The British Army learned the value of accurate rifle fire the hard way. Pennsylvania Rifle-equipped Americans sniped from the forests and cut down officers from the first fight at Lexington and Concord until the American Revolution ended in 1783. The wars against Revolutionary France demonstrated the need for new tactics, especially after the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. The British Army adopted its first standard rifle in 1800 to meet those demands. The gun’s official designation was the “Infantry Rifle,” but history remembers it as the “Baker Rifle.”

Despite recognizing the rifle’s usefulness, the British Army knew they needed a standardized weapon. An imperial power could not effectively deploy individualized rifles like the Americans and Prussians had. Plus, existing rifles of the time were considered too long, heavy, and generally cumbersome for the skirmishers and light infantry for whom they were intended. The army needed a robust, but easily handled weapon that would stand up to extended campaigning.

Ezekiel Baker’s Rifle…with a Little Help from the Prussians

Ezekiel Baker was a master gunsmith in Whitechapel, London. He submitted a rifle design to the British Board of Ordnance trials in February 1800. Baker’s rifle won the trials, but the design needed work. The first prototype was similar to the standard British infantry musket but was deemed too heavy for its mission.

The army gave Baker a Prussian Jӓger rifle to model what they wanted. Jӓger units were light troops who served as skirmishers and screened heavier infantry formations. They usually carried their own highly accurate hunting rifles in the field, hence the name Jӓger, which means “hunter.” The Jӓger rifles and ammunition were not standardized but the general specifications showed Baker what the army had in mind.

Further Development

Baker’s second prototype was a .75 caliber weapon, the same as the standard “Brown Bess” musket. It had a 32-inch barrel and an eight-groove rifling pattern. The army accepted the prototype, but more changes followed.

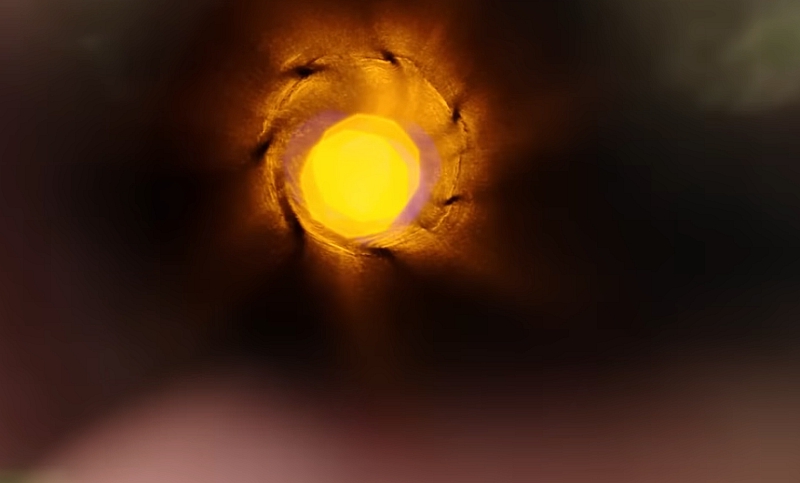

The third and final prototype reduced the caliber to .653 and the barrel was shortened to 30 inches with seven rifling grooves. The rifle fired the .625 caliber carbine bullet paired with a greased patch to engage the rifling. The production Pattern 1800 Infantry Rifle had a .625 caliber bore, firing a .615 caliber projectile with the greased patch. Its effective range was 200 to 300 yards, though it could and did fire much further.

The original Baker Rifle shared the Brown Bess musket’s standard large lock system and swan neck cocking piece. The lock was updated in 1810 to match the new Short Land Pattern Musket. The walnut stock featured a raised cheekpiece on the left side. A scrolled brass trigger guard ensured a firm grip and patches were stored in the buttstock, covered by a hinged brass lid. The Baker accepted a 24-inch sword bayonet.

Specifications

- Caliber: .625 (the Pattern 1809 Infantry Rifle increased the caliber to .75)

- Projectile: .615 caliber lead ball

- Firing System: Flintlock single shot muzzleloader

- Barrel Length: 30.375 inches (the Duke of Cumberland’s Corps of Sharpshooters specially ordered 33-inch models in 1803)

- Overall length: 45.75 inches, 12 inches shorter than the Infantry Musket

- Weight: 9 pounds

- Rifling: 7 grooves

- Standard Rate of Fire: 2 aimed shots per minute

The Baker Rifle’s Service History

The Napoleonic Wars

The year 1800 saw the advent of the Baker Rifle and the “Experimental Corps of Riflemen,” raised, trained, and commanded by Colonel Coote Manningham. Manningham was a veteran of the Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779-1783) and served in the Caribbean during the early French Revolutionary Wars.

As war with Napoleon loomed, Manningham and his Lt. Colonel, William Stewart, took their light infantry lessons from the Caribbean and proposed a new rifle-centered unit to the British Army. The new unit originally provided scouts, sharpshooters, and skirmishers to larger formations. That the Experimental Corps of Riflemen should be equipped with Baker Rifles was only natural.

European line regiments used volley musket fire to make up for their weapons’ inherent lack of accuracy and range. Unlike the smoothbore muskets of the day, the Baker Rifle was extremely accurate, making the soldier more effective at a longer range. Rifles were also more difficult and expensive to manufacture, limiting their use to specialists like the Experimental Rifle Corps.

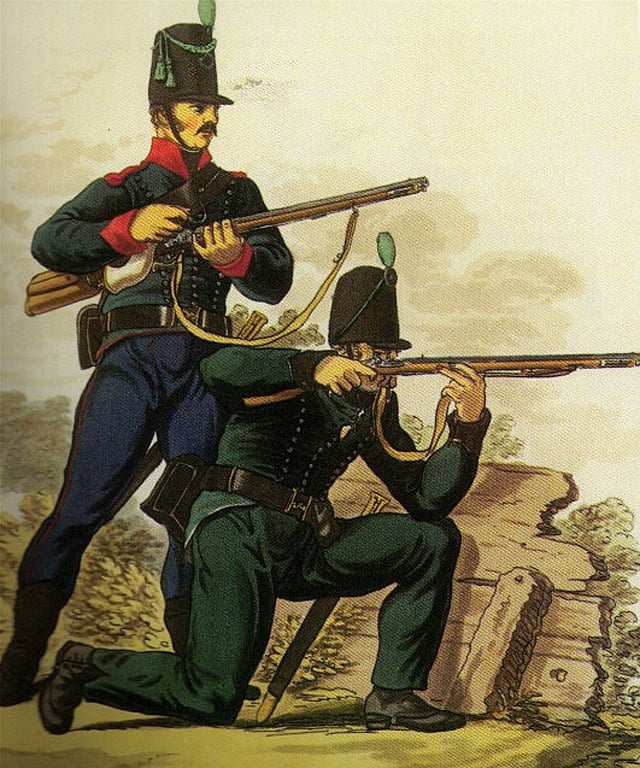

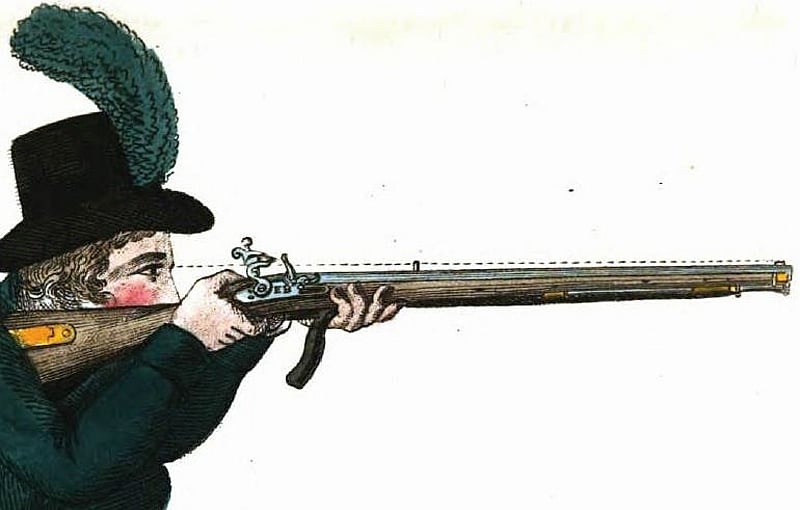

Befitting their mission, the riflemen wore dark green uniforms with black facings instead of the standard red coat with white trim. They wore black belts and had green plumes on their tall shako hats.

The Rifle Corps saw its first action on 25 August 1800, spearheading a British amphibious landing at Ferrol, Spain. The landing eventually failed, but the riflemen distinguished themselves by helping clear Spanish defenders from the high ground overlooking the beach. A company of riflemen used their Bakers as shipboard sharpshooters at the Battle of Copenhagen the following April.

The 95th Regiment of Foot

The Rifle Corps officially joined the British Army as the 95th Regiment of Foot in 1802. Their Baker Rifles went with them. The 95th served all over the world, from Germany to South America to Denmark. It was in Denmark that the 95th first served under Brigadier Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington.

August of 1808 saw the 95th dispatched to Portugal under Wellesley. The riflemen fired the opening shots of the Peninsular War against Napoleon in a skirmish at Óbidos on 15 August. Two days later, the 95th participated in the war’s first pitched battle at Roliça.

The Baker Rifle’s Most Famous Shot

Rifleman Thomas Plunkett made the Baker Rifle’s most celebrated shot at the Battle of Cacabelos on 3 January 1809. The 95th formed part of the rear guard for Sir John Moore’s retreat to La Coruña, Spain. Hard pressed by French General Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais, the rear guard defended a stone bridge over the Cua River with the 28th Foot, 52nd Foot, and six guns of the Royal Horse Artillery.

As the French rushed the bridge, Plunkett rushed onto the span, lay on his back, and rested his Baker on his crossed feet with the stock under his right arm. Plunkett aimed his rifle at General Colbert, leading the charge on a distinctive grey horse, and dropped him with one shot. Then, to prove it wasn’t a fluke, he killed the staff officer who rushed to the general’s aid. The French retreated in confusion. Plunkett then ran back to the British lines.

Many sources cite the range of Plunkett’s shot as 600 yards. The best that historians and battlefield investigators can estimate is somewhere between 200 and 600 meters. A remarkable feat either way. Plunkett had served with the 95th since at least 1807. He continued throughout the Peninsula Campaign and later in the Hundred Days Campaign that ended at Waterloo in 1815.

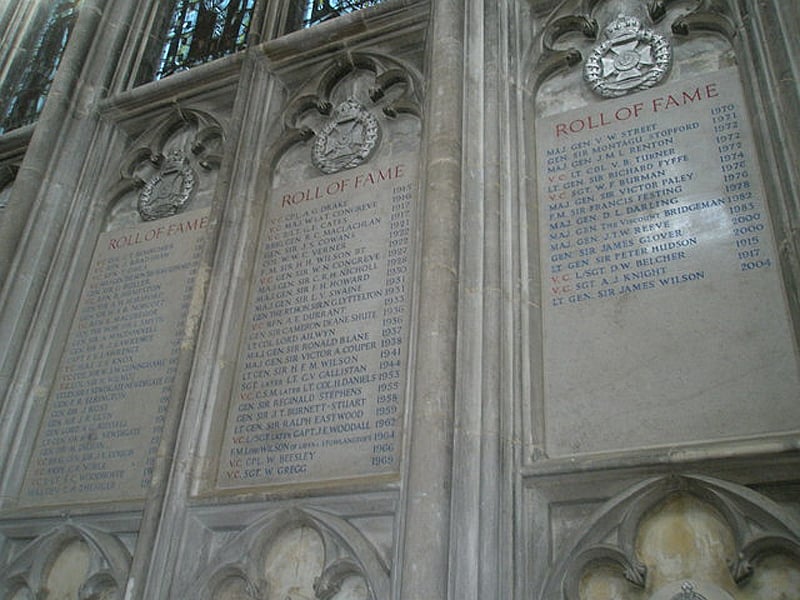

A Distinguished History

The 95th Regiment served with distinction until Napoleon’s defeat. They also saw action in Canada and the 1814 Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. Their distinguished record ensured their survival when the British Army downsized in 1816. They were redesignated as the “Rifle Brigade” on 23 February of that year. Wellesley, the victor at Waterloo and now the Duke of Wellington, served as the unit’s Colonel-in-Chief from 1820 until his death in 1852. The Rifle Brigade is one of the British Army’s most celebrated regiments to this day.

The Baker Rifle Around the World

The 95th Regiment of Foot was the most famous unit to deploy the Baker, but the rifle also saw good use by the elite 60th Regiment of Foot and the King’s German Legion included sharpshooter platoons in each of its line battalions. The 10th Hussars used a cavalry variant of the Baker Rifle. The British also supplied Bakers to their Portuguese, Austrian, and Russian allies against Napoleon. American forces reportedly used captured Bakers in the War of 1812.

British forces deployed the Baker in Canada in the War of 1812 and Santa Anna’s Mexican army used them at the Alamo in 1836. Baker Rifles were even supplied to Nepal, some of which were released from storage in 2004, though they were so badly deteriorated that most could not be saved.

The British produced Baker Rifles until 1838 and issued them until 1841. The rifle’s official 42-year service life attests to its quality and effectiveness.

Shooting the Baker Rifle

As with other muzzleloaders, the Baker Rifle had a precise loading drill. It consisted of seven distinct steps that were learned by command. Loading on command is more appropriate for line units than skirmishers, but the Baker did serve in line regiments.

Once loading was complete, the rifleman responded to the commands “Company,” “Ready,” and “Present.” “Present” told the rifleman to bring the weapon to his shoulder, acquire his target, and fire as soon as he was ready. Rifles were more accurate than muskets, so aimed fire, instead of volley fire on command, was more effective. This drill only applied to the standing position.

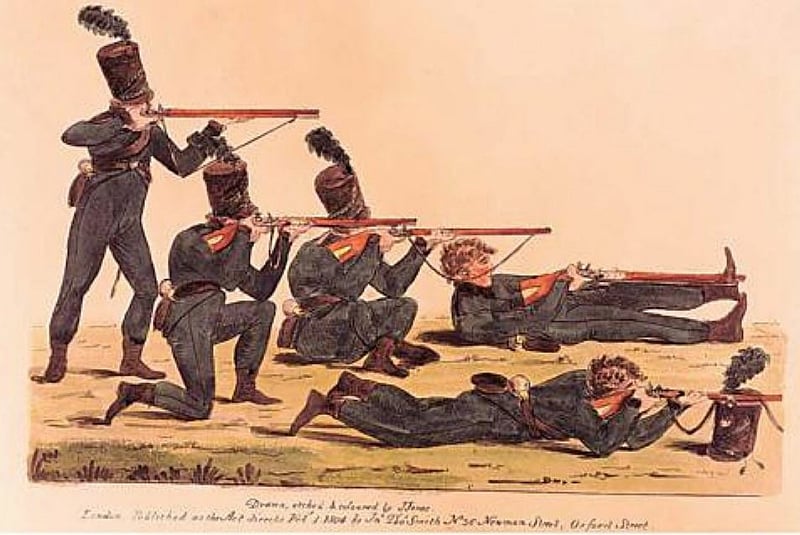

Firing Positions

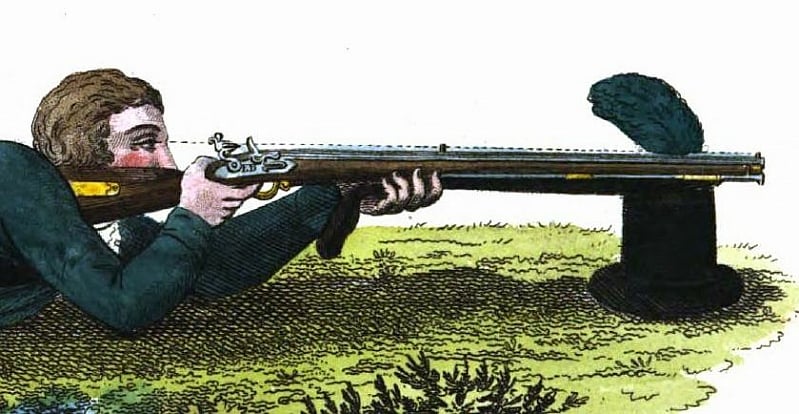

Skirmishers’ and sharpshooters’ firing positions were more varied, so they operated as the situation demanded. There were at least five different “approved” firing positions for the British riflemen: standing, kneeling, sitting, prone, and lying on one’s back. This last position saw the rifleman use his ankle or foot, often crossed over the other, as a shooting rest. The riflemen often rested their weapons on their shako hats in the prone.

Thanks to the greased patch, which necessarily fitted tight in the barrel, the Baker Rifle loaded slower than the musket. The standard Baker rate of fire was two aimed shots per minute, whereas the musket’s rate could be as high as four. Experienced riflemen could reportedly fire three rounds per minute under ideal conditions. The nature of skirmishing and sniping often led to a much slower fire rate since it often depended on stealth and targets of opportunity.

Riflemen were known to not use the patch in hot situations, preferring faster reloads to precise marksmanship. They used standard paper cartridges instead. This was probably more prevalent in the line units than the skirmishers or sharpshooters, but riflemen could use their normal projectiles without the patch in emergencies, though accuracy suffered considerably.

The Baker Rifle’s Legacy

The Baker Rifle was maybe the finest of its type for nearly forty years. Ezekiel Baker himself made 712 Baker Rifles. He subcontracted the other 22,000 or so to over 20 other gunsmiths and shops. The production process often had different contractors make different parts, with the final product assembled at the end.

The Baker’s concurrence with Manningham’s Experimental Rifle Corps combined to give the British Army not only a new weapon system, but the troops and doctrine to use it effectively. The British Army began experimenting with percussion caps in 1834, finally adopting percussion rifles and muskets in 1842. Percussion caps were far more efficient than flintlocks, and so better technology overtook the Baker.

Still, the Baker Rifle is a classic military firearm that served the world over, nowhere more prominently than in the gargantuan wars against Napoleon. In the age of musketry, the Baker Rifle was a force on the small arms battlefield.

Few period Baker Rifles survive today. They saw hard service and the British made no real effort to preserve them. There are reproductions available but make sure you do your homework on the companies producing them. It looks like parts kits are perhaps the best route, assuming you have that kind of skill and the tools needed for the job. If you like that sort of thing, maybe pick one up and experience a little history.