Uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars

1805 – 1815

“Uniform dress became the norm

with the adoption of regimental systems,

initially by the French army in the mid 17th century.”

– wikipedia.org

1. Introduction.

1. Introduction.2. Coats, Greatcoats, Undercoats.

3. Shakos, Bearskins.

4. Breeches, Trousers, Overalls.

5. Other Items: Pelisse, Dolman, Sabretache, Knapsacks.

6. Bardin Regulations 1812 – 1815

7. Battle and Parade Uniform.

8. Napoleon’s Uniform.

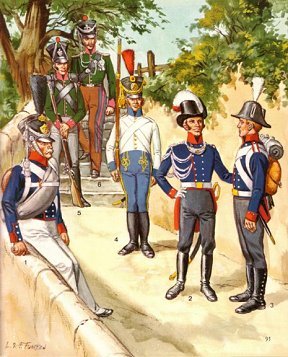

Right: soldiers of small German states. In blue uniforms infantrymen of Oldenburg, in white uniform infantryman of Reuss, and in green uniforms soldiers of Anhalt. Picture by Knoetel.

(In 1810 Napoleon annexed the Duchy of Oldenburg. Tzar Alexander’s sister, Ekaterina, was married to the son and heir of the Duke of Oldenburg. Thus Alexander retaliated by increasing the duties on articles imported from Napoleonic France.

In 1806 Napoleon elevated the states of Anhalt-Bernburg, Anhalt-Dessau and Anhalt-Köthen to duchies — Anhalt-Plötzkau and Anhalt-Zerbst had ceased to exist in the meantime.)

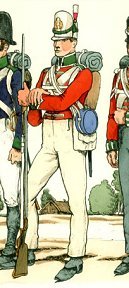

Left: uniforms of soldiers of the US Army in 1812-15.

Left: uniforms of soldiers of the US Army in 1812-15.

(In 1812 the US Army consisted of 7,000 regulars (35,000 in 1815 !),

3,000 rangers, and numerous irregulars.

The Americans were frustrated with the British. In August 1807 USA president Jefferson wrote to T. Leiper: “I never expected to be under the necessity of wishing success to Bonaparte. But the English being equally tyrannical at sea as he is on land, … I say, “down with England.”

The War of 1812-15 was fought between USA and Great Britain. Britain had been at war with France and in order to impede neutral trade with France in response to the Continental Blockade, Britain imposed a series of trade restrictions that the U.S. contested as illegal under international law.

USA declared war on Britain in June 1812 (ext.link). On July 5, 1814, the Americans met the British at Chippewa and drove the redcoats from the field. After two year of failures, it renewed the American soldier’s faith in himself. For the first time American infantry had met and defeated a comparable number of British regulars in open battle. Other U.S. successess came at Plattsburg, Lundy’s Lane and especially in New Orleans. (pictures, ext.links)

Introduction. Introduction.Contemporary observers regarded the French uniforms with unreserved astonishment. Often the monarchs were more preoccupied with the looks of the troops than their generals. Generals Kutuzov and Wellington paid very little attention to uniforms. In contrast Tsar Alexander said he was personally responsible for creating the Russian shako kiver. And he loved parades and reviews. To King George IV (image, ext.link) is attributed the comment that in military dress a wrinkle was unpardonable, although a seam was admissible. (Elting – “Military Uniforms in America” Vol. II, 1977) The uniforms worn during Napoleonic Wars represent the most elaborate display of pomp in the whole history of military dress. Contemporary observers regarded the French uniforms with unreserved astonishment. The luxury of the French uniforms was overwhelming. The veterans of Napoleonic Wars, writing their memoirs in their old age, mourned the passage of such magnificent uniforms. They consoled themselves with the conviction that no greater military splendour, bound up as it was with the charisma of their Emperor, had ever been seen in Europe, or would ever be seen again. It was the ornamental peak of the military uniform in Western Europe. This is identified as being the acme of colorful and ornate uniform.

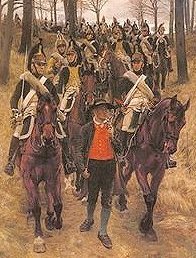

From left to right: Westphalian trumpeter of Garde du Corps in 1812. Westphalian private of Garde-Grenadiere in 1803-1813. Westphalian colonel of Garde du Corps in 1812 (King Jerome Bonaparte’s Guard).

From left to right: Bavarian 7th Light Infantry Battelion in 1808-1811 Naples Dragoon Regiment in 1812 Naples Line Infantry in 1812

From left to right: Bavarian 7th Light Infantry Battalion in 1808-1811 Baden Garde-Grenadier in 1812 Weimar Sharpshooter in 1807 Swedish officer of Leib-Kirassiere in 1807 Hanoverian Bennigsen Battalion in 1813 The cost didn’t discourage colonels and commanders from exhausting their troops’ budgets on expensive parade dresses. As commander of the Guard, Lannes’ enthusiasm for showy uniforms for his guardsmen landed him in serious trouble with Napoleon. Lannes wildly overspend the Guard’s budget and Napoleon replaced him with Bessieres. With such high costs you may think the soldier would be satisfied with three set of uniforms. For example, one for parade, one for service and one off duty. But not the French, oh no 🙂 Most of the uniforms were made of wool, silk, hemp and linen. In the hierarchy of textiles, linen and hemp cloth were followed by fabrics made from tow (hemp) and canvas (hemp). Canvas is a heavy kind of linen cloth. Both wool and canvas are strong and last a long time although wool needs cleaning less frequently and easier then other fibers. The linens were made either of flax or hemp. Hemp linens were coarser than flax linens, but ounce for ounce they were stronger. Hemp was far more common than linen until the late 14th century. Throughout history hemp was used more widely in the countryside than in towns, since almost every farm had its field of hemp. Hemp was brownish-gray, thicker and coarser than linen when new, hemp cloth was often preferred, due to its lower cost.

Linen is cool in summer and warmer in winter than cotton. Linen exceeds cotton in coolness and strength, but unfortunately break easier under tension. Prior to the 20th century, there were public bleaching fields in Europe where dampened linens were spread on the grass to be bleached by the sun to a pale bone color. Ireland, Netherlands and Russia were the largest producers of linen.

|

Coats, Greatcoats, Undercoats. ………. Waistcoat (Undercoat)

The waistcoat of French foot gunner was white (according to Knotel and Elting). But the Zimmerman Manuscript shows them in 1807 in blue waistcoats. The same for the Brunswick Manuscript and year of 1805. Berka Manuscript shows them also in blue for 1809 and Martinet gives them blue for 1807-1814. The foot gunners of Old Guard wore white waistcoats for summer (according to Bucquoy). Other sources gives for them blue waistcoats (Berka Manuscript, Malibran, Rousselot and Rigondaud). If battle was fought on a very hot day some soldiers wore only coats, or only waistcoats. In 1809 at Wagram the gunners of Old Guard went into action on that muggy day stripped to shirts.

Coat (Jacket)

The distinction between various armies normally lay in colours of their coats: Within each army diffent regiments were usually distinguished by “facings” – linings,turnbacks and braiding on coats in colours that were distinctive to one or several regiments. The white coats (or rather light grey) popular amongst many armies soiled easily and had to be pipeclayed to retain any semblence of cleanliness. Green as worn by jagers and rifle regiments proved particularly prone to fading until suitable chemical dyes were devised in the 1890s. The red were the most expensive of the six basic colors and together with white uniforms made the wearers a better target for enemy. “White stood out in the field, when one of the functions was to make a good show. In the course of time coats of blue faded badly, those of pike gray turned a dirty ashen color, and those of green assumed a tinge of yellow, while repairs were all too evident on dyed coats of any kind, and added to a general look of shabbiness. Coats of white, on the other hand, could always be worked up with chalk to make them look ‘new and brilliant.” (Duffy – “Instrument of War” Vol I p 130) The grey uniforms were the cheapest and most practical but were the least attractive. It was not until 20th Century when drab colours were being adopted for active service and ordinary duty wear. The ‘Napoleonic’ coat was called habit à la française, it was dark blue with white lapels for line infantry. The white lapels were treated with pipe clay, which made them really white. In 1793 the dark blue coats were oficially introduced in the infantry. It had long tail that was shortened before 1806. (The weather ‘softened’ the color of the dark blue and dust, blood and mud made it sometimes unrecognizable.) The dark blue became greyish blue etc. In 1800-1801 the coat was given shorter tail and was stated that the collar and cuffs are red piped white. The lapels were white piped red although – according to an order of July 13th 1805 – many colonels didn’t obey this order and have abolished the red piping. According to regulations the coat of line infantry suppose to have red cuffs with dark blue cuff flaps but red cuff flaps were more popular. There were few differences between the coat of line and light infantryman. According to Etat-Militaire (1801) the coat tail of light infantryman was shorter than that of the lineman. In 1806 as a result of the British naval blockade there was a shortage of indigo used for dyeing cloth and so Napoleon ordered the introduction of a white uniform for his line infantry. According to Decree of April 25th 1806 the following regiments of line infantry were assigned white coats: 3rd, 4th, 8th, 12th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, 21st, 22nd, 24th, 25th, 27th, 28th, 32nd, 33rd, 34th and 36th Line. (Journal Militaire Vol I 1806, pp 176-178) Napoleon expressed his disapproval and only 18 of the 112 regiments were issued with these. This is said that it happened after he saw bloodstained white uniforms at Eylau. But to me this reason sounds a little bit strange. The battle at Eylau was fought on a snowy, winter day and soldier wore the warm long greatcoat. If he was wounded the greatcoat, and not the white jacket, was “marked”. Secondly, white uniforms didn’t bother the Austrians, they wore them all the time. It didn’t bother the Saxon soldiers neither. I guess the white color reminded Napoleon the old regime of previous century and therefore he disapproved it. In 1807 the importing of indigo resumed and the dark blue coats were reinstated.

Infantry greatcoat (overcoat)

In April 1806 all soldiers of field battalions (but not the depot, reserve and garrison battalions) received beige, grey, blue and brown greatcoats. There was little standarization but the most common were dull beige and it was the official color. (According to Ordannance du 25 Avril 1806: “La capote ou redingote en drap beige.”) The average French greatcoat was not too long, just below the knee. The Russian greatcoats were longer but climate in Russia was harsher. Usually, French infantry had their greatcoats (introduced officially in late 1806) rolled on the back of their backpacks. They couldn’t wear them rolled over the shoulder as the Russians and Prussians because they were cut differently. For example the Prussian greatcoats were very wide at the bottom. The French ones were narrower and thus, if you rolled them, would have been too short to be carried over the shoulder. Only in 1812 was made first real attempt to standarize the greatcoats so the troops have more military look than civilian crowd. According to Article 21 of the Bardin regulations issued in 1812 all greatcoats for the line and light infantry were made of “beige serge wool.” There were no distinctions between line and light infantry, and even more, there were no distincions between infantry and artillery. All of them were beige greatcoats. Carl Vernet in his book about Bardin Regulations gave grey greatcoats for privates and NCOs in infantry and artillery and dark blue for officers. In 1813 all the numerous gunners of four naval artillery regiments were issued dark blue (not beige) greatcoats. According to Knotel in 1813-1814 campaigns many greatcoats in line and light infantry bore red patches on collars. In the Young Guard the greatcoats were worn over the uniforms. Henri Lachoque writes: “The following order was issued: ‘Coats will be worn under the overcoats. On fine days generals may order the latter rolled over the packs; but in foul or cold weather, or on night marches, soldiers must wear both coats and ocercoats.” (Lachoque – “The Anatomy of Glory” p 304) The infantry of Old Guard continued with the solemn, dark blue greatcoats. The infantry of Young Guard wore dark-grey greatcoats (some say it was blue-grey, with more grey than blue). In 1815 majority of the Young Guard left on campaign wearing dark grey greatcoats with red or yellow epauletes. Minority wore either beige of line troops or dark-blue of Old Guard.

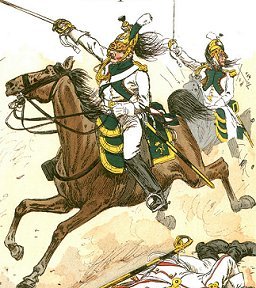

Cavalry greatcoat. (Cloak)

Right: French Chevaulegere Lanciers. (Source: Projet de règlement sur l’habillement du mjr Bardin. Paris, Musée de l’Armée.) . . . The sleeves cloaks looked awesome during charge but not too comfortable when carbines were used. When mounted the greatcoat protected not only the man but also part of the horse, weapons and harness. On a warm day before combat the greatcoat (cloak or capote) was rolled over the shoulder and served as a protection against saber blows and lance thrusts. Ernst Maximilian Hermann von Gaffron of the Prussian Silesian Cuirassiers describes combat with French dragoons in 1813 at Liebertwolkwitz: “The horse-tail manes of their helmets … and the rolled greatcoats, which they wore over their shoulders, protected them so well that they were pretty impervious to cuts, and our Silesians were not trained to thrust nor were our broad-bladed swords long enough to reach them.”

Right: French Dragoons.

|

Headwears. Shakos, Helmets and Bearskins.

Bicorn hat.

The Napoleonic French infantry wore bicorn hats, instead of the tricorn hats of the Royal Army. “When new, it was jaunty and could be slapped into your head at any angle. … A little bad weather however, left the cheap bicorn soggy and drooping forlornly about your ears; whatever the weather, it collected a lead of snow, rain, or dust. Present generations who regard the runty vestige of a shako now worn by the West Point cadets as an instrument of torture might be shocked to realize that this new headgear was considered an excellent innovation. Made of heavy felt and leather or entirely of boiled leather, it protected the soldier’s skull from saber cuts, gun butts, and dropped chamber pots. Its visor shaded his eyes, and its inside was furnished with loops to hold the soldier’s mirror and brushes for his coat, shoes, and hair.” ( Elting – “Swords Around a Throne” p 445)

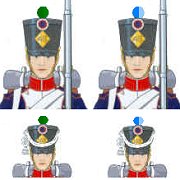

Shako.

In early 1790s the French infantrymen wore the peaked leather helmets, similar to the British “Tarleton”. It was a small cap with a sausage-like device on top. It was replaced with tricorn hats. In early 1800s was introduced shako with cords. The word “shako” originated from the Hungarian name csákó, which was a part of the uniform of Hungarian hussars. From 1800 on the shako became the standard military headress of most regiments in nearly all European armies. It retained this dominant position until the mid 19th century. In 1804 a shako with red cords was prescribed for Napoleonic line grenadiers. The first shako for French infantry was authorized in February 1806 and replaced the bicorn hat by 1807. It was black, had a felt or board body and was widening slightly towards the top. On the front was borned a tricolor cockade above a lozenge shaped brass plate. The top of the shako was waterproofed and had a black leather peak and laces around the top and bottom. Each side of the shako was strengthened by a black leather shevron. On the top of shako was mounted a color pompon or plume. Shako cords: Inside of the shako was space for pompon, cloth cover for shako, spoon, tobacco etc. From 1808 until the end of Napoleonic wars the six companies (1 grenadier, 1 voltigeur and 4 fusiliers) within each battalion were distinguished by color of pompon. There were no battalion identifications on pompons although unoficially solid colored pompon was for all the companies of 1st battalion and pompon with white center was for all the companies of 2nd battalion. In some regiments there was a number in the white center indicating the battalion. Thus red pompon was for grenadiers of 1st battalion, red pompon with white center and number 2 was for grenadiers of 2nd battalion, etc. In November 1810 was introduced a taller shako and brass chinscales. Cords and plumes were abolished although still continued to be worn as the clothing departments kept selling them until December 1812. In 1811 was allowed to wear the plumes only for senior officers. Unofficially the plumes were worn in some regiments by grenadiers and voltigeurs. In few regiments even the fusiliers had their plumes, for example in 3rd Line Infantry it was a blue plume with a red top. More popular than tall plume was the small pompon. In 1812 was introduced a new shako with new plate comprising a crowned eagle atop a semi-circular plate into which the regimental number was cut. The tricolor cocade was partly covered by the eagle’s head. Color shevrons (on side of shako) and laces (around the top and bottom of shako) were introduced for the elite companies: red for grenadiers and yellow (or green in few regiments) for voltigeurs. According to orders issued in 1812 also the cuirassiers replaced their plumes with pompons. In cavalry there were more variations. The official version for eight companies within regiment was: For parade tassels, racquettes (flounders) and white and braided cords were attached to the shako. For parade the brass chinscales were tied over the front of the shako and its pompon. For campaign instead of shako the more comfortable and lighter bonnet de police was worn. If shako was worn in combat the cords and tassels were removed. During campaign or bad weather the shako was protected with cover. The cover protected the shako, plate, cords and cockade from rain, mud, dust and snow. It was made either of black, waterproofed fabric or grey, off-white, white or beige buff cotton or waxed cloth. Some covers were made of leather. In some cases regimental number was painted on it. The pompon was sometimes worn with the shako cover. For battle most often the shako was worn, with or without the cover. (At Waterloo the colonel of the Nassauers decided that the white cloth covers offered to visible a target for French cavalry and he ordered these covers removed.) In battle the brass chinscales were tied up under the chin to keep the shako in place during a run or jump. If battle was fought in cold weather the warm and comfortable pokalem was worn underneath the shako. The plumes were liked by Napoleon, in some early fight, he discovered that the tall color plumes magnified his soldiers’ appearance and caused the enemy to fire too soon and too high. The soldiers like the plumes during parades and generally in peacetime.

Bearskin.

According to the Decree of 1801: The bearskins (some made of goatskin) for grenadiers were re-introduced in 1789. It had red plume, white cords and a brass plate embossed with a flaming grenade. The white cords of line infantry were soon officially replaced with red but the white were more usual. On some plates was regimental number. The official specification for bearskins called for the plate but there were bearskins without plates. (Even in 1815 in the Old Guard). I’m guessing that approx. 55 % of bearskins for the grenadiers had plates and 45 % were without it. Soldiers liked the comfortable headwear. It gave better protection against saber blow than the bicorn hat. The bearskin was more difficult to cut through than shako and had better padding than the helmet. But it was quite expensive and a black waxed cloth was used as protection for bearskin against bad weather. One of the innovations introduced in 1792 was the replacement of bearskin by the bicorn hat during campaign, march etc. while the bearskin was carried in a bag. It suppose to last for 6 years. According to Rousselot in 1804 the bearskins were sometimes given as reward to distinguished line regiments but also to those who simply required them. In July 1805 the foot carabiniers of light infantry regiments were ordered to return their bearskins to regimental depots in preparation “for the coming campaign” and adopt shakos instead. The shorter bearskin became popular among light infantrymen. For example in 1806-1807 some foot carabiniers wore them and by 1809 even some voltigeurs, for example voltigeurs of 10th Light Infantry Regiment and voltigeurs in Oudinot’s famous division. In 1806-1807 campaigns some of the foot carabiniers wore bearskins with red cords and plumes. In 1811 some light infantry regiments retained the bearskins for their foot carabiniers, while other regiments had their carabiniers in busbies or shakos.

In February 1812 the bearskins were officially discontinued in infantry and cavalry due to shortage of bear furs, although some regiments kept bearskins. This process was much smoother in infantry, wherein already long before 1812 many regiments wore shakos instead of bearskins. The grenadiers of line infantry and carabiniers of light infantry were ordered to adopt shakos with red shevrons and upper/lower bands. Few infantry regiments, incl. 46th Line Infantry Regiment, kept their grenadiers in bearskins until 1814. These were without cords and plumes and many were without front plates. Some light outfits also kept bearskins. In February 1812 the elite companies of French hussar and chasseur regiments were ordered to adopt shakos with red shevrons and upper/lower bands. Many hussars regiments and some chasseurs continued with their bearskins until 1815. Actually in the hussar regiments was the highest percentage of bearskins. These flamboyant warriors stubbornly refused any changes. In February 1812 the elite companies of French dragoon regiments were ordered to adopt helmets with red plumes instead of bearskins. Many regiments disobeyed this order and kept bearskins until 1814 and 1815. Officially only the Old Guard wore bearskins. Before the war in 1812 against Russia the Guard horse grenadiers replaced their old bearskins with new ones made by the Emperor’s hatter Poupard. The cords were also replaced with new ones.

|

Other Items. Pelisses, Dolmans, Knapsacks, Haversacks etc. A hussar officer’s uniform … was warranted to make the most down-cheeked lieutenant look like a rider of destiny. … Of course even the most dressed-up Napoleonic regiment might look somewhat sloppy today. It had nu dry cleaning, steam pressing, or detergents to keep it spotless, creased, and sharp enough for a modern sergeant’s approval… “Cavalryman’s uniform accessories recommended by De Brack included a cloth “bellyband” worn under the shirt to give abdominal support during long rides and to protect the stomach from the cold and humidity that doctors thought caused so much sickness. Also, every mounted man should have a suspensoir to guard his “organs of generation” when a sudden movement of his horse slammed his crotch against the pommel …” (Elting – “Swords Around a Throne” p 440, 452)

Infantry’s knapsacks

The Extrait des reglament provisoure pour le service des troupes en campagne stated that French soldiers were not to take off their knapsack when preparing for combat. Sir Charles Oman however reports that the light companies of Darmagnac’s infantry division were ordered to remove and stack their knapsacks: “[D’Erlon] … collected the eight light companies of Darmagnac’s division, ordered them to take off and stack their knapsacks, and launched them as a swarm of tirailleurs at the position of the British on the Aretesque knoll.” The knapsack carried by the Old Guard was larger than the normal infantry issue and had 3 (instead of 2) white closing straps and buckles. Paintings of Waterloo show the French soldiers with their knapsacks on but no greatcoat/blanket roll on top. The haversack was a simple fabric bag slung over the right shoulder. It was primarily used to carry rations.

Light cavalry’s pelisse, dolman

The pelisse was worn in several ways: Most often the fur-edged pelisse was left in depot, or kept boxed, instead only the lighter dolman was worn. They became so damaged already during the first campaign, that they were not taken by the rank and file. The cost of reparing pelisse was high even for the Guard chasseurs that only some officers could afford it. Henri Lachoque writes that in 1807 during a parade in Paris the Guard chasseurs “were wearing undress coats with aiguillettes. The crowd missed their gaudy dolmans and pelisses …” There was also gilet, a sleeveless wool vest braided identical to the dolman. It was worn under the fur-edged pelisse, when the pelisse was worn as a jacket, or under dolman as seen on the picture above. The gilet was also worn in the camp with the shirt. In France, especially in early Empire, the pelisse and dolman were aslo used by some chasseurs-a-cheval. Originally only officers and NCOs in chasseur regiments wore pelisse but then also the rank and file of 5th, 10th and 22nd regiment adopted them. The chasseurs also wore dolmans although these items were never manufactured for them during Empire. In 1804 all chasseurs were ordered to give up their dolmans for plain coats but the Frenchmen loved flamboyant outfits and in 1805 almost chasseur regiments continued wearing them. The dolman and pelisse (plus sash and sabretache) were worn by chasseurs mainly for parade and only seven regiments wore them for field service. During 1806-1807 campaigns vast majority of chasseurs were without pelisses. They were not taken on campaign. Some pelisses were left in regimental depots while others were used up and replaced by the simpler and cheaper green coat. The Guard chasseurs wore pelisses until 1805 campaign and at Austerlitz (worn over dolmans). During every next campaign only officers and some NCOs wore them. The sabretaches were used by hussars (and some chasseurs in early Empire). It was a leathern case for papers, raports, small items etc. and was suspended by straps from hussar’s belt at the left side. During campaign the ornamented sabretaches were covered by plain black oilcloth (see picture). During campaigns in 1813, 1814 and 1815 the sabretaches became rare sight, and the few still existing were less colorful than those in 1804-1808.

The sheepskins were very comfortable in winter. The problems with them were in summer, they were hot to ride on and in rain they “soaked like sponges”. To make things worse, a lot of humidity and water made the sheepskins badly roting. Pictures: French chasseur (left) and French dragoon (right). Please notice the difference in size and shape of their saddle-covers. |

1812 – 1815 Bardin Regulations. 1812 – 1815 Bardin Regulations.New and more modest uniforms were introduced.  Up to the beginning of XIX Century military fashions remained in many ways indebted to civilian models. It was not until 1812 when Colonel Bardin wrote “It is necessary that the military dress don’t follow the liberties and whims of civilian fashion. Military styles are not the same with women fashion.” Napoleon liked Bardin’s view very much and accepted his ideas at once. As a result new and more modest uniforms were introduced. Up to the beginning of XIX Century military fashions remained in many ways indebted to civilian models. It was not until 1812 when Colonel Bardin wrote “It is necessary that the military dress don’t follow the liberties and whims of civilian fashion. Military styles are not the same with women fashion.” Napoleon liked Bardin’s view very much and accepted his ideas at once. As a result new and more modest uniforms were introduced.

The new uniform regulations were issued in 1812 are commonly referred to as the Bardin Regulations. (Colonel Bardin’s ‘Regulations in the Fitting out of Soldiers of the French Army’, 1812.) The Old and Middle Guard were not affected by the Bardin Regulations as they had their own uniform regulations separate from the army troops. The new infantry uniform included two major changes : According the Bardin regulations there were only the following outfits for the line and light infantry:

|

Campaign, Battle and Parade Dress. Campaign, Battle and Parade Dress.“The splendid colors of contemporary battle scenes are misleading, in reality the colors of most scenes of carnage must have been a dirty grey-brown. ” (source: “Battledress. The Uniforms of the World’s Great Armies 1700 to the Present.” p 133)  Picture: three types of uniforms, parade uniform, campaign uniform, and uniform worn in battle. Napoleon’s Guard Foot Artillery. Slightly modified uniforms after Andre Jouineau. Picture: three types of uniforms, parade uniform, campaign uniform, and uniform worn in battle. Napoleon’s Guard Foot Artillery. Slightly modified uniforms after Andre Jouineau.

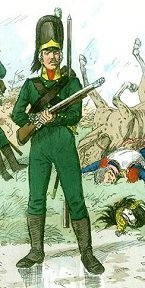

There were notable differences between the uniforms worn during parades and on campaigns. The soldier on campaign was likely to present a shabby and non-descript appearance as unsuitable peacetime dress quickly deteriorated. They suffered from a lack of proper clothing, and homemade replacements and captured items resulted in variety of colors and materials within a single battalion. Instead of the elegant breeches and gaiters the infantryman wore trousers, his shako was protected with special cloth cover, the greatcoat was rolled and attached on the knapsack, etc. In 1807 General Lasalle wrote: “Who could recognize the brilliant hussars from Kronach fourteen months ago, those of the 5th Regiment with their white pelisses with lemon-yellow braids and their sky-blue breeches, those of the 7th Regiment with their green pelisses with daffodil-yellow braids and their scarlet breeches ? Today the whole brigade, men and horses adorned alike in mud, have neither form nor color. Their uniform is misery.” “For lack of shakos the 14th Light Regiment would fight the Waterloo campaign in fatigue caps.” (Britten-Austin “1815 the return of Napoleon” p 295) The dyes were primitive and different batches of uniforms worn by the same unit presented differing shades, especially after exposure to rain and sun. The appearance of soldiers in battle was intended to impress and intimidate the enemy. In ancient wars the barbarians of today Germany piled their hair on the tops of their heads to make themselves look taller. During Napoleonic Wars the dragoons and cuirassiers wore helmets with heightened crests and combs and attached horsehair tails. The bearskins worn by the Old Guard, Scottish highland units and grenadiers employ the same principle. Prussian hussars wore the “skull and crossbones” Totenkopf on their hats. Very often the enemy realized that the Roman legionares got serious because they wore their finest equipmet. Intimidating appearance played role in the collapse of morale of good troops. For example in 54 BC the Roman legionaries were put to flight by the frightening appearance of the Galls before their final attack. Napoleon’s troops were no different. The sight of the troops on the battlefield however was often obscured by building, hill or trees. But if there was a good weather and open terrain the troops were recognized at 1500 m, the cavalry was distinguished from infantry at 1200 m, and the bigger details of uniforms (crossbelts, headwears) were distinguished at 600 m. At 225 m officers can be recognized and uniforms seen clearly. In 1809 at Sacile the French 8th Chasseurs-a-Cheval was full of swaggering men who had bragged about their exploits. They wore in battle their full dress uniform (parade uniform) so as to stand out during the battle. Unfortunately they were routed by Austrian hussars and fled toward the river. It amused the poorly dressed French infantrymen. Other cavalry regiments charged to drive off the pursuing Austrians. What the soldiers actually wore in battle depended on several factors: Before entering a city the troops often wore parade dress. “As I rode to the castle at Schoenbrunn, I passed the heads of the columns of Oudinot’s combined grenadiers and voltigeurs, who were already done up in full dress, with plumes in the headgear ready for the triumphant entry into Vienna.” (Chlapowski – “Memoirs of a Polish Lancer” p 64, translated by Tim Simmons) The infantry of Old Guard wore their parade dress in 1809 at Wagram. In 1812 when the army had to cross Niemen River and border with Russia it was ordered that all regiments wear the parade uniforms. Already in early morning (4 AM) of that day Planat de la Faye saw “the army in parade uniforms, begins defiling in good order on to the 3 bridges.” According to Fezensac in 1812 at Borodino all the regiments “had been given orders to put on their parade uniforms.” Though their uniforms were often as dirty and worn as the other hard-marching troops, the men of the Guards were noted for their attention to appearance and soldierly bearing. Below is a list of battles and how the French Imperial Guard was dressed.

|

Napoleon’s Uniform. Napoleon’s Uniform.Napoleon contended himself with a simple hat and dark green uniform. On sundays and grand events Napoleon wore dark blue uniform with white lapels of a Colonel of the Guard foot grenadiers (grenadiers-a-pied de la garde). For example in 1804 on sundays in Camp of Boulogne, in 1806 when he meditated for some time at the tomb of Prussian King Frederick the Great, in 1807 while meeting with Polish officials, etc. The uniform of colonel of Guard horse chasseurs (chasseurs-a-cheval de la garde) was for daily use, during campaign, march etc. When in 1812 Napoleon appeared at Kovno (Lithuanian-Russian border) he wore uniform of a Polish officer. At the outposts Napoleon disguised himself – in 1809 on Lobau Island he had turned up, borrowed a light infantryman’s grey overcoat and shako and, thus attired, had done sentry duty on the river bank to examine the Austrian positions as close quarters. On 24th January 1814 in Paris the Emperor wore the uniform of the commander in chief of the National Guard, and received the officers of the Paris garrison. “It was his last night in Paris.” (Lachoque – “The Anatomy of Glory” p 342) While Napoleon was dressed in a very modest way, his marshals and Guard officers’ uniforms were loaded with gold lace. In 1809 painter Adam wrote: “There he sat on his little white Arab horse, in a rather careless posture, with a small hat on his head, and wearing the famous dust-grey cloak, white breeches and top boots, so insignificant-looking that no one would have recognized the personage as the mighty Emperor-the victor of Austerlitz and Jena before whom even monarchs must bow-if they had not seen him represented so often in pictures. His pale face, cold features, and keen, serious gaze made an almost uncanny impression on my mind, while the glitter of the many uniforms which surrounded him heightened the contrast of his inconspicuous appearance.” |

Sources and Links.

Recommended Reading.

Plates – Projet de règlement sur l’habillement du mjr Bardin. Paris, Musée de l’Armée.

L’Armee Francaise: An Illustrated History of the French Army, 1790-1885

Rousselot – “Napoleon’s Elite Cavalry: Cavalry of the Imperial Guard, 1804-1815”

Charmy – “Splendeur Des Uniformes De Napoleon: Cavalerie”

Elting – “Napoleonic Uniforms” (superb book)

Elting – “Swords Around a Throne”

Chlapowski – “Memoirs of a Polish Lancer” (translated by Tim Simmons)

Haythornthwaite – “Uniforms of Napoleon’s Russian Campaign”

Vernet – “Uniforms of Napoleon’s Army”

Hourtoulle – “Soldiers and Uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars”

Bukhari, McBride – “Napoleon’s Cuirassiers and Carabiniers”

Olivier Schmidt, Germany

K. Smith , USA

Jouineau and Mongin – “Officers and Soldiers of the French Imperial Guard 1804-15” Vol I (The Foot Soldiers)

Military Uniform.

Pictures of French Uniforms.

Imperial German Uniforms 1842 to 1918.

History of the shako and the spiked helmet.

Pelisse.

Uniforms of British Hussars: “Chase me Ladies, I’m in the Cavalry !”

Linen comes in a variety of natural shades that range from light to dark. Linen may be dyed, but the range of colors is much less vivid than for the wool colors.

Linen comes in a variety of natural shades that range from light to dark. Linen may be dyed, but the range of colors is much less vivid than for the wool colors. Color of linen can range from bleached snow-white to silver, ecru, brown or beige. Linen can be either soft or heavier and harder. Its greatest feature is that it can absorb moisture more quickly than cotton and move this moisture faster so that the drying time is shorter.

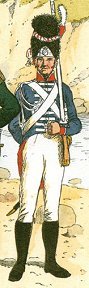

Color of linen can range from bleached snow-white to silver, ecru, brown or beige. Linen can be either soft or heavier and harder. Its greatest feature is that it can absorb moisture more quickly than cotton and move this moisture faster so that the drying time is shorter. For the French light infantry the undercoat was white linen in summer and blue wool in winter. The white woolen waistcoat was treated with chalk, which was said to have “burned” (brûlé) the cloth. See picture –>

For the French light infantry the undercoat was white linen in summer and blue wool in winter. The white woolen waistcoat was treated with chalk, which was said to have “burned” (brûlé) the cloth. See picture –> The waistcoat of

The waistcoat of  Picture: dark blue coat with dark blue shoulder straps piped red, red collar and cuffs pipped white, white lapels, white undercoat, and white shoulder belt. The

Picture: dark blue coat with dark blue shoulder straps piped red, red collar and cuffs pipped white, white lapels, white undercoat, and white shoulder belt. The  In January 1812 was introduced so-called habit-veste, a coat with even shorter tail (officers’ tails were slightly longer). Its white turnbacks bore a blue crowned “N” for fusiliers, red grenade for grenadiers and yellow horn for voltigeurs.

In January 1812 was introduced so-called habit-veste, a coat with even shorter tail (officers’ tails were slightly longer). Its white turnbacks bore a blue crowned “N” for fusiliers, red grenade for grenadiers and yellow horn for voltigeurs. Life during campaign had a variety of conditions and experiences for the cavalrymen. There were great hardships undergone, and the weather had the greatest influence on conditions, varying from heat to extreme cold. The main protection against rain and snow was one’s greatcoat. It was popular and comfortable voluminous wear and could be worn with or without the coat underneath. Many troops wore civilian overcoats, capes and cloaks. Some greatcoats (overcoats) were purchased by individual soldiers, NCOs and officers. One of the innovations introduced in 1792 was sky-blue greatcoat for officers. It was not until 1805 that the were greatcoats issued to the troops. They were purchased not by individuals but from regimental funds.

Life during campaign had a variety of conditions and experiences for the cavalrymen. There were great hardships undergone, and the weather had the greatest influence on conditions, varying from heat to extreme cold. The main protection against rain and snow was one’s greatcoat. It was popular and comfortable voluminous wear and could be worn with or without the coat underneath. Many troops wore civilian overcoats, capes and cloaks. Some greatcoats (overcoats) were purchased by individual soldiers, NCOs and officers. One of the innovations introduced in 1792 was sky-blue greatcoat for officers. It was not until 1805 that the were greatcoats issued to the troops. They were purchased not by individuals but from regimental funds.

Left: French 9th Hussar Regiment. (Source: Projet de règlement sur l’habillement du mjr Bardin. Paris, Musée de l’Armée.)

Left: French 9th Hussar Regiment. (Source: Projet de règlement sur l’habillement du mjr Bardin. Paris, Musée de l’Armée.)

Left: French Horse Grenadiers of Imperial Guard.

Left: French Horse Grenadiers of Imperial Guard. Picture: bicorn hats of French line infantry in 1806.

Picture: bicorn hats of French line infantry in 1806. Picture: shakos of French line infantry (fusiliers), by Andre Jouineau.

Picture: shakos of French line infantry (fusiliers), by Andre Jouineau. Picture: bearskins of French infantry. Carabinier (left) and grenadier (right).

Picture: bearskins of French infantry. Carabinier (left) and grenadier (right). This is said that the trumpeters of cavalry regiments wore white bearskins. Rousselot however claimed that during campaign the trumpeters of Guard horse chasseurs (chasseurs-a-cheval de la Garde) and Guard horse grenadiers (grenadiers-a-cheval de la Garde) left their white bearskins in regimental depots.

This is said that the trumpeters of cavalry regiments wore white bearskins. Rousselot however claimed that during campaign the trumpeters of Guard horse chasseurs (chasseurs-a-cheval de la Garde) and Guard horse grenadiers (grenadiers-a-cheval de la Garde) left their white bearskins in regimental depots. Picture: French fusilier (line infantry) wearing off-white trousers over his white breeches and white gaiters. Picture by Dmitriy Zgonnik of Ukraine for the H.A.T. Company.

Picture: French fusilier (line infantry) wearing off-white trousers over his white breeches and white gaiters. Picture by Dmitriy Zgonnik of Ukraine for the H.A.T. Company.

Before campaign every heavy and light cavalryman received white sheepskin to the regulation shabraque (cloth covering the saddle) and grey overalls called pantalons a cheval. The overalls were worn with or without the breeches underneath. Some overalls had cloth covered buttons down the outer seams while other had red laces instead of buttons. The first time the overalls were mentioned in official order was in the year of 1812 although they were used already in the 1790s. The decree of 1812 described the overalls as made of grey linen with cloth covered buttons. Due to its weight and numerous buttons this type of overalls was replaced by lighter overalls, often reinforced on the inside of the legs and around the bottoms with black leather. These lighter overalls might be grey, blue, red or green but during 1812-1815 the grey with orange or red stripe and without buttons were more common.

Before campaign every heavy and light cavalryman received white sheepskin to the regulation shabraque (cloth covering the saddle) and grey overalls called pantalons a cheval. The overalls were worn with or without the breeches underneath. Some overalls had cloth covered buttons down the outer seams while other had red laces instead of buttons. The first time the overalls were mentioned in official order was in the year of 1812 although they were used already in the 1790s. The decree of 1812 described the overalls as made of grey linen with cloth covered buttons. Due to its weight and numerous buttons this type of overalls was replaced by lighter overalls, often reinforced on the inside of the legs and around the bottoms with black leather. These lighter overalls might be grey, blue, red or green but during 1812-1815 the grey with orange or red stripe and without buttons were more common. Right:

Right: Left:

Left: Right:

Right: The knapsack was made of cow or goat skin with the hair on the outside. It contained a lot of essential personal items from which the soldier had no desire to be separated. The water bottle hung behind the left hip rather than the right to avoid obstructing the opening of the cartridge box.

The knapsack was made of cow or goat skin with the hair on the outside. It contained a lot of essential personal items from which the soldier had no desire to be separated. The water bottle hung behind the left hip rather than the right to avoid obstructing the opening of the cartridge box. The dolman and fur-edged pelisse were heavily braided parts of hussar’s flamboyant outfit. The pelisse cost a little fortune, 216 Francs !

The dolman and fur-edged pelisse were heavily braided parts of hussar’s flamboyant outfit. The pelisse cost a little fortune, 216 Francs !

Before campaign the white sheepskin trimed red and grey overalls were issued to every cavalryman. The sheepskins for light cavalry were bigger than for the heavies. They were used by French, Polish and Austrian cavalry (but not by the Russians and Prussians) for comfort, especially during long marches.

Before campaign the white sheepskin trimed red and grey overalls were issued to every cavalryman. The sheepskins for light cavalry were bigger than for the heavies. They were used by French, Polish and Austrian cavalry (but not by the Russians and Prussians) for comfort, especially during long marches. The new uniforms were probably issued in 1812 only to Davout’s I Army Corps before the invasion of Russia. Koen de Smet wrote: “The Bardin uniform was introduced in 1812, and some units (or parts of units) will certainly have received it before the Russian campaign. The majority however will still have started the Russian campaign in their old uniforms.” But this is not certain at all, rather they were not issued in any larger quantity until Spring 1813 and only on the primary theater of war (great battles in Germany: Leipzig, Hanau etc.) French troops on secondary theaters of war, in Italy and Spain, wore the old uniforms.

The new uniforms were probably issued in 1812 only to Davout’s I Army Corps before the invasion of Russia. Koen de Smet wrote: “The Bardin uniform was introduced in 1812, and some units (or parts of units) will certainly have received it before the Russian campaign. The majority however will still have started the Russian campaign in their old uniforms.” But this is not certain at all, rather they were not issued in any larger quantity until Spring 1813 and only on the primary theater of war (great battles in Germany: Leipzig, Hanau etc.) French troops on secondary theaters of war, in Italy and Spain, wore the old uniforms.