In an effort to piggyback off another’s good fortune, companies will inevitably rush in with similar-looking but inferior products. There’s a thriving black market for fake designer handbags and jewelry that seem like identical copies of their fancier counterparts — at least until they fall apart at the seams or stain your skin green. Your child’s room may have a mimic hiding in plain sight: perhaps a well-meaning relative bought your son a robot “Transmorpher” instead of an honest-to-God Transformer, or maybe your daughter owns a generic “Ice Princess” masquerading as Princess Elsa from the Frozen movies.

We often make the mistake of thinking knockoff goods are a modern problem. In fact, one of the most well-known firearm brands still carries an interesting reminder of a time when its counterfeits saturated the market. On the side of every modern-era Smith and Wesson revolver, you’ll find what collectors call the “four line” rollmark. The first line reads: “Made in U.S.A.” The final two read: “Smith & Wesson” followed by “Springfield, Mass.” But somewhat oddly, the second line is Marcas Registradas. It’s a Spanish phrase translating to “Registered Marks.”

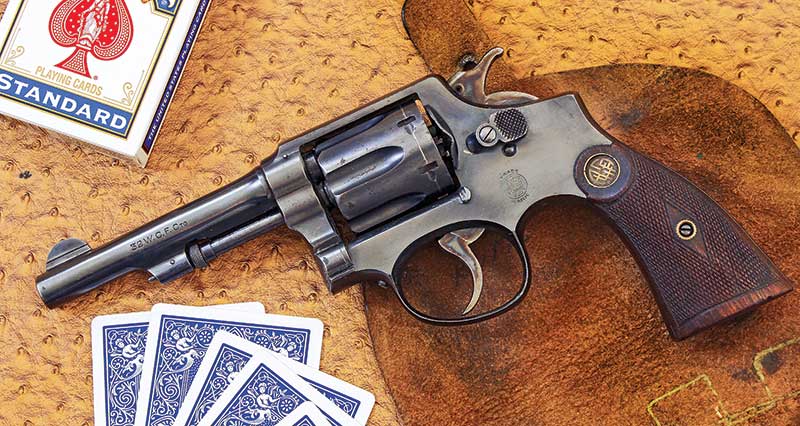

To understand how the line came to be, I call your attention to the “Spanish clones” of the old .38 Hand Ejectors — the parents of the venerable “Model 10” revolver S&W still sells today. My clone, technically known as an Armero Especialistas, “Alfa” model, proves to be an especially fascinating chameleon.

History Lesson

Around the turn of the 20th century, Smith and Wesson’s flagship K-Frame became big news and big business for the Springfield firm. Innumerable Spanish competitors decided they wanted in on the action and began producing a bewildering variety of blatant copies in an effort to meet demand for the awesome guns — and undercut the existing market.

Naturally, S&W found out about this skullduggery and attempted to put a stop to things. While they had some legal success going after American importers on the grounds they were intentionally attempting to defraud consumers, the sovereign nation of Spain essentially told them to pound sand — they didn’t recognize their American trademarks. S&W did eventually secure patents abroad but only after the knock-offs existed on the international market for several decades. S&W added the Marcas Registradas as a way of saying “Stop copying this design!” in a language its counterfeiters would definitely understand but by then, the damage was done.

So what to make of these guns as a whole? First, let’s start with the reality many of the Spanish copies were downright janky. On the low end, there are several design elements that stick out even to the casual observer as being not right at all. It’s common to find design details appearing to be sketched out from memory. Cylinder releases can be of strange teardrop or circular contours, dimensions can look squashed or stretched and often hammers tend to have unusual shapes.

Hilariously, some rollmarks claim the guns are made in “Sprangfeld, Mus.” Others attempt to vaguely match the iconic S&W “Trade Mark” logo with a blobby, sloppily rollmarked forgery. Often, the substandard finishes have worn completely away in the last hundred years and metallurgy is so questionable firing the guns is generally regarded as a bad idea. There are many, many unconvincing fakes.

Some Aren’t Bad

This “Alfa,” however, is a pretty damn successful copy. Every signature contour of the Smith-pattern revolver is mostly intact here down to the smallest of details. The front sight blade, ejector rod, hammer, cylinder release, grip shape, frame dimensions, screw orientation, sight groove and frame detailing are all basically dead ringers for the real thing — it’s almost insidious, really. The barrel appears to be pinned and the quality of walnut stocks are top notch. Even the machining on places like the cylinder ratchet, hand and lockwork is pretty good, and the bluing looks great for being about a century old!

With all this in mind, it helps to remember Spain has a rich history of firearms production stretching back centuries. Consequently, a lot of gunmakers weren’t exactly banging rocks together when they made these guns. There’s clear craftsmanship here — even some “improvements.” For example, many of the Spanish copies used a single beefy V-Spring — not unlike a Colt — in place of three separate springs on the original S&W design. On paper, this made the design slightly less fragile, and in theory, better-suited to military service. The French government went so far as to order many “Spanish Model 92s,” as they were then known, as fighting handguns during World War I.

This robustness, however, has a clear cost. While just about any S&W revolver has a pedigree of being something you can pick up and shoot quite easily, the trigger on this copy flat-out sucks. The double-action mode is easily on par with the worst revolvers I’ve ever shot: the V-Spring stacks for days at the end of an already-stiff travel. But even more impressive in its awfulness is the single-action trigger, which is just as heavy. Mechanically, one spring is both keeping the hammer under tension and pushing the trigger forward, whereas on legitimate S&Ws these are two separate jobs parted out to separate springs.

The effect is a single-action trigger pull in the vicinity of 11 lbs. Yes, 11 lbs. It’s definitely over the 10-lb. limit of two separate trigger gauges I have laying around so the additional pound represents a conservative estimate. I’ll note I can’t attest to mechanical accuracy of the gun: Given my nagging concerns of the metallurgy of any Spanish clone, even one as seemingly well-built as the Alfa, I’ll likely never shoot it. However, given the horrendous trigger, I doubt I’d be fruitful in obtaining any trustworthy data related to how it groups. Also — I have actual Smith and Wessons more deserving of range time.

Pop Quiz

Let me end by asking you this: Had I not told you this was a Spanish clone, would you have been fooled? Admittedly, I overpaid to get the best fake I could.

Some eagle-eyed S&W fanatics would have examined the grip logos and the slight, slight difference in the shape of the trigger guard and immediately suspected something was amiss from your standard five-screw M&P. Would-be sleuths also have the internet now, so it’s easier than ever to pull up side-by-side photo references of a legit gun to compare with the copy.

But say you’re a vaquero in the 1920s who goes into a local gun store looking for one of “those new Smith & Wesson revolvers,” and the guy behind the counter says, “Sure, we have those! And at a cheaper price than you were expecting!” Or, maybe you’re an American shooter who wants one of these nifty double-action revolvers with a swing-out cylinder in .38 special. You know, just like the one you shot at your brother-in-law’s last summer — doesn’t the gun behind the counter look just like what you remember? Long story short, I imagine the tricksters at Armero Especialistas were extremely successful at cutting into Smith & Wesson’s business.

Today, the Spanish copies are little more than a historical curiosity. While I would certainly have no qualms taking a well-worn example of an actual S&W .38 Hand Ejector to the range or conscripting it for self-defense if it were all I had, the Spanish clones are a poor choice for sport or social work. That being said, I think every serious S&W collector should have one or two clones in their collection. They are fantastic conversation pieces, not particularly expensive and hearken back to a profoundly interesting time in the company’s history.