Month: November 2023

My Teachers Pension check has cleared!

The beginning

In early 1951 a plan was put into motion whereby the Air Force might qualify for the 1952 Olympic Games held in Finland. In addition to the smallbore rifle team, the fiercest Air Force pistol competitors were Alan Luke, John Kelly, LTC Charles Densford and Col. Thomas Kelly. At the time, Col. Kelly was not aware of the place in Air Force history that awaited him.The tipping point

Following an attack during the Korean War, General Curtis LeMay went to Kimpo Air Base to take stock of the situation. Learning that fallen U.S. Airmen had perished with M2 Carbines in their hands after their apparent futile attempts to load them with .45 cal. service pistol magazines, the general vowed “never again.” After becoming Chief of Staff of the Air Force, he was able to make good on that promise. The general reached out to Col. Kelly to organize the first Air Force Marksmanship School at Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX. Col. Kelly’s assignment was to 1) Train and organize competent gunsmiths; 2) Establish a marksmanship school; and 3) Organize and field the best competitive shooters in the world. In typical military fashion, the colonel complied.

Many of the early gunsmithing “recruits” were aircraft engine mechanics, fighter pilots or other maintenance personnel who just liked to target shoot or hunt. From that early nucleus came the Air Force’s Gunsmithing “Shop” with pistol, smallbore and high power rifle, shotgun and subsequently running boar (now moving target) sections. An ammunition section was also formed to find the best loads, using their own 100-yard test tunnel. The shop would test a few rounds of ammunition from every manufacturer and, once they found the best, they would buy the entire lot. We knew when we were issued ammunition that we were getting the best available.

With the gunsmithing program underway, efforts turned to establishing a marksmanship school. The first contingent of Air Force shooters arrived at Ft. Benning, GA, to attend the U.S. Army’s advanced coach class in 1958. [Editor’s note: For reference, the Army formed its marksmanship unit in 1956, the Navy in 1957.] The Air Force marksmanship school “went live” later that year and present-day Air Force “Red Hat” rifle range instructors are the direct result of that original program.

With gunsmiths and a marksmanship school in place, Col. Kelly turned his attention to his final set of orders—making the best shooters in the world. Air Force shooters from 1959 until the program was discontinued in 1969 performed extremely well. I will only cover the accomplishments of the pistol team of which I was a part of and knew from firsthand experience.

Team composition

The majority of the early team members came from within the Air Force but there were some who came from the other Services. The first was Bill Mellon who came over from the Navy, then me, Arnold Vitarbo, from the U.S. Marine Corps. I was a member of the Marine Corps Pistol Team from 1961 through most of 1963, and was an established “2650 Bullseye” shooter for the Corps. In those days, whenever we encountered the Air Force Team at matches we were very impressed by their skill and professionalism, so much so that I wanted to become a part of it. During November of 1963, I completed my 10th year in the Marine Corps and decided to join the Air Force. After my discharge from the Marine Corps, I was turned down by an Air Force recruiter on a normal enlistment and actually was headed to Hawaii where we planned to live.

Col. George Van Deusen, Commander of the Air Force Marksmanship School, helped get me assigned directly to the team at Lackland AFB. It should be noted that Col. Van Deusen, a former fighter pilot with the “Flying Tigers,” often traveled with us and usually shot well over 2600 himself. When I arrived at Lackland I found that of the 15 shooters assigned to the Pistol Team, seven of them were current 2650 shooters, including the team captain and coach. (Note that all of these scores were fired with open sights, no scopes.) During my first half-year on the Air Force team in 1964, I fired in over 20 matches and had a 2646 match average, but was not able to make the Blue Team until later that year. My first match as a firing member of the Blue Team made me realize just how tough these guys were. From here on, I would like to list some of the highlights of our team’s accomplishments and put them in perspective.

-SSGT John Mahan broke 2650 12 times and never won a match with it. He was the only shooter I ever met who actually had his sights adjusted for a controlled “jerk.” Anyone else who shot his guns always shot high and to the right.

-In 1966, Capt. T.D. Smith III shot his .45 cal. wad cutter in centerfire matches and his “hardball” gun in the .45 stages for the entire year, with the goal of winning the National Trophy at Camp Perry. After 20 matches and an average close to 2650, he was, instead, sent to Vietnam.

-Capt. Franklin C. Green held the bullseye record for a while with a score of 2665. He injured his left hand so he switched and broke 2660 with his right hand. He became National Champion in 1968.

-TSGT Alvin R. Merx was the first man to shoot 300 over the .22 National Match course. (He subsequently equaled that score several more times.) Merx complained all the time because he hated shooting and said it was boring. He used to assemble distributor caps at a Ford Motor plant in Detroit and said that is what he enjoyed doing.

-Myself, Capt. T.D. Smith III, Capt. Frank Green, SSGT John Mahan and a few others also shot 300 in competition in the National Match course on different occasions. The first time I shot over 2660 (2664) I walked off the line thinking I had the match won, but soon found out that I came in second to T.D., who shot a 2666. In 1968 at Camp Perry, the Air Force made a clean sweep of the Nationals. We won the warm up match, all three guns and Frank Green won the Grand Aggregate. SSGT Edwin L. Teague won the National Trophy Individual Match and we also won all three Team Matches. In the American Rifleman magazine, the reporter said that the Air Force won everything except Lake Erie.

One team only

In those days, there were no separate Conventional and International teams. Those of us who could do both, shot in all of the major matches of each. Our Blue Team in Conventional was usually made up of the International shooters that included:

- Capt. Franklin C. Green, 1964 Olympic Silver Medalist in Free Pistol, 1968 National Pistol Champion, 2650 Club and President’s 100.

- Capt. Thomas D. Smith III, 1964 Olympic Team for Free Pistol, World Champion Center Fire and the retired record holder with a score of 599, 1963-64 Interservice Pistol Champion with a score of 2658-140X, (T. D. shot over 890 with the .22 so many times that it became common place for him), 2650 Club, President’s 100.

- SSGT Arnold Vitarbo (author), 1968 Olympic Team in Free Pistol, 1966 World Championships Free Pistol fourth place finish, 1967 Pan American Games Free Pistol fifth place finish, Team Gold Medal and Individual Gold, 1985 and 1968-1970 World Championship Team Member with a 568-match average in Free Pistol, 1969-1985 Free Pistol Record holder with a 571, 1969-1981 Standard Pistol Record of 586, 1985 Air Pistol Record of 584, 1973 National Free Pistol Champion, 1966 National Center Fire Championship, Distinguished in Rifle, Pistol and International, averaged 288 in individual and Team Matches with the Service Pistol for six seasons, 2650 Club, and President’s 100 seven times.

- SSGT Edwin L. Teague, 1964 Olympic Team in Rapid Fire and 1968 National Trophy Pistol Champion. Ed was a tremendous Police Combat Action shooter and had unbelievably quick reflexes. He later became the head of the SWAT program for the Arizona State Police. He was also part of the 2650 Club and President’s 100.

- LT. Gail Liberty shot as high as 2625 in the Conventional Pistol matches and was a member of the 1966 World Championship Team. After she retired from the Air Force, she made the National Team in Women’s Sport Pistol and Women’s Air Pistol.

Something to pass along

We had a large team score board set up at each match and were required to post our scores. The team would always gather around the score board after the match for open discussion. Although there was much camaraderie among the team members, when the match began, it was “dog-eat-dog.” I feel this attitude was very healthy and that it contributed to our overall success. If you were “thin skinned” you would not have lasted very long on the team.

During team discussions, the subject of how to handle match pressure would always come up. In their own way, each shooter would finally admit they used some form of mental training, including imagery. The mental preparation normally began weeks before a major competition. The closer the “big” match came, the more we would get into our “shell.” These thoughts would include hearing ourselves being called to the firing line, getting our guns ready, etc. The night before a big match, we would try to imagine in more detail actually firing the match, hearing the range commands, the noise and also preparing for any problems that might arise like weather, target breakdowns, etc. When the command was finally given to commence firing, before each shot or string of shots was fired, we would rehearse the entire shot or string in our mind. This mental imagery included breathing, rise of the gun, watching the sights, feeling the trigger pressure and follow through. Immediately after this exercise, we would raise the gun and fire a well-planned shot or be ready for the commands for the sustained fire stages.

I still teach the following techniques to my students in my Coaching and Advanced Marksmanship Clinics. We would try to imagine seeing our sights clearly with our eyes closed. This is normally an acquired skill and takes time to master. It also helps to dry fire in a dark room or closet to get the feel of the trigger and how a smooth break should feel.

Closing remarks

It is my opinion that the reason for the overall skill level that was present during the 1960s was in large part due to the Air Force and its program. We were expected to act like professionals and were treated as such. The performances of the Air Force Team had a snowball effect: As the Air Force improved, the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit at Ft. Benning improved along with the Navy shooters who, in turn, began to be a force to be reckoned with. The Air Force had to improve to beat the Army and Navy, and they in turn did likewise. The overall result was extremely high scores with a very high expectation level. There are record scores that were fired in the 1960s and early 1970s that are still standing.

There are other members too numerous to include in this article and I apologize for not mentioning anyone before 1962, but I was not on the team at that time.

The first N-Frame was the Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector, 1st Model, often called the “Triple Lock” (left)

and this one is a rare target model. It was replaced at the behest of the British during WWI with the Hand

Ejector, 2nd Model, which never got a nickname. Both of these are .44 Specials. Photos By Yvonne Venturino

It seems like we older gun’riters are forever fawning over the legendary Smith & Wesson “Triple Lock” which incidentally is called Hand Ejector, 1st Model by collectors. Perhaps it is because besides being the very first of S&W’s N-Frames sixguns, the Triple Lock was also the introductory vehicle for the .44 Smith & Wesson Special.

Then there is the Hand Ejector, 3rd Model also nicknamed Model 1926. Later the Hand Ejector 4th Model was introduced. It was divided into two variations with the names of 1950 Military for the fixed sight version and 1950 Target for ones with adjustable sights.

But what about the Hand Ejector, 2nd Model? It is seldom mentioned, never got a name and was just as good a revolver as the above mentioned ones and actually far more historical.

This particular handgun was introduced 100 years ago during World War I. The Brits got themselves enmeshed in Europe’s continental war, and as usual, were short of weapons. They contracted with S&W to alter the Hand Ejector, 1st Model to accommodate their rather puny .455 Webley ammunition, but wanted changes. They said that battlefield mud and debris would foul its special 3rd lock and the ejector rod’s protective shroud.

Perhaps more importantly S&W felt the Hand Ejector, 1st models were too expensive at $21. By removing the ejector rod’s shroud and the intricately machined 3rd lock on the crane they could reduce retail price to $19.

And so was born the Hand Ejector, 2nd Model. For the American market the primary caliber offered was .44 Special. Also some were made as .38-40, .44-40 and .45 Colt but they numbered only in the hundreds each. According to Roy Jinks’ History of Smith & Wesson, by September 1916 the company had produced 74,755 N-Frame revolvers in .455 caliber for the British. Of those, 69,755 were Hand Ejector, 2nd Models. The other 5,000 were Hand Ejector, 1st Models because the British didn’t want to wait for the changes being made to the 2nd model.

All of those had 6-1/2-inch barrels, full blue finish except for the color case hardened trigger and hammer and a lanyard ring on the butt. Grips were checkered walnut and sights were S&W’s trademark “half-moon” front with groove in the frame’s topstrap for a rear. I have a sample in my collection that factory letters to the Canadian Government in 1916.

Even so, the military duty of Hand Ejector, 2nd Models was just beginning. Being almost as bad as the British for declaring war while lacking weapons, the United States entered WWI in April 1917. The US Army was desperate for handguns, so S&W was contracted to provide N-Frame revolvers altered to function with rimless .45 ACP cartridges—this was done by snapping the cases into little 3-round spring-steel clips. The Hand Ejector, 2nd Models were given the military designation of Model 1917. All were fitted with 5-1/2-inch barrels, lanyard rings and smooth walnut grips. Finish and sights were the same as for the Brit’s contract revolvers.

Production of Model 1917’s was enormous. Jinks’ book says 163,476 were made for the US Government in their own serial number range. Those are marked “United States Property” under their barrels as mine is. After WWI ended the company kept this model in their catalog until 1949 and produced about another 50,000. This order included 25,000 sold to the Brazilian Government in the late 1930’s, with many of those returning to the United States for the surplus market in the 1980’s. The commercially made Model 1917’s had checkered walnut grips instead of the military’s plain ones.

And that brings us back to the Hand Ejector, 2nd Model .44 Special. In nobody’s world could it be called a big selling item. It was dropped from the S&W catalog in 1940, and again referring to Jinks’ authoritative book, only 17,510 were sold in 25 years.

Barrel lengths offered were 4, 5 and 6-1/2 inches with full blue or full nickel for finish. Some were fitted with target sights but the vast majority had sights as described for the .455 variation. Grips were checkered walnut and lanyard rings were not standard. As interested as I have always been in N-Frame S&W handguns, I have never seen a Hand Ejector, 2nd Model in any barrel length but 6-1/2 inches, any finish but blue, any type of sights but fixed or any .38-40, .44-40, or .45 Colt chambering. (Original chambering that is. Many .455’s were rechambered to .45 Colt in bygone years.)

Nigh on 20 years ago I wandered into a nifty little gun store on a trip to Los Angeles. To my utter amazement, in the handgun case was a Hand Ejector, 2nd Model .44 Special, blue finish with 6-1/2-inch barrel. I paid for it and made arrangements for it to be (legally) shipped back to Montana. It took me years to get around to factory lettering it but upon doing so I learned it had been sent to Charleston, W. Va., in 1929. Having been born and raised in that state, the provenance of this revolver dictates I keep it forever.

Besides, it shoots pretty good!

S&W Combat Masterpiece Revolvers

Well I liked it! NSFW

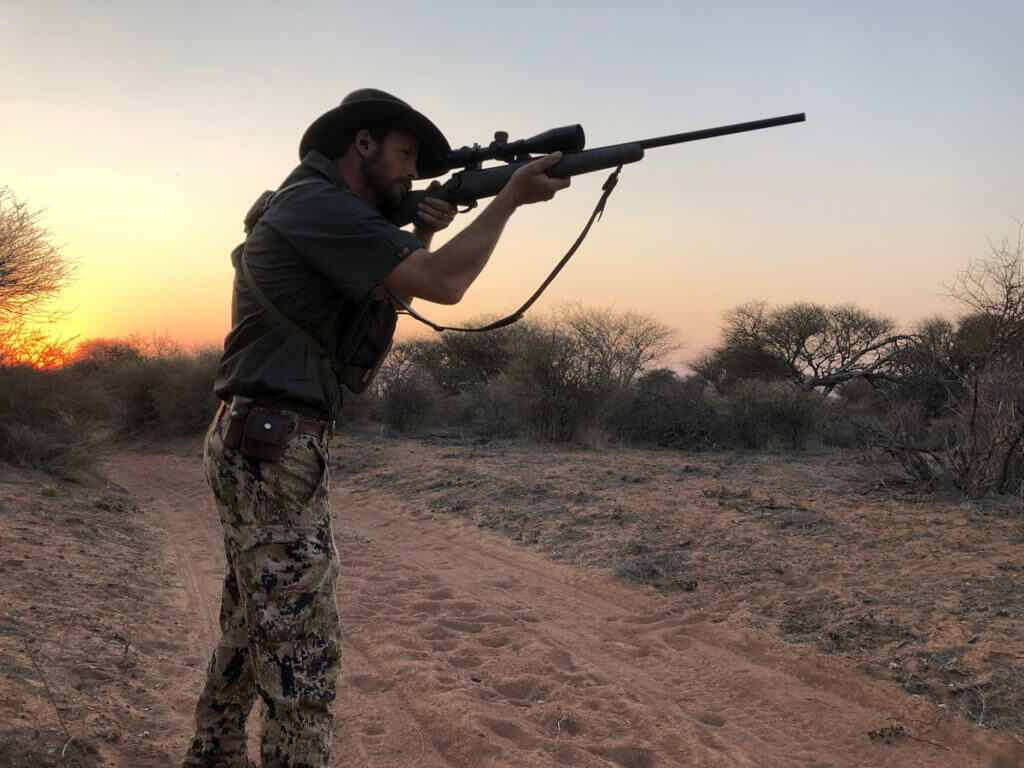

Dawn broke cold over the high country, with a threat of snow hanging in the air. Twelve cow elk grazed in a meadow at 11,500 feet, one small five-by-six bull still sleeping off his night of debauchery. I crept into place, rested my .300 Winchester Magnum atop a lightweight tripod, and squeezed the trigger. The bull never regained his feet.

Two years later I approached the same meadow, this time with a friend who carried a 6.5 Creedmoor on her shoulder and an elk tag in her pocket. Fresh elk tracks showed the way and we flushed another, bigger 5X6 bull. I cow called, my friend pressed the trigger, and another bull lay still in the snow. Both elk succumbed to a single shot. Only the duration of the kill was different. Mine died almost instantly; the other bull stayed on his feet for almost a minute, even though he was hit perfectly.

IS BIGGER BETTER?

For decades big, hard-hitting calibers held court across America’s hunting grounds. Recoil wasn’t considered the detriment it is today, indeed some shooters and hunters acclaimed hard-kicking rifles as superior, and accused those chambered in more mannerly cartridges as being sissified. This opinion was created by the projectile performance of the day. Simply put, the then-new high-velocity cartridges of the 20th century generated so much speed that traditional bullets struggled to maintain their composure when impacting heavy hide and bone. Bigger, heavier bullets had a better chance of holding together and penetrating deeply.

Today the pendulum has swung, and many hunters and shooters opine that bigger, harder-hitting calibers belong with folks of limited intelligence. According to these same hunters and shooters, anyone with enough electronic devices and high enough projectile BC (ballistic coefficient) can kill a mastodon at 1,000 yards with a 6mm Creedmoor. The one thing they do have right is that things have changed. Coming full circle, it’s all about bullet performance. Today’s premium projectiles are incredibly accurate and consistent. More to the point, they penetrate deeply and perform reliably at a wide variety of impact velocities. What this means is that today’s small, recoil-friendly calibers can kill as cleanly as yesterday’s bigger, harder-hitting calibers.

IS SMALL AND SWEET SHOOTING BETTER?

Smaller calibers and cartridges kick less. They tend to be accurate and are certainly easier to shoot well. Loaded with a premium bullet they penetrate deeply and create a devastating wound channel. They do everything a big, hard-kicking caliber can do, right?

Wrong. There are two things they can never do as well:

Hit Hard: Two elements affect how hard a bullet impacts. The first is frontal diameter. The greater the frontal diameter, the more surface area and tissue the bullet impacts directly. Remember; surface area in a circle increases exponentially as diameter increases. The second element is weight. The heavier a projectile is the harder it hits. Consider the difference between getting hit by a pencil eraser traveling at 100 feet per second (fps), and a softball traveling the same speed. Neither will penetrate your skin, but the softball will hit much harder due to greater weight and diameter.

Penetrate Deep: In a nutshell, bigger, heavier bullets penetrate deeper than smaller, lighter projectiles of the same design. That said, modern-day bullet design has leveled the scale, to a degree. Projectiles such as Barnes’ TTSX, (a monolithic, solid copper/alloy bullet), and Federal Premium’s Terminal Ascent (built with a rapid-expanding jacketed lead front and a solid copper rear portion) maintain weight and drive deep, even in lighter, more friendly calibers.

The final word, though, is that a 200-grain bullet from a .300 Win Mag will out-penetrate a same-design 130-grain bullet sent from a 6.5 PRC.

THE UPSHOT

Light/sweet-shooting calibers are easier and friendlier to shoot, and now (with premium bullets) perform and penetrate admirably. Bigger calibers kick harder, but also hit harder and penetrate better. So what is best? The answer is, of course, situation and species specific. The light/sweet crowd will say, “It’s all about shot placement. Just wait for a good broadside shot and place your bullet right in the boiler room”.

To an extent that’s true. But what if your quarry never offers you a broadside shot? Let’s consider a common elk-woods scenario: You’re on a dream hunt in the Rocky Mountains. You’ve hunted hard, and you want to kill an elk in the worst way. On the last day of your hunt, you finally find a bull, a good one with heavy six-point antlers. You’re set up on a little rocky outcropping, using your pack as a dead rest. The bull is going over a thick timbered ridge and isn’t giving you a shot at all.

You keep your crosshairs on him, hoping against hope that he steps into a clearing and gives you a shot. Finally, it happens; 350 yards away he stops, turns, and bugles back down the canyon. You can see his shoulder clearly between tree trunks, but he’s steeply quartered toward you. Your crosshairs are steady, your finger on the trigger. But you subscribe to the “wait till they’re broadside” strategy, and inside your rifle’s 6.5 PRC chamber rests a rapid-expansion 140-grain bullet. What do you do?

If you’re honest and ethical, you let the bull walk.

The chance that your soft, rapid-expansion bullet will make it through the many inches of hide, flesh, bone, and sinew protecting the vitals at this angle is remote. You pull that trigger, and you’re likely in for a long, heart-wrenching recovery effort. But if you continue to wait for that broadside shot the bull will likely walk over that ridge and out of your life forever.

Now, hit rewind and change your chosen bullet to a 130-grain Federal Premium Terminal Ascent. Suddenly, you’ve completely altered this scenario. You’re not going to hit a massive old bull elk very hard with a 130-grain bullet at 350 yards, but an accurate shot with this deep-penetrating bullet will kill him, even through the point of the shoulder. And that’s what has changed. That’s the new difference.

Rewind the scenario again, and change your rifle to a .300 Win Mag. Shooting a 200-grain Federal Premium Terminal Ascent bullet, you will hit that bull very hard and kill him very quickly. No doubt about it, this is the better elk round. If you can handle the kick and shoot it well, by all means use it. But if the recoil loosens your fillings and crosses your eyes every time you squeeze the trigger, you better lighten up.

This scenario changes dramatically, of course, if the primary species you hunt is deer, pronghorn, or sheep. For smaller, lighter boned members of the big game family the 6.5 PRC and similar cartridges are optimal. Loaded with one of the premium bullets mentioned above they will penetrate into a deer’s vitals from any angle. Recoil is civilized, and terminal performance all you will ever need. But what if you use one rifle to hunt a broad spectrum of big game – elk one week, deer the next, and moose the third?

The author with a big mule deer harvested with a rifle chambered in .280 Ackley Improved; one of his favorite all-around big game hunting calibers.

The author with a big mule deer harvested with a rifle chambered in .280 Ackley Improved; one of his favorite all-around big game hunting calibers.In my opinion, the ideal solution for an all-around rifle is a mid-level cartridge like the .280 Ackley Improved, .30-06 Springfield, or 7mm Remington Magnum. Recoil generated by these cartridges will not rattle your teeth or cross your eyes, yet they hit hard enough and penetrate admirably. Loaded with premium bullets, they’re cheerfully adequate for everything from coyotes to Alaskan moose.