This article, “The End Of An Era: Winchester Closes New Haven,” appeared originally in the May 2006 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

Recently, it has become fashionable for some residents of Connecticut to refer to their home as “the munitions state.” It should be noted that the phrase is not meant as a compliment, but rather, quite the opposite. In the eyes of those who use the epithet, Connecticut’s involvement in the production of arms is something shameful and not worthy of commemoration in any fashion.

Yet, a scant six decades ago, Connecticut’s arms industry played a pivotal role in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call to transform the United States into an “Arsenal of Democracy.” Firms such as Colt, High Standard, Marlin and Winchester went on to produce the pistols, machine guns and rifles that brought about the destruction of the Axis Powers. Two-and-a-half decades earlier, it was Connecticut’s arms factories that helped the Allies defeat the forces of Imperial Germany. Earlier still, it was the manufacturing capabilities of Connecticut that ensured the victory of Union forces over those of the rebellious South.

Given their contributions to the security of the United States, it is saddening to see once-great companies fade from the scene. The sense of loss is made even more acute when present-day witnesses have little regard for the historical significance of these firms.

Winchester’s involvement with New Haven goes back to 1856. This view of the New Haven Arms Co. factory, circa 1860, shows Oliver F. Winchester in the window and Benjamin Tyler Henry in the doorway.

The latest factory to close in Connecticut has a tradition spreading back over one-and-a-half centuries. Though now owned by the U.S. Repeating Arms Co., the factory located in New Haven is almost universally referred to as the Winchester Repeating Arms Co. factory due to its long operation under that name.

The New Haven works has produced millions of small arms for both the government and private use over the years. As a result, it is now worth remembering the significance its contribution to the welfare of this country and to the fabric of our culture.

The present-day facility occupies land first used as an arms and ammunition plant in 1872. However, Winchester’s involvement with New Haven goes back even further. In 1856, Oliver F. Winchester established a small factory in New Haven to manufacture Volcanic-pattern pistols and rifles. This firm, operating under the name New Haven Arms Company, later went on to produce the famous Henry Repeating Rifle.

During the Civil War, Henrys were purchased both by the U.S. government and by individual soldiers who recognized their tactical value. Christened by Southerners as “the damned Yankee rifle you can load on Sunday and shoot all week,” the Henry played an important role in the Union’s eventual victory.

Following the Civil War, the Henry’s design was modified so that it could be loaded through a gate on the right side of the receiver. Although this feature was designed by Nelson King, the new brass-frame rifle introduced in 1866 was briefly known as the Improved Henry before it became simply known as “the Winchester” after its manufacturer.

The Winchester rapidly gained an audience among frontiersmen and sportsmen who appreciated its reliability and its ability to fire 13 shots without reloading. During the early 1870s, improvements in ammunition design, as well as manufacturing, led Winchester to develop a new iron-frame, repeating rifle chambered for a center-fire .44-40 Win. cartridge that was ballistically far superior to the rimfire round used in the 1866.

When the Model 1873 entered the market, it was immediately embraced by settlers, sportsmen and Western lawmen, especially the Texas Rangers. Despite its identification as “the gun that won the West” in a 1919 advertisement, most purchasers of the Model 1873 lived on the eastern side of the Mississippi River, where it was a well-respected deer rifle. In 1878, Winchester introduced its first bolt-action rifle, known as the Winchester-Hotchkiss. While the U.S. government purchased a considerable number of the rifles for both the Army and Navy, public acceptance was lackluster.

“I Wish I Had Dad’s Winchester” by Eugen Ivard. Courtesy of Winfield Galleries.

The Winchester company’s survival during the late 1860s and ’70s, when many other arms manufacturers failed, was the direct result of its founder’s decision to pursue foreign sales. Oliver F. Winchester’s realization at the end of the Civil War that the profitability of his firm would depend upon the development of overseas markets was prophetic.

By deploying agents throughout the world, he was able to secure not only government contracts for his arms but, more importantly, protective import legislation that prevented other companies from directly selling their wares to retailers in a number of lucrative markets. This business plan was followed and further refined after Winchester’s death in 1880.

Though lever-action rifles remained a mainstay of the Winchester product line, in 1883, the firm entered into an alliance with John Moses Browning that would expand its model line. Over the next two decades, 10 Browning designs—incorporating improvements developed by the firm’s senior designer, William Mason—were manufactured by Winchester. Among these were two of the most famous rifles to be produced: the Model 1886 and 1894.

In addition, Browning created what was to become known as the Model 1897 slide-action shotgun. The value of Browning’s contributions to Winchester is best demonstrated by the fact that the Model 1894 remained in production through the date that the modern plant was slated for closure.

One firearm made during that period, not normally associated with the Winchester company, is the Model 1895 Lee straight-pull rifle. Chambered for the 6 mm high-velocity cartridge, the Lee was adopted by the U.S. Navy. Its use by the U.S. Marines guarding the consular area in Beijing during China’s Boxer Rebellion brought the rifle to public notice. In newspaper accounts published after the event, the Lee’s effectiveness was given equal prominence to the valor of the Marines themselves.

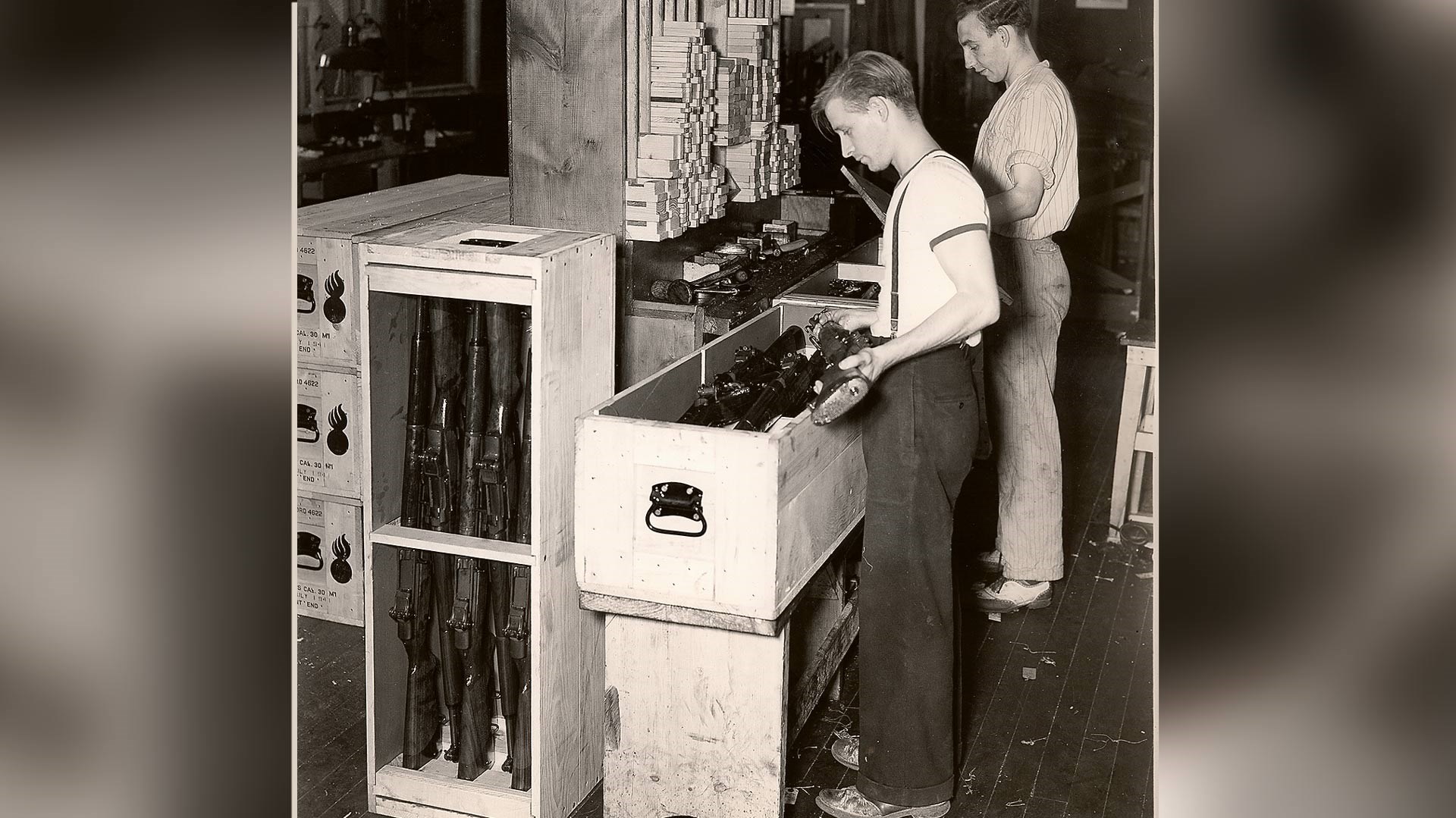

During World War II, Winchester was the only private manufacturer of M1 Garand rifles. The firm made more than a half-million M1s.

Following the end of Browning’s collaboration with Winchester in 1903, a young designer hired by Mason was to guide the firm’s product development for the next 30 years. In fairly rapid succession, Thomas C. Johnson expanded the Winchester line by developing the Model 1903, 1905, 1907 and 1910 self-loading rifles as well as the Model 1912 shotgun. Though work was forestalled by World War I, Johnson was also responsible for the Model 52 bolt-action and prototypes for what was later to become the Model 70—the “Rifleman’s Rifle.”

While the United States did not enter World War I until 1917, Winchester’s involvement began in late 1914. It manufactured more than a half-million Pattern 14 Rifles for the British, as well as approximately 273,000,000 rounds of .303 ammunition and nearly 2 million artillery shells. In addition, the French and Imperial Russian governments purchased quantities of the Model 1907 and 1910 self-loading rifles. Once America joined the war in April 1917, the Winchester company immediately offered its facilities to the War Department.

The first arm to be produced under this arrangement was the Model of 1917 rifle, of which 545,566 were manufactured. Later, the firm received a contract for the Browning Automatic Rifle and had the distinction of being the only manufacturer to deliver BARs in time for use in France. Among the other arms developed during World War I by Winchester’s designers was a dual magazine, selective-fire rifle that presaged the modern assault rifle. Chambered for a short, straight-cased .345 round, this rifle was fitted with easily detachable barrels that allowed its use as either an infantry or aerial arm.

Following World War I, Winchester’s management decided to expand operations to include hardware and general sporting goods. This move was prompted in part by Kidder-Peabody, which had become one of the concern’s primary stockholders. Although the arrangement briefly held promise, by the mid-1920s, it had become evident that the firm was rapidly failing. Eventually, it declared bankruptcy but was saved from extinction by the Olin family, owners of the Western Cartridge Company.

Under the Olins’ stewardship, Winchester’s product line was trimmed and emphasis was placed once again on the manufacture of arms and ammunition. Though the 1930s were lean years for the firm, it streamlined its manufacturing and experimented with specialized tool production.

One of the latter programs involved the manufacture of the tooling necessary to make U.S. M1 Rifles. The so-called Educational Contract was a program designed to give the firm a head start on the model’s construction when World War II broke out. Indeed during World War II, Winchester was to be the sole private contractor for this infantry rifle, producing more than half a million of them before the war’s end.

Women played a key role in producing arms for America during World War II. This image shows Winchester’s Helen Wilsznski and others making Garand lock components.

Winchester’s designers were also responsible for what was to become known as the U.S. M1 carbine. The first prototype for this lightweight arm was made in 13 days, and a second, improved version was completed in 30 days. Though Winchester was not the prime contractor, it nevertheless went on to make 699,469 carbines that were to see extensive service in both the European and Pacific Theatres of Operation.

As at the end of World War I, the firm entered a period of retrenchment between 1946 and 1950. The time was not spent idly, however. New models and manufacturing techniques were developed. Experiments were also carried out to determine the value of new materials such as plastics and fiberglass.

To reduce production costs, the firm decided in the early 1960s to simplify its manufacturing processes once again. Adopted in 1964, the changes hurt the company’s image and the public began to classify many product lines as either pre- or post-’64.

Despite these cost-cutting efforts, Winchester’s profitability remained marginal. Consequently, when a labor dispute resulted in a walk-out in 1980, the Olin Corporation decided it was time to divest itself of the Winchester firearm line. In 1981, the New Haven facility was sold to a new firm that took the name U.S. Repeating Arms Co. In turn, this concern was later purchased by the Browning Arms Company, a subsidiary of the Belgian firm, the Herstal Group.

As this is written, however, the New Haven facility is to permanently close, thus ending a century-and-a-half tradition of military and sporting rifles being made in that city. While this a sad event, the contributions of the Winchester factory to the security of this country and the pleasure that its products have given generations of sportsmen must be remembered. In doing that, we do honor to the countless thousands of men and women who spent their energies producing what many have called “the finest rifles in the world.”