. National Army on October 17. He returned to duty on October 28 but saw no further action before hostilities ended with the armistice of November 11, 1918.[73] For his actions in Cheppy, Patton received the Distinguished Service Cross. For his leadership of the brigade and tank school, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. He was also awarded the Purple Heart for his combat wounds after the decoration was created in 1932.[74]

Patton as a temporary colonel at Camp Meade, Maryland, 1919

Patton left France for New York City on March 2, 1919. After the war he was assigned to Camp Meade, Maryland, and reverted to his permanent rank of captain on June 30, 1920, though he was promoted to major again the next day. Patton was given temporary duty in Washington D.C. that year to serve on a committee writing a manual on tank operations. During this time he developed a belief that tanks should be used not as infantry support, but rather as an independent fighting force. Patton supported the M1919 tank design created by J. Walter Christie, a project which was shelved due to financial considerations.[75]While on duty in Washington, D.C., in 1919, Patton met Dwight D. Eisenhower,[76]who would play an enormous role in Patton’s future career. During and following Patton’s assignment in Hawaii, he and Eisenhower corresponded frequently. Patton sent Eisenhower notes and assistance to help him graduate from the General Staff College.[77] With Christie, Eisenhower, and a handful of other officers, Patton pushed for more development of armored warfare in the interwar era. These thoughts resonated with Secretary of War Dwight Davis, but the limited military budget and prevalence of already-established Infantry and Cavalry branches meant the U.S. would not develop its armored corps much until 1940.[78]

On September 30, 1920, Patton relinquished command of the 304th Tank Brigade and was reassigned to Fort Myer as commander of 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry.[77] Loathing duty as a peacetime staff officer, he spent much time writing technical papers and giving speeches on his combat experiences at the General Staff College.[75] In July 1921 Patton became a member of the American Legion Tank Corps Post No. 19.[79] From 1922 to mid-1923 he attended the Field Officer’s Course at the Cavalry School at Fort Riley, then he attended the Command and General Staff College from mid-1923 to mid-1924,[77] graduating 25th out of 248.[80] In August 1923, Patton saved several children from drowning when they fell off a yacht during a boating trip off Salem, Massachusetts. He was awarded the Silver Lifesaving Medal for this action.[81] He was temporarily appointed to the General Staff Corps in Boston, Massachusetts, before being reassigned as G-1 and G-2 of the Hawaiian Division at Schofield Barracks in Honolulu in March 1925.[77]

Patton was made G-3 of the Hawaiian Division for several months, before being transferred in May 1927 to the Office of the Chief of Cavalry in Washington, D.C., where he began to develop the concepts of mechanized warfare. A short-lived experiment to merge infantry, cavalry and artillery into a combined arms force was cancelled after U.S. Congress removed funding. Patton left this office in 1931, returned to Massachusetts and attended the Army War College, becoming a “Distinguished Graduate” in June 1932.[82]

In July 1932, Patton was executive officer of the 3rd Cavalry, which was ordered to Washington by Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur. Patton took command of the 600 troops of the 3rd Cavalry, and on July 28, MacArthur ordered Patton’s troops to advance on protesting veterans known as the “Bonus Army” with tear gas and bayonets. Patton was dissatisfied with MacArthur’s conduct, as he recognized the legitimacy of the veterans’ complaints and had himself earlier refused to issue the order to employ armed force to disperse the veterans. Patton later stated that, though he found the duty “most distasteful”, he also felt that putting the marchers down prevented an insurrection and saved lives and property. He personally led the 3rd Cavalry down Pennsylvania Avenue, dispersing the protesters.[83][84] Patton also encountered his former orderly as one of the marchers and forcibly ordered him away, fearing such a meeting might make the headlines.[85]

Patton was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the regular Army on March 1, 1934, and was transferred to the Hawaiian Division in early 1935 to serve as G-2. Patton followed the growing hostility and conquest aspirations of the militant Japanese leadership. He wrote a plan to intern the Japanese living in the islands in the event of an attack as a result of the atrocities carried out by Japanese soldiers on the Chinese in the Sino-Japanese war. In 1937 he wrote a paper with the title “Surprise” which predicted, with what D’Este termed “chilling accuracy”, a surprise attack by the Japanese on Hawaii.[86] Depressed at the lack of prospects for new conflict, Patton took to drinking heavily and began a brief affair with his 21-year-old niece by marriage, Jean Gordon.[87]

Patton continued playing polo and sailing in this time. After sailing back to Los Angeles for extended leave in 1937, he was kicked by a horse and fractured his leg. Patton developed phlebitis from the injury, which nearly killed him. The incident almost forced Patton out of active service, but a six-month administrative assignment in the Academic Department at the Cavalry School at Fort Riley helped him to recover.[87] Patton was promoted to colonel on July 24, 1938 and given command of the 5th Cavalry at Fort Clark, Texas, for six months, a post he relished, but he was reassigned to Fort Myer again in December as commander of the 3rd Cavalry. There, he met Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, who was so impressed with him that Marshall considered Patton a prime candidate for promotion to general. In peacetime, though, he would remain a colonel to remain eligible to command a regiment.[88]

Patton had a personal schooner named When and If. The schooner was designed by famous naval architect John G. Alden and built in 1939. The schooner’s name comes from Patton saying he would sail it “when and if” he returned from war.[89]

Following the German Army‘s invasion of Poland and the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, the U.S. military entered a period of mobilization, and Patton sought to build up the power of U.S. armored forces. During maneuvers the Third Army conducted in 1940, Patton served as an umpire, where he met Adna R. Chaffee Jr. and the two formulated recommendations to develop an armored force. Chaffee was named commander of this force,[90] and created the 1st and 2nd Armored Divisions as well as the first combined arms doctrine. He named Patton commander of the 2nd Armored Brigade, part of the 2nd Armored Division. The division was one of few organized as a heavy formation with many tanks, and Patton was in charge of its training.[91] Patton was promoted to brigadier general on October 2, made acting division commander in November, and on April 4, 1941 was promoted again to major general and made Commanding General (CG) of the 2nd Armored Division.[90] As Chaffee stepped down from command of the I Armored Corps, Patton became the most prominent figure in U.S. armor doctrine. In December 1940, he staged a high-profile mass exercise in which 1,000 tanks and vehicles were driven from Columbus, Georgia, to Panama City, Florida, and back.[92]He repeated the exercise with his entire division of 1,300 vehicles the next month.[93] Patton earned a pilot’s license and, during these maneuvers, observed the movements of his vehicles from the air to find ways to deploy them effectively in combat.[92] His exploits earned him a spot on the cover of Life Magazine.[94]

Patton led the division during the Tennessee Maneuvers in June 1941, and was lauded for his leadership, executing 48 hours’ worth of planned objectives in only nine. During the September Louisiana Maneuvers, his division was part of the losing Red Army in Phase I, but in Phase II was assigned to the Blue Army. His division executed a 400-mile (640 km) end run around the Red Army and “captured” Shreveport, Louisiana. During the October–November Carolina Maneuvers, Patton’s division captured Hugh Drum, commander of the opposing army.[95] On January 15, 1942 he was given command of I Armored Corps, and the next month established the Desert Training Center[96] in the Imperial Valley to run training exercises. He commenced these exercises in late 1941 and continued them into the summer of 1942. Patton chose a 10,000-acre (40 km2) expanse of desert area about 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Palm Springs.[97] From his first days as a commander, Patton strongly emphasized the need for armored forces to stay in constant contact with opposing forces. His instinctive preference for offensive movement was typified by an answer Patton gave to war correspondents in a 1944 press conference. In response to a question on whether the Third Army’s rapid offensive across France should be slowed to reduce the number of U.S. casualties, Patton replied, “Whenever you slow anything down, you waste human lives.”[98] It was around this time that a reporter, after hearing a speech where Patton said that it took “blood and brains” to win in combat, began calling him “blood and guts”. The nickname would follow him for the rest of his life.[99] Soldiers under his command were known at times to have quipped, “our blood, his guts”. Nonetheless, he was known to be admired widely by the men under his charge.[100] Patton was also known simply as “The Old Man” among his troops.[101]

Patton (left) with Rear AdmiralHenry Kent Hewitt aboard USS Augusta, off the coast of North Africa, November 1942

Under Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, Patton was assigned to help plan the Allied invasion of French North Africa as part of Operation Torch in the summer of 1942.[102][103] Patton commanded the Western Task Force, consisting of 33,000 men in 100 ships, in landings centered on Casablanca, Morocco. The landings, which took place on November 8, 1942, were opposed by Vichy French forces, but Patton’s men quickly gained a beachhead and pushed through fierce resistance. Casablanca fell on November 11 and Patton negotiated an armistice with French General Charles Noguès.[104][105] The Sultan of Morocco was so impressed that he presented Patton with the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, with the citation “Les Lions dans leurs tanières tremblent en le voyant approcher” (The lions in their dens tremble at his approach).[106] Patton oversaw the conversion of Casablanca into a military port and hosted the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.[107]

On March 6, 1943, following the defeat of the U.S. II Corps by the German Afrika Korps, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, at the Battle of Kasserine Pass, Patton replaced Major General Lloyd Fredendall as Commanding General of the II Corps and was promoted to lieutenant general. Soon thereafter, he had Major General Omar Bradley reassigned to his corps as its deputy commander.[108] With orders to take the battered and demoralized formation into action in 10 days’ time, Patton immediately introduced sweeping changes, ordering all soldiers to wear clean, pressed and complete uniforms, establishing rigorous schedules, and requiring strict adherence to military protocol. He continuously moved throughout the command talking with men, seeking to shape them into effective soldiers. He pushed them hard, and sought to reward them well for their accomplishments.[109] His uncompromising leadership style is evidenced by his orders for an attack on a hill position near Gafsa which are reported to have ended “I expect to see such casualties among officers, particularly staff officers, as will convince me that a serious effort has been made to capture this objective.”[110]

Patton’s training was effective, and on March 17, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division took Gafsa, winning the Battle of El Guettar, and pushing a German and Italian armored force back twice. In the meantime, on April 5, he removed Major General Orlando Ward, commanding the 1st Armored Division, after its lackluster performance at Maknassy against numerically inferior German forces. Advancing on Gabès, Patton’s corps pressured the Mareth Line.[109] During this time, he reported to British General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 18th Army Group, and came into conflict with Air Vice MarshalSir Arthur Coningham about the lack of close air support being provided for his troops. When Coningham dispatched three officers to Patton’s headquarters to persuade him that the British were providing ample air support, they came under German air attack mid-meeting, and part of the ceiling of Patton’s office collapsed around them. Speaking later of the German pilots who had struck, Patton remarked, “if I could find the sons of bitches who flew those planes, I’d mail each of them a medal.”[111] By the time his force reached Gabès, the Germans had abandoned it. He then relinquished command of II Corps to Bradley, and returned to the I Armored Corps in Casablanca to help plan Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Fearing U.S. troops would be sidelined, he convinced British commanders to allow them to continue fighting through to the end of the Tunisia Campaign before leaving on this new assignment.[111][112]

For Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, Patton was to command the Seventh United States Army, dubbed the Western Task Force, in landings at Gela, Scoglitti and Licata to support landings by Bernard Montgomery‘s British Eighth Army. Patton’s I Armored Corps was officially redesignated the Seventh Army just before his force of 90,000 landed before dawn on D-Day, July 10, 1943, on beaches near the town of Licata. The armada was hampered by wind and weather, but despite this the three U.S. infantry divisions involved, the 3rd, 1st, and 45th, secured their respective beaches. They then repulsed counterattacks at Gela,[113] where Patton personally led his troops against German reinforcements from the Hermann Göring Division.[114]

Initially ordered to protect the British forces’ left flank, Patton was granted permission by Alexander to take Palermo after Montgomery’s forces became bogged down on the road to Messina. As part of a provisional corps under Major General Geoffrey Keyes, the 3rd Infantry Division under Major General Lucian Truscott covered 100 miles (160 km) in 72 hours, arriving at Palermo on July 21. He then set his sights on Messina.[115] He sought an amphibious assault, but it was delayed by lack of landing craft, and his troops did not land at Santo Stefanountil August 8, by which time the Germans and Italians had already evacuated the bulk of their troops to mainland Italy. He ordered more landings on August 10 by the 3rd Infantry Division, which took heavy casualties but pushed the German forces back, and hastened the advance on Messina.[116] A third landing was completed on August 16, and by 22:00 that day Messina fell to his forces. By the end of the battle, the 200,000-man Seventh Army had suffered 7,500 casualties, and killed or captured 113,000 Axis troops and destroyed 3,500 vehicles. Still, 40,000 German and 70,000 Italian troops escaped to Italy with 10,000 vehicles.[117][118]

Patton’s conduct in this campaign met with several controversies. When Alexander sent a transmission on July 19 limiting Patton’s attack on Messina, his chief of staff, Brigadier General Hobart R. Gay, claimed the message was “lost in transmission” until Messina had fallen. On July 22 he shot and killed a pair of mules that had stopped while pulling a cart across a bridge. The cart was blocking the way of a U.S. armored column which was under attack from German aircraft. When their Sicilian owner protested, Patton attacked him with a walking stick and pushed the two mules off of the bridge.[115] When informed of the massacre of Italian prisoners at Biscari by troops under his command, Patton wrote in his diary, “I told Bradley that it was probably an exaggeration, but in any case to tell the officer to certify that the dead men were snipers or had attempted to escape or something, as it would make a stink in the press and also would make the civilians mad. Anyhow, they are dead, so nothing can be done about it.”[119] Bradley refused Patton’s suggestions. Patton later changed his mind. After he learned that the 45th Division’s Inspector General found “no provocation on the part of the prisoners … They had been slaughtered” Patton is reported to have said: “Try the bastards.”[119] Patton also came into frequent disagreements with Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. and Theodore Roosevelt Jr. and acquiesced to their relief by Bradley.[120]

Two high-profile incidents of Patton striking subordinates during the Sicily campaign attracted national controversy following the end of the campaign. On August 3, 1943, Patton slapped and verbally abused Private Charles H. Kuhl at an evacuation hospital in Nicosia after he had been found to suffer from “battle fatigue“.[121] On August 10, Patton slapped Private Paul G. Bennett under similar circumstances.[121] Ordering both soldiers back to the front lines,[122] Patton railed against cowardice and issued orders to his commanders to discipline any soldier making similar complaints.[123]

Word of the incident reached Eisenhower, who privately reprimanded Patton and insisted he apologize.[124] Patton apologized to both soldiers individually, as well as to doctors who witnessed the incidents,[125] and later to all of the soldiers under his command in several speeches.[126] Eisenhower suppressed the incident in the media,[127] but in November journalist Drew Pearson revealed it on his radio program.[128] Criticism of Patton in the United States was harsh, and included members of Congress and former generals, Pershing among them.[129][130] The views of the general public remained mixed on the matter,[131] and eventually Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson stated that Patton must be retained as a commander because of the need for his “aggressive, winning leadership in the bitter battles which are to come before final victory.”[132]

Patton did not command a force in combat for 11 months.[133] In September, Bradley, who was Patton’s junior in both rank and experience, was selected to command the First United States Army forming in England to prepare for Operation Overlord.[134] This decision had been made before the slapping incidents were made public, but Patton blamed them for his being denied the command.[135] Eisenhower felt the invasion of Europe was too important to risk any uncertainty, and that the slapping incidents had been an example of Patton’s inability to exercise discipline and self-control. While Eisenhower and Marshall both considered Patton to be a skilled combat commander, they felt Bradley was less impulsive or prone to making mistakes.[136] On January 26, 1944 Patton was formally given command of the Third United States Army in England, a newly arrived unit, and assigned to prepare its inexperienced soldiers for combat in Europe.[137][138]This duty kept Patton busy in early 1944 preparing for the pending invasion.[139]

The German High Command had more respect for Patton than for any other Allied commander and considered him central to any plan to invade Europe from the United Kingdom.[140] Because of this, Patton was made a prominent figure in the deception operation, Fortitude, in early 1944.[141] Through the British network of double-agents, the Allies fed German intelligence a steady stream of false reports about troops sightings and that Patton had been named commander of the First United States Army Group (FUSAG), all designed to convince the Germans that Patton was preparing this massive command for an invasion at Pas de Calais. FUSAG was in reality an intricately constructed “phantom” army of decoys, props, and fake signals traffic based around Dover to mislead German aircraft and to make Axis leaders believe a large force was massing there so as to mask the real location of the invasion in Normandy. Patton was ordered to keep a low profile to deceive the Germans into thinking he was in Dover throughout early 1944, when he was actually training the Third Army.[140] As a result of Operation Fortitude, the German 15th Army remained at Pas de Calais to defend against Patton’s supposed attack.[142] This formation held its position even after the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Patton flew into France a month later and returned to combat duty.[143]

Sailing to Normandy throughout July, Patton’s Third Army formed on the extreme right (west) of the Allied land forces,[143][Note 2] and became operational at noon on August 1, 1944, under Bradley’s Twelfth United States Army Group. The Third Army simultaneously attacked west into Brittany, south, east toward the Seine, and north, assisting in trapping several hundred thousand German soldiers in the Falaise Pocket between Falaise and Argentan.[145][146]

Patton’s strategy with his army favored speed and aggressive offensive action, though his forces saw less opposition than did the other three Allied field armies in the initial weeks of its advance.[147] The Third Army typically employed forward scout units to determine enemy strength and positions. Self-propelled artillery moved with the spearhead units and was sited well forward, ready to engage protected German positions with indirect fire. Light aircraft such as the Piper L-4 Cubserved as artillery spotters and provided airborne reconnaissance. Once located, the armored infantry would attack using tanks as infantry support. Other armored units would then break through enemy lines and exploit any subsequent breach, constantly pressuring withdrawing German forces to prevent them from regrouping and reforming a cohesive defensive line.[148] The U.S. armor advanced using reconnaissance by fire, and the .50 caliber M2 Browning heavy machine gun proved effective in this role, often flushing out and killing German panzerfaust teams waiting in ambush as well as breaking up German infantry assaults against the armored infantry.[149]

The speed of the advance forced Patton’s units to rely heavily on air reconnaissance and tactical air support.[148] The Third Army had by far more military intelligence (G-2) officers at headquarters specifically designated to coordinate air strikes than any other army.[150] Its attached close air support group was XIX Tactical Air Command, commanded by Brigadier General Otto P. Weyland. Developed originally by General Elwood Quesada of IX Tactical Air Command for the First Army in Operation Cobra, the technique of “armored column cover”, in which close air support was directed by an air traffic controller in one of the attacking tanks, was used extensively by the Third Army. Each column was protected by a standing patrol of three to four P-47 and P-51 fighter-bombers as a combat air patrol (CAP).[151]

In its advance from Avranches to Argentan, the Third Army traversed 60 miles (97 km) in just two weeks. Patton’s force was supplemented by Ultra intelligence for which he was briefed daily by his G-2, Colonel Oscar W. Koch, who apprised him of German counterattacks, and where to concentrate his forces.[152] Equally important to the advance of Third Army columns in northern France was the rapid advance of the supply echelons. Third Army logistics were overseen by Colonel Walter J. Muller, Patton’s G-4, who emphasized flexibility, improvisation, and adaptation for Third Army supply echelons so forward units could rapidly exploit a breakthrough. Patton’s rapid drive to Lorraine demonstrated his keen appreciation for the technological advantages of the U.S. Army. The major U.S. and Allied advantages were in mobility and air superiority. The U.S. Army had more trucks, more reliable tanks, and better radio communications, all of which contributed to a superior ability to operate at a rapid offensive pace.[153]

Patton pins a Silver Star Medal on Private Ernest A. Jenkins, a soldier under his command, October 1944.

Patton’s offensive came to a halt on August 31, 1944, as the Third Army ran out of fuel near the Moselle River, just outside Metz. Patton expected that the theater commander would keep fuel and supplies flowing to support successful advances, but Eisenhower favored a “broad front” approach to the ground-war effort, believing that a single thrust would have to drop off flank protection, and would quickly lose its punch. Still within the constraints of a very large effort overall, Eisenhower gave Montgomery and his Twenty First Army Group a higher priority for supplies for Operation Market Garden.[154]Combined with other demands on the limited resource pool, this resulted in the Third Army exhausting its fuel supplies.[155] Patton believed his forces were close enough to the Siegfried Line that he remarked to Bradley that with 400,000 gallons of gasoline he could be in Germany within two days.[156] In late September, a large German Panzer counterattack sent expressly to stop the advance of Patton’s Third Army was defeated by the U.S. 4th Armored Division at the Battle of Arracourt. Despite the victory, the Third Army stayed in place as a result of Eisenhower’s order. The German commanders believed this was because their counterattack had been successful.[157]

The halt of the Third Army during the month of September was enough to allow the Germans to strengthen the fortress of Metz. In October and November, the Third Army was mired in a near-stalemate with the Germans during the Battle of Metz, both sides suffering heavy casualties. An attemptby Patton to seize Fort Driant just south of Metz was defeated, but by mid-November Metz had fallen to the Americans.[158] Patton’s decisions in taking this city were criticized. German commanders interviewed after the war noted he could have bypassed the city and moved north to Luxembourg where he would have been able to cut off the German Seventh Army.[159] The German commander of Metz, General Hermann Balck, also noted that a more direct attack would have resulted in a more decisive Allied victory in the city. Historian Carlo D’Este later wrote that the Lorraine Campaign was one of Patton’s least successful, faulting him for not deploying his divisions more aggressively and decisively.[160]

With supplies low and priority given to Montgomery until the port of Antwerp could be opened, Patton remained frustrated at the lack of progress of his forces. From November 8 to December 15, his army advanced no more than 40 miles (64 km).[161]

Bradley, Eisenhower and Patton in Europe, 1945

In December 1944, the German army, under the command of German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, launched a last-ditch offensive across Belgium, Luxembourg, and northeastern France. On December 16, 1944, it massed 29 divisions totaling 250,000 men at a weak point in the Allied lines, and during the early stages of the ensuing Battle of the Bulge, made significant headway towards the Meuse River during the worst winter Europe had seen in years. Eisenhower called a meeting of all senior Allied commanders on the Western Front to a headquarters near Verdun on the morning of December 19 to plan strategy and a response to the German assault.[162]

At the time, Patton’s Third Army was engaged in heavy fighting near Saarbrücken. Guessing the intent of the Allied command meeting, Patton ordered his staff to make three separate operational contingency orders to disengage elements of the Third Army from its present position and begin offensive operations toward several objectives in the area of the bulge occupied by German forces.[163] At the Supreme Command conference, Eisenhower led the meeting, which was attended by Patton, Bradley, General Jacob Devers, Major General Kenneth Strong, Deputy Supreme Commander Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, and several staff officers.[164] When Eisenhower asked Patton how long it would take him to disengage six divisions of his Third Army and commence a counterattack north to relieve the U.S. 101st Airborne Division which had been trapped at Bastogne, Patton replied, “As soon as you’re through with me.”[165] Patton then clarified that he had already worked up an operational order for a counterattack by three full divisions on December 21, then only 48 hours away.[165] Eisenhower was incredulous: “Don’t be fatuous, George. If you try to go that early you won’t have all three divisions ready and you’ll go piecemeal.” Patton replied that his staff already had a contingency operations order ready to go. Still unconvinced, Eisenhower ordered Patton to attack the morning of December 22, using at least three divisions.[166]

Patton left the conference room, phoned his command, and uttered two words: “Play ball.” This code phrase initiated a prearranged operational order with Patton’s staff, mobilizing three divisions – the 4th Armored Division, the U.S. 80th Infantry Division, and the U.S. 26th Infantry Division – from the Third Army and moving them north toward Bastogne.[163]In all, Patton would reposition six full divisions, U.S. III Corps and U.S. XII Corps, from their positions on the Saar Riverfront along a line stretching from Bastogne to Diekirch and to Echternach, the town in Luxembourg that had been at the southern end of the initial “Bulge” front line on December 16.[167] Within a few days, more than 133,000 Third Army vehicles were re-routed into an offensive that covered an average distance of over 11 miles (18 km) per vehicle, followed by support echelons carrying 62,000 tonnes (61,000 long tons; 68,000 short tons) of supplies.[168]

On December 21, Patton met with Bradley to review the impending advance, starting the meeting by remarking, “Brad, this time the Kraut’s stuck his head in the meat grinder, and I’ve got hold of the handle.”[163] Patton then argued that his Third Army should attack toward Koblenz, cutting off the bulge at the base and trap the entirety of the German armies involved in the offensive. After briefly considering this, Bradley vetoed this proposal, as he was less concerned about killing large numbers of Germans than he was in arranging for the relief of Bastogne before it was overrun.[166] Desiring good weather for his advance, which would permit close ground support by U.S. Army Air Forces tactical aircraft, Patton ordered the Third Army chaplain, Colonel James Hugh O’Neill, to compose a suitable prayer:

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies, and establish Thy justice among men and nations. Amen.[127]

When the weather cleared soon after, Patton awarded O’Neill a Bronze Star Medal on the spot.[127]

On December 26, 1944, the first spearhead units of the Third Army’s 4th Armored Division reached Bastogne, opening a corridor for relief and resupply of the besieged forces. Patton’s ability to disengage six divisions from front line combat during the middle of winter, then wheel north to relieve Bastogne was one of his most remarkable achievements during the war.[169] He later wrote that the relief of Bastogne was “the most brilliant operation we have thus far performed, and it is in my opinion the outstanding achievement of the war. This is my biggest battle.”[168]

By February, the Germans were in full retreat. On February 23, 1945, the U.S. 94th Infantry Division crossed the Saar and established a vital bridgehead at Serrig through which Patton pushed units into the Saarland. Patton had insisted upon an immediate crossing of the Saar River against the advice of his officers. Historians such as Charles Whiting have criticized this strategy as unnecessarily aggressive.[170]

Once again, Patton found other commands given priority on gasoline and supplies.[171] To obtain these, Third Army ordnance units passed themselves off as First Army personnel and in one incident they secured thousands of gallons of gasoline from a First Army dump.[172] Between January 29 and March 22, the Third Army took Trier, Coblenz, Bingen, Worms, Mainz, Kaiserslautern, and Ludwigshafen, killing or wounding 99,000 and capturing 140,112 German soldiers, which represented virtually all of the remnants of the German First and Seventh Armies. An example of Patton’s sarcastic wit was broadcast when he received orders to by-pass Trier, as it had been decided that four divisions would be needed to capture it. When the message arrived, Trier had already fallen. Patton rather caustically replied: “Have taken Trier with two divisions. Do you want me to give it back?”[173]