Month: October 2023

S&W M&P Shield 9 NOT Reliable

Shiloh: The War is Civil No More

Sixteen nations sent forces to fight in the Korean War on the allied side. One of the lesser-known contingents was Ethiopia’s Kagnew battalion. It was equipped almost entirely with surplus American WWII gear.

(WWII-era Willys jeep of the Kagnew battalion in Korea.)

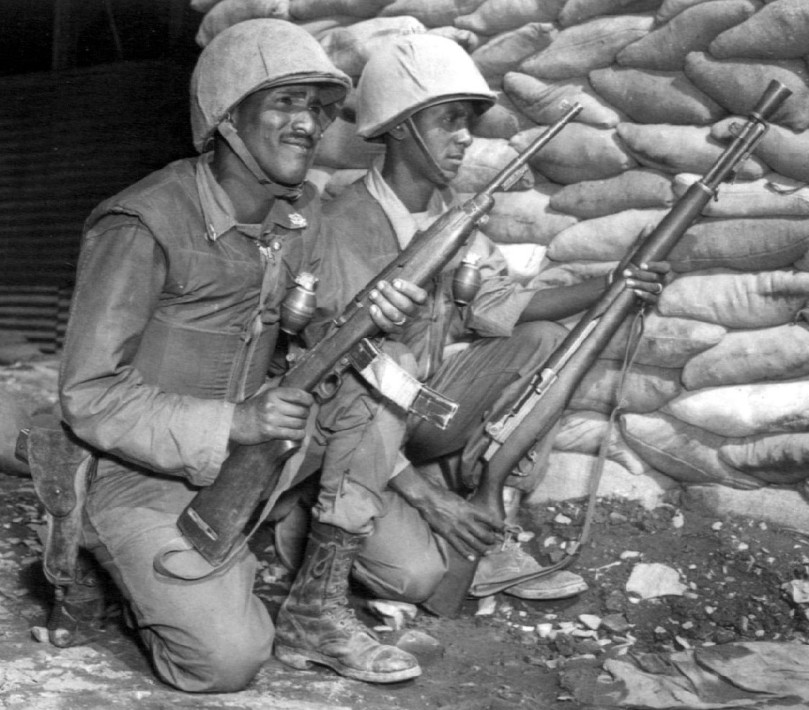

(Ethiopian soldiers in the Korean War. All of their kit – M1 steel pot helmet, OD green fatigues, web belt, M1911 sidearm – is WWII American gear.)

Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie was an early proponent of what is today called collective defense. Prior to WWII, when Ethiopia was invaded by Italy, he made an unsuccessful plea to the League Of Nations for military assistance.

(Emperor Haile Selassie decorates wounded Kagnew battalion members after their return to Ethiopia.)

When North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950 and the United Nations (of which Ethiopia was a charter member) made a plea for an international force, Haile Selassie sought for his country to set the example and participate. Ethiopia was one of only two African nations to fight in the Korean War, the other being apartheid-era South Africa, and was by far the least-wealthy nation to contribute troops.

In August 1950, a decision to deploy Ethiopian forces to South Korea was finalized. After consultations with the US Army it was decided that the force should be one infantry battalion. An appeal for volunteers in the Ethiopian army received tremendous response and the Kagnew battalion was hand selected by Brig.Gen. Mulugetta Bulli. A good percentage of the officers and senior NCOs were WWII veterans.

(The battalion colors.)

The Kagnew battalion’s name was chosen by the Emperor and referenced the horse of Gen. Ras Makonnen, a cousin of the previous Emperor and Haile Selassie’s father. In Ethiopian chivalry, the names of a knight and his horse were interchangeable. This custom lingered on in Ethiopia’s royal family into the 20th century.

While there was only one Kagnew battalion as an organization, there were three actual units, one relieving another throughout the Korean War.

Once selected, the Kagnew soldiers began a grueling eight-month training course. A mountain range in Ethiopia was found to be similar to the Korean peninsula’s topography, and the training was done there. At the conclusion of the training, the battalion’s first deployment numbered 1,122 men (85 officers and 1,037 enlisted) and was split into four companies plus a small GHQ unit. The overall commander was always a Lt.Colonel or higher; and there were four company commanders usually of Captain rank.

(Lt.Col. Teshome Irgetu, first commander of the Kagnew battalion)

The first Kagnew battalion departed Africa on 12 April 1951 from the city of Djibouti, at that time part of France’s Afars & Issas Territory colony. The battalion was transported to the war aboard the WWII-veteran troopship USNS General J.H. McRae. During WWII, this ship had been a Squier class US Navy vessel, USS General J.H. McRae (AP-149) but by the time of the Korean War it had been stripped of guns and transferred to the Military Sea Transportation Service. This ship also transported the Belgian, Greek, and Dutch contingents to Korea.

(USS General J.H. McRae (AP-149) during WWII.) (photo via navsource website)

(The disarmed ship in MSTS service, here with the arrival of the Kagnew battalion in South Korea in 1951. This WWII-veteran ship was deactivated in 1954 and scrapped in Taiwan in 1987.)

The General J.H. McRae reached Busan on 6 May 1951. Initially, the US Army had planned to lump the Ethiopians in with Colombia’s contingent for retraining. However almost as soon as they disembarked, it was clear that the Kagnew battalion had been supremely trained in Ethiopia and no further basic military instruction would be needed.

(Col. Kebede Guebre with Syng-man Rhee, president of South Korea.)

Instead, the Ethiopians were sent to a six-week US Army weapons course at Tongnae, South Korea to familiarize them with American weapons.

(A US Army M4 Sherman tank, a WWII design, is demonstrated to the Ethiopian soldiers at Tongnae. The Ethiopians never operated the Sherman; the training was to familiarize them with it’s profile.)

For clarity the US Army designated all non-American units in Korea by an English name. The battalion was designated EEFK (Ethiopian Expeditionary Force – Korea) in US Army documents. Later as the battalion’s tremendous reputation in battle grew, this was abandoned and it was referred to by it’s Amharic-language name in US Army communications.

(An American soldier talks with Kagnew battalion members.)

The battalion was assigned to the US Army’s 7th Infantry Division. It was not a novelty or add-on for diplomatic purposes, rather it de jure replaced one of the 7th’s American battalions.

(Insignia of the US Army’s 7th Infantry Division, the temporary parent command of the Kagnew battalion during the Korean War.)

(An American general of the 7th Infantry Division with the Ethiopian battalion. The switch (twig) is used in traditional Ethiopian military cheers.)

The Kagnew battalion’s first combat was at the “Kansas Line” defensive perimeter during the late summer of 1951. On 12 August 1951, the battalion had it’s first major battle, the Jeoggeun Mountain engagement.

(South Korean monument to the Ethiopian victory at Jeoggeun Mountain.)

In September 1951, the Kagnew battalion took part in the US Army’s successful operation “Cleaver”, an offensive to liberate hills near Samhyon. This was followed in October by the famous Heartbreak Ridge battle.

(Kagnew battalion soldier in Korea, with M1 Garand rifle and M1 pot helmet, both WWII American items.)

In January 1952, the Kagnew battalion took part in the Punchbowl engagement. By this time, the battalion was so well regarded in the US Army that it was being assigned it’s own operations, in this case operation “Clamor”, which ran until the end of February. In March, the first turnover occurred and the second Kagnew battalion relieved the first.

(Ethiopian troops during the January 1952 Punchbowl engagement. As they hailed from an African desert country, there was initially some concern about how the Kagnew battalion would perform in winter conditions. They had no problems fighting in the snow.)

The second Kagnew battalion repeated the weapons acclimation training course of the first. It saw combat for the first time in June 1952 as part of the Iron Triangle battle. In September 1952, the Ethiopians participated in the “Showdown” operation, followed by the assault on Yoggog-ri in October, then the operation “Smack” offensive in January 1953.

(The commander of the second Kagnew battalion turns over the national flag to the commander of the third. The actual physical Ethiopian flag taken to Korea was from the imperial palace.)

In April 1953, the second turnover occurred and the third Kagnew battalion relieved the second. Because of experiences shared from the first two deployments, the familiarization training time was halved and completed in May 1953. Almost immediately, they entered combat as part of the Alligator Jaws battles.

The third Kagnew battalion won the battle of Yoke-Uncle, a hilltop engagement where the Ethiopians destroyed an entire Chinese battalion. The Kagnews were awarded the Hwarang Order of Merit by the South Korean government for this battle. The battalion ended the war fighting the Pork Chop Hill engagements.

(Kagnew battalion soldiers in 1953, near the end of the Korean War.)

Following the July 1953 armistice, the Kagnew battalion withdrew to the US Army’s Camp Casey facility in South Korea. In April 1954, the third Kagnew battalion rotated out and was replaced by a much smaller token Ethiopian force to monitor the armistice. Ethiopia continued sending tiny infantry contingents to South Korea until 1956. The last lone Ethiopian representative to the armistice monitoring team left on 3 January 1965.

A total of 3,518 Ethiopians served in Korea before the armistice. They suffered 121 KIA and 536 wounded. There were 0 POWs, as the Kagnew soldiers had a near-fanatical determination to never be captured alive. Their zeal to either win in combat or fight to the death quickly became legendary in the 7th Infantry Division.

(The Ethiopian Kagnew Combat Pin, which roughly equated to the US Army’s CIB and was worn on the same position on the uniform.)

Their reputation in combat was tremendous. While all of the allied contingents were publicly praised for diplomacy’s sake, inside the US Army the Kagnew battalion was legitimately regarded as an excellent infantry asset; well-trained, competent, and easy for other American components of the 7th Infantry Division to interoperate with.

(Kagnew battalion members at rest. The sign regarding POWs may seem confusing today; at the time it was a point of pride that they would conduct themselves better in Korea than the Italians had in their country during WWII.)

All troops of the three Kagnew battalions were decorated by their own military. From the South Korean government, the third deployment was awarded the Hwarang Order of Merit, and seven individual soldiers received lesser decorations for the Yoke-Uncle battle.

(A South Korean streamer is added to the Ethiopian flag in 1953. This photo shows the Lion of Judah shield patch worn by officers on dress occasions, above the United Nations sleeve emblem.)

From the USA’s government, the whole Kagnew battalion in it’s entirety was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, and each soldier received the Korean Service Medal. The second deployment also received a US Army Distinguished Unit Citation, and there was one Silver Star and eighteen Bronze Stars awarded to individual Ethiopian troops by the US Army.

(A US Army general attaches the Presidential Unit Citation to a guidon of the Kagnew battalion.)

WWII weaponry used by the Kagnew battalion

The Kagnew battalion’s entire kit was American, and nearly all of it WWII-surplus equipment.

(Typical gear of the Kagnew battalion. Except for the then-new M26 hand grenades, their entire kit is WWII-era American equipment. Both officer and enlisted have M1 steel pot helmets. The officer has a M1911 (.45ACP) sidearm and a M12 ballistic vest. He is armed with a M1 carbine, with two 30-round “crook” magazines “jungle-styled” (duct taped together). The enlisted man has a M1 Garand rifle with the optional M2 flash hider cone fitted. They are wearing US Army OD green fatigues but with Ethiopian rank insignia.)

When North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, the Ethiopian army’s standard rifle was the M30. A bolt-action Mauser design, this rifle was an offshoot of FN’s Mle.1924 customizable platform, and similar to the 98k of WWII Wehrmacht fame. Ethiopia also used two similar guns, both confusingly designated M33; one being a lightened M30 for alpine use and the other a short cavalry carbine. All of these weapons fired the 7.92x57mm Mauser cartridge.

(M30 rifle)

Some of these rifles survived the Italian occupation and were reissued after WWII. They were joined by M33s, which were Belgian-made near-clones of the WWII German 98k. Gaps in the force were filled in by abandoned Italian weapons or Enfields left behind by the UK after the liberation.

During the planning stage in 1950, it was debated if the Kagnew battalion would bring firearms they were familiar with, or be rearmed with American guns after their arrival. It was decided against bringing these Mauser-type rifles with the battalion. The 7.92x57mm cartridge was not standard to the American or Commonwealth logistics streams, and considering the varieties of British and American rifle calibers already in the theatre, the last thing wanted was a new cartridge. A lesser concern was that while the 7.92 Mauser round was not standard to any allied contingent, it was produced in communist China, so any Ethiopian guns lost in battle would be immediately useful to the enemy.

One of the most legendary rifles ever made, the M1 Garand was the standard American battle rifle during both WWII and the Korean War. It was also the main weapon of the Kagnew battalion. The semi-automatic M1 was 3’8″ long and weighed 9 ½ lbs. It fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge (2,800fps muzzle velocity) from an 8-round enbloc. With a good shooter (which most of the Ethiopians were) it was accurate to 500 yards.

(M1 Garand rifle with close-up of the 8-round enbloc and .30-06 FMJ ammunition.)

There is little that can be said about this legendary rifle that already hasn’t been said elsewhere. It was tremendously popular with the Kagnew soldiers and the battalion’s record speaks for itself as to it’s effectiveness.

Another WWII-veteran firearm used by the Kagnew battalion was the M1 carbine. This lightweight weapon was normally issued to Ethiopian officers and senior NCOs, and also to recoilless rifle gunners, mortarmen, and rear-echelon troops. Basically it was given to a soldier who’s role did not warrant a rifle, but where some weapon larger than a handgun was needed. The semi-automatic M1 carbine weighed just 5 lbs empty and was 2’11” long. It fired the American .30 Carbine cartridge from a 15- or 30-round detachable magazine.

(M1 carbine.) (National Rifle Association photo)

The M1 carbine was liked by the Ethiopians but somewhat less so than the M1 Garand rifle.

A small number of M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR) were used by the Kagnew battalion. This had not been one of the guns initially envisioned for loan by the USA, and the small number given to the battalion were apparently drawn from the 7th Infantry Division’s own pool as the Kagnew’s reputation grew. Typically, a BAR was carried by one member of a platoon on forward reconnaissance missions. BARs were tremendously popular with the Ethiopians, perhaps as much or more so then the Garands.

(M1918 BAR.)

The M1917A1 was the first heavy machine gun issued to the Kagnew battalion. Weighing 103 lbs (including tripod and water can), this water-cooled full-auto gun fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge (same as the Garand) from a fabric feed belt. It fired at 600rpm and the liquid cooling allowed for long periods of sustained fire. Back in Ethiopia, the Kagnew soldiers had trained on leftover air-cooled WWII Italian machine guns of low quality, so the M1917A1 was a huge step up. The Ethiopians often mounted the gun on a WWII Willys jeep.

(M1917A1 machine gun on a Kagnew battalion jeep.)

Later in the Korean War, the M2HB .50cal joined or replaced the M1917A1 as the Kagnew battalion’s heavy machine gun. Like the M1 Garand, this WWII weapon is legendary and the Ethiopians appreciated ‘Ma Deuce’ as much as everybody else. The full-auto M2HB fired the 50BMG cartridge (2,910fps muzzle velocity) from the closed bolt position, with a 600rpm rate of fire. Compared to the M1917A1, the M2HB had a much more punishing round and the Kagnew soldiers adapted it into something of a fire support weapon like the recoilless rifles.

(Ethiopian soldiers with Ma Deuce in the Korean snow.)

The M18 recoilless rifle was a WWII weapon, having seen use at the end of the European part of the war and battles throughout 1945 in the Pacific. This was the initial anti-armor weapon issued to the Kagnew battalion. The M18 fired a 57x303mm(R) round out to about 450 yards. For the Ethiopians, M18s were issued at the company level, two or three to a company or roughly a dozen or so for the entire Ethiopian contingent. By the time the Ethiopians got M18s, it was regarded as insufficient against the T-34 tank. These were mostly used as a fire support weapon against machine gun nests, pillboxes, and the such.

(Typical fighting position for an Ethiopian recoilless rifle team during the Korean War. The other firearm shown is a M1 carbine.)

The next step up was the M20 recoilless rifle, which gradually replaced the M18 in the Ethiopian contingent. This was (barely) a WWII weapon; having been developed by the USA late in the war and only seeing combat in the last Pacific battles, namely Okinawa. The M20 fired a 75x408mm(R) round out to about 3 miles maximum, which was about the upper limit the gunner could aim with the optics. Both HEAT (anti-tank) and fragmentation (general use against infantry) recoilless rounds were used. As it turned out, the Kagnew battalion rarely encountered enemy tanks and like the M18, the M20 was generally used as a fire support weapon.

(Ethiopian M20 team in Korea. This photo shows the nationality shoulder rocker on the American uniform.)

The Kagnew battalion’s GPMG (general purpose machine gun) was the M1919A4, another American WWII design. This full-auto, air-cooled weapon fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge from 250-round belts, with a cyclical 600rpm rate of fire. Generally the Ethiopians used this gun for engagements under a ½ mile.

(Ethiopian M1919A4 team in Korea.)

The Kagnew battalion’s mortar was the M2. A 60mm weapon, this mortar had entered American service in 1940 and served all of WWII in all theaters. It was still the standard American mortar of it’s caliber range during the Korean War. While classified as a “light infantry mortar” by the US Army, this weapon had excellent range (over 1 mile) for it’s caliber and was extremely reliable. The 3 lbs mortar shells were available in a variety of types. In the Kagnew battalion, M2s were usually paired up, two to a fire team, with one or two fire teams per each of the battalion’s four companies.

(Kagnew battalion mortar team in action. The Ethiopians made fearsome use of this weapon. In June 1952, a two-section 60mm mortar team of the Kagnew battalion inflicted massive casualties on a Chinese infantry company it caught in the open.)

The Kagnew battalion did not have any organic artillery. Instead, assets of the 7th Infantry Division supported it as needed. The standard weapon was the M2A1 howitzer. A WWII-veteran design, this 105mm weapon had a range of about 7 miles. While the artillery was part of the 7th Infantry Division overall, as time went on some Ethiopians qualified on this artillery piece.

(Kagnew battalion soldiers training on a M2A1 howitzer of the US Army 7th Infantry Division.)

No Ethiopian aircraft took part in the war. All of the Kagnew battalions air resupply and combat support missions were provided by the US Air Force.

In 1950, the Ethiopian army had three helmets in service. The M30 was the design which they had taken into battle against the Italians in the late 1930s. Many of these were lost in combat, others seized and melted as scrap by the Italians during the occupation. Some survived and were reissued after the liberation.

The M30 was already on it’s way out of service by 1950, and anyways there was no way the Emperor was going to send his men to Korea in a stahlhelm-style helmet so close to the end of the Third Reich.

A small number of Mk.II Tommy helmets had been left behind by the British after the liberation. There would not have been enough to equip one battalion without stripping other units of their headgear, and there may have not been enough army-wide.

This left the M45 pith helmet. A post-WWII copy of a similar Belgian-manufactured pith helmet (itself modeled on the British colonial design), the M45 was made in Ethiopia. Compared to the pre-WWII version the M45 was somewhat less fancy with a more basic puggaree (fabric wrap) and simpler shape. Obviously a pith helmet offers much less ballistic protection than a steel helmet, but this is what the Kagnew battalion took to Korea.

Once in the theatre, it was decided to re-equip the Kagnew battalion with the American M1 steel pot helmet. This was the standard American helmet from WWII into the early 1980s. Besides obviously offering better protection to the Ethiopians, the 7th Infantry Division felt that their M45s might attract attention as no other nationality on either side of the conflict was using such a style.

The Kagnew soldiers wore M45s on their journeys to and from Korea and the first deployment wore them in non-combat settings as well. Later deployments wore them for ceremonial settings. As far as is known, they were never worn into battle. Surprisingly the M45 remained the standard Ethiopian helmet into the early 1960s and some were still in use as late as 1972.

(Kagnew battalion soldiers arriving in South Korea with M45s.)

The M1 pot helmet was popular with the Kagnew battalion. Typically they applied the 7th Infantry Division hourglass to one side and the Ethiopian national roundel on the other. Some M1 pots went back to Ethiopia after the armistice and the M1 was the standard helmet from the 1960s up until the massive Soviet resupply during the Ogaden War at the end of the 1970s.

(Kagnew battalion soldier wearing a M1 steel pot helmet with 7th Infantry Division emblem.)

(A 2-star American general awards the Bronze Star to a soldier of the Kagnew battalion. Here, the Ethiopian national roundel is visible on the M1 pot helmet.)

The Ethiopian uniform was based on the WWII British Ptn.37 design. This was worn in general use for some time by the first deployment and by all the Kagnew deployments for ceremonial settings. For combat, standard US Army OD green fatigues were issued, but with Ethiopian rank insignia. An “ETHIOPIA” rocker was worn on the shoulder. Winter clothing was also US Army standard, sometimes with a Lion Of Judah sleeve patch.

(Ethiopian troops en route to Korea, wearing M45 pith helmets and their own army’s Ptn.37-style uniform.)

(Kagnew battalion solder wearing the M1 pot helmet with US Army-standard coat and web belt. The small suitcase is part of a WWII-vintage field communications circuit.)

Use of WWII American weapons in Ethiopia after the Korean War

Troops of the third battalion were allowed to bring some equipment (mainly M1 Garands, M1 carbines, bayonets, canteens, M1 pot helmets) back with them after the armistice. As the initial 1950 plan called for the weapons to be loaned by US Army, a sum of $45,000 ($400,766 in 2016 dollars) was paid by Ethiopia.

Regrettably, Ethiopia saw perhaps the least tangible benefit of participation in the Korean War. After the armistice, American disbursement of WWII-surplus weaponry was targeted primarily towards NATO in Europe and Rio Treaty countries in Latin America.

The M1 Garand was immensely popular with Ethiopian soldiers in Korea, and several hundred came back to Ethiopia with returning Kagnew units. Beginning in the mid-1950s the country repeatedly requested American assistance in transitioning from the FN Mausers to the Garand. The first M1 Garand tranche came in 1963, when 19,923 Garands were delivered. Of these, 500 came from the Department of the Navy (which includes the US Marine Corps) and the balance from the US Army. In 1968, a further 758 Garands were transferred from US Army warehouses, and the final batch was in 1970 – 1971 when 1,122 Garands were drawn from US Army warehouses.

(Ethiopian army radioman in 1961, armed with a M1 Garand. This was two years before the first large import, so this particular M1 was almost certainly ex-Kagnew battalion.)

Additionally, in 1966, three M1C sniper variant rifles were transferred, and the following year six of the M1D version. These were the first specialist sniper rifles in the Ethiopian army.

(Sniper variants of the Garand.) (photo from Olive-Drab website)

In all, 21,812 M1 Garands were transferred from the United States between 1963-1971. Despite the M1’s growing obsolescence in the face of Cold War-era weapons proliferation in Africa, these were extremely popular rifles in the Ethiopian army. By the beginning of 1972, the Garand was the main battle rifle of the Ethiopian army.

(Ethiopian troops armed with Garands in April 1963.)

Even as the last M1 Garands were delivered in 1971, it was already beginning to be replaced. The first M14 assault rifles were delivered from the USA at the end of 1971. Altogether 23,450 M14s were delivered between 1971 and the communist takeover in 1974. Throughout the mid- and late 1970s, the M1 Garand and M14 served together as Ethiopia’s standard rifles.

In the midst of the Ogaden War against Somalia, now-communist Ethiopia’s allies in the USSR undertook a massive airlift of weapons in August-September 1977 including tens of thousands of AK-47s. After that war ended in 1978, remaining M1 Garands were withdrawn due to their age and non-availability of American ammunition.

Just like the M1 Garand rifle, small numbers of M1 carbines came to Ethiopia in 1953 with returning members of the Kagnew battalion. As this gun was also liked by Ethiopian soldiers, more were requested. In 1963, a large transfer of 13,040 M1 carbines was delivered, followed by sporadic small batches throughout the next eight years. Altogether, 16,417 M1 carbines were delivered from the United States between 1963 – 1971. Of these, 1,095 were drawn from US Air Force stockpiles, the rest from the US Army. During the 1970s the carbines began to be replaced by Uzis purchased from Israel. Little was said about them thereafter, and they were no doubt withdrawn from use after Ethiopia switched to East Bloc weaponry at the end of the 1970s.

A small number of M1918 BARs were imported at the same time as the first batch of Garands. During the Korean War, the Kagnew soldiers liked this gun, as it gave full-auto capability to a single soldier. Even as the M14 deliveries in the 1970s made this redundant, the few BARs delivered remained in use and some saw combat during the Ogaden War alongside Soviet-made full-auto weapons. Reportedly, one BAR was seen in use by Ethiopian troops during a 1999 border skirmish with Eritrea.

The WWII-vintage C-47 Skytrain had been the main aerial resupply plane serving the Kagnew battalion during the Korean War. In 1958, ten of these planes were delivered from the USA. They served until the end of the 1970s.

During the later part of the Korean War, the USA drew up plans to equip the Kagnew battalion with it’s own organic tank unit. Twenty WWII-surplus M24 Chaffee light tanks were authorized for transfer to Ethiopia in late 1952. This 20-ton light tank had a 75mm M6 gun which the US Army considered insufficient against the T-34, and by that stage of the Korean War they were regarded as secondary tanks.

The Korean War ended in 1953 before the Ethiopian M24 Chaffees could be deployed there, however they remained in Ethiopian use until the late 1970s.

Fate of the Kagnew veterans and legacy

On 12 September 1974 a communist junta known as the Derg overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie. Led by Mengistu Haile Mariam (who eventually got rid of the junta and ruled as absolute dictator), the Derg was, even by communist standards, an especially brutal and horrifying regime.

(The sad end of one of the world’s oldest monarchies, as communist Derg troops (in American M1 pot helmets) shuttle the deposed emperor away from the former palace in a common Volkswagen.)

Following the victory against Somalia in 1977 – 1978, Ethiopia backslid in every imaginable way. During the 1980s Mengistu’s military simultaneously was fighting a nationwide political insurgency and an Eritrean secessionist war; at the same time the country overall was suffering through the infamous 1983-1986 Ethiopian famine.

Mengistu alienated much of the world and Ethiopia’s allies dwindled to outcasts such as Cuba, East Germany, and North Korea. For Ethiopia’s veterans of the Korean War, the latter was to became a problem. As part of it’s aid package, North Korea demanded Mengistu officially disavow the Kagnew battalion, which he did. The Kagnew veterans were stripped of all military decorations and had their pensions revoked. Many were harassed by Mengistu’s secret police, and some fled abroad. The Kagnew veteran’s association was banned, and monuments to the battalion were destroyed. In Ethiopian school textbooks, the nation’s participation in the Korean War was erased from history.

In May 1991, Mengistu was driven into exile. The post-communist government of Ethiopia reversed all of his decisions against the Kagnew battalion veterans (most now in their sixties), however Ethiopia was essentially bankrupt and their pensions went unpaid and little else was done for them.

In 1996, the South Korean government passed legislation that South Korea would pay the pensions of surviving Kagnew battalion members for the remainder of their lives.

(Kagnew battalion veterans at a ceremony in 1999. Some of the unit’s troops were also WWII veterans.)

At the turn of the millennium, the Kagnew battalion experienced a somewhat unlikely surge of popular interest among younger generations of South Korean citizens. Ethiopia’s contribution to South Korea’s fight was reported on numerous times on South Korean television. In 2007, a memorial hall to the Kagnew battalion was opened in Chuncheon, South Korea.

Legislation was passed to give preferential admission to South Korean universities for the grandchildren of the Kagnew veterans. South Korean financial aid helped build a Korean War memorial in Ethiopia to replace the ones Mengistu destroyed. In 2010, South Korean donations paid for forty aged Kagnew battalion veterans to visit the country for the first time since the Korean War.

(South Korean president Park Geun-hye speaks at the Korean War Monument in Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia, in May 2016.)

As of late summer 2016, there are fewer than 300 Ethiopian veterans of the Korean War still alive.

(The Imperial Ethiopian Korean War Medal)

Opinion and Not Legal Advice

-

New York’s Gun Law Amendments: The Hochul Government’s changes are viewed as worsening the issues and not aligning with recent Supreme Court rulings.

-

Opposition to the Second Amendment: New York’s leadership, especially under Hochul and Cuomo, is criticized for curbing Second Amendment rights.

-

Ammunition Background Check Issues: Hochul’s attempt at implementing background checks for ammunition mirrors Cuomo’s failed 2013 attempt, causing processing delays.

-

Unclear Leadership: The recent resignation of the New York Superintendent of State Police, Steven Nigrelli, adds to the uncertainty and complexity of gun law enforcement.

-

Controversial Gun Policies: Policies around firearm storage, proof, and fees for background checks are being challenged as infringements on citizen rights.

New York’s licensed firearms dealers and gun ranges are getting swamped with questions over confusing new laws concerning concealed handgun carry licenses, ammunition, and firearms “transfers” (that is to say, purchases, trade-ins, and giveaways).

In this article, we address these important and timely issues and provide our take, attempting clarification on what the law is.

On enactment and enforcement of York’s Concealed “Carried Improvement Act” (“CCIA”), including recent amendments to the CCIA, licensed firearms dealers and those also operating gun ranges have unfairly suffered the brunt of attacks by frustrated New Yorkers who have seen constant and infuriating delays in their taking possession of firearms and ammunition.

These delays did not occur prior to the amendments to New York’s Gun Law which points to a disturbing fact: the Hochul Government’s changes to the Gun Law, purporting to comply with the June 2022 U.S. Supreme Court rulings in Bruen, did no such thing. In many ways, the Government’s amendments to the Gun Law made matters worse.

Hochul and the Democrat-Party-controlled Legislature in Albany simply gave lip service to the Bruen rulings. As a matter of fact, the Hochul Government merely continues the policy established by her predecessor Andrew Cuomo. The aim of this State Government in the Twenty-First Century is to continue the process of further constraining and constricting the exercise of the right of the people to keep and bear arms in New York, and to do so with increasing rapidity.

It is therefore business as usual for a New York Government that is virulently opposed to the Second Amendment of the Nation’s Bill of Rights.

And it isn’t only New York civilians who are facing frustrations and confusion. The new amendment is also impacting active-duty New York Police Officers. And both citizen civilians and police officers are all taking out their frustration on the wrong people: the Gun Dealer and Gun Range Owner.

This impossible situation is all by design and then enhanced and perpetuated by the Hochul Government.

Is there any way out of this morass?

Yes. But it is important to understand that Hochul’s recent “ammunition” amendment to the Handgun Law isn’t alone the cause of the problem. It is simply a reflection of the New York Government’s long-standing and deep-seated abhorrence of the fundamental right of the people to keep and bear arms and the Government’s contempt for those citizens residing in New York who are intent on exercising their right, regardless of the many obstacles placed in their path by the Government.

It is also important to understand that this new amendment isn’t a standalone provision. It is simply the most recent addition to the Hochul Government’s “Concealed Carry Improvement Act” (“CCIA”).

Moreover, the ammunition background check requirement is not something new that Governor Kathy Hochul and the Democrat Party-controlled Legislature in Albany dreamed up. It has been done before.

Hochul’s predecessor, Andrew Cuomo, tried to impose an ammunition background check system on New York firearms owners in 2013—ten years before the passage of Hochul’s CCIA. Cuomo’s ammunition background check provision was written into the New York Safe Act of 2013. It didn’t pan out, then, just as it isn’t panning out now. The Superintendent of the New York State Police could not get the damn thing to work even in 2014, one year after the Safe Act was implemented. And it was costing the taxpayer millions of dollars.

So, Cuomo scrapped it, and the Superintendent of State Police and those working to get the thing operational breathed a sigh of relief.

Hochul never pointed this little matter out to the public when she resurrected Cuomo’s little scheme.

She, too, is having problems implementing this ammunition background check system—hence the delays in processing transfers of ammunition and firearms. Nothing has changed, ten years after Cuomo originally promulgated an ammunition background check provision and placed it in the Safe Act.

The difference between Hochul and Cuomo is that Hochul doesn’t mind the constant problems and obviously doesn’t care about the many people—citizen civilians, licensed gun dealers and owners of gun ranges, and even active-duty New York Police officers—voicing vociferous and incessant complaints and doing so with justification.

If Hochul is going to create a mechanism of enforcement, then at least make the damn thing work. Otherwise, do away with it. But she won’t do that.

She won’t do that because it is obvious that Hochul relishes the delays. Otherwise, she, like Cuomo, would have either scrapped the thing or would have urged the State Legislature in Albany to formally repeal the amendment or she would have placed continual pressure on the Superintendent of State Police who is tasked with getting this thing to work efficiently and effectively.

But, as far as we can tell, Hochul has done none of these things and has no plans to do so. She simply doesn’t care. She doesn’t care because she is doing exactly what her wealthy benefactors, and what the Biden Administration, and what those citizens residing in New York, who voted her into Office, want her to do. Hochul knows she is on safe ground politically on this, and that is all that matters to her—at least at this moment. Hopefully, this will change as increasing violent crime and the frustration of the public ramps up.

But, what about the New York Superintendent of State Police?

Does he care about the problems he is faced with in getting a notoriously difficult database up and running? This thing does, after all, sit on his lap.

Well, he doesn’t care either because, at this moment, there is no New York Superintendent of State Police.

Steven Nigrelli, the Acting Superintendent and the most recent Superintendent resigned his post on September 23, 2023, after Governor Hochul refused to make his position permanent, ostensibly because he faced employment harassment charges.

- See, e.g., the article published in the New York Post.

- Nigrelli’s resignation took effect on October 6. See Spectrum 1 News.

So, who is the new acting Superintendent of State Police? Who can say? We don’t know. No news account to date we are aware of has reported an appointment of a new acting Superintendent of State Police. So, if Hochul did appoint someone, anyone, she failed to mention that person’s name. And, if she is considering an appointment, she hasn’t made that fact known either.

This only complicates matters, not only for the State Police that cannot get the NICS database working but for every New Yorker who suffers a delay in obtaining either a firearm or ammunition.

New York law now requires a Licensed Gun Dealer and Gun Range Owner to run NICS background checks only through the Superintendent of State Police and not directly through the Federal Government for firearms and ammunition transfers. And keep in mind that, even if Hochul authorized Licensed New York Gun Dealers and owners of Gun Ranges to utilize the Federal NICS system for undertaking background checks, the FBI only does background checks involving transfers of firearms. They are not legally authorized, even if they were willing to do checks on those individuals who simply wish to purchase ammunition.

And this delay is affecting active-duty police officers as well because they are not exempted from the NICS background check requirement either for the purchase of ammunition or for the purchase of firearms beyond Departmental-issued firearms.

If there is a delay in running a check, everyone is, then, in the same boat.

But none of this negatively impacts your run-of-the-mill criminal element or murderous international cartel member that, thanks to Biden’s Open Border misadventure, has enabled millions of illegal aliens to take up residence in our Nation, and like a horrific viral infection, these illegals have coursed through the entire body politic.

The criminal element doesn’t bother with Hochul Gun Regime compliance matters, anyway.

If criminals get hit with a gun charge among other things, these noxious elements can expect a lenient judicial system to give them a slap on the wrist and send them on their merry way to create more mayhem for both police and the average citizen. And this is exactly what is happening in New York.

*For those readers interested in the specific operative State Statutes and Municipal Codes, Rules, and Regulations, feel free to contact the Arbalest Quarrel directly or through Ammoland Shooting Sports News, and we will be happy to provide you with the citations.

To Lawfully Carry A Handgun In New York, the City Government Still Requires A Person To Acquire A Valid Concealed Handgun Carry License That IS Issued By The NYPD License Division

One burning question concerns whether, under the CCIA, a valid concealed handgun carry license issued in a New York county or municipality other than the City of New York enables a license holder to carry his or her handgun for self-defense IN the City of New York.

The answer is an emphatic “no.” Handgun Preemption Laws that most States follow have no application in an Anti-Second Amendment State like New York.

This means that, as long as New York City, or any other county or city in New York, establishes rules and codes that appear legally consistent with the State’s Handgun Law—found in Penal Code Section 400.00 et. seq.—then those jurisdictions are free to create and implement new rules, codes, and regulations that are more detailed and potentially tougher than the State’s own Handgun Law requirements. This has always been true of New York City.

Even with the passage of the CCIA in July 2022, State law does not preempt the Rules of the City of New York on the matter of the City’s continuing refusal to honor the validity of concealed carry licenses issued by another New York jurisdiction.

Anyone who applies for a New York City Handgun Concealed Carry License must comply with the City’s stringent Handgun Rules, the NYPD License Division enforces those Rules rigidly. This means that if a person wishes to carry his or her concealed handgun in New York City, that person MUST first acquire a valid New York City-issued handgun carry license.

But, wouldn’t that mean, from a logical standpoint, that a rule, code, or regulation that’s more stringent than the State law, is, by logical implication, illegal by the very reason that such rule, code, or regulation is more restrictive than the State Law?

Of course. But when was a New York Gun Law ever internally consistent, let alone consistent with the Second Amendment of the Bill of the Rights of the U.S. Constitution?

The U.S. Supreme Court struck down New York’s “Proper Cause” requirement in Bruen, sure. But this doesn’t legally prevent any jurisdiction in New York, be it municipal or county, from establishing its own Gun rules, codes, or regulations, applicable to that jurisdiction that a prospective handgun carry applicant must follow.

New York City requires anyone who wishes to carry a handgun lawfully in the City to obtain a handgun carry license issued by the NYPD License Division, regardless of the fact that a person may already possess a valid handgun carry license issued by another New York City or County.

Doesn’t The Curtailment Of The Proper Cause Requirement Negate The Need To Acquire Multiple New York Concealed Carry Licenses

The fact that no jurisdiction in New York is allowed any longer to require a person to show extraordinary (“Proper Cause”) need as a condition for obtaining a handgun carry license doesn’t legally prevent any city or county from requiring compliance with its own peculiar rules, codes, and regulations involving concealed handgun carry licenses.

In that case, a city or county can mandate that a person obtain a concealed handgun carry license for that jurisdiction, regardless of any other valid New York concealed handgun carry license he or she might happen to hold, applicable for the specific county or city.

At the moment, New York City is the only jurisdiction, now as before, that requires a person to acquire a license to lawfully carry in the City. Nothing in the CCIA changes that old mandate.

Remaining New York Gun-Related Questions Not Presently Before The Courts

One Thorny Question Concerns Whether A Person Domiciled in a Jurisdiction Outside of New York Can Obtain a New York Concealed Handgun Carry License

A New York Gun Dealer asked the Arbalest Quarrel the other day whether a person residing in another State can obtain a New York State handgun license.

The New York State Gun Law doesn’t assert categorically that a person must be domiciled in New York to obtain a handgun carry license. New York case law bears that out. So, the consensus of opinion in the Courts to date is that a person need not be domiciled in New York to obtain a New York Concealed Handgun Carry License.

However, an out-of-state applicant must still comply with both the training and “Good Moral Character” requirements of the CCIA and other applicable State and Federal Statutes.

A Second Thorny Question Concerns The Legality Of Charging A Person Fees For The Purchase Of A Firearm And Ammunition.

The fees are assessed by the State Police, ostensibly to cover the cost of undertaking a background check on a person to verify the person is not under Statutory disability that would preclude the transfer of a firearm and ammunition to that person.

The fee for the transfer of a firearm has increased. But New York never before charged a fee for the purchase of ammunition. It does so now. A fee of $2.50 is now assessed for the background check that the State Police now undertakes on the purchase of ammunition.

Note: The fee of $2.50 applies only to the background check itself, not to the number of boxes of ammunition a person purchases.

But each time a person purchases a new box or boxes of ammunition, there is a new $2.50 fee imposed because the State Police is required to undertake a new background check on that person. It therefore, behooves a person to purchase as much ammunition as he can afford at any one time to keep the fee at a straight $2.50.

A Couple More Points Concerning Fee Assessment On Firearm And Ammunition Transfers

First, the background check is charged to the seller of firearms and ammunition, not the buyer. A seller must provide the State Police with a valid Credit Card. The State Police applies a charge to the seller’s credit card immediately. The seller doesn’t eat the charge but passes the fee onto the purchaser. This is perfectly legal. This creates consternation, and that is understandable. A gun dealer and gun range owner have substantial expenses. They have to make a living, too.

If there is a delay—the usual occurrence—in completing the NICS background check, the transferee must still reimburse the seller of the firearm or ammunition immediately even though the transferee doesn’t take immediate possession of the firearm or ammunition. That is one reason why a person—a civilian citizen or active-duty police officer—gets upset with the Gun Dealer or the owner of the Gun Range. The transferee pays out of pocket immediately and gets nothing for his troubles as he must await the State Police processing of the transfer. That can take hours or even days.

Second, are both the fees and the dollar amounts of those fees lawful? They are. New York law specifies the State Police can assess fees for conducting NICS background checks and also provides a mechanism for determining what dollar amount is lawful.

A Third Thorny Question Pertains To The Legality Of Agency Policy

A third question is whether the Superintendent of the New York State Police can require a person who owns and possesses several firearms to show proof of having acquired a firearm safe to store those firearms.

A licensed New York Gun Dealer and the owner of a Gun Range has posed this question to us.

The New York State Police has required a person who holds several firearms on a restricted handgun premise license to present the State Police with a photograph of that safe.

This suggests that the person does not presently have a firearm safe, which is an expensive purchase, and would probably wish to defer the purchase of a safe if that were possible. It isn’t.

We believe that the State Police can require proof of purchase of a firearm safe once a New York premise license details possession of a certain (arbitrary) number of firearms on a premise license.

Is this true? If so, why?

According to New York Courts, the question is considered more a matter of policy than of law.

But Gun Policy, apart from State Statutes or County or Municipal code, rule, or regulation, still operates with the force of law.

New York Courts have dealt with this issue and have so stated.

When a complainant contests a “Gun Policy, New York Courts have said that the complainant must prove that a given New York Gun Policy is “arbitrary and capricious” before a Court will strike that Policy down.

This follows from the “Primary Jurisdiction of Agency Rule” that Courts have followed since U.S. Supreme Court rulings in the Chevron case that was decided decades ago, and a long line of cases following Chevron, since.

This Term, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken a renewed look at Chevron and is considering either constraining the Court’s rulings in that case or overturning the rulings of Chevron outright.

The Biden Administration is apoplectic with rage over this.

But, at the moment, Courts generally acquiesce to agency decisions because of Chevron. Agencies have tremendous discretion. And, so, failure to prove to the satisfaction of a Court that a gun “policy” is “arbitrary and capricious”—a difficult standard to meet and the burden of which falls on the complainant—the policy will stand.

New York Police Departments are, therefore, given substantial freedom of action to create and implement policy directed at firearms licensing requirements.

This also follows from the fact—as New York Courts routinely make as asserted in their rulings, and that remains “Black Letter Law”—that, while the keeping and bearing of arms remains a basic and indisputable Right, the licensing of one to keep and bear arms remains a privilege.

The Arbalest Quarrel has pointed out that possessing a license (a Government bestowed privilege) as a condition precedent to the enjoyment of a fundamental, unalienable Right is not only logically fallacious and legally unsupportable but also nonsensical.

So, unless, or until, the U.S. Supreme Court has the courage to abolish the nonsense of allowing a State or Federal Government to license exercise of a God-Given Right, the citizen will continue to suffer the consequences of the rudeness of State actors who refuse to countenance the sanctity of natural law, eternal rights.

And the worst consequence by far is the insinuation of Tyranny upon us and our inability to effectively contend with that Tyranny if the citizenry is unable to bear arms to defeat it.

That, of course, is what a Treacherous Government’s concern is really all about—the power of the armed citizenry to thwart the will of the Tyrant who would dare subjugate the common man.

This has nothing whatsoever to do with ensuring “Public Safety” and preventing “Gun Violence.” Those things are nothing more than makeweights, mere cliché, that only a fool would believe. And there are, unfortunately, plenty of them that reside amongst us.

About The Arbalest Quarrel:

Arbalest Group created `The Arbalest Quarrel’ website for a special purpose. That purpose is to educate the American public about recent Federal and State firearms control legislation. No other website, to our knowledge, provides as deep an analysis or as thorough an analysis. Arbalest Group offers this information free.

For more information, visit: www.arbalestquarrel.com.