Category: All About Guns

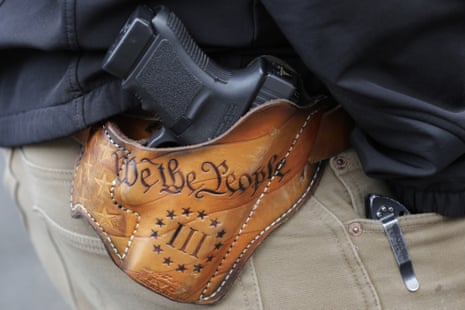

Six million Americans carried guns daily in 2019, twice as many as in 2015

The trend is expected to continue, after the supreme court ruling earlier this year overturning strict limits on public gun-carrying

An estimated 6 million American adults carried a loaded handgun with them daily in 2019, double the number who said they carried a gun every day in 2015, according to a new study published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The new estimates highlight a decades-long shift in American gun ownership, with increasing percentages of gun owners saying they own firearms for self-defense, not hunting or recreation, and choosing to carry a gun with them when they go out in public, said Ali Rowhani-Rahbar, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington, and the study’s lead author.

A landmark supreme court case this summer overturned a New York law that placed strict limits on public gun-carrying, ruling, for the first time, that Americans have a constitutional right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home.

While recent surveys show that nearly a third of American adults say they personally own a gun, the percentage who choose to regularly carry a firearm in public is smaller, with about a third of handgun owners, or an estimated 16 million adults, saying they carried a loaded handgun in public at least once a month, and an estimated 6 million saying they did so daily, the study found.

But public gun-carrying has appeared to increase rapidly in recent years. A 2015 study by the same researchers, using the same methodology, had found that 3 million adults said they carried a loaded handgun daily, and 9 million did so once a month.

Today, the number of adults carrying a gun daily is probably even higher than the 2019 estimate, thanks to a record-breaking increase in gun sales during the pandemic, Rowhani-Rahbar said. “We have every reason to believe this is a trend that is probably going to continue,” he added.

The 2019 study is the most recent available peer-reviewed estimate of how many Americans regularly carry guns in public, he said, and an equivalent post-pandemic survey has yet to be conducted.

While the effect of permissive gun-carrying laws on gun crime has been sharply debated inside and outside research circles, “the totality of evidence is leaning toward an association between those [permissive] policies and an increase in violence,” Rowhani-Rahbar said.

But he said more research is needed, including increased examination of how often “carrying results in self-defense or protection in a way that saves lives”, as many American gun owners believe it does.

Demographically, those who chose to carry a gun in public in 2019 were more likely to live in the south, the study found. Four in five gun carriers were male, and three in four were white, Rowhani-Rahbar said. Other demographic factors, like education and household income, did not make a difference in whether gun owners chose to carry their guns in public or not, he said. About a quarter of the gun carriers had a household income of at least $125,000 a year, and nearly a third had graduated from college, the researchers found.

Only about 8% of handgun owners and carriers were at the lowest income level, making less than $25,000 a year.

The increase in self-reported handgun carrying comes as more US states have passed laws to make it easier to carry a gun in public, with dozens of states removing the requirement that residents had to obtain a “concealed carry permit” in order to carry a concealed firearm on their person.

“The country has been moving as a whole, in the past two or three decades, very clearly and dramatically toward loosening gun-carrying laws,” Rowhani-Rahbar said.

Rowhani-Rahbar’s study found that a lower percentage of gun owners chose to carry in public in states that had very strict carrying laws, but that there wasn’t a substantial difference between states where it was easy to get a permit and states that required no permit at all.

But the handful of large states that had strict carrying laws, including New Jersey and California, are now in the process of changing them, thanks to the supreme court’s decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v Bruen this June, said Adam Skaggs, the policy director at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which advocates for increased regulation of firearms.

“Bruen is only going to accelerate the number of people carrying guns in public,” Skaggs said, noting that, anecdotally, the number of gun-carrying permits being issued in those states is already on the rise.

The 2019 gun-carrying study was based on the self-reported behavior of a nationally representative sample of US adults living in firearm-owning households. Because of opposition from gun rights advocates, there are no official government statistics on the number or demographics of US gun owners, or even the exact number of annual consumer gun sales in the US, meaning that survey-based estimates are sometimes the best statistics available.

The Best Shotguns (Top 5 Fight)

Designed for the XM5 and XM250 (above), the multi-component 6.8×51 mm round may prove to be the “next big thing” in rifle ammunition.

Most progress within the firearm industry is measured in small increments and spread over years or even decades. Since the early 20th century, advances in materials and manufacturing processes have yielded stronger actions, better barrels and more consistent ammunition that performs a whole host of specialized tasks very well. Likewise, operating-system tweaks and modular enhancements have marched steadily onward. On the accessory front, turning night into day has become affordable and the process of accurate ranging, wind reading and compensating is now less about skill than technological prowess.

But, monumental changes—the kind that affect firearm designs for longer than the average human’s lifespan—are relatively rare events. They also happen to be primarily ammo-driven. For example, flintlocks appeared in the 17th century and were the arm du jour for more than a century. The percussion-cap systems that replaced them in the 19th century bridged the gap to metallic-cartridge firearms a few short decades later. As the 20th century dawned, smokeless powder and centerfire, brass-cased cartridges had completed a transformation that endures to this day. If some of my contemporaries are right, the newest developments in cartridge-case technology represent a leap forward that will rival those trendsetters of previous centuries.

The melding of different metals into cartridge cases dates back to the beginning of the metallic-cartridge era. In “The Book of Rifles,” W.H.B. Smith (1948) notes that the same British Army colonel who gave us the standard Boxer priming system developed a successful, hybrid case made of coiled brass with a soft-iron head. Chamber sealing was the problem being addressed by that mid-1800s design. Various ratios of copper, zinc and other elements were tried before the current recipe for cartridge brass was determined to be the “best-case” solution.

Aluminum cases date back at least to the development of the .30-40 Krag. In recent years, combinations of different metals and synthetic materials have been tested in hopes of finding something superior to standard cartridge brass. While reductions in weight and production cost have driven the majority of modern efforts, the quest to enhance rifle-cartridge performance is the impetus for the most notable advances.

As previously detailed in these pages, the Army’s Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) efforts have resulted in multiple, unique 6.8 mm cartridge designs. Each of the companies involved has tried to develop a solution to the Army’s reported desire to penetrate modern, peer-level body armor far beyond close-combat ranges. The selections of SIG Sauer’s 6.8×51 mm hybrid-case ammunition, XM5 carbine and XM250 light machine gun as solutions have been met with both fanfare and skepticism. While the velocities that are reported for the 6.8×51 mm, and its .277 SIG Fury commercial counterpart, seem to generate the most excitement, this cartridge’s projectile energy is likely to be the main driver of the DOD’s interest.

According to SIG’s published numbers, its hybrid steel-and-brass cartridge case allows chamber pressures to reach a whopping 80,000 psi. Subsequently, its 150-grain projectile is reported to leave a 16-inch barrel at 2,830 fps with 2,667 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy. Running those numbers through a ballistic program shows that SIG’s loads should fly flatter and hit much harder than anything used in current battle rifle and light machine gun designs, including 7.62 NATO/.308 Win. loads, out past 1,000 meters.

That’s impressive, but what does it mean for those of us who live, breathe and shoot at the pleasure of the commercial market? Nothing at the moment. However, if the performance of the .277 SIG Fury, and the durability of rifles firing this cartridge, bear out over the long term, we should see other, similar products come to market as well. The resulting ammo options could be serious game changers for anyone who wants to maximize the reach and projectile energy of their rifle(s).

For now though, several barriers stand in the way of any substantive commercial use of this technology. The initial problem is availability. As of this writing, only one .277 SIG Fury load is shown as in-stock with the maker, and it’s a conventional, full-brass-case design, not the hybrid-case scorcher. Likewise, barrels for retrofitting select bolt-action platforms and the main semi-auto that SIG plans to chamber in the cartridge appear to be in a sort of perpetual unicorn status.

Cost is another issue. The hybrid case version of this cartridge runs $4 per round. With DOD being the main customer right now and Lake City Arsenal reportedly still gearing up to fill the Army’s needs, I would not expect the ammunition situation to improve anytime soon.

Pushing a bullet faster so that it will fly flatter and hit harder is one thing. Doing it without rapidly burning out barrels or prematurely wearing out other parts has proven difficult with several past attempts to achieve game-changing muzzle velocities. My personal experiences parallel the historical record in showing that the Army’s small-arms-acquisition efforts often focus too much on reaching specific “milestones” and too little on solving problems that may pop up.

I’m going to be uncharacteristically optimistic on this point and assume the Army will ensure that this will not be a problem prior to fielding these new weapon systems. If that’s the case, our warfighters should be well-positioned to take advantage of all that the 6.8×51 mm cartridge has to offer. Conversely, if the DOD acquisition folks running these programs fumble again, the results could be catastrophic for the men and women who rely on their rifles and light machine guns for success.

One bit of reassurance on barrel wear concerns comes from a reliable source within SIG, who told me the special material technology used in their 6.8 barrels can hold up to this high pressure cartridge. However, that’s the extent of my information.

I hope that my reservations about the DOD’s new cartridge and small-arms solutions are proven unwarranted. I’d want to have the option of advancing my personal-rifle game with the same technology. However, previous letdowns have increased my usual wariness of hot new cartridges that are pitched as the rifleman’s answer to the laws of physics.

SIG’s hybrid-case design has become Uncle Sam’s solution, but until we civilian shooters get our hands on the ammunition and rifles that use it, the verdict will be out on commercial viability. As with any significant leap in firearms evolution, the words of gunwriters, advertisers and military acquisition officers have little bearing on success. Only hard use over time will tell whether or not hybrid-case technology will markedly advance small-arms progression.