If you want a single dramatic example of how much America has changed in the last century or so, stop talking about trips to the moon and super computers and start talking about this: in 1910, two brothers, Temple and Louis Abernathy, saddled up a pair of ponies and rode alone from their home in Frederick, Oklahoma, to New York City, almost 2000 miles away, to see Teddy Roosevelt give a speech. At the time, Louis, called “Bud”, was 10 years old, Temp was 6.

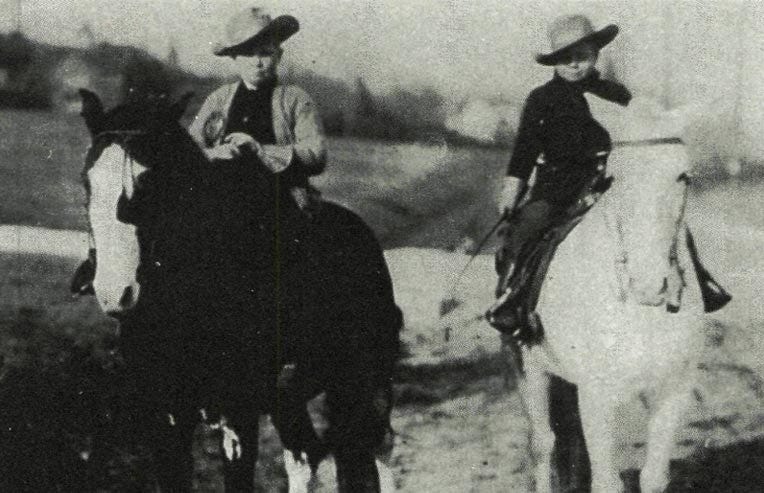

Louis rode his father’s horse, Sam Bass, and Temple rode a pony named Geronimo. Temple was so small that he had to climb on a stump to mount, and often slid down the pony’s leg rather than drop to the ground. They rode without maps, watching the sun and asking directions as they went. Behind their saddles they carried bedrolls and bacon, and oats for their horses, and they paid food and hotel bills by check. They wore broad-brimmed hats, long pants and spurs, and stayed in touch with their father through telegrams and occasional phone calls.

[…]

Difficulties did occur. The boys faced a blizzard. Geronimo foundered and had to be replaced with a horse that was named Wylie Haines after an Oklahoma deputy. Temple came down with a fever, and he was once almost swept away crossing a river.

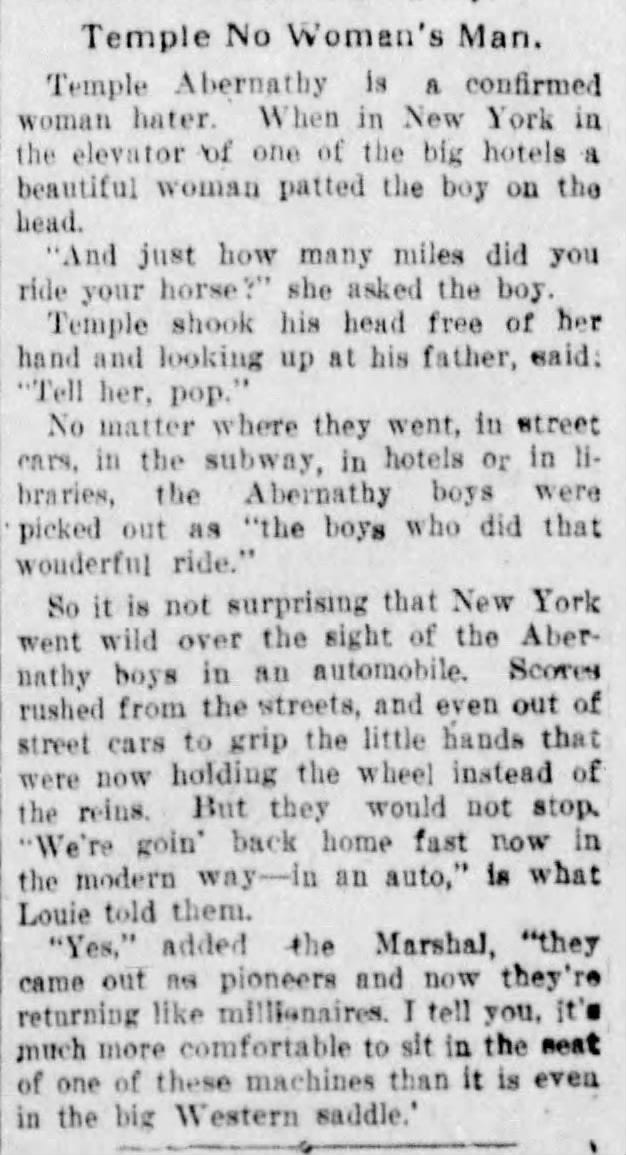

After two months on the road, alone, they arrived safely in Washington, D.C., where they were greeted by the Speaker of the House and met President Taft, whom they felt a fine man, but inferior to their hero Teddy Roosevelt. Two weeks later, they were in New York City riding behind Teddy in a ticker-tape parade in Roosevelt’s honor. He had just returned from a grand hunting trip to Africa.

For an encore, the two pre-teens shipped their horses home by train, bought an automobile and drove it back to Oklahoma. And that’s when things got really crazy.

“All you have to do is just get your feet in the stirrups and hang onto the reins.” ~Temple Abernathy

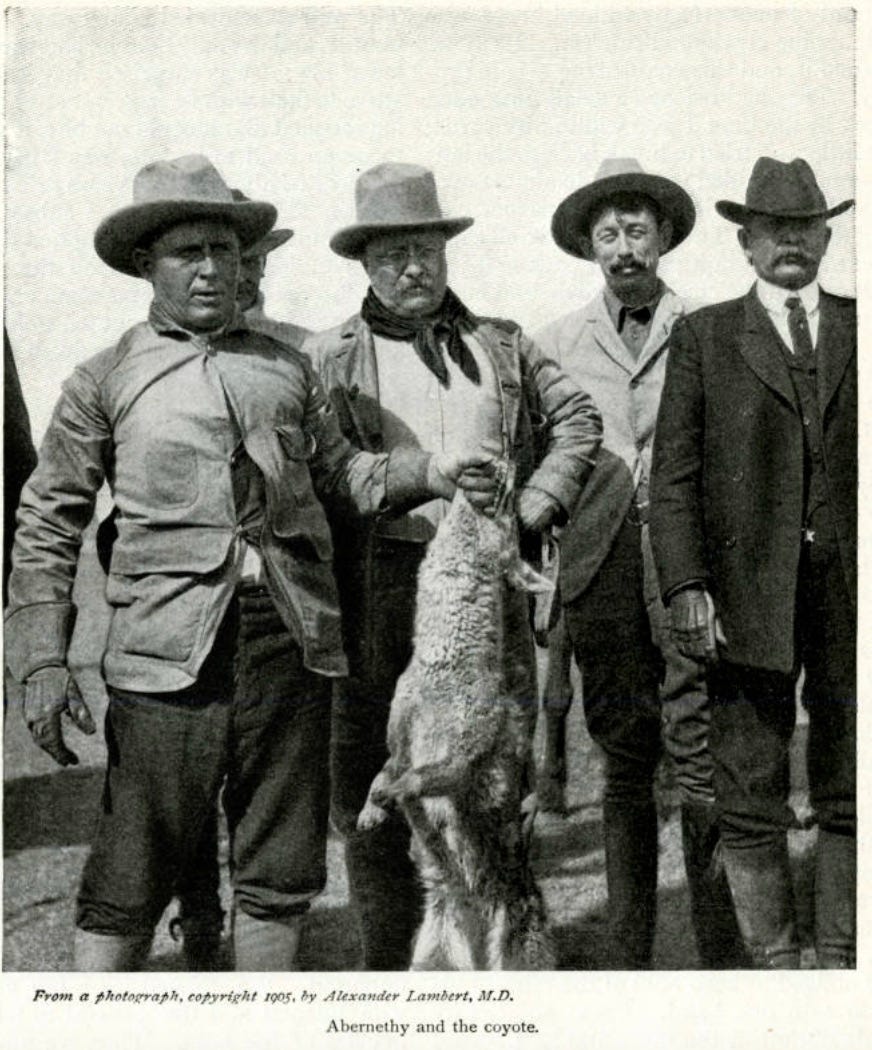

What’s the opposite of a helicopter parent? That would be John Abernathy, United States Marshal for the western district of Oklahoma. Abernathy was, by any standard, a singular man. A working cowboy at 9, by his mid-20’s, Abernathy had become famous for his unique method of hunting wolves: he dragged them out of their dens’ alive with his bare hands, earning the nickname “Catch-’Em-Alive” Abernathy. (Abernathy actually shoved his bare hand into the animal’s mouth and then used wire to bind the jaws shut.) This skill so impressed Teddy Roosevelt, who came to Oklahoma to hunt with Abernathy, that he made Abernathy, all 5’2” tall, a U.S. Marshal, the youngest in American history.

Two years after that, in 1907, Abernathy’s wife, Jessie Pearl, died, leaving Jack to raise six children under the age of 9. He managed with help from his parents and a frontier attitude about what we might call “age-appropriate activities”. Grief, never mentioned in the accounts, undoubtedly played a role in it, too, but what sort of role I’m not qualified to say.

It deserves to be mentioned that the great ride to New York in 1910 was not the Abernathy boys’ first rodeo. A year earlier, in 1909, Temp and Bud had ridden from Oklahoma to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and back, a 1300-mile round trip, done at the ages of 5 and 9, completely alone.

If you’ve ever driven through the Texas panhandle and northern New Mexico, you know that this is wide-open, lonesome country, one that seems barely settled, even today. In 1909, it was still the haunt of outlaws and bad men.

the Santa Fe trip had been riddled with near-disasters. Bud’s horse Sam Bass, borrowed from his father, and the Shetland pony mix named Geronimo were sure-footed. But Temple contracted diarrhea by drinking gypsum water and sprained both ankles trying to dismount. Bud was forced to lie awake one night, firing his shotgun into the darkness toward a pack of wolves that circled while his brother slept. The boys ran out of both food and water between stops, and were saved by the kindness of strangers.

The most chilling episode was a note scribbled by the point of a lead-tipped bullet on a brown paper sack, addressed to “The Marshal of Oklahoma” and delivered to the Abernathy home. “I don’t like one hair on your head, but I do like the stuff that is in these kids. We shadowed them through the worst part of New Mexico to see that they were not harmed by sheepherders, mean men, or animals.” It was signed A.Z.Y., the initials of a rustler whose friend had been killed in a shootout with Abernathy.

I’m fascinated by the Abernathys because, until a year ago, I had never heard of them, and I felt it a shame that this story had fallen into the cracks of American history. Secondly, I feel a special connection to the Abernathys because my grandmother, Nellie Estell Davis, was their exact contemporary, born in 1902, in almost exactly the same place, Mangum, Oklahoma, to a teamster and sometime horse thief, Oliver Jack Moore, and his wife, Laura.

My grandmother, who spent the first years of her life in a tiny west Texas town called Throckmorton, said that one of her earliest memories was of Ollie Jack on the run. Ollie Jack had been missing for several weeks when he appeared one night out of the dark, on a horse, stopped just long enough to kiss my grandmother and great-grandmother, and then rode off again in a great hurry, back into the dark. Or, at least, that was the way she remembered it.

As far as earliest memories go, that’s a good one. Who knows if it’s true. What I can say, is that Ollie Jack Moore and Jack Abernathy were born a few months apart in adjacent counties in west Texas, travelled in the same circles, and were sort of in the same business…sort of.

Bud and Temp proved to be a restless pair. After returning from New York they got the itch to go again, and in 1911 they accepted a challenge put forward by a pair of Coney Island promoters: ride across the continent in 60 days. If it could be accomplished in the allotted time, without sleeping or eating indoors, they’d each be paid $5,000, a regal sum. This is what I meant when I said “things got crazy”.

So, in 1911, the Abernathy boys rode their horses from New York City to San Francisco, 3616 miles in 62 days, a cross-country horseback record that still stands. A crazy accomplisment for an adult, almost unimaginable for a pair of children. Unfortunately, the Abernathys didn’t get paid, having taken two days too long to make the trip. (Their horses ran off in the Great Salt Desert of Utah and it took the boys three days of chasing them on foot to catch them.)

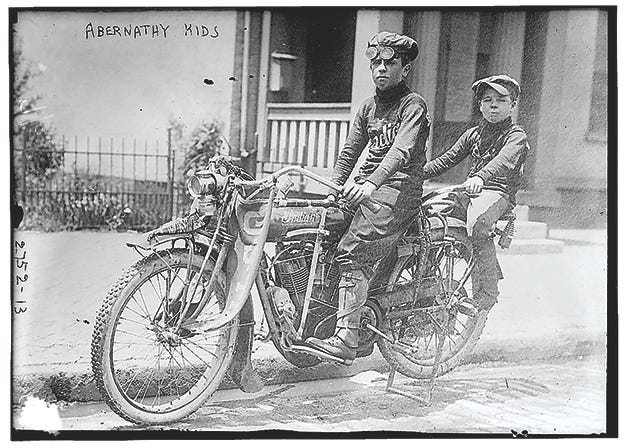

After 1913, when they returned from their great motorcycle ride to New York, the Abernathy boys were never again in the spotlight. They had ridden, by horse, car and motorcyle, more than 10,000 miles in four years, starred as themselves in a silent movie, and gone for a plane ride with Orville Wright. Then they settled down to ordinary lives. Bud, who died in 1979, eventually became a lawyer, practicing in Wichita Falls, Texas, while Temp, who died in 1986, worked in the oil and gas industry in Oklahoma.

But, back to my first point, that the story of the Abernathy boys is as good an indication of how much the world has changed as any discussion of super computers or moon landings. In 1910, children were vastly more common—my grandmother, Nellie Estell, was one of a dozen born to Laura and Ollie Jack, ten of whom reached adulthood—and children were vastly more involved in the activities of the adult world. Before the First World War, children didn’t just ride off on unbelievable adventures, children worked, sometimes in dangerous miserable conditions.

We all know about Shorpy Higginbothan.

And “The Girl”,

These photos were taken by an investigator working for the National Child Labor Committee, established in 1904 to look into the conditions of child labor in America, where 18% of all children between the ages of 10 and 15 worked. What the committee found shocked the conscience and Congress, eventually resulting in the ending of most child labor practices.

The point, however, is that, before World War I, children did things that we don’t think of as childish, which is how it had always been. Children have always been much more capable than we currently give them credit for being, for better (the Abernathys) or worse (like poor Shorpy). Yes, children should be children, free to do childish things, but they also need to be challenged and given progressive responsibility as they grow older. Our failure to understand this is one of sadder things about our current world.

The second sad thing, of course, is the closing of possibility. 1910 America was a wild and wide-open place. It was exciting, loud, grubby, glittering, frequently coarse and surprisingly refined, all at the same time. There were righteous causes to champion, and great injustices to fight. But, above all else, you could do things. It wasn’t exactly a frontier, anymore, but close enough for a pair of boys to mount their ponies and ride across. And that’s the biggest change of all, so many possibilities are gone, so much has been foreclosed to us and our children.