When the United States entered World War I during the spring of 1917, our armed forces were woefully lacking in many types of arms and war materiel. One of the bright spots in Uncle Sam’s arsenal, however, was the superb Model of 1911 .45 ACP pistol. Unfortunately, there weren’t nearly enough in the government’s inventory to meet the rapidly growing demand. The U.S. military needed many more handguns—and needed them in a hurry.

At the time of America’s entry into the war, the only manufacturer of the M1911 was the Colt Patent Firearms Mfg. Co. Springfield Armory had manufactured 25,767 M1911 pistols from Fiscal Year 1914 to 1917, but the Armory was too burdened with increased manufacture of the Model of 1903 rifle and other arms to resume making the pistols.

Plans were formulated to have other commercial concerns produce M1911s under contract, but it was recognized that the lag time required for the firms to start manufacturing would result in a serious shortage of handguns at a very critical time. The Ordnance Dept. had to look elsewhere for handguns that could be procured as soon as possible to arm the burgeoning number of troops.

The two major manufacturers of handguns in the country at the time, Colt and Smith & Wesson, both had large-frame revolvers in their product lines with production tooling and trained workers available to manufacture their guns under government contract. The Colt revolver was the “New Service,” and the company had previously manufactured a version of this .45 Colt revolver for the U.S. government, the Model of 1909, but it saw very limited service and was soon superseded by the M1911. The Smith & Wesson revolver was the Second Model .44 Hand Ejector.

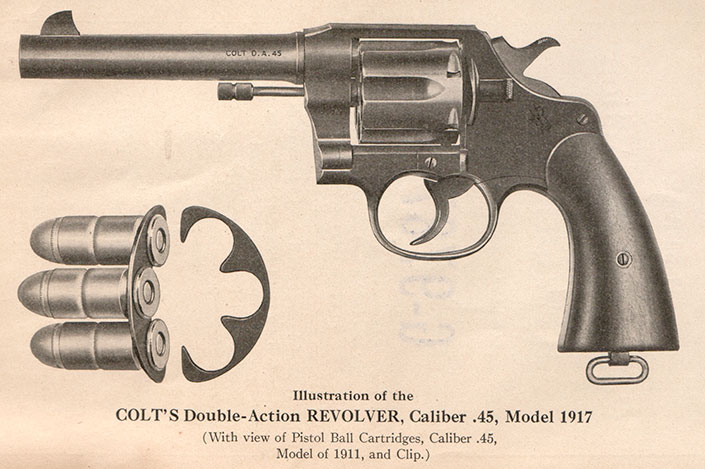

In order to reduce supply and logistical problems, it was mandatory that any revolvers produced under military contract be chambered for the standard .45 ACP cartridge, but neither company had yet offered its revolvers in that chambering. To accommodate the rimless .45 ACP, it was necessary to devise some method of positioning cartridges in the cylinder. Otherwise, the rimless cartridges could not be fired or ejected from the cylinders that were originally designed for rimmed cartridges.

Smith & Wesson re-designed its cylinders to incorporate a shoulder to hold the .45 ACP round in place so it could be fired, but the expended cases had to be manually extracted. To solve this problem, S&W devised an ingenious “half-moon” sheet metal clip that held three cartridges, each properly positioned in the cylinder.

Two of the clips were loaded into the cylinder and the expended cases could be easily ejected. Unlike the S&W revolver, the Colt gun did not initially incorporate the shoulder, which required the “half-moon” clips be used for both firing and ejecting the rounds. An Ordnance Dept. report described the “half-moon” clips:

“A semi-circular clip holding three cartridges, permitted the use of the rimless automatic cartridges in the M1917 Revolver. Without the clip, fired cartridges could not be ejected simultaneously from all six chambers as with the rim type .45 Colt Cartridge. By using these clips, instead of the slower operation of inserting six cartridges singly, the revolvers’ rate of fire was materially increased.”

The Colt and S&W revolvers were adopted as the “Model of 1917.” As was the case with the products of both companies, the M1917 revolvers were well-made and dependable. Except for the hammers and triggers, the external metal parts were blued. As an accommodation to an increased production rate, the final polishing was eventually omitted on the Colt-made revolvers, and the result was a “brushed blue” finish. The revolvers made by both firms were fitted with smooth walnut stocks and a lanyard ring. The nomenclature markings and serial number were stamped on the butt.

The M1917 revolvers were carried in the same pattern of leather holsters as the Model 1909 revolvers, and new holsters manufactured during World War I retained the Model 1909 nomenclature. The gun was positioned in the holster with the butt forward, as was the preference of cavalry troopers. Canvas pouches were fabricated that could be fastened to the standard pistol belt and would accommodate three sets of two “half-moon” clips (total of 18 rounds).

Smith & Wesson delivered the first M1917 revolvers the first week of September 1917, and the Colt guns followed on Oct. 24, 1917. The book America’s Munitions–1917-1918, authored by Assistant Secretary of War Benedict Crowell, indicates that S&W manufactured 153,111 M1917s and Colt made 151,700 for a total of 304,811. However, these numbers do not include revolvers manufactured after Dec. 31, 1918.

As was the case with many other World War I government contracts, the manufacturers were permitted to remain in production into early 1919 so as to utilize existing raw materials previously ordered. This helped mitigate the financial hardships that would have resulted from an abrupt cut-off of the contracts. Most of the contracts contained a provision that the manufacturers would be reimbursed for any arms “in process” at the time of cancellation, thus it made sense for the manufacturers to complete them rather than for the government to pay for half-finished guns. A post-World War I Ordnance document dated Jan. 5, 1924, indicates that the total production of M1917 revolvers was 318,432, which includes the guns produced into early 1919.

The M1917s provided yeoman-like service during the war and proved to be reliable and effective military handguns. Following the Armistice, the M1911 remained the standardized U.S. military sidearm, but M1917s continued to play a supporting role between the wars.

Due to the fact that many of the M1917 revolvers saw extensive use in World War I, a number required re-building and refurbishment. It is reported that the Augusta Arsenal (Georgia) re-built 1,000 S&W revolvers in 1919-1920. Other ordnance facilities, including Rock Island Arsenal, also re-built some of these revolvers, but most of the overhaul work was done by Springfield Armory.

Due to the corrosive-primed ammunition of the period, the most common repair to Model 1917 revolvers was barrel replacements. Springfield Armory actually went into production of new barrels for Colt M1917 revolvers for a period of time. Typically, when a pistol or revolver, indeed almost any gun, was re-built by the military, the initials of the facility were stamped on the gun after the work was completed. The most commonly seen markings of this type found on the M1917 revolvers re-built after World War I were “SA” (for Springfield Armory), “RIA” (Rock Island Arsenal) and “AA” (Augusta Arsenal).

The M1917 revolvers saw little actual service use in the 1920s and 1930s. A number of Model 1917 revolvers were retained by the National Guard, and others were supplied to several governmental agencies, especially the Post Office. In the early 1920s, a rash of brazen, and sometimes quite violent, armed robberies of U.S. Post Office trains, trucks and facilities resulted in a number of U.S. Marines being called into service as “mail guards.”

Some of the Marines, as well as a number of postal employees, were armed with M1917 revolvers. The Marines also utilized M1911 pistols, M1903 rifles, 12-ga. “trench guns,” M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles and, later, Thompson submachine guns. Eventually, the mail robbery sprees were quelled and the Marines were withdrawn from such duty.

M1917 .45 Revolvers In World War II

As it became increasingly probable that the United States would be drawn into the war that erupted in Europe in 1939, the War Dept. evaluated existing military arms in Uncle Sam’s arsenal. One of these, of course, was the M1917 revolver. After the debacle at Dunkirk, a number of arms in our inventory were sent to the British to replace those lost in France. Among these were about 20,000 M1917 revolvers sent to Great Britain circa 1940-41.

After Pearl Harbor, there was a rush to procure all sorts of additional arms, and handguns were no exception. Production contracts for M1911A1 pistols were given to several American manufacturers. However, as was the case a quarter-century earlier, there was a lag time between issuance of the contracts and delivery of the new pistols. Once again, the Colt and S&W M1917 .45 ACP revolvers ably filled a void in America’s small arms arsenal.

Even though many of these revolvers had been overhauled in the 1920s and 1930s, a number of the guns still required refurbishment before they could be issued for use in World War II. Springfield Armory records indicate that 10,263 S&W and 4,017 Colt M1917 revolvers were re-conditioned in 1941. Additionally, quantities of replacement parts for both models were purchased for future overhaul requirements.

The issuance of the Model 1917 revolvers during World War II was discussed in an Ordnance publication: “Again, the M1917 Revolver was called upon as a substitute weapon. On Nov., 1, 1940, there was a total of 188,120 Revolvers M1917 in the field or in stores. Of these, 96,530 were of Colt manufacture and 91,590 Smith and Wesson. It was intended that the use of these weapons be restricted to the Continental United States, but 20,995 Revolvers actually got into combat theaters, due to shortage of M1911A1 Pistols. Primarily, the M1917 was issued to Military Police personnel, within the United States.”

In the book, GI–The Infantryman In World War II, Robert Rush cited the use of these revolvers during training at Camp Wheeler, Ga., in March 1942:

“Next came pistol familiarization. The recruits were handed a M1917 .45 cal. Smith & Wesson revolver, shown how to aim, and with the admonition not to flinch because ‘it was nothing but a gun,’ they fired their 20 rounds at targets positioned 15 and 25 yards away … .”

Many of the M1909 leather holsters dating from World War I continued in use during World War II with the M1917 revolvers. During World War II, a version of the holster that held the revolver with the butt to the rear was adopted and designated as “Holster, Revolver, Cal. .45, M2.”

Even though many more M1911/M1911A1 pistols were used during the war, the almost 21,000 M1917 revolvers that were issued to troops in overseas combat zones saw their fair share of action. While most would probably have preferred a M1911A1 pistol over a M1917 revolver, the latter an had its proponents. One of the more enthusiastic of these was Pvt. Richard Lyman, a paratrooper with the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team. As related in the Gerald Astor’s book, Battling Buzzards: The Odyssey Of The 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team 1943-1945:

“He always carried a six-shot .45 caliber revolver, U.S. Army Model 1917. It had a left-hand holster and Lyman always wore it on the right side with the butt forward, Wild Bill Hickok style … . On the morning after the drop, Lyman was walking in a town with the revolver in hand when a German captain on a bicycle rode around a corner toward him. They were so close to each other that Lyman’s shot knocked the German completely off his seat.”

Several days later, during an attack on an enemy bunker position, Lyman again made good use of his M1917 revolver:

“Lyman stepped out from behind a tree, facing the sentry, certainly no less than forty feet away, and raised his Tommy gun. Apparently, when he pushed the magazine in, he did not slam it hard. When he pulled the trigger, the magazine fell out and the bolt, failing to strip off a cartridge, banged into the chamber with a loud, metallic click.”

“The sentry, hardly more than a boy … stared at Lyman, frozen in disbelief. Lyman threw down the Thompson and drew his .45 revolver. The sentry hardly moved. The .45 slug hit him in the chest … and he went backwards into the bush behind him.”

Shortly afterward, Pvt. Lyman was injured when a backblast from a bazooka knocked him against a tree, fracturing his arm. As related in the above-cited book:

“We heard he took his .45 revolver with him to the hospital. First, they tried to take it away on the grounds it was government issue. He pointed it at a major, telling him there was no way he would let them steal it. Then they sought to use a general anesthetic to set his arm. He refused, saying that they would steal the piece while he was out. So, they told him he would have to have it fixed without the benefit of anesthetic. Lyman said he yelled like hell because of the pain but never gave up the revolver.”

While other American combat troops who used the M1917 revolvers may not have been as passionate as Pvt. Lyman about the sixgun, vintage photos illustrate the guns being employed in combat settings in all theaters of the war.

In May 1945, it was proposed that the M1917 revolvers be declared “Obsolete,” but the provost marshal general objected and the proposal was dropped. This action indicates that the Military Police still considered the revolvers to have value and wanted to retain the guns.

Just before the conclusion of World War II, the Ordnance Dept. contracted with Smith & Wesson and Colt to re-build large numbers of M1917 revolvers. An Ordnance report dated March 30, 1945, indicated that 23,000 S&W M1917 revolvers were overhauled at a cost of $6.80 each, increased to $7.10 on May 12, 1945. The work was to be completed between April and November 1945. A “sandblast/blue” finished was specified. On April 5, 1945, an Ordnance contract was given to Colt for the overhaul of 33,000 M1917 Colt revolvers at a cost of $12 each. The contracts were still in process in 1946.

When U.S. military handguns of World War I and World War II are discussed, most of the emphasis is, understandably, placed on the Model 1911/M1911A1 pistols, as they were the standard military handguns and saw extensive use in both wars. However, the Model 1917 revolvers also saw surprisingly widespread combat use during World War I. Likewise, the M1917 revolvers played an important role in arming Military Police units as training guns and, when necessary, combat arms during World War II.

In many ways, the story of the M1917 revolvers mirrors that of the M1917 rifle. Both were adopted early after America’s entrance into World War I as an expedient measure to provide badly needed arms to the U.S. military at a perilous time. Neither was the first choice of the War Dept., but could be procured much more quickly than the standardized Model 1911 pistol and Model 1903 rifle when time was of the utmost importance.

Both proved to be dependable and serviceable, but were relegated to “second-string” status after the Armistice. Yet when called upon to serve again during World War II, both provided valuable service to our armed forces until the production of M1911A1 pistols and M1 Garand rifles could ramp up to meet the demand.

Although no Colt or S&W Model 1917 revolvers were manufactured after 1919, they proved to be a great investment for Uncle Sam that continued to pay dividends for over a quarter-century. When considering the American handguns of the World War I and II, the Model M1911/M1911A1 pistols are, understandably, given the most attention. However, the valuable contributions of the Model 1917 revolvers to the war effort in 1917-1918 and again in 1941 to 1945 should not be overlooked.