When Nazi Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, they found the Polish military to be inferior in numbers, but not completely short-changed in effective equipment or fighting spirit. Several Polish weapons systems were quite effective, as the invading Nazi and Soviet troops were soon to find out. Some of the Polish infantry weapons may appear quite familiar to American small arms enthusiasts.

The Ckm wz. 30 Heavy Machine Gun

From 1919 until well into the 1920s, Poland’s military used a large amount of older, heavy machine guns that they either inherited, purchased from their allies, or captured in some numbers from their enemies (in this case Imperial Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and shortly after World War I the Soviet Union). The mix of French M1914 Hotchkiss guns (8 mm French), Russian Maxim M1910 guns (7.62×54 mm R), German MG08 (7.92×57 mm) and Austrian Schwarzlose M.7 (in a wide range of calibers) proved to be a logistical nightmare that the Poles sought to redress.

The business end of the Polish wz. 30 heavy machine gun.

After a series of tests and competitions that concluded during 1928, the Poles were thoroughly sold on the capabilities of the Browning M1917 machine gun, rechambered to 7.92×57 mm. Polish officials had settled on the Colt-manufactured M1928, a commercially manufactured export version of the famous Browning machine gun, and opted to purchase a license to manufacture. The price for the license proved to be prohibitive ($450,000) and Colt also demanded to make the first 3,000 examples in their own factory. The Poles were forced to find alternatives, when a thunderbolt of good luck struck in Warsaw—Colt had never secured a patent of their machine gun in Poland. After discovering the opportunity, the Polish armaments ministry began to manufacture the weapons in Warsaw. By 1931, the first Ckm wz. 30 machine guns were issued to Polish troops.

Polish Home Army resistance fighters prepare a wz. 30 machine gun for action during the Warsaw Uprising in the late summer of 1944.

The Polish variant is recognizable by its longer barrel (28” compared to 24” on the American original) and by a significantly longer flash suppressor. Several tripod mounts were developed for the Ckm wz. 30, all capable of transitioning to the anti-aircraft role with a mast extension (and special AA sights). A shoulder-stock extension was also available. The Ckm wz. 30’s cyclic rate (600 rounds per minute) was equivalent to the US M1917A1. All told, almost 9,000 were made for Polish forces by the time of the German invasion.

Wz. 30 machine guns reviewed by Polish Marshal E. Rydz-Śmigły. (Courtesy Polish National Archives)

The Polski-Brownings were used both before and after Poland fell in September 1939. About 1,700 Ckm wz. 30s were made for Republican Spain and were in action during the Spanish Civil War. The Germans captured many Ckm wz. 30s and used them as the “7.9 mm sMG 30(p)” in second-line and fortress units. The Polish resistance hid a few of the Ckm wz. 30s during the German occupation, and these emerged during the Warsaw Uprising by the Polish Home Army during August of 1944.

After the end of the Battle of Westerplatte, German troops review captured Polish equipment, including the wz. 30 heavy machine gun. Note the special AA sight in the hand of the German soldier in the center.

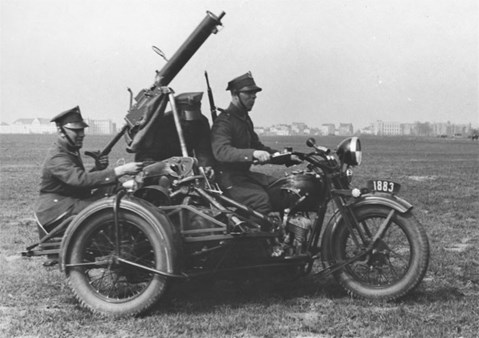

Wz. 30 set up for AA use aboard a Polish Sokół 1000 motorcycle combination. (Courtesy Polish National Archives)

The Browning wz. 1928 Automatic Rifle

As Poland developed its small army during the 1920s, they paid careful attention to the latest trends in small arms design. The Poles became interested in the new concept of a “squad automatic” and turned their attention to new concepts from western Europe. They ultimately settled on what is now considered a classic American design. After an extensive search and a 1925 arms competition, the Poles chose the Browning Automatic Rifle—in this case a Fabrique Nationale variant made in Belgium. Ultimately this became the “7,92 mm rkm Browning wz. 1928”, chambered in 7.92×57 mm Mauser and first commissioned in 1927.

The Polish BAR: Polish troops with a wz. 1928 automatic rifle (7.92×57 mm). (Courtesy Steve Zaloga)

The first 10,000 examples of the wz. 1928 were made in Belgium at FN. Subsequently, Poland also bought a license to build the Browning automatic in their own country (production in Poland began in 1930). The new wz. 1928 featured a few modifications compared to the US M1918 BAR: a longer barrel fitted with cooling fins, a folding bipod and simplified sights. Some wz.1928s were also equipped with a carrying handle and a “fish-tail” buttstock. About 14,000 were delivered to Polish infantry and cavalry units before the invasion of September 1939.

The wz. 28 in action: Note the enlarged forward grip and the bipod.

By all accounts, the Polish wz. 1928 was a well-made and highly effective weapon, offering all the benefits of the widely celebrated BAR. The wz. 28’s greatest drawback was its lack of extended-fire capability, limited by its use of 20-round magazines. The Poles had planned on producing an extensive number of spare barrels, but the program was interrupted by the invasion. The Germans captured a large amount of wz. 28s, and happily used them in their service throughout the war as the “lMG 28 (p)”.

After Poland fell, Germany acquired a windfall of captured small arms. Here a wz. 28 sits atop a pile of Polish Mauser rifles.

The 7.92 mm Kb. Ppanc. wz. 35 Anti-Tank Rifle

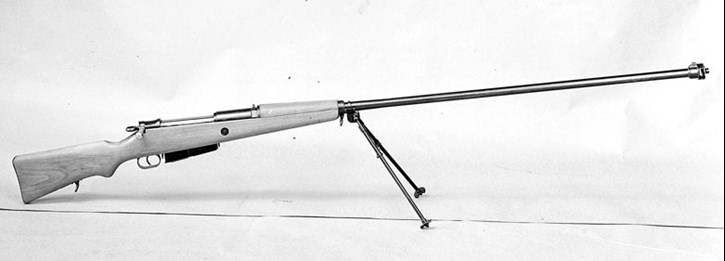

While Germany prepared for the blitzkrieg, the Poles were doing what they could to defend themselves against an attack they felt was inevitably going to come. Poland could afford few armored vehicles, but they did invest in some effective anti-tank weapons. One of the weapons they developed in secrecy was a high-velocity anti-tank rifle: the 7.92 mm Kb. Ppanc. wz. 35. Patterned after the standard Mauser rifle, the wz. 35 featured an exceptionally long barrel (47 inches, creating a rifle that was 69 inches long overall). A special harness was produced to allow the anti-tank rifleman to carry it on his back.

The unique Polish wz. 35 anti-tank rifle. Chambered for the 7.92×107 mm DS round, the wz. 35’s muzzle brake was particularly effective, reducing the recoil to little more than that of a standard Mauser rifle. (Courtesy SA-Kuva)

A great deal of effort was put into creating the wz. 35’s ammunition: the 225-gr. 7.92×107 mm DS round. The small 8 mm round relied more on kinetic energy than it did traditional armor penetration. Instead of punching a tiny hole through the armor of an enemy vehicle, the DS round transferred incredible kinetic energy to the armor plate, which normally resulted in “spalling” on the inside of the armor. The impact of the DS round on the armor would break off about a 20 mm plug from the interior surface of the vehicle, sending a molten-hot metal scab ricocheting at killing speed inside the enemy tank. The intention was to kill or wound the crew and set fire to fuel or ammunition. Ultimately the wz. 35’s ammunition was effective out to 300 meters on lightly armored vehicles and was capable of penetrating 33 mm of armor plate at 100 meters.

After Poland fell, the Germans sold some of their captured wz. 35 AT rifles to Finland. This example is seen during training exercises with Finnish troops in the summer of 1942. (Courtesy SA-Kuva)

Initial muzzle velocity was 4,180 f.p.s. Unfortunately, the barrels wore out quickly, often after just 200 rounds. Three spare barrels were issued with each wz. 35 to help with this problem. The Polish design team conquered the powerful recoil of their anti-tank rifle with a highly effective muzzle brake (said to have bled off 65 percent of the additional recoil energy). With the muzzle brake in place, anti-tank riflemen reported that the felt recoil of the wz. 35 was little more than the standard Mauser rifle.

Many of the German tanks and armored cars that were deployed during 1939 were light vehicles with very thin armor. Consequently, the Panzer I (two-man crew) and Panzer II (three-man crew) were vulnerable from the front to fire from the wz. 35. Larger German tanks, like the Panzer III and Panzer IV carried frontal armor that was able to handle hits from the wz. 35 except at very short range. One of the drawbacks of such a small caliber anti-tank weapon quickly manifested itself, as while the wz. 35 proved capable of killing or incapacitating the crews of the German light tanks and armored cars, the DS rounds generally did not destroy the vehicles themselves. A curious by-product of this phenomenon were the so-called “ghost tanks” that the Germans recovered from the battlefield; vehicles that had been temporarily stopped with dead crews, but were quickly re-manned and put back into service.

Germany retained a number of the captured Polish AT rifles, using some of them during the invasion of France in 1940. This example is examined by U.S. troops in Germany during the spring of 1945.

About 6,000 of the new AT rifles were delivered by the beginning of the war, but since they were developed in secret, most Polish troops had no experience in firing them, nor did they have any tactical guide to use them. The wz. 35 is often known as the “UR,” short for Uruguay, which was a cover name/destination the Poles applied to their AT rifles. They certainly caught the attention of Poland’s enemies—the Germans captured many and put them to work in their service during the subsequent invasion of France as the “7.92 mm Panzerbuchse 35 (p)”. Soviet agents scoured eastern Poland for the “secret rifles,” and captured examples of the wz.35 were used as inspiration for their later PTRD and PTRS anti-tank rifle designs.

Additional Reading:

Uprising! Poland’s Fight for Freedom in Warsaw 1944